The Portal, Illuminated – Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson at Berg Contemporary

The Portal, Illuminated – Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson at Berg Contemporary

In a comic-book reminiscent and delightfully playful fashion, Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson unveils an intertwining of nature, human, and cosmic energy in The Thirteenth Month at Berg Contemporary. Styrmir connects the human to our supernatural and earthly elements, performatively questioning prescribed social behaviors. His graphic are grounded in knowledge, placing our existence into the context of the cosmos, alternate realities, and portals to other dimensions. His large scale drawings invoke an endless circling of galaxies and dimensions, that correlates to the endless circling of life and culture. Styrmir illuminated some mysteries behind his work, as he spoke to me about the contexts of his recently opened solo-exhibition at Berg Contemporary.

“After building a maquette of the gallery I shrunk myself and travelled into it. I became very small in this big space. So small that I forgot about everything I had done in the past. I went through many ideas for shows. Then I recalled different artworks I had made in the past five years. Images and objects I had been using alongside my performances. I made scale-models of my works and curated several doll house exhibitions inside the maquette. I opened myself up and spoke with other artists about my ideas. Artists such as Gulla and Sæmi and Hrafnhildur and Halli. I looked deep into their eyes while extracting their reflections to ferment a concept for my show. I got to choose a date for the opening. Friday the 13th in September was my choice. Then, sometime in Spring I was hanging out in the gallery searching for inspiration. A friend of the gallery, Halldór Björn, started chatting with me and I proudly invited him to my upcoming exhibition in September – on Friday the thirteenth. He looked spooked and replied: “Oh the Thirteenth Month?” In that instance I ran upstairs and reported to Ingibjörg, the gallerist, “I have a title for the show!””

