Everyone knows that Iceland is one of the best places in the world to be a woman, or to be queer, or even to be a creative. If you didn’t know, now you do: according to X, Y, and Z studies. So, goals accomplished, right? Well…no. When you begin to really look at, and challenge the acceptance of these rankings, cracks begin to form, and we are reminded once again that the romantic vision of a “utopia” remains in our imaginations.

For example, despite Reykjavík capturing the number 1 ranking for the most accepting city for LGBTQ+ identifying folks, laws and regulations protecting these very same people drops down to a ranking of number 11, a recent increase from its number 14 spot.

The harm in numbers like these first studies is that they create a false sense of competency, which prevents actionable steps toward continued progression. Social acceptance only goes so far, but its widespread presence is a testament that further legitimizes the need for legal backing.

The Nordic Gender-Equality Paradox introduces this idea within the realities of gender equality in the consistently top-ranking Nordic countries. Iceland included. It argues that even with immense welfare support, and progressive social attitudes, women continue to be left out of the highest positions of power. Gender norms likely play a role in this discrepancy, with studies showing men are socialized to be confident and ambitious, whereas women are socialized to be self-doubting and overly modest. And normative systems are so tied to the gender binary that anyone outside of these two gender identities is hardly ever considered, even in studies like these.

Applying the arguments of the Nordic Gender-Equality Paradox to the arts in Iceland reveals that the statistics are slowly improving, with more and more director positions in the arts being filled by women in Iceland. In 2010, three of the major public arts institutions in Iceland were directed by women. Those institutions were the National Theatre, the Reykjavík Arts Festival, and the Icelandic Dance Company. Today in 2022, only one institution, the National Theatre, is directed by a man. The Reykjavík

Art Museum, Reykjavík City Theatre, National Gallery, Reykjavík Arts Festival, Iceland Symphony Orchestra: (Chief Conductor and Artistic Director, and Managing Director), and the Iceland Dance Company are all led by a woman.

Despite this proportion having grown significantly during this time period, many of these women are the first female director appointed to lead their institutions. If not the first, they are only one out of a small handful. This is just the beginning of varied and accurate representation in the arts.

While the paradox is introduced through gender, this mentality is arguably continued amongst other dynamics here in Iceland, and issues of POC, individuals with disabilities, immigrants and refugees, and the aforementioned LGBTQ+ causes should be treated with a similar attitude that things could always be improved. As these shifts in art leadership have proven, structural change is attainable. The art scene can and should more accurately reflect Icelandic society by hiring more representative teams behind-the-scenes, realizing and funding projects by a diverse range of artists, holding these artworks in significant proportions within their collections, and ensuring that arts education is supportive and accessible for all.

The first step to breaking these inconsistencies is to acknowledge the problem in the first place. Every individual identifies with many different identities, whether it’s race and ethnicity, sexuality, gender, class, or even profession and hobbies and it is through this acknowledgment of diversity and intersectionality that allows you to stop viewing others as one-dimensional. This is exactly what Rebecca Hidalgo, Eva Björk, and Chaiwe Sól did when conceiving R.E.C. Arts Reykjavík, a collective of workshops that seeks to promote diversity in the arts, especially in their own field of performing arts. Don’t be mistaken, R.E.C. Arts Reykjavík often acknowledges the privileges of living and working in Iceland and gives credit where it’s due. But they noticed that these advantages often left out experiences similar to their own, and of their wide-ranging community in Reykjavík. In this interview with Amanda Poorvu, R.E.C Arts Reykjavík gives insight into the origins of the project, their mission, and where they are headed next.

R.E.C Arts Reykjavík is a creative team & collective founded in late 2021 by Rebecca Hidalgo, Eva Björk and Chaiwe Sól. Their mission is to bring diversity, visibility, and representation of marginalized groups living in Iceland to mainstream theatre, dance, music, and art scenes. They aim to build and provide a platform to uplift minority voices; host workshops for those 18+ who identify as being from a minority background; and encourage empathy and change through education, discussion, art, and storytelling. They are on facebook and instagram at @recartsrvk and you can email them at recartsrvk@gmail.com for consulting, collaborating and creating work, or sharing the work of artists from minority backgrounds living in Iceland.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Amanda Poorvu: Hi Chaiwe, Eva, and Rebecca, Congratulations on the launch and success of R.E.C (pronounced: REC) Arts Reykjavík! Let’s start from the beginning? How did this project come about?

Rebecca Hidalgo: Well, we started writing a super political musical. We applied to direct it and make it at a high school here, and we got turned down. We also realized it was probably for the best because our musical was very political: about minorities, about diversity…and the school was very not diverse–

Eva Björk: It was one of the most privileged schools.

RH: –and they happen to have a lot of funding for the arts program. But we saw the importance of still doing it. We said, “okay there are minority artists in Iceland to do this, but there are so many that are not being built up, that do not have a platform, so we need to start from scratch.” Rather than writing the musical and hiring professionals to be in it, we want to hire both professionals and amateurs. We need to train these people; we need to find these people. How do we find these people?

Chaiwe Sól: Also, just the lack the diverse representation is what got to us. We found a mutual ground within ourselves living here in Iceland, and our experiences. And we were just like, “People need to hear us, people need to hear what we’re experiencing.”

EB: I also think the arts are missing everything that is not–how do you say it?

RH: Mainstream

EB: Yeah, mainstream. In my family, there are people with disabilities and they are kind of tossed aside. There is so much that we could do.

RH: That’s one of our main goals and missions because like I said, all three of us come from very different backgrounds, we all live in Iceland, two of us have lived in Iceland for a majority of their lives, and–

CS: One of us is adopted black Icelandic, working in education and theater.

RH: Queer foreign Latina.

EB: [I’m working] in a man’s world.

RH: All of the above.

EB: (points to herself and Chaiwe) single moms.

RH: –we are all very different people living in Iceland. That’s still rarely seen, at least in mainstream media. There are a lot of great works happening but those works are not being built up or funded as they should be.

CS: We were like, “What are we going to do about it?” so we got together and conducted this group. Instead of telling our stories, we wanted to have people tell their stories themselves. That led us to R.E.C Arts and the workshops.

Your mission statement states that you aim to bring “diversity, visibility, access and representation” to marginalized groups. In the workshops, we often talk about the importance of these terms. What do these words mean to you? And how do they differ from each other?

EB: I would say that diversity doesn’t come in one form, so if you are going to [seek diversity], you have to look into all minorities. There is not one persona in each minority group.

CS: All the art stuff in Iceland that is available, theater, dance classes, etc. cost money. And certain minorities don’t have access to that kind of money, which means they don’t have access to that. We wanted to be able to find a way to open up that portal for people.

RH: In terms of access, there are a few different ways that comes across. You have access purely in the physical, in the world of disabilities, access in having a sign language interpreter, and having wheelchair access, having seating for wheelchairs that are not behind a column or something like that. I do think Icelanders do a good job in that sense. Obviously, it could always be better.

There is access in nepotism. As Chaiwe was saying, there are not a lot of people of minority backgrounds out there with representation. They don’t have a family member in the industry but have always wanted to be on stage. But then they see that there are a lot of walls put up, so they feel like they don’t have access to the scene, and they get discouraged and don’t go into it. Which then feeds into the lack of representation. in terms of visibility, it’s pretty simple. Being seen. Having a minority on stage or on tv.

AP: But not only in the background.

RH: Exactly, not as a way to tick a box. That also comes with proper representation.

