Through Rupture and Belonging: Interview with Nermine El Ansari

Through Rupture and Belonging: Interview with Nermine El Ansari

The body carries memories; we remember things that seem unconnected but are associated through the reminiscence of something distantly familiar. Social geography, collective, and personal memory are the keywords to approaching Nermine El Ansari’s art practice. She explores how we connect to places through the memories we carry within our bodies (or mental spaces) through drawing, print, video art, installations, and performances.

El Ansari (b. 1975) is a French-born Egyptian visual artist who has lived and worked in Reykjavík, Iceland, for eight years. During that time, she has become an integral part of the community of artists working and living in Iceland by being a board member of the Living Art Museum, participating in Komd’inn, a public programming initiative at Gerðarsafn, Kópavogur and teaching at the LungA Art School, Myndlistarskólinn. Currently, she is doing a residency at Skaftfell Art Center, Seyðisfjörður, where she will focus on the idea of displacement.

I spoke to Nermine El Ansari about her current residency, practice, recent works, engagement with cultural institutions, and public programming.

I want to start by discussing your intentions, hopes, and dreams during the Skaftfell residency. What are you planning on working on?

My project explores ways to give new forms of visual expression to ideas of displacement and exile, to seek a deeper understanding of isolation and the eternal search for a place to truly belong. The project is inspired by my personal experiences going through multiple relocations since childhood. Inspiration is also drawn from those asylum seekers who sought refuge in Iceland, whose stories I have been able to bear witness to since 2015 as an interpreter (from Arabic, Spanish to English) at the LGBTQ organisation in Reykjavik and the government immigration office. The asylum seekers’ stories echo through my work: the intense rupture brought about by separating from one’s homeland and the memories—set against a new, unfamiliar land. In creating an imaginary scenery crossing geographical and emotional borders, I aim to cultivate understanding and empathy, reminding us that belonging is a shared human quest. The project will be undertaken in a six-week residency at Skaftfell Art Center in Seyðisfjörður from October 15-November 30 and culminate in an exhibition in the Skaftfell Gallery.

In your work, you often deal with topics of memory. Why did you start being interested in memory? Has it always been the concept you work on within your visual art?

To answer this question, I have to be personal, go back to memory, and analyse my situation. At one point in my career, I shifted my focus from working with the body and its distorted human and animal forms to social geography and memory. I grew up in a multicultural environment between Paris, where I was born, and Cairo, where my parents are from. I constantly travelled between these two cities from a very young age. At 19, after completing my first year at the Fine Arts School of Cairo, I left to study art in Paris, where I stayed for eight years.

During this period, I started using the body as the main subject in my work. My interest in body arose during the live model and morphology classes we had in the fine arts in France. Coming from Fine Arts of Cairo, a very conservative school in which the models we drew were fully covered, I found myself in a classroom with many different nude models changing position every few minutes for three hours. The change in methods was already fascinating, a radical change.

Arab culture is very bashful about the female and male body, to the point where the body becomes this invisible presence that wanders from place to place. I grew up in two very different cultures (Egyptian and French) in their tradition, religion, and beliefs, where the thoughts and forms of education are sometimes almost in total opposition. As a child, I had to combine them and adapt to my environment. I call this phenomenon the journey of the distorted body. In this case, examining the human form was an integral part of the concept of identity that I circumvented by studies of the body in its most human state up to the bestiary.

On my return to Cairo in 2002, much geopolitical upheaval took place in the Middle East following the attacks of September 11 (the collapse of the World Trade Center). When the 2003 invasion of Iraq turned into the Iraq war for almost a decade and ‘the Arab spring’, a series of revolutions spread across much of the Arab countries, including Egypt, back in Cairo felt like being in an explosive city (region) with the very bad and very good all together maybe like the weather in Iceland when it gets extreme with the storm hail snow rain. You can hardly walk in the street, and your face hurts because of the hail mixed with the storm that whips the skin of your face. It’s the intense moment where all kinds of emotions come between love and hate. The environment or social geography slowly replaced the human and bestial physicality as an object of study for identity.

Memory is an imprint of something that no longer exists in its physical form but remains in people’s minds and is inherited from person to person, making it last over time, from past to present to future. I’m intrigued by its time duration and ability to shape the future of spaces, locations, regions, and individuals.