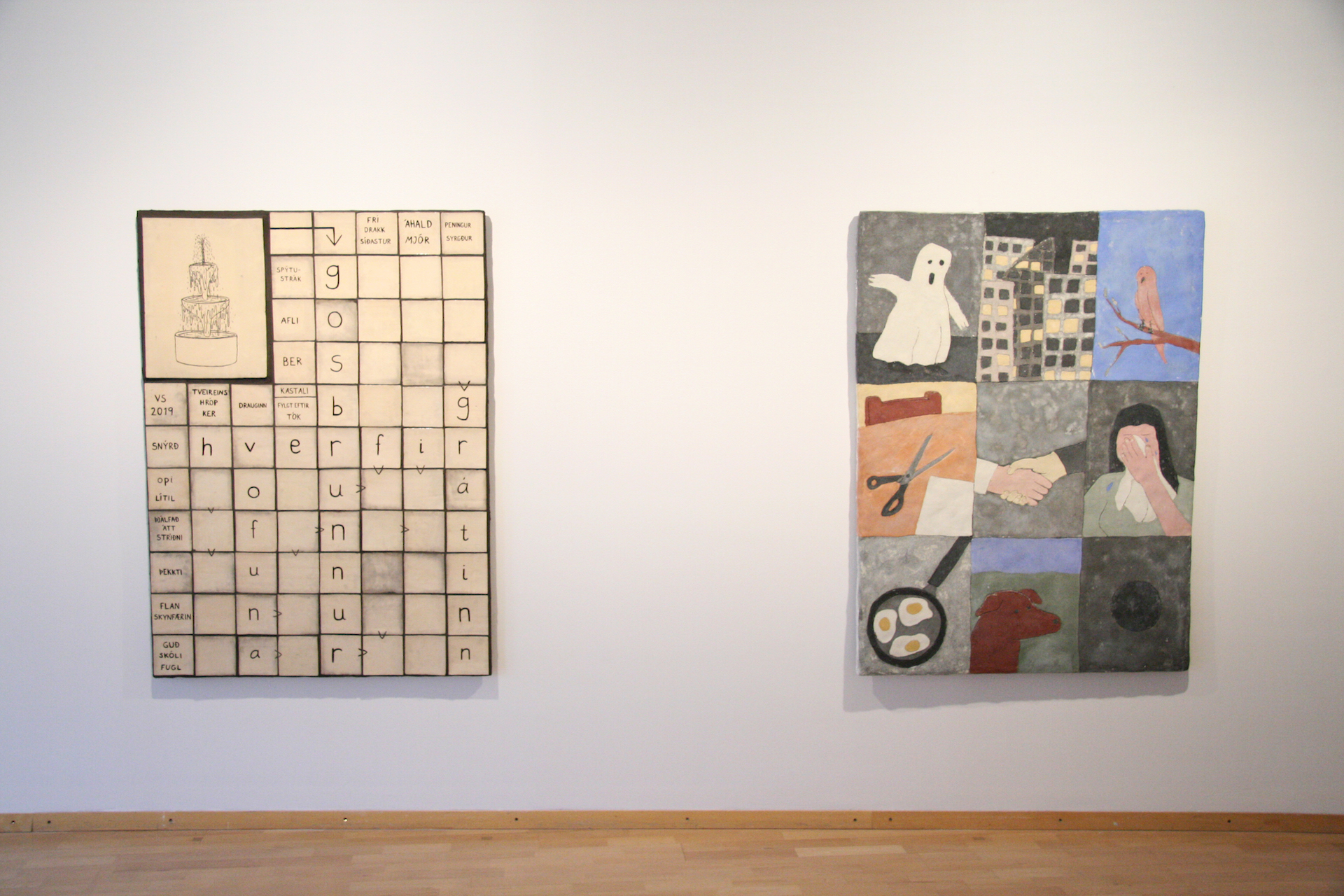

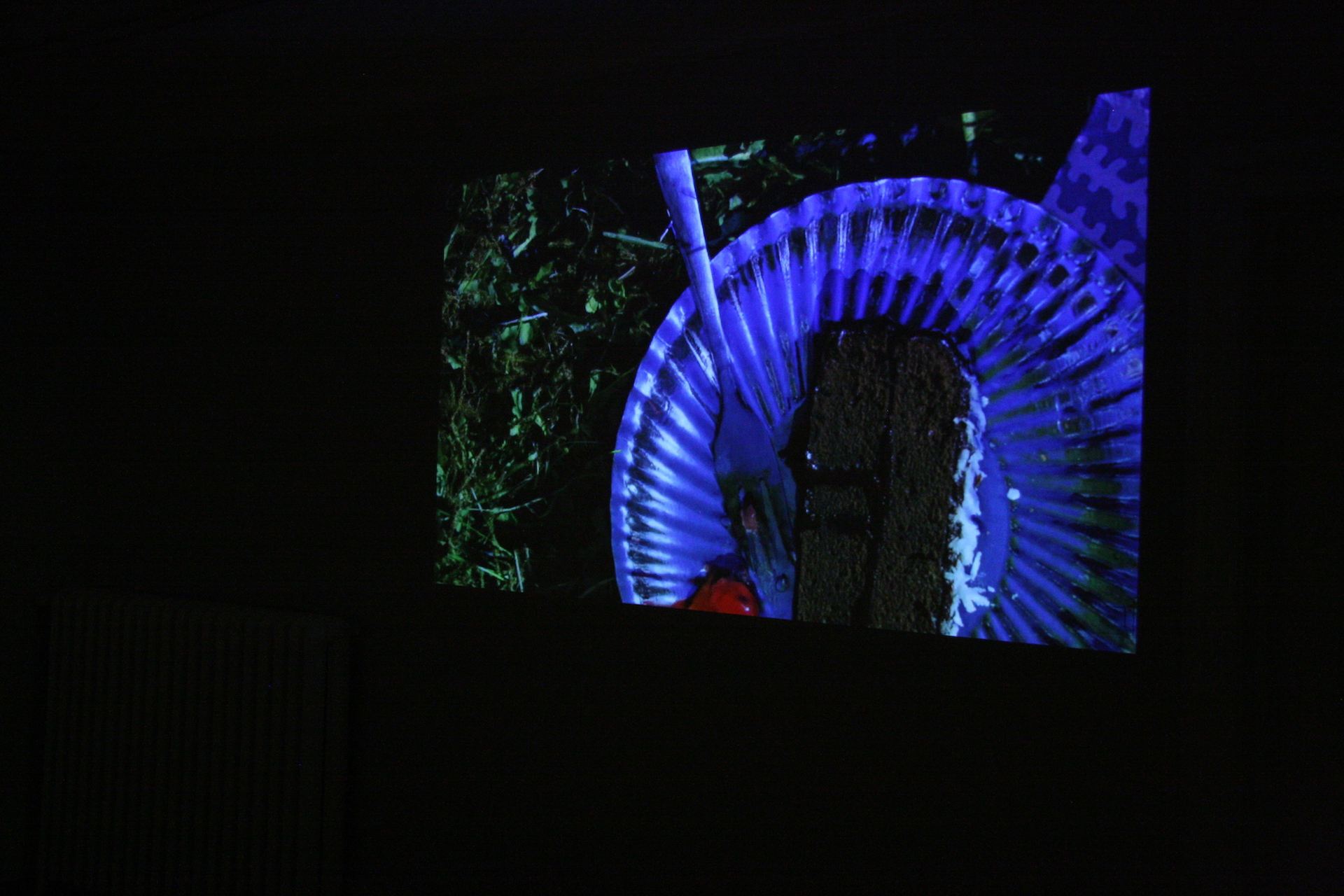

Three larger scale tunnel drawings take up the main gallery; drawn in detail by hand in pen. A mesmerizing tunnel leading us to an abyss of white, we are drawn inside, pulled into the center, tethered still in the gallery space. Crawling creatures, a sky sparkling with red and green and yellow electricity. A planet with a halo of multicolored human shoes, dates and whisper of lines of movement. Geometric forms surround and tumble out from the tunnels, leading to a mysterious other dimension. There is something ominous about them, and also inspiring, in the intricacies of detail. Styrmir’s landscapes are tethered in reality, and yet open up a portal, but to where? Another galaxy, A parallel alternate reality, perhaps? Styrmir explains to me this fascination with the portal:

“I am a hip hop artist. I used to b-boy. I’ve made a rap album in collaboration with a posse of gorgeous artists. My drawings are marinated by the tons of graffiti I used to do. I still draw with the same tools that I used for graffiti. For many years the vandal in me has been sleeping. Today I am more into the world of comics and storytelling with images. I love patching old thoughts with new and mixing mediums into an artistic omelette. In the Thirteenth Month I have drawings that I first made five years ago in black and white. These are portals that I originally drew via my first impressions of Warsaw, where I used to live. For the show I decided to give the portals a facelift by applying a new dimension of colour. And so I recycled them. The freedom of recycling is true to the hip hop nature.”

These five smaller black and white drawings are placed together, containing motifs based in the human. These graphic drawings are just one element of Styrmir’s multidisciplinary practice, as he describes to me:

“Different disciplines are like different days of weather. I find it ideal to switch between activities depending on my emotional state. This way I can be an artist at all times. When I’m feeling blue I can sit down and draw or write a poem. When I wanna dance I make a performance. When I need to move my ass a sculpture is a perfect physical exercise. I feel the personality traits of introversion and extroversion within me. In my experience the introvert mixes well with the making of handicraft as well as writing. The extrovert makes for a good storyteller, singer and dancer. There are so many brilliant outputs in contemporary art. We are the luckiest of cultural workers.”