CS: The right representation has to be presented. Like how single moms in theater or movies are always portrayed as smoking, drinking, and completely falling apart. Why can’t we just represent single moms as someone who’s hardworking? She’s running a law firm and she’s doing her thing. That does exist It’s really sad when we have to fictionalize the minority to make it work for society. We are helping feed this society. As artists, we have to take responsibility for the stories that we’re telling because by telling that story, whether it’s to a little kid or to a grown-up, that person walks away thinking that is the truth. This is the truth that they stand by and the truth that they start to live by. If we don’t change that truth to make it match the actual truth, we have a problem.

EB: If you are a minority, and you want to go to a class–a dance class or whatever is going on–it’s also hard [to show up] if you are different. People don’t always respect what is different, which is so sad because we can learn so much from each other. We don’t learn when we are always the same.

RH: There has to be a balance of stories. There are deep ones, but that can’t be all we tell [in order] to have diverse representation.

CS: …the hairdresser, ghetto, Black girl; the single moms; the cliché characters…

RH: The cis, white, gay, best friend who is only interested in fashion, and doesn’t actually have a storyline other than saying sassy lines, and being the sidekick. Queer characters are way more deep than that. Also, picking the correct people to play these characters. It’s simply having an actual trans person play a trans character. Beyond that, the people behind-the-scenes matter with representation. That is the difference between visibility and representation. You can have a person of color on stage, but if they are the only person of color, and the director, choreographer, makeup team, producer, and everybody else is white, then it is whitewashed. I know from my experience, being one of the only minorities in a production, I did feel at one point like the annoying person. [Either] always calling things out or being like, “Ugh this is not my place, I don’t have the energy for that today.”

CS: The minority is tired of always speaking up, and what is happening is that the majority is just not aware of what’s really happening, and how it affects the other person. For us, that is where we can see our niche. We want to bring awareness.

While your workshops have individual themes, R.E.C. Arts Reykjavík is open to all definitions of minorities, including POC, LGBTQIA+, Disabled, Refugee and Immigrant folks, etc. because all of these identities are interconnected on an intersectional level. How does this shape the kinds of discussions you are having?

RH: I think it comes with openness.

CS: It’s quite beautiful to see the stories actually evolving. We have a storytelling game where you have a ball, and then you say a word, and somebody else says another word or shares something that connects to it. It’s amazing to see that we have created a space where people allow themselves to be so vulnerable and genuine and dig so deep. If one person sees [another] person doing that, it’s almost like a snowball

RH: A lot of it comes from the three of us being very open from the beginning. I think at the beginning of our online workshops, we were being very open about who we are, and where we come from. Then that allows people to come in. I think one of the most beautiful things we’ve seen during our storytelling exercises is people finding common ground with each other.

CS: We always said that we wanted to create a family. When people walk in, we want them to feel like, “I’m going to see these people, and they are my family. They are going to accept me for who I am. For these three hours, we are going to be having a good time.” Somehow, we have managed to create that for people.

Iceland has a small, tight-knit population and is often considered a progressive “utopia” in regard to many social justice issues, especially when it comes to gender and sexuality. Yet this has created a contradiction, called the Nordic Gender-Equality Paradox, which can lead to a lack of policy or legislation when it seems like there is no problem to begin with. You don’t challenge things when you think they are successful. How has this shown up in the arts here? What structures would you like to see put in place to strive toward equality?

RH: Our mission when we call out institutions is to do it in an educational way. Not saying, “Here’s why you’re bad.” but adding, “…and here’s how you can do better.”

EB: The best way to get respect is to respect others, so we do respect everyone. It’s human nature. We’re not saying anybody is mean, but once we have educated you and you still don’t want to turn the page, that’s when we can say, “Oh, okay, so you just don’t want change.”

CS: Everybody deserves a chance.

RH: I’ve heard people say, “I don’t think I’m qualified to come to these workshops, but can I?” and they happen to be a cis, white, woman or a cis, straight, woman. I’m like, “We don’t advertise it, but by being a woman, you are still considered a minority.” So, come and learn from others, and know your privilege, but also know that you can still complain. You have every right to complain. I think in Iceland, they’ve been taught that “People have it worse in other places.”

EB: I even think white, cis men who are queer, or people who have minority family members [can come]. Everybody that has this mindset is welcome, as long as you’re not in that mood thinking you’re better than others.

RH: I think being a minority is also more of a political and systematic thing. Being a cis, white, straight male, in our eyes is the ultimate privilege. Of course, you can be a minority in a certain situation but in society, you are never one. You can walk on the streets safely by the way that you look. If you dress differently, that’s a whole other thing but if you dress how society says is okay for a straight white male, you’re safe. A lot of privilege is about safety. How you look is the first thing people see.

EB: It also does matter when people are in different work fields. I’m a carpenter, [working] in a male field for 12 years and I very much feel like I have to work much, much harder to be allowed to hold a machine or something. It’s like when you walk into a wall over and over again. And then you either stop trying, or you try to create a new way. I would say this is a new way we are trying to create.

RH: We always talk about the big theaters and the big media institutions. They are slowly changing, and things are being pushed, but it’s like they don’t see a need or reason to change things that have worked for 50-whatever years. They’re ignoring the things that do need to be changed.

CS: They don’t want to put in the effort. There is an effort that goes into change

EB: It’s like, what if airplane engineers were like “Let’s just do it the old way.”

RH: I think an actual, productive way to change the structure in the arts and theater, in my opinion–we’ve discussed this as a group -is to have a quota. To have some sort of quota like, “We have to specifically hire artists of color, queer artists, artists of minority backgrounds” to create work for these institutions. Not just a one-off, you have to have a certain amount every season. And not just one director, but a team of diverse people.

There’s a theater company up in Akureyri and it’s doing the show Hair, which takes place in the US in the 1960s, and a lot of the show has to deal with racial relations between African Americans and white Americans. [One of the] roles that they cast is meant for a woman of color and is being played by a white woman. You know, we want the Icelandic theater community to see this is not okay.

There are enough people of color here to be cast in these roles. We’ve also heard in our workshops that as an actor, sometimes you feel like you don’t have the authority to speak up because it’s a job. So even though there is one actor of color in the show, whether or not he agrees with a white girl playing a role written for a black woman, it’s still not his responsibility to speak up. Doing a show about a character of color and writing their roles out, that’s called erasure. That’s also not okay. Out of a thousand musical theater shows you could do… I would rather see a less trained person of color play the role than a trained white actor pretending to be that character.

CS: That just boils down to doing the right representation. If it’s a black woman’s story it has to be a black person playing it, a trans person’s story has to be played by a trans person. It can’t just be a random actor.

What would you say to someone who does not agree with quotas?

EB: Excuse me, but the same truths have been told for how many years? Isn’t it just time for a shift? Nobody is taking anything away from anybody. People want to go to the theater, but there are not that many plays out there that a lot of different people want to go to. One very big thing is that we pay taxes here for the theater. There is enough space for everyone. People need to stop thinking, “If you’re going to take this spot, where am I going to sit?”

CS: I mean, the quota aspect is a little tricky because what is the right quota? It gets super complicated. But the idea of being open to some sort of quota starts this ideology. It doesn’t have to be so written and so structured.

EB: If you think about it, if you go to a tryout for a play, they are always looking for something. It’s already there. If you’re blonde it’s going to work, or you have dark hair it’s gonna work. So, this quota is not overstepping what was already there before. It’s just giving more variety.