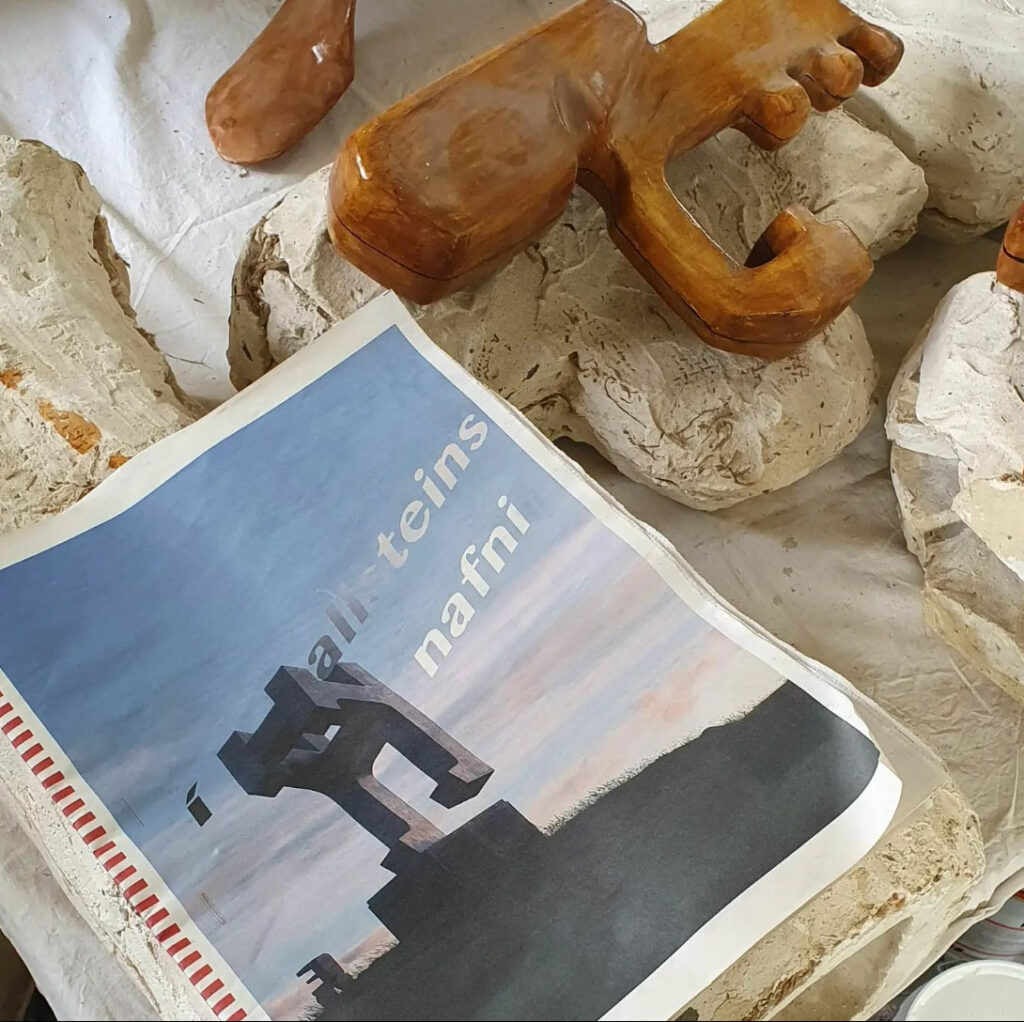

In your most recent work, Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image (2020), memory plays an integral role. Can you tell me more about how that work came to be?

Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, is a performance that results from a long work process. The starting point was while I lived in Cairo during a curfew period set up by the army following the Rabaa massacre in August 2013. I started making a series of drawings in which I had to remember a specific childhood memory before age ten and try to redraw it as I saw it in my mind.

In 2014, I applied to an art residency in Iceland (SIM) to meet other artists in different contexts and to ask them to do the same exercise. It was an excellent introduction to Icelandic culture because you go directly deep into culture when you speak with people about their childhood memories.

Later, I asked many artists from Egypt and other countries to do the same and to meet to discuss the images we made, not to mention the memories. As we discussed the images, I was taking notes on what we were saying about each. Afterwards, I wrote a short text for each image inspired by our discussions. Then, I concentrated again on the series I made on A4 paper and decided to redraw them on much larger formats. During this process, I no longer thought of the memory but only of reproducing the small drawing on a larger scale. As a result, some of these drawings have been reproduced three or four times and have yet to be identical. Lastly, I created a narration between these drawings and images found on Google by associating them. This work was first presented as a solo exhibition at SIM Gallery in 2018 under the title Memory Spring, co-curated by Erin Honeycutt.