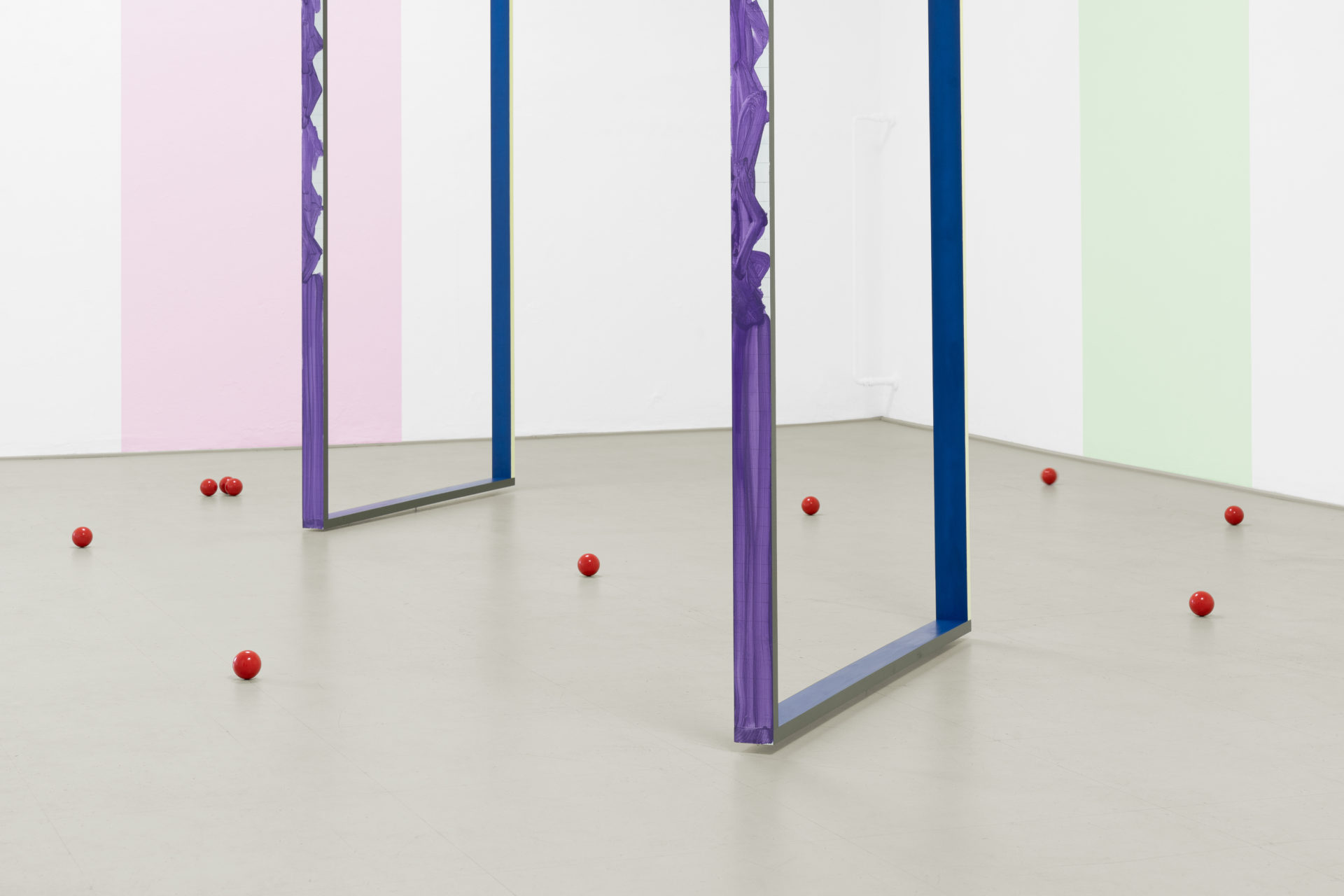

Switching between these different activities, there are also important elements of sculpture, performance, and breaking the fourth wall in Styrmir’s The Thirteenth Month. In one form, green sculptures of flying birds are propped up on a magnetic structure. The sculptures are plastic and abstract, flying in space in static motion. At the opening, viewers were allowed to touch and interact with them, making their shadows echo and shadow further out the boundaries of the gallery’s floors and walls. Here Styrmir critically and comically breaks an inscribed rule within the white cube phenomenon: do not touch. Similarly, an odd sculptural staff with a mirror is propped on the wall; guests can pick it up and see their reflection behind them. It is humorous and performative in a uniquely casual way that makes us question why these modes of behavior within our social art world are inscribed in us to begin with.

“I am used to being a performer in front of people. I love doing that, especially when extroversion levels are high. I feel great without the fourth wall. Things can go beautifully right or wrong without it. But I know it is demanding for the visitor to not have the fourth wall. Without the fourth wall people cannot snooze and eat popcorn. It keeps them on their toes. For The Thirteenth Month I wanted to continue the performance practice without being a performer or director myself. So I planted objects in the show with the hope that guests would meddle with them. I look at them as tools to activate the exhibition guest’s imagination.”

In the middle is a metal sculpture – guests were invited to try and take it apart, to solve the puzzle. Just this simple action created an atmosphere of comedy and lightness, breaking the often stiff, sterile, veering towards snobbish nature of many art openings.

“The puzzle was one of the exhibition tools – a performance. Many gave it a go and tried to solve the riddle. Even philosophers and astrophysicists. They were sweating and blushing from trying to crack the challenge without any luck. Eventually a young cool person, by the name of Uggi, came along and solved the problem in a matter of seconds. He received a standing ovation from the exhibition crowd. Ingibjörg gave him the finest bottle of white wine as an award. Well done Uggi!”

In these ways The Thirteenth Month is a then questioning of human nature – why do we follow our ascribed societal rules and patterns? In the face of the vastness of the cosmos, portals to other dimensions, alternate universes somewhere beyond, these norms are bleakly arbitrary. Strymir pushes us to rethink the purpose and functioning of these almost sacralized behaviors of the white cube gallery space.

“The art world is indeed a high brow place that mostly seduces intellectuals. Many people who are not workers in art feel unsure if everyone is invited to openings and art shows. Of course everyone is invited to art but looking from outside there is this air of exclusivity. People tend to think that contemporary art is something to be understood when it is merely there to tickle your feelings (just like all the other art forms). Art spaces are so sterile and there are some etiquettes such as do not touch. Thank God, otherwise our art history would be covered in mold and finger grease. In my exhibition, though, I have objects that are meant to be touched. But this invitation comes from my longing for live work or for an impromptu performance to happen.”

In the vastness of a cosmic reality, Styrmir questions these ascribed behaviors, high brow nature, exclusivity, etiquette, standing quietly in awe, etc. How can we interact with art in a way that is more playful? Like Styrmir ponders, “Death. Science. Near-death. Animalia. Life.” – There is a whole cosmos out there, and how banal are our art world interactions, in relation to all of this? Perhaps his exhibition, The Thirteenth Month, is a lesson to be learned; not to take ourselves quite so seriously in the face of art.

Daría Sól Andrews

Photos: Courtesy of BERG Contemporary