CS: Versatility. If you’re telling a story about a girl in Iceland, have everyone come and try out. And maybe you’ll see something in that not-blonde-and-blue-eyed girl that’s part Sri Lankan, part Icelandic, and speaks perfect Icelandic. I mean there also has to be an opportunity for these people We have to move with the times, and you can’t just choose to exclude a whole population from your own population. It just doesn’t make sense, it’s not right. Aside from that, minorities are also a huge part of the people who are running our systems. So, they also deserve to have a platform for themselves. Just recently, they finally made a Polish play to call out to the Polish community, with Polish actors. I thought that was amazing. It’s like, Polish people have been living here–

RH: For how long?

CS: Exactly. That’s amazing, but it shouldn’t have to take 40 years for you to be able to see yourself on stage.

RH: It isn’t a long-term thing. It’s just a short-term solution with long-term goals. Then it will naturally happen. That’s the goal.

CS: Also, the quota allows for different people to come together and learn about each other. That accessibility is so important. It’s something we discuss with education where I say: a headmaster who doesn’t have a foreign friend is less likely to think about the minority kids in our school and the issues that they could be experiencing. The ability to be able to know about minorities and their struggles opens up your mind. And that’s what the quota would technically do.

EB: It takes effort when you have always tried to fit into the box, to step out. It takes a lot of courage. And I think the theater and the arts are beginning to open up to change. As soon as it is normalized in the media, it’s conditioned in people.

RH: Last year, an actress of color called the national theater out publicly on social media because they released a poster of all their house actors, and every single person in that photo was white. And from my knowledge, the majority of the people are also cis and straight. She was like “I’m not saying anything bad about these people, they are all my friends, but intuitionally, this needs to change.” Granted, for this season they did hire a few more actors of color, but it still felt like tokenism.

CS: And “backgroundism”

RH: It was like “Throw them in the background here. Oh, and let’s make sure we get them for the poster this year!” That’s how it felt to me.

EB: Not everybody owns up to their mistakes right away, but I always want to also look at the positive, that this is maybe the start of something. That it will roll the ball because we are now here to poke and poke and poke and poke. We have to reinforce this and keep going.

Discrimination in Iceland does not only appear as blatant aggression and exclusion but also in more subtle inequities or in a lack of opportunities. What are some of the examples of microaggressions in the art scene here that people might not be aware of? Do you have any personal experience with this that you can share?

RH: From my experience working on a show at the theater, there was an incident of an actor wanting to do blackface in their role, and not understanding why that was not okay. [They then] directly asked only the people of color in the cast why it was not okay. There were some other things having to do with hair and makeup, with racial and cultural appropriation that I became the ambassador on, apparently. But again, they took it into account and did want to educate people after they had made the mistake. I’m happy it became a teaching moment but if you have had a more diverse creative team, it wouldn’t have had to be there.

Another thing is from a review that came out about a show. Out of the whole cast, there were three minorities, one of which is actually a pretty well-known actor in Iceland. The review mentioned every single other person’s name on the cast and the creative team somewhere in the review. Every single person’s name and the character they played, or the role that they played, except for the three (including myself) minorities. It was weird. Nobody from the creative team or the theater saw this and was like, “You forgot ____.” As creatives, it is important for your records –even if it’s bad press, at least it’s there.

CS: Because you’re constantly fighting your battles…

RH: I was exhausted. I was like, “There are so many other things that are more important.”

CS: When to speak up? When not to speak up? When will this get me in trouble with my job? The tight-knit-ness [appears] as soon as you speak up. There are plenty of people who are like, “I want to come to your workshops but I’m scared because Iceland is so small.” There is also that insecurity because it’s a small population. If I were to give an example, I would say being spoken to in English when you walk into a store.

RH: Even after you speak in Icelandic, that’s the big one.

CS: No, no, having a whole conversation in Icelandic and they still continue to talk in English…

RH: We’ve been collaborating with the girls from Antirasictanir, and they’re young and super brave and amazing. They have similar experiences to Chaiwe, and it’s so crazy to see these young, Black girls in Iceland, who have lived here their whole lives and still are treated a certain way as if they are not part of the community.

CS: I mean there are a lot of little microaggressions we experience every day. [In theater] There is a lot of exploitation and tokenism, and taking away from people. Like, you want the story to be told but you are not giving homage and rights to people that have the story. Why are people doing this without consulting? Why is there a disconnect between taking from minorities and not feeling the need to fully give back?

RH: Appropriation is when you take from a culture and use it for your own benefit and you don’t either give back to the culture or acknowledge the culture and where it came from. You use it for profit or social media attention without actually acknowledging it. There are so many layers.

What kind of solutions to these, no matter how big or small, have you come up with in your workshops?

RH: The internet is there, it’s free and there are so many resources. It is not always a Black person or a queer person or a minority’s responsibility to do that labor and give you the information. Literally, google it. And one of the things that we’re done is that we have created a resource document of different articles, and of people on social media who do this for a living. They put out education for free and for profit.

CS: We started as R.E.C. arts and we were like, “Hmm, should we become an agency?” We can connect people to artists and dancers etc. and also make sure that when they do go to gigs, they get paid correctly and are represented correctly. That’s what we mean by giving back to the community you are taking from. It’s not enough just to take. They need to feel like they are getting help when they are putting their stories out there.

EB: We were also talking about how we to be that medium for helping out and educating the theater, so we’re going to offer that, too. So, institutions can always talk to us and nothing is a bad question.

RH: I think people are afraid to ask questions.

CS: People don’t want to feel stupid.

AP: Now there is a fear not only of getting called out for bad actions, but also for performativity if you try to fix them.

RH: I think there is a way of fixing something that isn’t necessarily performative activism. I think when you are honest and transparent about the mistakes that you’ve made, it’s even better. Because it’s education. You could put out a statement that says “We made a messed up. Things should have been done ____ way. We are going to take the time to do properly do that. And we are going to be open about it because we want people to learn.”

CS: It’s being able to vocalize yourself. Making people feel seen and heard is what matters.

EB: If you don’t feel that you are part of the community, how are you supposed to

feel like you have a purpose?

RH: That goes back to why representation matters.

R.E.C. Arts Reykjavík started during the pandemic over a series of zoom workshops that have recently moved to in-person. What else are you hoping to pursue in the future? Where do you see this community growing?

EB: The reason why we started our workshops on zoom is because of COVID-19. We always were planning on being live.

RH: The next thing that we are doing is that we have a whole-day takeover at Iðnó during the Reykjavík Arts Festival. We’re going to be hosting different educational panels, some workshops, and classes, and we’re going to be showcasing performances that are being built within our workshops. Also, some curated performances by other local artists of minority backgrounds to give them a platform. We basically wanted to show the higher-ups in the Icelandic art scene what they’re missing, and that they are people here that are talented and have amazing ideas, and have a voice and a story. So that’s our short-term thing.

EB: We are letting it grow. It is exciting to see. It is hard sometimes when you are creating something to not have a complete plan, but we have a structure and we want to be open to letting something new grow. We realized when we started this that there are so many minority groups out there trying to do their own, similar thing so this is kind of a platform for everyone to have a space to do something on one big day.

RH: The panels are going to be themed and the biggest thing about it, in terms of education, is going to be “Hey, you think this isn’t a problem? Let’s show you why it is a problem AND how you can fix it.”

A lot of people aren’t interesting in solving it, or they don’t know how to solve an issue so they just say “let’s leave it for another time” because there is that fear of not knowing how to fix it and doing something wrong.

CS: We say education and awareness, but our plan is more about giving people tools, to be able to address situations seriously. Giving people the power and the courage to stand up for something they would have never stood up for, so when you see something wrong you can be an active ally.

EB: Especially getting white people amongst white people to say something. Because people always think it’s not their problem, that it’s not affecting them. You can always do it in a polite way, and not be aggressive and make the other person feel stupid. It is 2022, we should try to talk a little bit more respectfully about everyone.

