Allt á sama tíma í Hafnarborg

Allt á sama tíma í Hafnarborg

Á efri hæð Hafnarborgar í Hafnarfirði hefur opnað samsýning sjö ungra myndlistarmanna. Þau eru Auður Lóa Guðnadóttir, Baldvin Einarsson, Bára Bjarnadóttir, Rúnar Örn Marinósson, Sigrún Gyða Sveinsdóttir, Steingrímur Gauti Ingólfsson og Valgerður Sigurðardóttir. Sýningarstjórar eru Andrea Arnarsdóttir og Starkaður Sigurðarson. Sýningin heitir Allt á sama tíma og samanstendur af listamönnum sem allir eru staðsettir á mikilvægu þroskastigi og er sýningin í Hafnarborg innlit í næstu skref þeirra. Sýningin stendur yfir til 20. Október 2019.

Bergur: Hvernig kristallaðist hugmyndin á bakvið þessa sýningu fyrir ykkur?

Starkaður: Við höfum unnið saman áður, sem gekk mjög vel…

Andrea: …Og vorum saman í Listaháskólanum.

S: Við vorum að taka góðan slurk í umsóknarvinnu fyrir rúmlega ári síðan og við settum saman þennan hóp listamanna út frá þeim hugmyndum sem við höfum verið að vinna með sem sýningarstjórar. Okkur fannst áhugavert að setja saman hóp listamanna sem að utan frá eru á svipuðum aldri og með svipaða reynslu, en eru að gera ólíka hluti í listferlum sínum. Listamönnum sýningarinnar var boðið að taka þátt undir þeirri forskrift að sýningin væri ákveðinn þröskuldur yfir það sem yrði næsta skref í listferlum þeirra. Það er klassísk spurning að spurja listnema „hvað mundi gerast ef þú tækir þetta lengra?“ og okkur fannst mikilvægt að skapa nákvæmlega það tækifæri fyrir fólk sem við höfum fylgst með og séð vinna út frá eitthverri samhangandi þróun í gegnum árin.

A: Peningar spila auðvitað stórt hlutverk í þessu. Við fengum styrk frá Myndlistarsjóði og Hafnarborg er að greiða öllum þátttakendum. Okkur fannst mikilvægt að bjóða listamönnum að þróa verk sín lengra eða að bókstaflega skala hlutina svolítið upp vegna þess að hér höfum við tækifæri til að gera eitthvað innan um rótgróna stofnun þar sem sýning sem þessi er möguleg í framkvæmd. Með rýminu sem Hafnarborg er opnast nýjir möguleikar, það er meira pláss, tæknileg aðstoð og laun sem við og listamennirnir fáum.

S: …og áhorfendahópurinn líka! Við fundum strax fyrir því að Hafnarborg á sér marga fastagesti og áhugavert að sjá hvað við getum lært bæði af þeim áhorfendahóp sem og starfsfólki hvað varðar starfsemi safnsins og þeirra væntinga til okkar.

B: Ég fæ á tilfinninguna að þetta sé eins og endur-útskriftarsýning og er gott að sjá fólk sem maður hefur fylgst með í lengri tíma blómstra í sal Hafnarborgar. Hver eru mikilvægustu skrefin, að ykkar mati, í að setja saman svona sýningu, þar sem listamenn eru hvattir til að skala upp eða gera eitthvað sem þau mundu t.d. ekki geta gert í t.d. listamannareknum rýmum?

S: Upphafspunkturinn okkar var að fá að hugsa stærra og við buðum þessum hópi inn með þeirri forsendu. Fyrir okkur og listamennina er sýningin stórt tækifæri og okkur finnst það vera áhugaverður tímapunktur í sjálfu sér. Hvað gerir listamaðurinn við það? Verður verkið um það að gera stærra verk? Eða sérðu það sem leið til að hugsa hvað næsta skref í þínu ferli er? Okkur fannst áhugavert að vinna með hugmyndina um næstu skref hvers og eins, og vinna aðeins með þær væntingar og þrár sem tengjast því frjálslyndi sem listsköpun er í dag. Við sáum strax fyrir okkur að hver listamaður mundi takast á við þetta á mjög ólíka vegu, en við vissum líka að þau mundu grípa tækifærið og gera sem mest úr því.