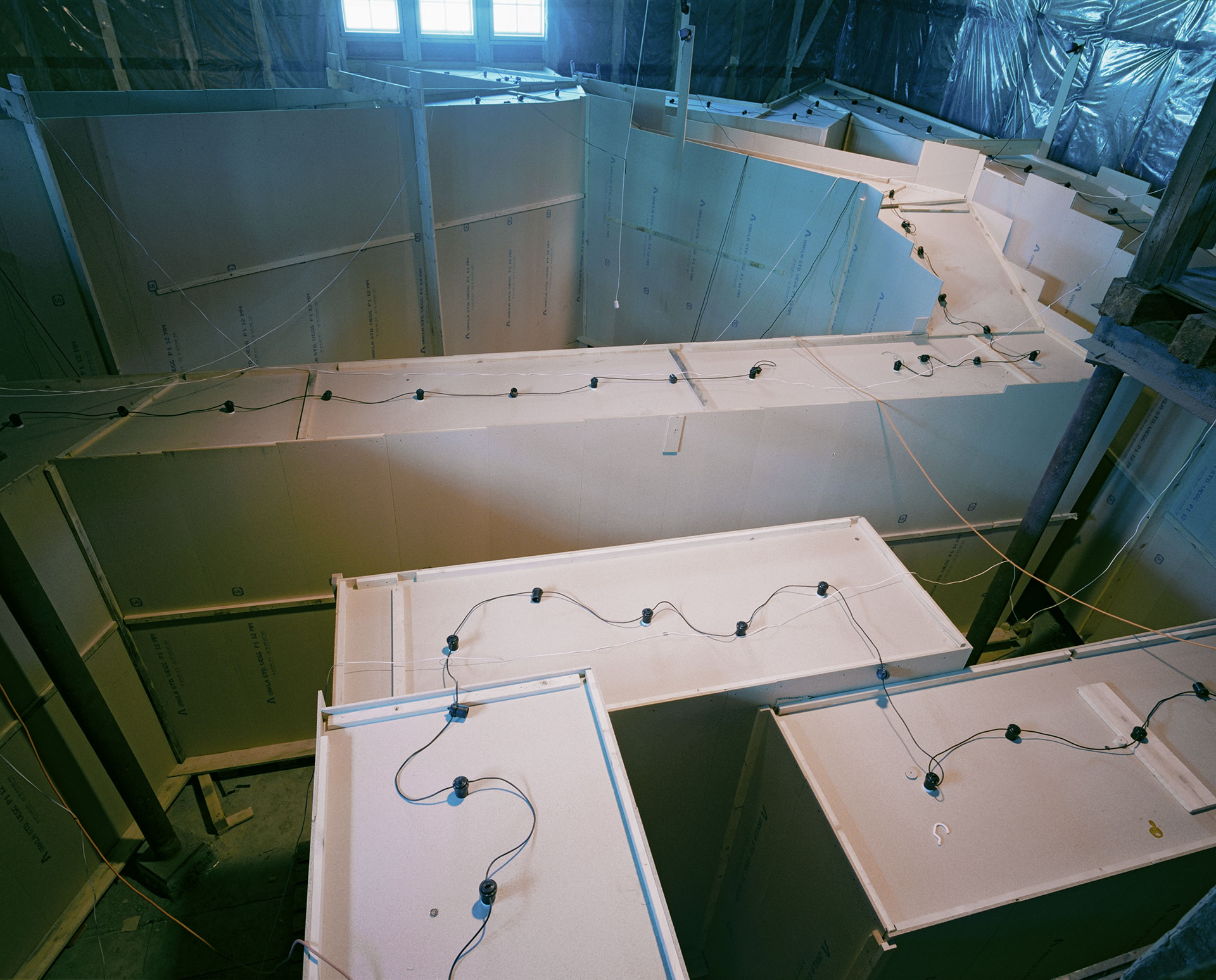

In 2020, I was commissioned to present a performance at the Mucem, Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilisations auditorium in Marseille (France). I transformed this work into a visual and auditory performance. I collaborated with Adam Switala, musician, composer, and researcher, and Piotr Pawlus, filmmaker and photographer. I first collected the drawings depicting memories, then the photos and documents from Google. I created new associations of images for storytelling that were aimed to be projected on two screens of different formats. Then, I reworked the texts for the auditory, sound, and performance parts. Unfortunately, this work was only broadcast via video streaming due to the lockdown restrictions (COVID period), which resumed during the last week of rehearsal at the museum auditorium. The audience consisted only of people working in the museum.

I would love to show it here in Iceland and have the artists who collaborated be a part of the performance; that would be a big dream. It would be performed in English, but it may also be nice to have Arabic and Icelandic since I worked with Icelandic and Egyptian artists and played with the languages.

The concept of identity is powerful within this work and is a theme that runs through most of my work. I like to question the idea of individual and national identities, for example, why there are so many physical and cultural borders between people and countries. When you return to the origin of childhood memories, you realise how many similarities we have.

Identity also played a significant role in your event with Komd’inn where you interviewed and interpreted Sara Mia about her experience of moving to Iceland.

When Helena, one of the programmers of Komd’inn, told me about Habibi Collective, a collection of movies from the Middle East collected by Róisín Tapponi, which were mainly made by women, I got very interested. Tapponi is a young Iraqi-Irish researcher living in London, we thought it would be exciting to show a movie from Habibi Collective in Gerðarsafn and organise an event.

Spontaneously, I thought of selecting a movie about transgender in the Middle East, and I thought about a very good friend of mine, Sara Mia, who is the first transgender person from the Middle East who has been received by Iceland. She didn’t come as a refugee. We met in Iceland when I arrived in 2015. She is the first foreigner transgender person in Iceland to go through the process of changing her gender and national identity, and she gained Icelandic citizenship after three years. Changing gender identity was also new in Iceland for Icelanders in 2014; the laws were finalised in 2019.

I work as an interpreter for Samtökin 78, one of my first jobs in Iceland, incidentally. I have worked there since 2015, mainly interpreting for Arab queer people seeking asylum in Iceland. I first worked with Sara, who arrived in Iceland in 2014. When Samtökin 78 reached out to me, I had only been in Iceland for a few months when they asked me whether I was willing to be an interpreter for her with a social worker.

Before the meeting with the social worker and Sara, I was taking Icelandic courses at the Tincan Factory school, and in the class, I found myself with Sara, but we didn’t know each other. Slowly, during the break, we started to find out that I would be her interpreter. The first time we met was a very special and serendipitous moment. In the coming months, we met a lot in Samtökin, doing many sessions, which was a deep and serious period, working with her and the social worker while she was in the process of changing her gender and identity, applying for Icelandic citizenship. We became close friends throughout the process, which was an intense experience. It wasn’t the first time I got to know someone who was transgender, but it was the first time that I got to hear and learn about the experience in such a profound way.

When Habibi Collective suggested that we would show a 90s documentary Cinema Fouad from Mohamed Soueid, about a transgender person living in Lebanon, it matched so well to have a conversation with Sara. She is very involved in the queer community, and she directly made the connection with Lebanon because she goes back there a lot and speaks openly about it. However, Sara is very far from the art scene and didn’t immediately feel comfortable speaking in a museum, but after watching the movie together, she found many similarities to her experience and became more convinced and enthusiastic about the event. Not only because transgender is an issue in the Middle East, but the whole discussion is still taboo in Iceland as well. We decided not to talk only about her experience but about the film and the conflations with her experience.

Our talk was in Arabic, but I was simultaneously interpreting it into English for the audience since telling one’s story is always more comfortable and better in one’s native language. Moreover, there aren’t enough events around the arts in Iceland that present or discuss other cultures or are programmed in languages other than English or Icelandic. It’s not because there aren’t people from Asia or the Middle East here; there are other reasons. Sara and I were both pleased with the event, which went very well. I hope more experimental events like this will take place in the future because they give platforms to people like Sara who have meaningful experiences to share.