RH: All of the things we are talking about are also relevant in the United States, and here or there, but I think because Iceland is such a small country, it’s so frustrating to see. Because it is such a small country, things can happen very fast. It is supposed to be one of the most “progressive,” “equal” countries. The fact is that we’re seeing it from the inside, and we’re saying “It’s actually not, and here’s how we can fix it” and people are still insisting they want to keep it the same. That’s why we see it as a bigger problem than in some other countries.

CS: We’re not coming together. We need to come together whether we’re Black-Icelandic, Green-Icelandic, or Russian-Icelandic. We’re still Icelandic. This concept is important to me because I have a mixed son, and he is Icelandic. I don’t want him to ever experience somebody asking him “Where are you from?” I was adopted and have an Icelandic mom, I am an Icelander and my whole family is Icelandic, his father is Icelandic, and his grandparents…this is all he knows. I don’t need someone to judge him by his color and take being Icelandic away from him.

RH: I think one of the big reasons why people think there is no racism in Iceland, is because in the United States for example, there is a very clear, systematic history of racism. Whereas here, sure there are histories of racism but there is nothing as specific as the North Atlantic Slave Trade. But the mindset still penetrates within. Especially if you follow Antirasistarnir, they have been so blunt about the racist experiences in Iceland that they’ve had.

EB: We’ve also talked about more development because a lot of the people who come to our workshops have kids. We would like maybe later on–to be able to host workshops for kids of minorities. Because then they meet each other and don’t have that feeling of being different. We’re always finding new and more ways to make this a better environment for the people that haven’t been supported in that way.

CS: Creating this community is very, very important for us. It’s something that we all share very deeply and we’re trying to help and protect other people that could possibly be going through this. We know what was not done for us and we’re like “These are the things we wish would have happened and now we want to do this for the people.”

Every workshop ends with the question: Why does representation matter to you? What have been some of the most interesting or inspiring answers that you’ve received so far?

RH: We posted some of the answers on our Instagram, which you can read here, and here.

And to close, I’ll turn the question back to you. Why does representation matter to you?

EB: Because everybody needs to be seen. It’s all in that. Everybody needs to be recognized and have value in their life. I mean why are we here? It’s not like it’s easy.

RH: Specifically for me, if I hadn’t had the opportunity of seeing someone like myself on stage having their story represented, as an aspiring performer as a kid, I don’t think I would have been as motivated or excited to go into this industry.

Amanda Poorvu

Amanda Poorvu graduated in 2019 from Oberlin College with a BA in Studio Art and is part of the first graduating class of the MA in Curatorial Practices at Iceland University of the Arts. Her graduation project is a virtual exhibition titled Funny People and can be accessed at funnypeopleexhibition.com.

Chaiwe Sól is an activist, artist, and educator; but most importantly a woman of color and a mother. She was born in Zambia and adopted by an Icelandic mother. As an Icelandic person of color, she has experienced and dealt with a fair amount of racism, discrimination, and the difficulties of understanding what it means to “be Icelandic”. She developed a thick skin; cultivating survival methods in order to find her footing and voice in the system. Her struggles within society led her to pursue a career in education. She is currently completing a Master’s in Theatre Education at HÍ, with a focus on using theatre as a platform to teach Icelandic as a second or third language. Chaiwe is currently working at Kársneskólí teaching Icelandic as a second language. As a mother to a mixed-raced child, Chaiwe strives to create a better environment for her child. She aims to create footprints in the Icelandic community to make it easier for her son to be Icelandic.

Eva Björk is a woman of many trades and many lives who resists throughout her existence. She is a queer single mother of two young adults. She is an activist and educator; with a Masters’ in house & furniture carpentry and a degree in teaching. As a woman in a “man’s” work field, she faced a sexist and chauvinist environment every day as she worked her way up the ranks. Her force has been recognized by many, and during her time teaching, she was invited to speak at a Women in STEM conference. Her experiences, childhood, and upbringing have made her a strong advocate for societal awareness of mental health and disability. She is now studying Psychology and pursuing a career as a practicing psychologist; her main goal is to teach people respect, communication, empathy, and understanding.

Rebecca Hidalgo is a multidisciplinary artist from Brooklyn, New York. She graduated from NYU Tisch School of the Arts (Bachelor of Fine Arts in Drama) and is a professional actor, dancer, choreographer, musician/songwriter, and artistic collaborator. As a child of Dominican immigrants, and as a queer woman, Rebecca has fought with culture clashes and expectations while finding beauty in both chosen and biological families. Many of her original artistic works address these conflicts; exposing the deep-rooted sexism, racism, and classism within the Latin community. This has fueled her artistic mission: to bring groups of diverse people and stories to the stage and screen. In 2018 Rebecca moved to Iceland and has since been working in the professional theatre scene and arts education. She very much sees the space, potential, and absolute necessity to bring the Icelandic theatre and dance scene to a new level regarding representation.