A: Í byrjun var örlítill kvíði um að einhver mundi gera eitthvað alveg óútreiknanlegt flopp út frá þeirri forskrift að gera stærra! Að sú pressa mundi taka yfir allan hópinn svo úr yrði eitthvað algjört rugl og ekkert tengt fyrri verkum þeirra sem eru að taka þátt. Blessunarlega tóku þau öll við þessari áskorun, ef svo má segja, með meiri yfirvegun en það og mætti segja að hér höfum við rökrétt framhald af því ferli sem nú þegar hefur verið í þróun hjá hverjum og einum listamanni.

B: Gott dæmi gæti talist vera það sem Auður Lóa er að gera. Hún sagði mér frá Grísku styttunum sem skúlptúrarnir vísa í og þann misskilning að þær hafi alltaf verið einungis hvítur marmari… að þær voru í raun málaðar á skrautlegan hátt og snýr þannig upp á þessa dýrkun á hvítleika í vestrænni menningarsögu! Mér fannst strax áhugavert hvernig verkin hér eru ekki einungis stærri, heldur hér er þróun tekin að vinna lengra aftur í tímann, að endurskoða söguna í gegnum þá fagurfræði sem Auður hefur unnið með áður.

S: Það hefur verið mjög gaman að fylgjast með Auði þróa þessi stærri verk vegna þess að aðferðin á bakvið þau er sú sama og með fyrri verk. Eldri pappamassaverkin bera líka með sér þessa ríkulegu, glansandi postúlínáferð að utan en þegar haldið er á þeim kemst maður að því að eru þetta mjög létt stykki! Fyrir þessa innsetningu voru nokkur praktísk atriði sem við þurftum að vinna að saman vegna þess að stytturnar hér eru svo miklu stærri og þurfa meira umstang í kringum sig. Það sem virðist vera á yfirborðinu í verkum Auðar verður að svo mikilvægum upphafspunkt fyrir okkur sem skoða verkin. Líkt og grísku stytturnar er ákveðin ráðgáta í gangi, að útlitið blekkir það sem er að innan líkt og það sem hefur mást út í gegnum aldirnar. Hverju tökum við eins og það er og hvernig getum við endurhugsað þá sögu sem ímyndir vestrænnar menningar hafa skilið eftir sig? Að gera eitthvað stærra hefur þannig orðið að dýpri rannsókn í menningarsögu okkar og að bókstaflegri upp-skölun í ferli Auðar. Frá byrjun sáum við hlutverk okkar, sem sýningarstjórar, vera að planta þessum fræjum í ferli listamannanna, að búa til þessa pælingu og sjá hvað er hægt að gera út frá henni.