From Komd’inn event with Sara Mia, 2022

From Komd’inn event with Sara Mia, 2022

From Komd’inn event with Sara Mia, 2022

From Komd’inn event with Sara Mia, 2022

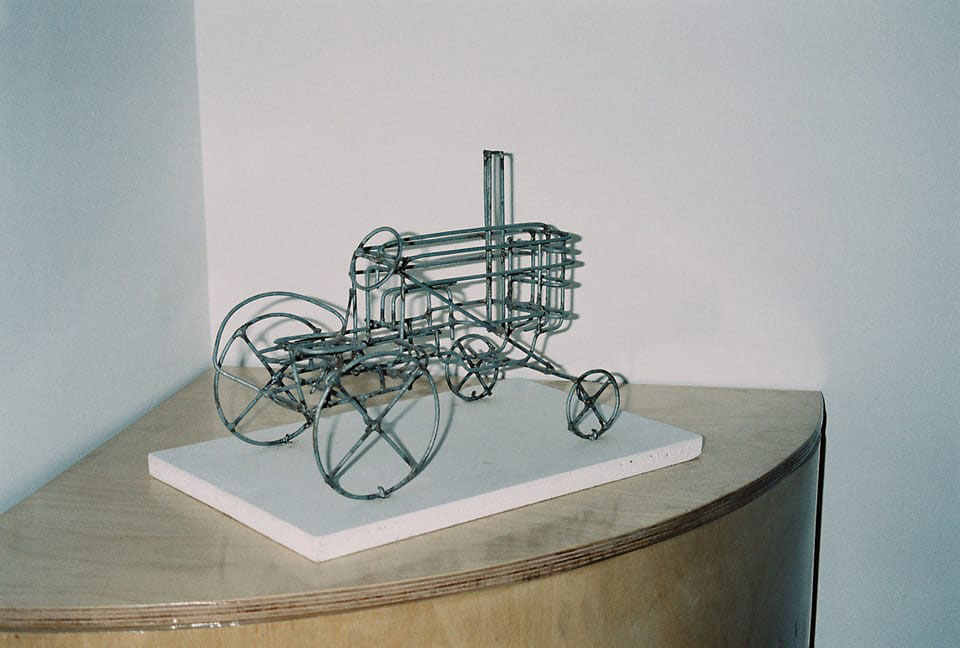

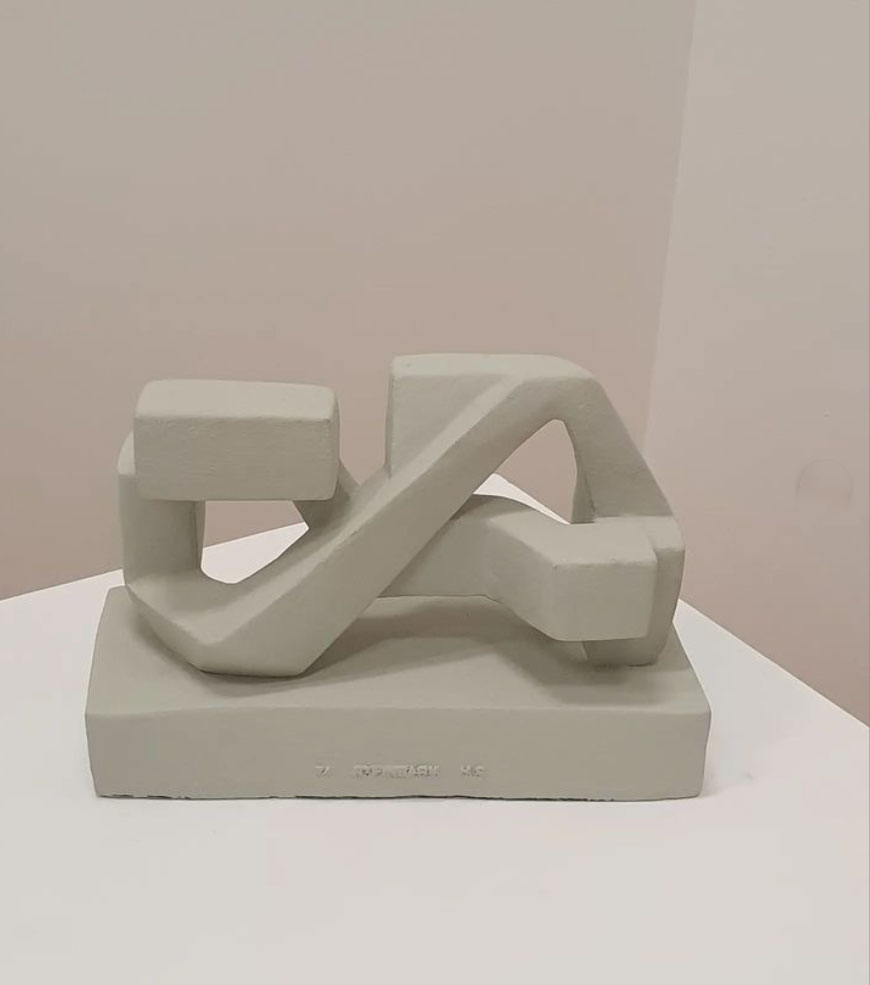

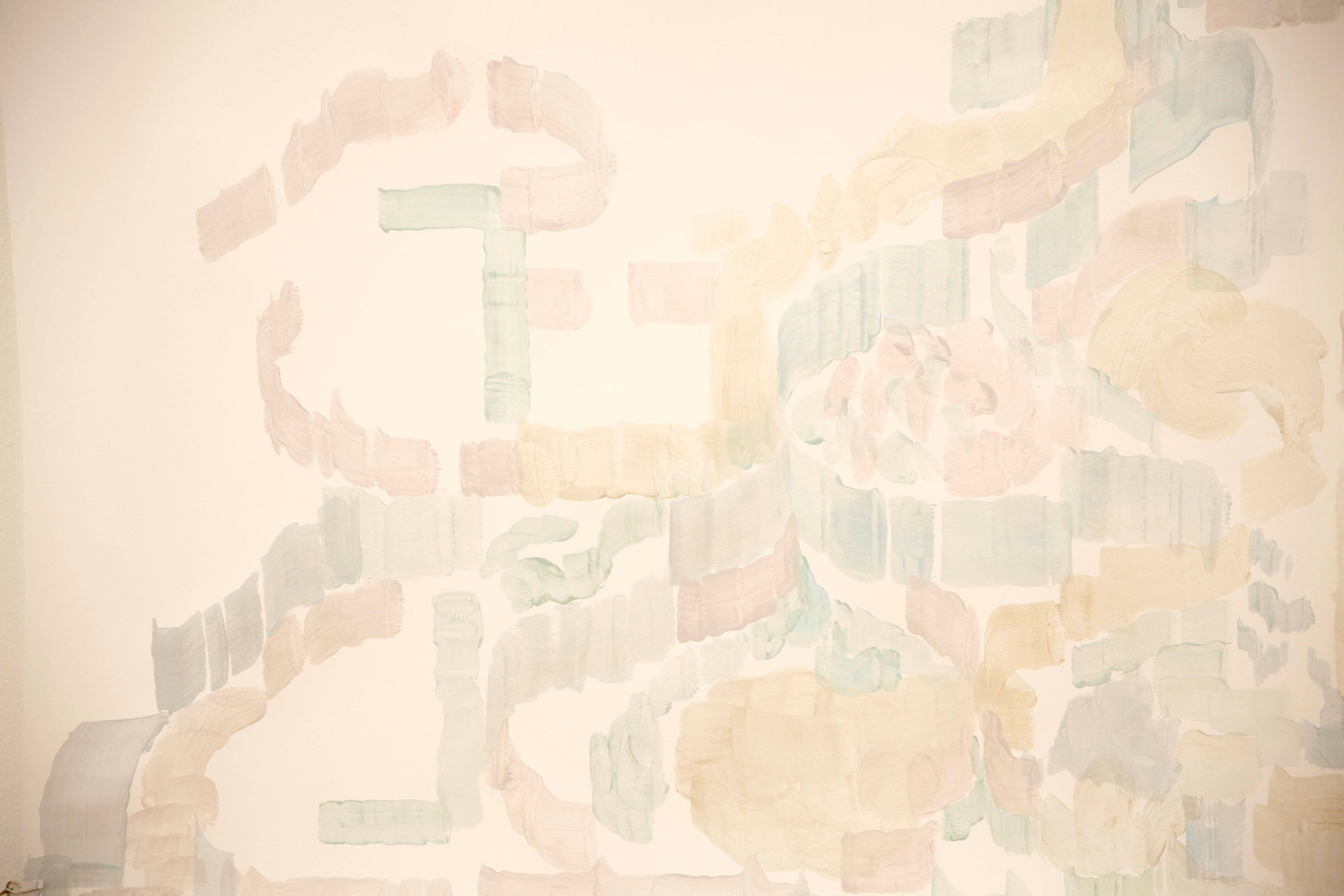