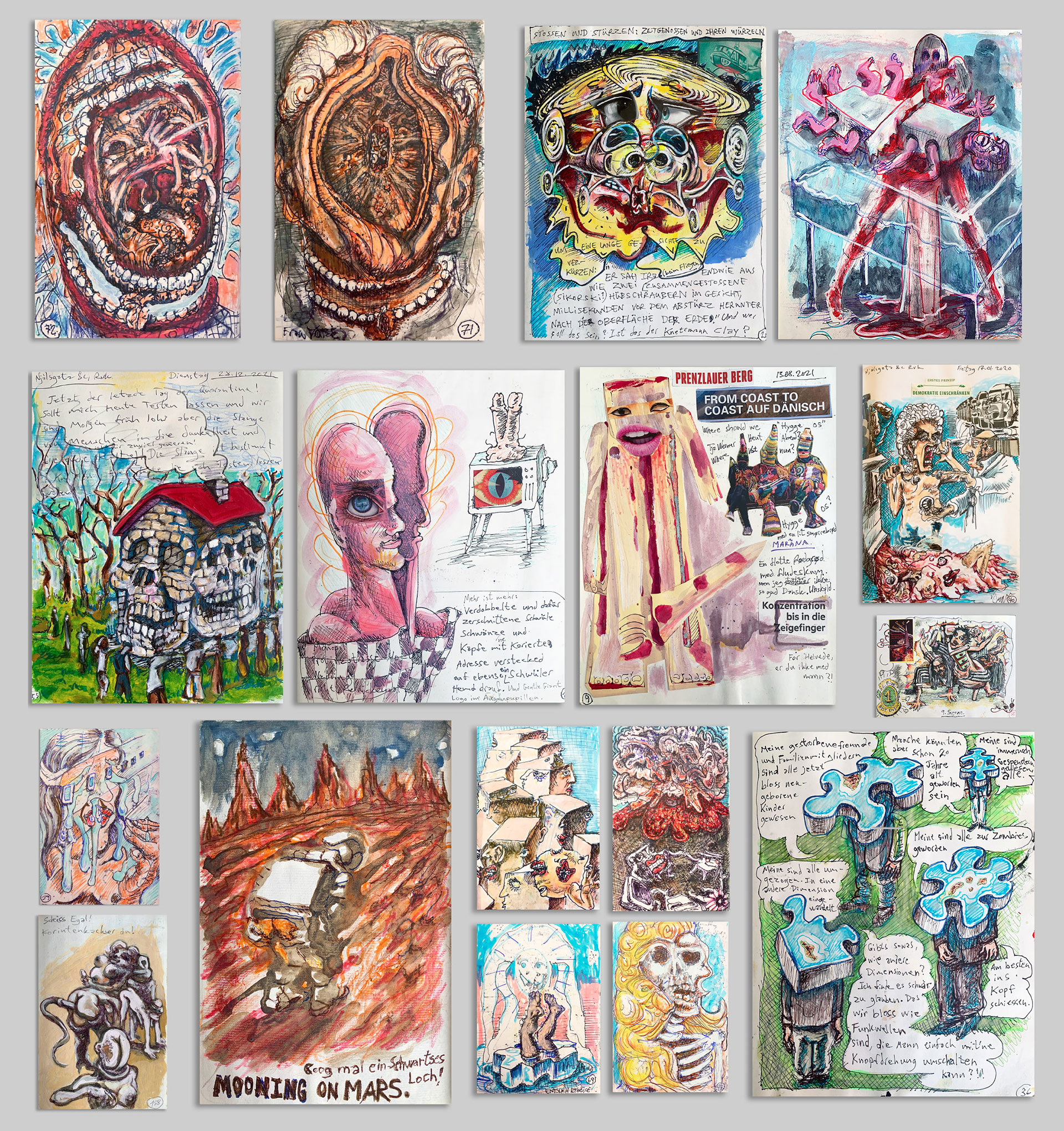

photo credit: Kaja Sigvalda.