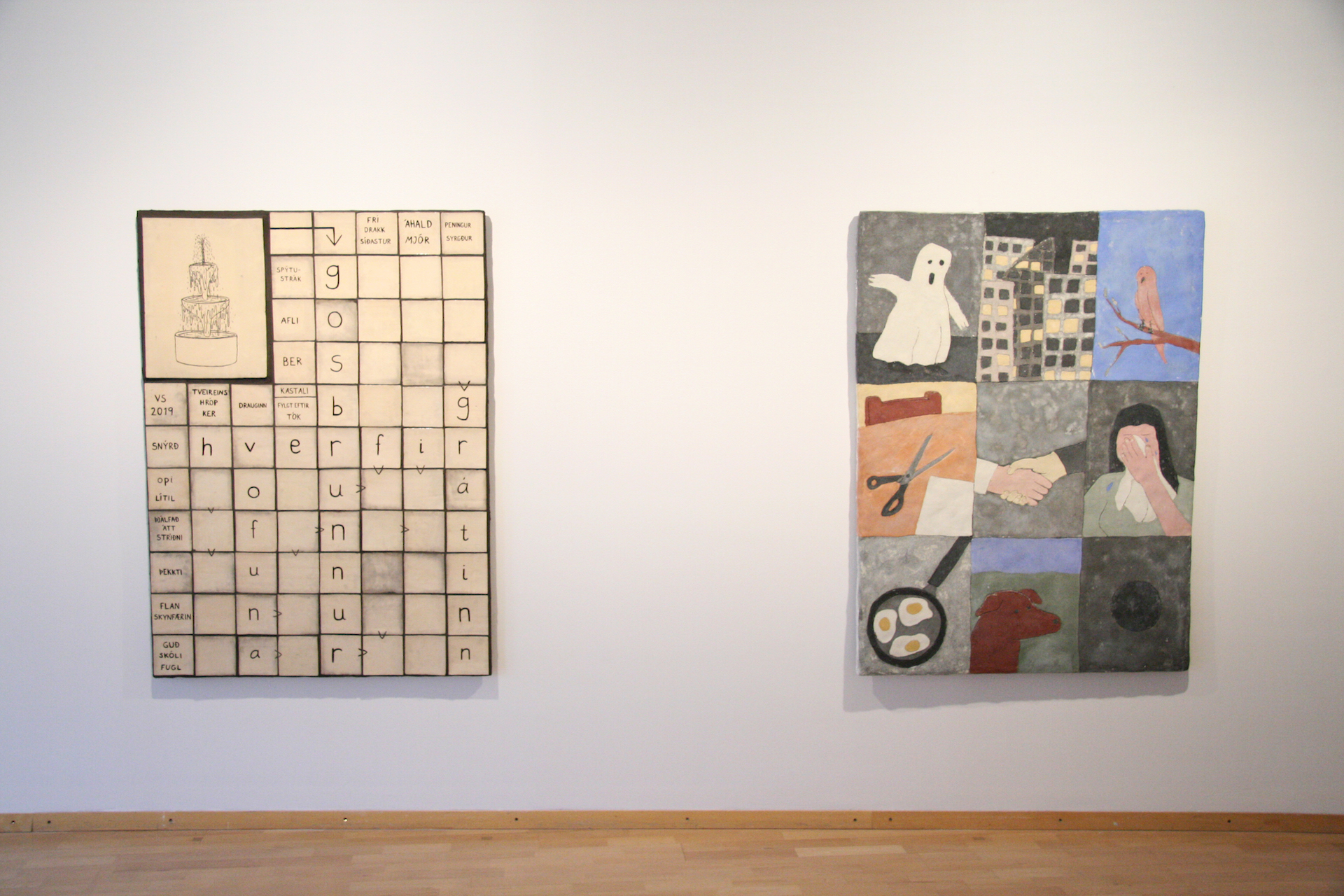

Installation view: Auður Lóa Guðnadóttir, Marmari, 2019, akríl á pappamassa. Steingrímur Gauti Ingólfsson, Án titils, 2019, olía á striga

Installation view: Auður Lóa Guðnadóttir, Marmari, 2019, akríl á pappamassa. Steingrímur Gauti Ingólfsson, Án titils, 2019, olía á striga

B: …Og síðan er þessi hugmynd um frelsi, og þann endalausa brunn af auðlindum sem listamenn hafa. Við vitum ekki hversu lengi þetta verður allt til staðar, en viðhorfið virðist ennþá vera að myndlist getur orðið til úr hverju sem er. Mér finnst mjög áhugavert að þú nefndir þennan kvíða áðan, vegna þess að margar skriftir þessa dagana setja sjálfræði og kvíða hlið við hlið. Þegar þú ert sjálfstætt starfandi myndlistamaðurinn þá er 99% af kvíðanum þínum þetta frelsi sem þú hefur hvað varðar spurninguna hvað gerist næst?

S: Frelsið er tálsýn og við vitum það alveg. Okkur fannst áhugavert að taka þetta frelsi og skapa samhengi utan um það, að setja það í kassa. Það sem listamönnum finnst vera frelsi er eitthvað allt annað en það sem sýningargestir skilja sem frelsi. Og hvernig getur frelsi passað saman á þennan hátt? Er það nóg að það sé bara hópur af einhverju fólki? Okkur fannst áhugavert að stýra þessu opna fyrirbæri í áttina að einni mynd af íslenskri samtímalistalist. Áherslan er þannig á það hvað hver og einn gerir við frelsið, frekar en að vera sýning um frelsi sem viðfangsefni t.d.