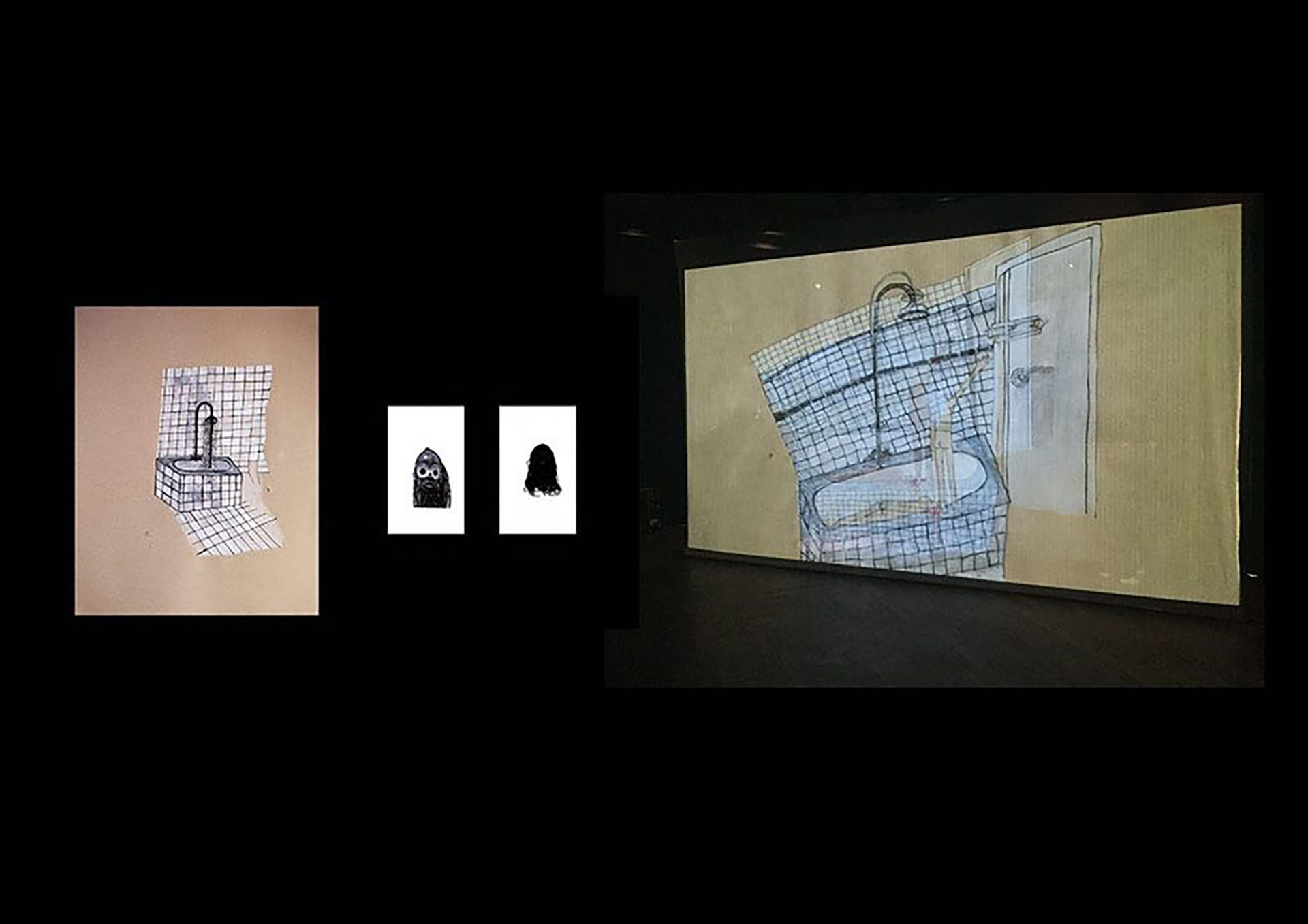

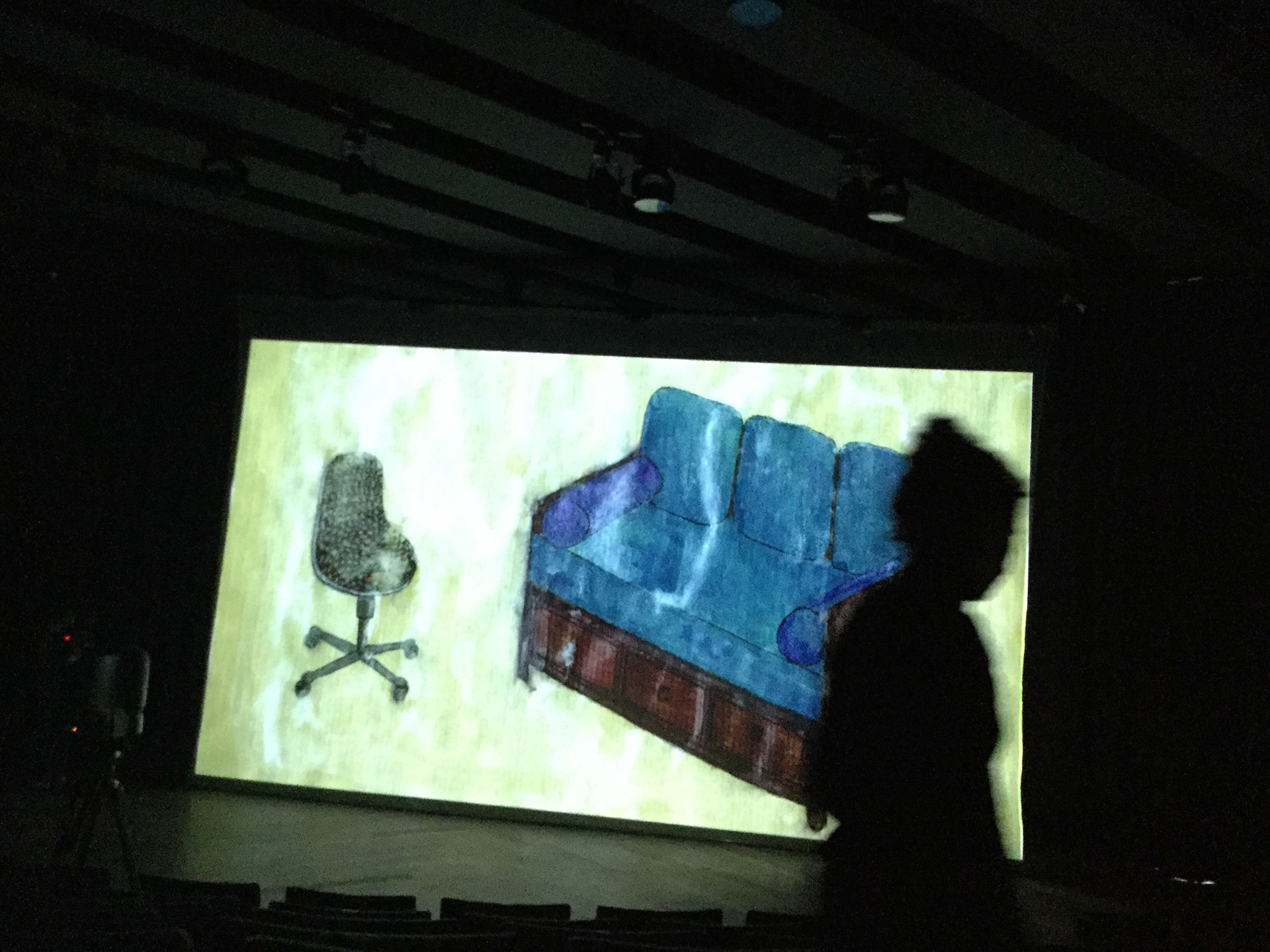

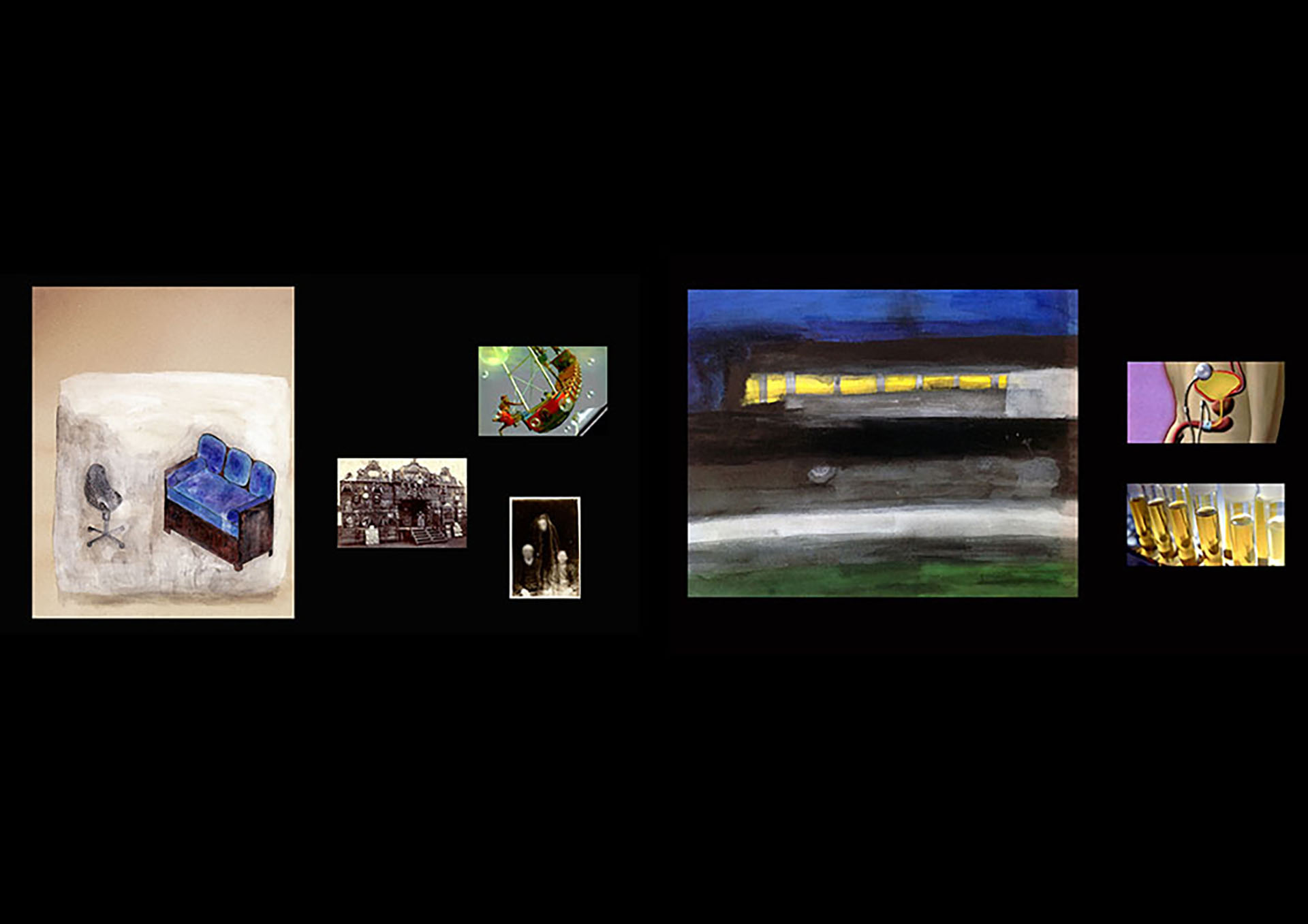

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

Eva Lín Vilhjálmsdóttir

Photos from Komd’inn by Vikram Pradhan.

Photos from Nermine El Ansari’s performance, courtesy of the artist.