From Komd’inn event with Sara Mia, 2022

From Komd’inn event with Sara Mia, 2022 From Komd’inn event with Sara Mia, 2022

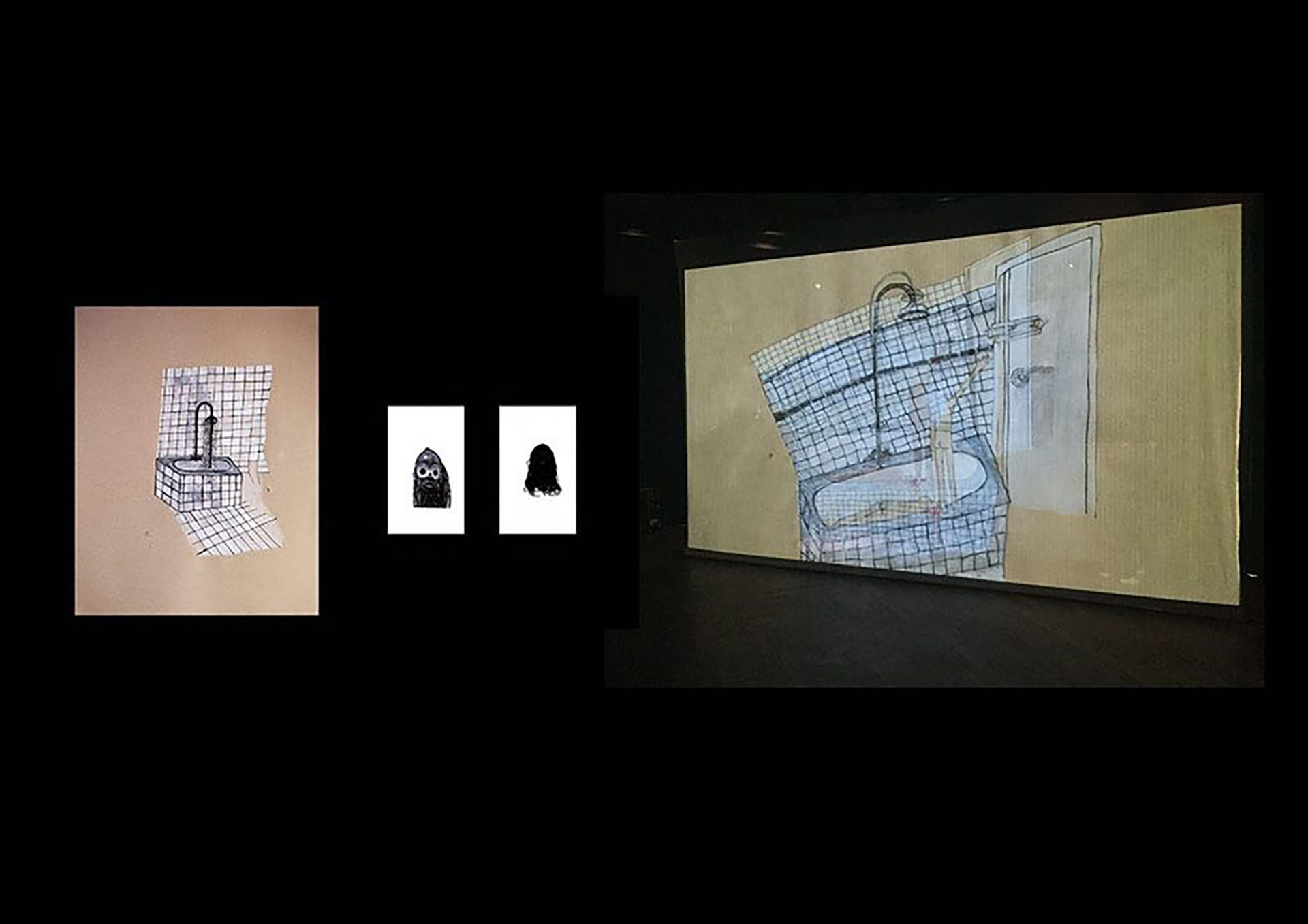

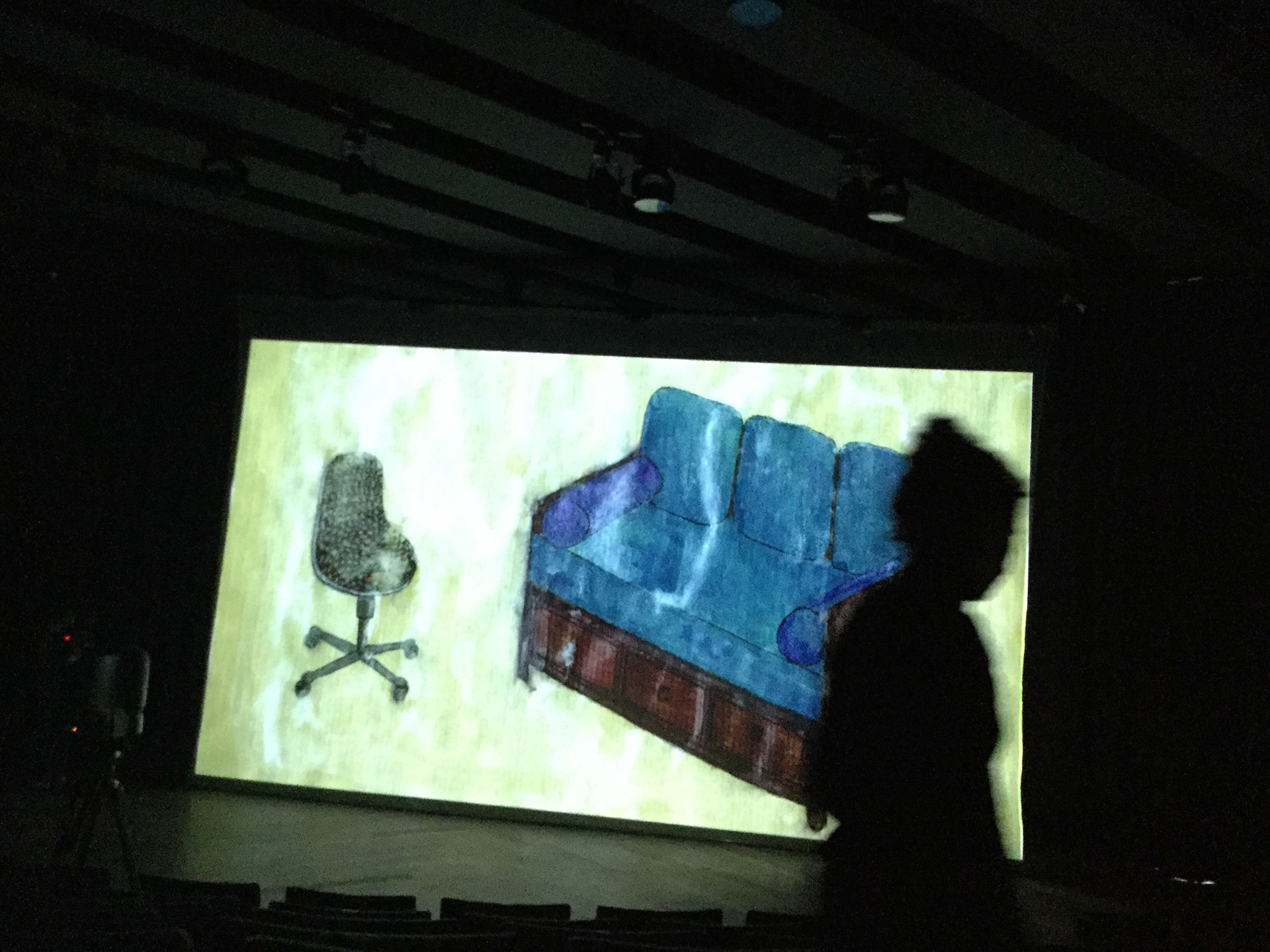

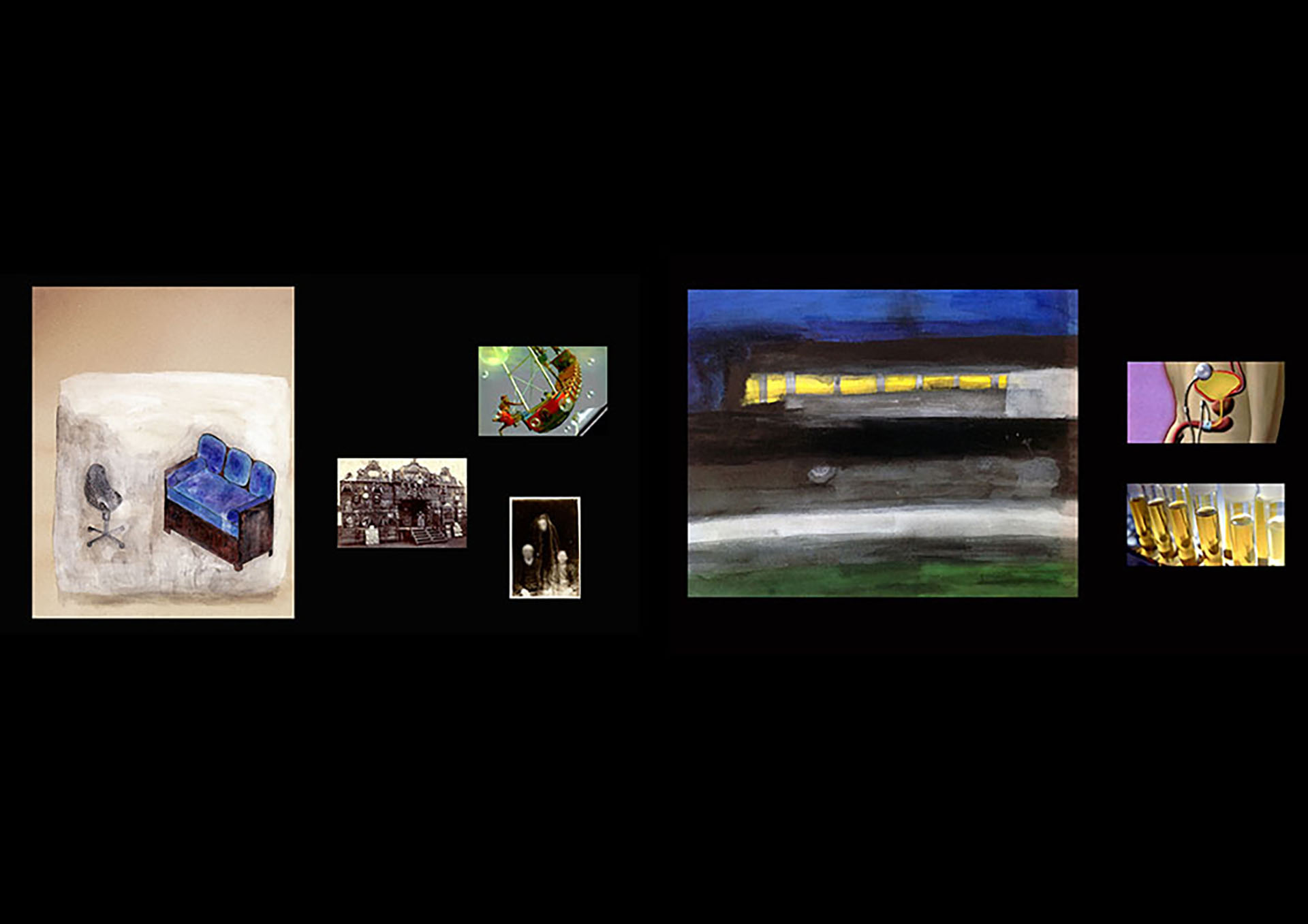

From Komd’inn event with Sara Mia, 2022 From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