Okkur fannst mikilvægt að sjá hvað fólk gerir við þetta hugtak og hvernig hugmyndir um frelsi og næstu skref geta birst á mismunandi hátt innan um verkferli hvers og eins. Steingrímur Gauti gerir t.d. abstrakt málverk og vinnur útfrá þeirri innsýn sem hann hefur í þann heim. Fyrir honum er stórt skref að fara úr akrýl í olíu. En hér eru verk eftir hann úr blöndu af báðu, ásamt virkri teikningu og collage tækni. Hann þekkir þá sögulegu frásögn sem hann er að taka þátt í og tekur ákvarðanir um næstu skref út frá því, burtséð frá því sem t.d. Rúnar Örn væri að gera. Fyrir Rúnari gæti stórt skref í hans ferli falist í því að ákveða t.d. hvort að hann ætli að vera í mynd í myndbandsverkinu sínu, eða frá hvaða sjónarhorni þessir fundnu hlutir eru teknir upp?

Hvað telst vera stór skref í þessum fjölbreyttu ferlum listamanna er sá vinkill sem hefur gefið okkur mikil forréttindi sem sýningarstjórar og gefið okkur innsýn í ferlið sem við reynum að tækla á opin hátt. Mér finnst þessi dýnamík áhugaverð að skoða og þá hvernig listamenn í dag hafa stjórn á því að skapa sína eigin valkosti út frá eitthverjum stærri raunveruleika sem þeir búa í. Okkar statement er það að þetta eru allt gildar spurningar, hvort sem þú ert að mála abstrakt eða festa tilvistarlegar vangaveltur á vídeó!

B: Af listamönnunum að dæma er áhersla á vissa leikgleði, en líka á persónulegar narratívur. Hér er meira af efnislegri þróun, sköpun heilabrota sem koma úr hversdagslegri reynslu og ljóðrænunni þar. Það er margt sem bendir til mikró-narratíva, eins og þær aðferðir sem Rúnar Örn beitir til að framleiða sérstök mengi þar sem merking listaverksins er rannsökuð í gegnum tímalínu þess…

S: Þetta eru listamenn sem hafa innan í sér áttavita eða eru nýbúinn að finna vott af þessum áttavita. Þau treysta sér til að „gera svona verk“, eins og þeirra signatúr er kominn í ljós og nú er hann að blómstra. Gott dæmi er Valgerður (Sigurðardóttir), sem virðist hafa einhvern ósýnilegan og frábæran drifkraft sem beinir henni að því næsta, þrátt fyrir að hún þekki ekki lokaútkomuna fyrirfram.

A: Ég get ekki sett fingurinn á hvað það er nákvæmlega, en það er vissulega seigla og viðhorf sem listamennirnir deila. Jákvæð orka og sérþekking á því hvert verkferlið er að leiða þau.