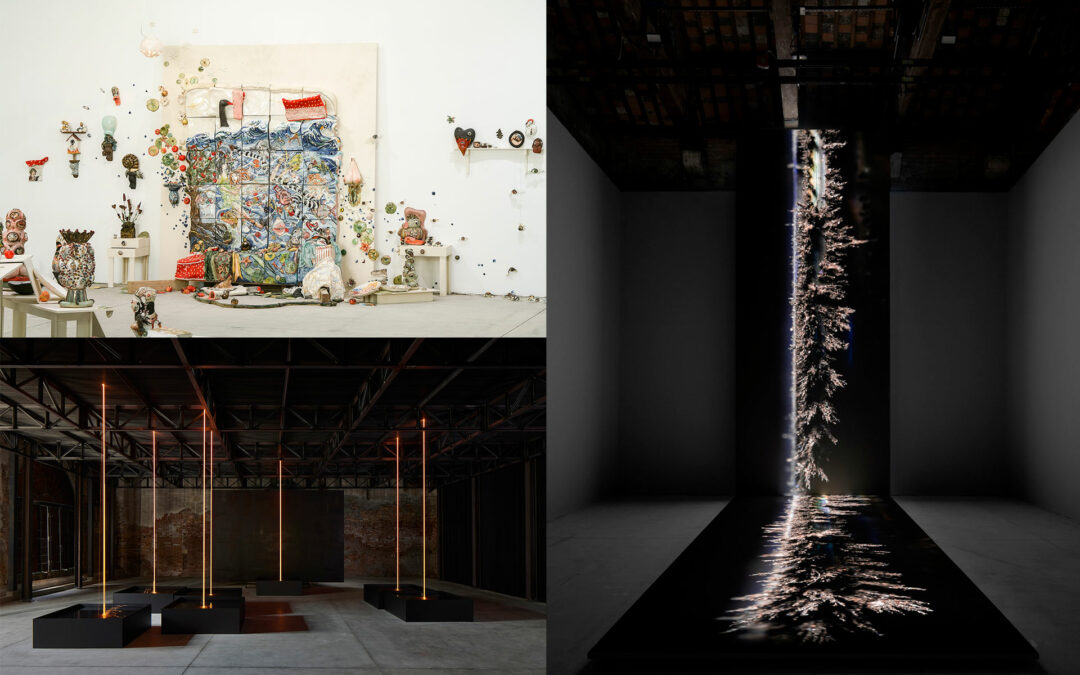

Photographer: Aleksejs Beļeckis © Courtesy: Skuja Braden (Ingūna Skuja and Melissa D. Braden) ©

Photographer: Aleksejs Beļeckis © Courtesy: Skuja Braden (Ingūna Skuja and Melissa D. Braden) © Photographer: Agostino Osio

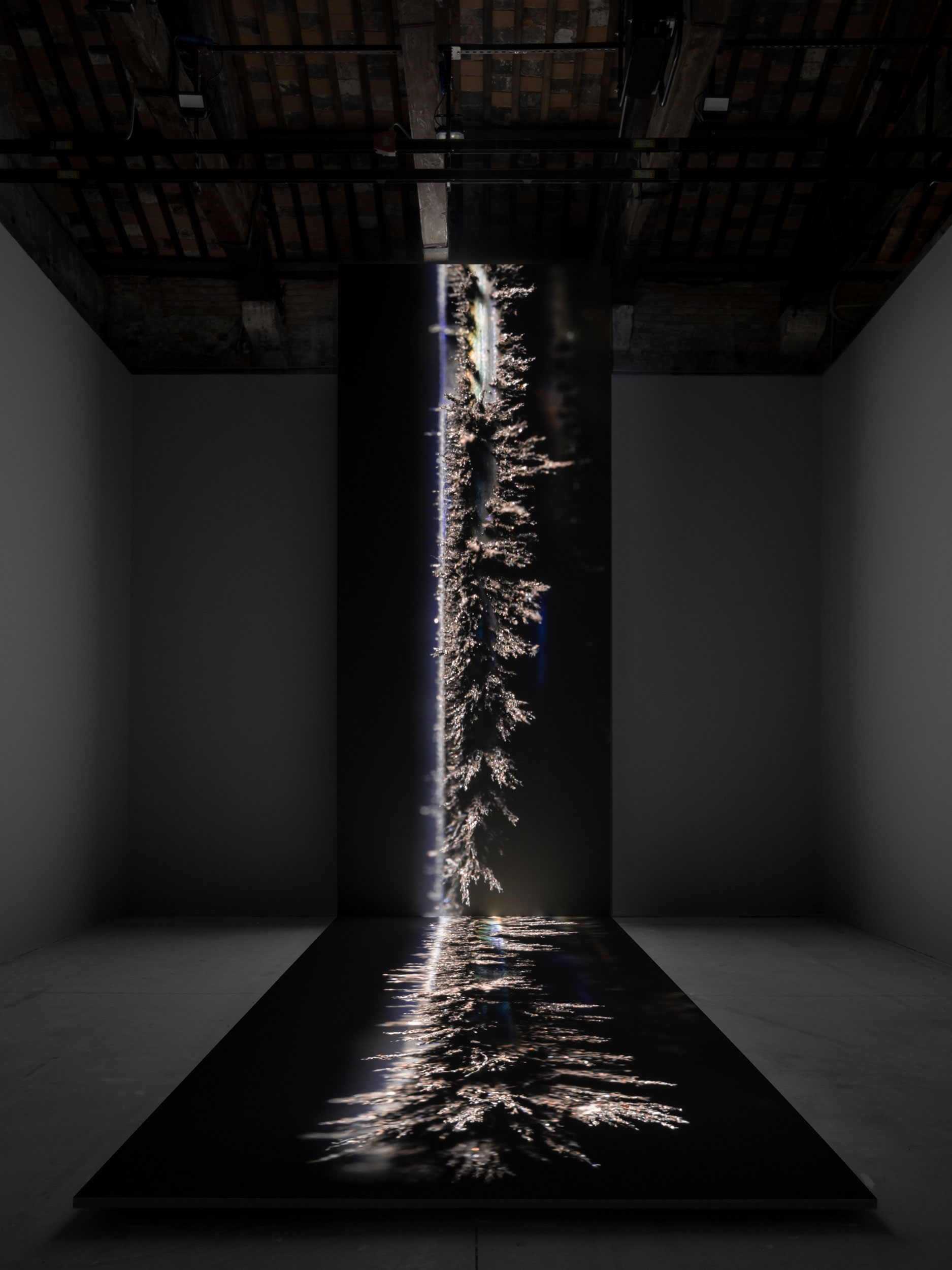

Photographer: Agostino Osio Sigurður Guðjónsson, Installation view: Perpetual Motion, Icelandic Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition -– La Biennale di Venezia, 2022, Courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary, Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Sigurður Guðjónsson, Installation view: Perpetual Motion, Icelandic Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition -– La Biennale di Venezia, 2022, Courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary, Photo: Ugo Carmeni