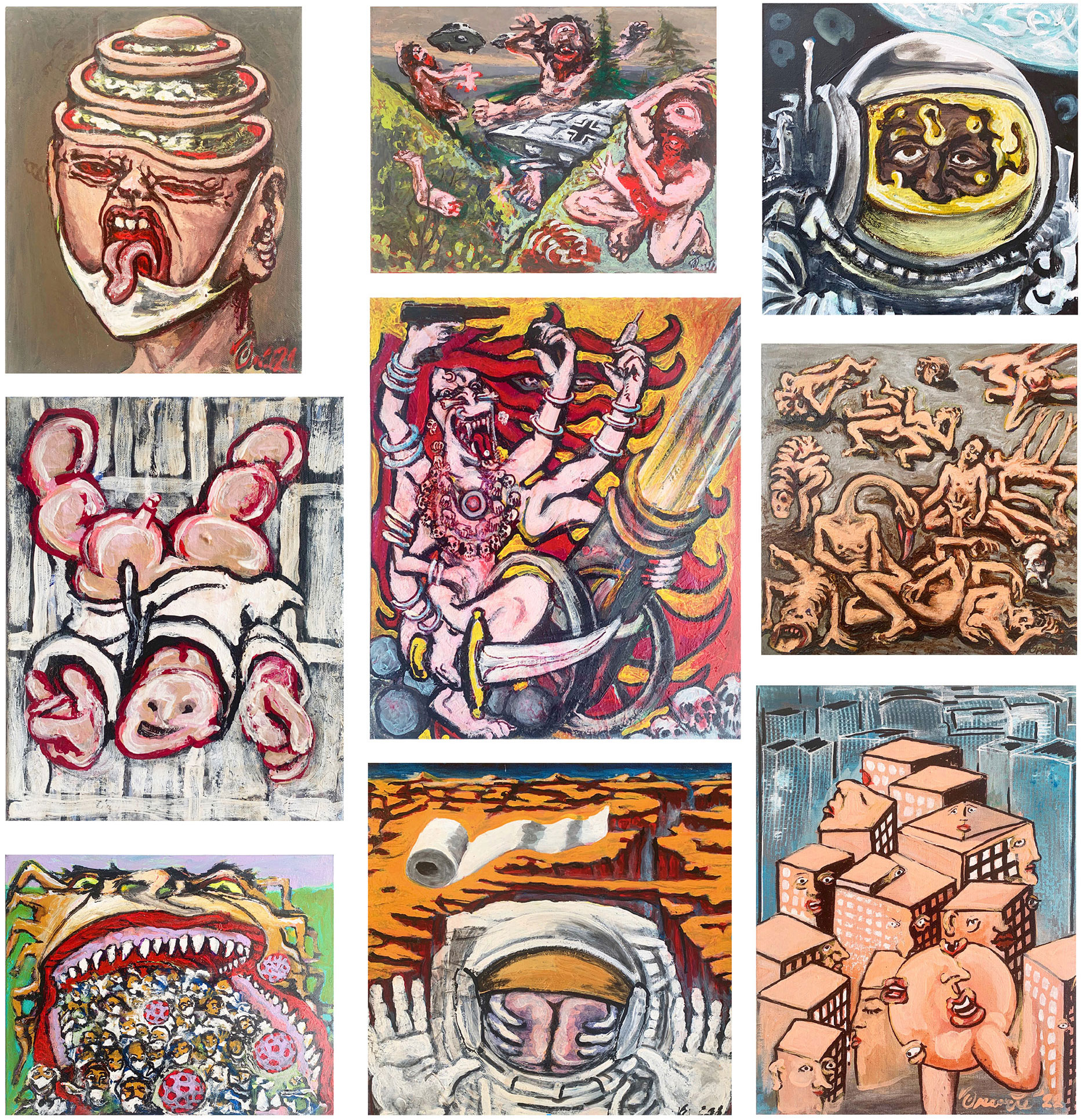

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020 From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020 From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020 From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020 From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020 From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

From Nermine El Ansari’s performance Fleeting Remembrance, Erroneous Image, 2020

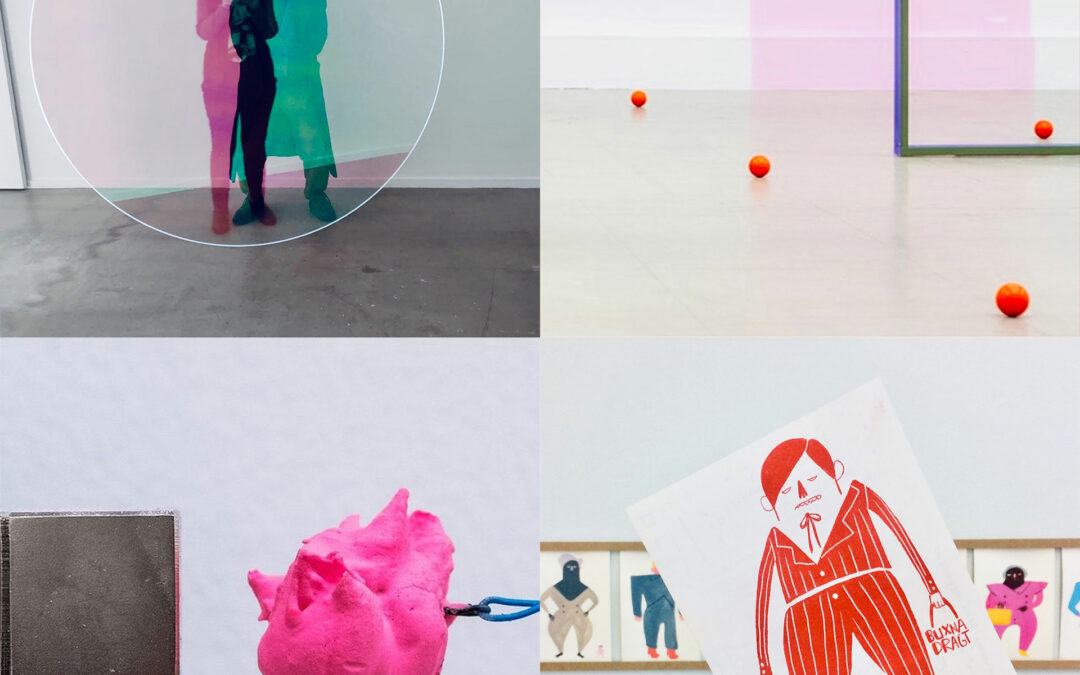

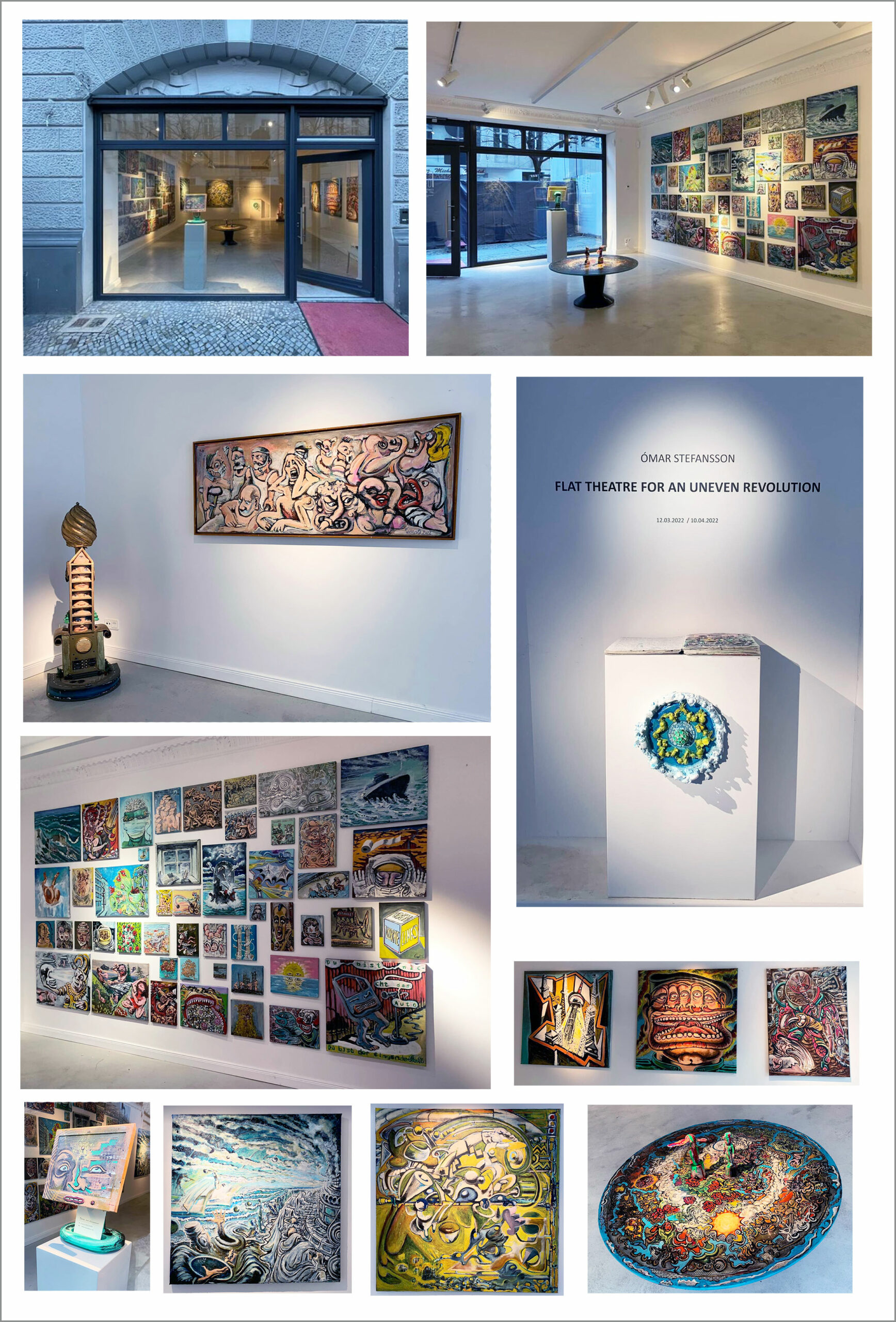

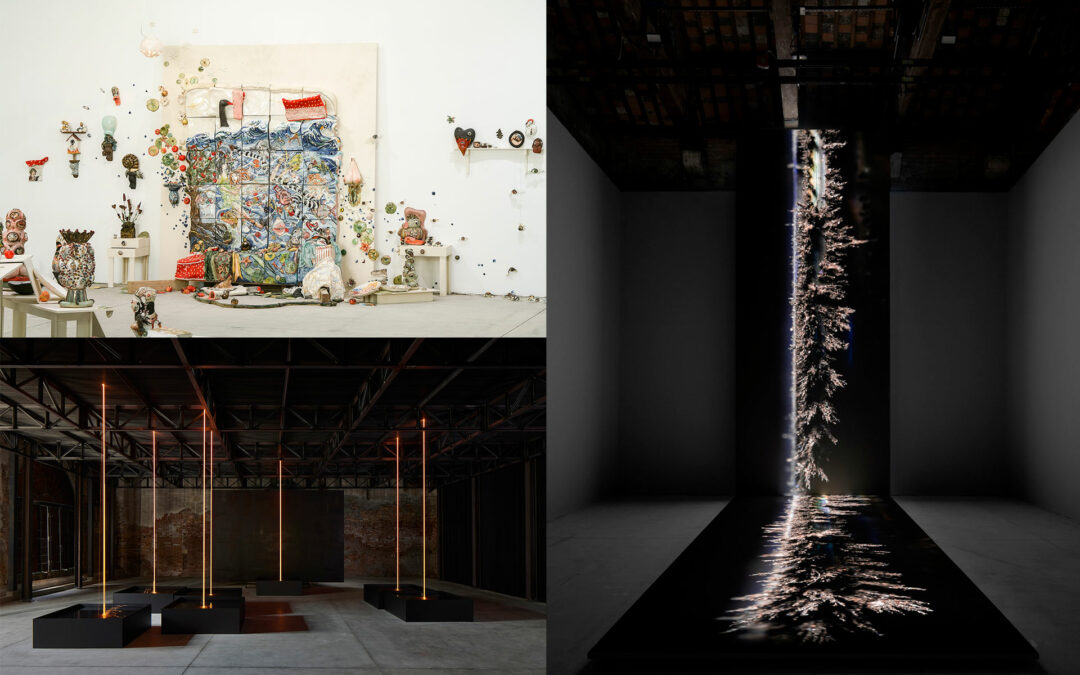

Photographer: Aleksejs Beļeckis © Courtesy: Skuja Braden (Ingūna Skuja and Melissa D. Braden) ©

Photographer: Aleksejs Beļeckis © Courtesy: Skuja Braden (Ingūna Skuja and Melissa D. Braden) © Photographer: Agostino Osio

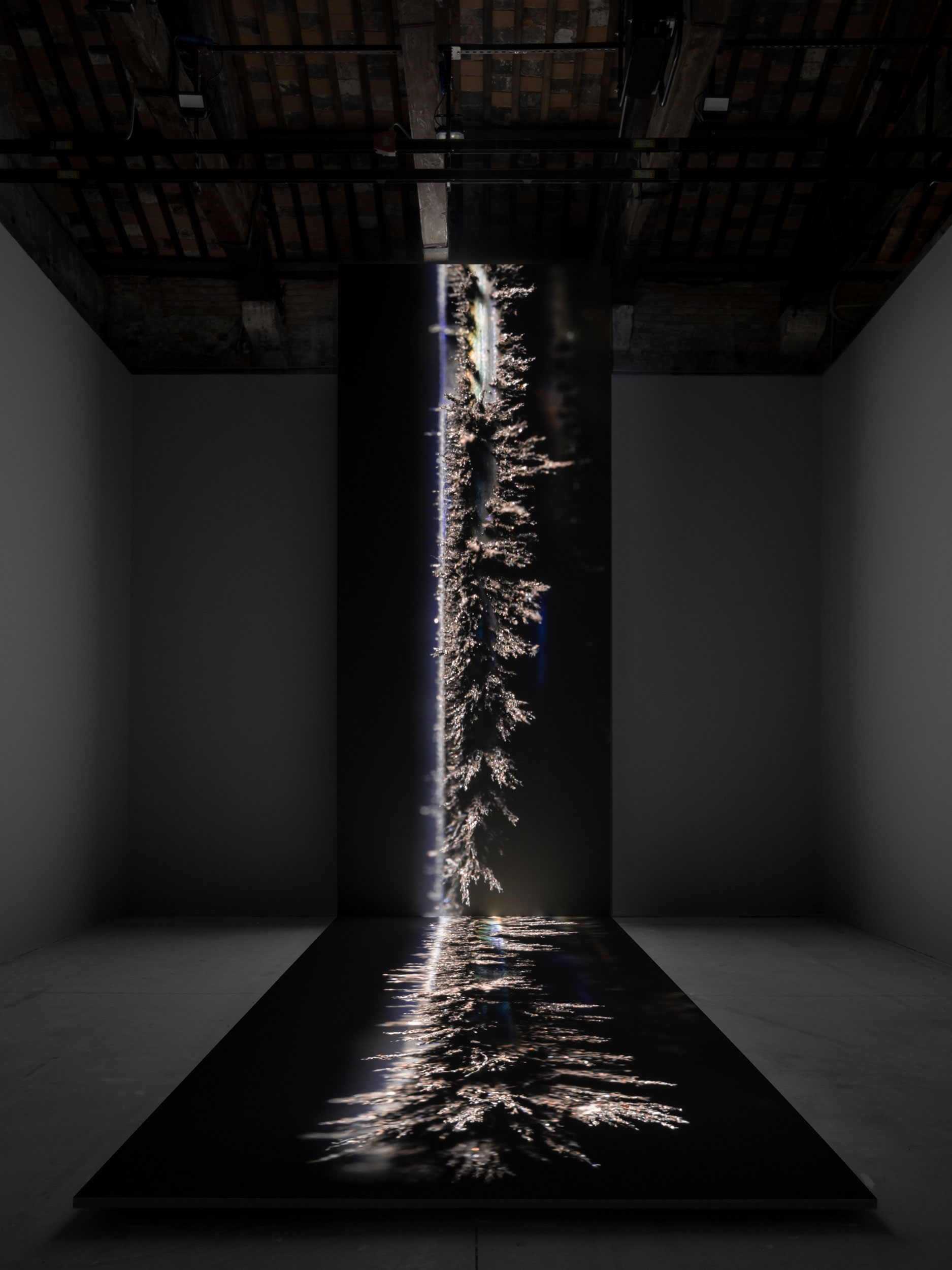

Photographer: Agostino Osio Sigurður Guðjónsson, Installation view: Perpetual Motion, Icelandic Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition -– La Biennale di Venezia, 2022, Courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary, Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Sigurður Guðjónsson, Installation view: Perpetual Motion, Icelandic Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition -– La Biennale di Venezia, 2022, Courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary, Photo: Ugo Carmeni