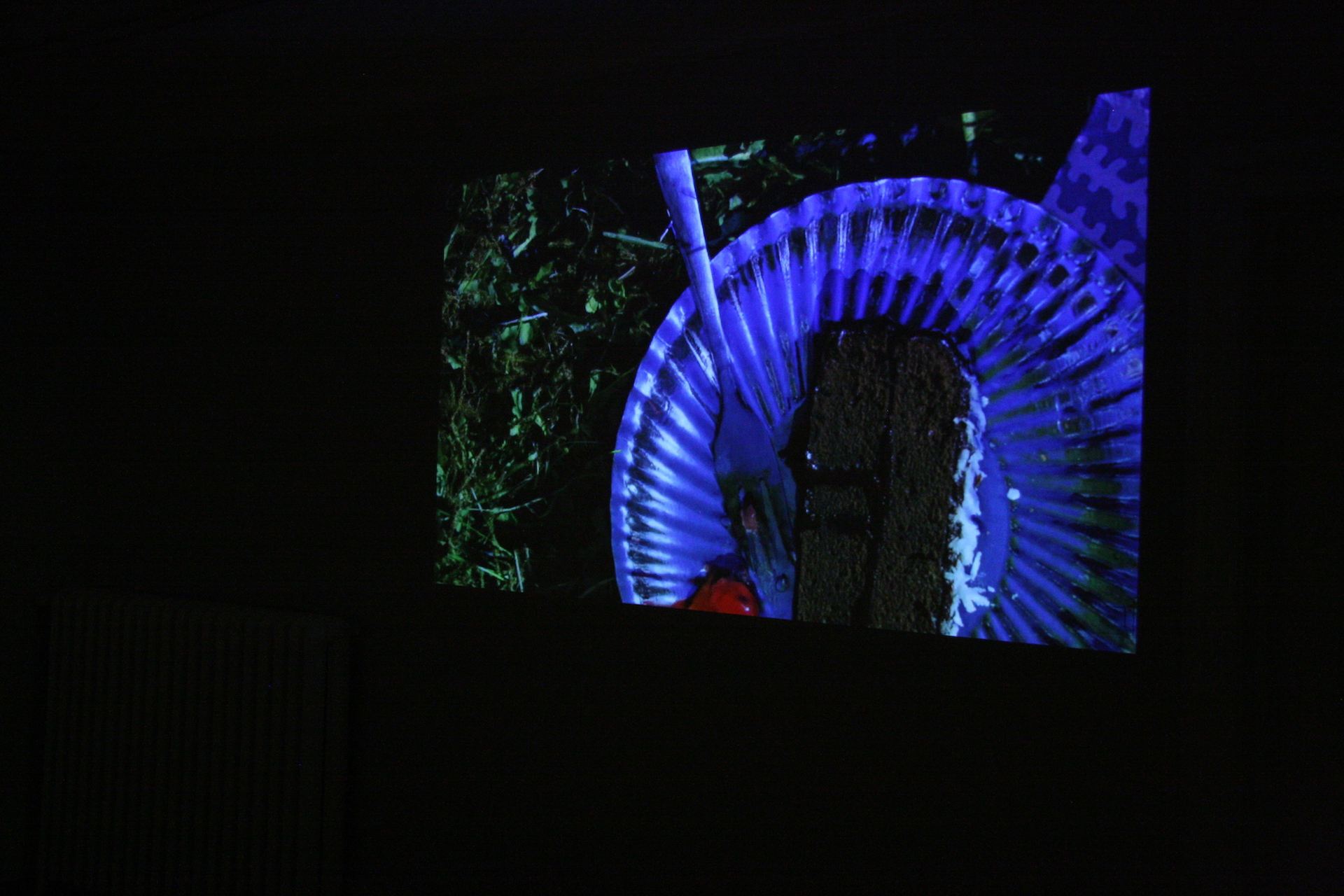

Installation view: Rúnar Örn Marinósson, UH OH, 2019, Video 30 min og Baldvin Einarsson, The Best Things in Life Aren’t Things, 2019, Keramík.

Installation view: Rúnar Örn Marinósson, UH OH, 2019, Video 30 min og Baldvin Einarsson, The Best Things in Life Aren’t Things, 2019, Keramík.

B: Eruð þið líka að vinna með þær væntingar sem listamennirnir hafa til framtíðarinnar?

S: Okkur finnst mikilvægt að gefa þeim tækifæri, þetta er fólk sem á líklega eftir að vera í myndlist allt sitt líf, og við höfum séð mjög sterka þróun í verkferli þeirra í gegnum árin. Ég veit ekki einu sinni hvort þetta sé spurning um væntingar, heldur bara að treysta að það sem komið hefur áður gefur af sér eitthvað sem gefur mynd af listamönnum framtíðarinnar. Þau eru nú þegar listamenn nútímans.

A: Og þau eiga það sameiginlegt að vera að þróa sitt.

S: Maður fattar eitthvernveginn að fólk verður listamenn þegar þau eru bara að gera hvað sem er sett fyrir framan þau að sínu. Við erum öll á þessum stað að við erum að fatta hvað er í gangi, þetta er allt nýtt, og erum að detta í þennan farveg sem fylgir okkur í framtíðina. Við vitum eitthvað, en vitum ekki allt, og það er það sem okkur fannst svo spennandi þáttur í vinnslu sýningarinnar.

B: Hlutirnir eru teknir út frá þessum jákvæða pól án þess að taka það sem er að gerast í kringum þig úr myndinni.

S: Já, þetta er ákveðinn þroski kannski. Fólk veit hvað það er með og notar það til að skilja það sem er að gerast í kringum sig.

B: Markmið ákveðinna listgreina er að gera hlutina af það mikilli hæfni að áhorfendur eru hættir að taka eftir því hversu handlaginn þú ert í í raun og veru. Samanber smíðavinnu eða jafnvel því að leika í bíómyndum. Markmiðið er oft að láta hlutina virðast látlausa á yfirborðinu, svipað og leikari gerir hlutina nógu raunverulega þannig að fólk hættir að taka eftir því að hann er að leika. Ég fæ á tilfinninguna að þetta sé það stig í listferlinu þar sem hlutirnir fá að verða til frá brunni fyrri reynslu og þekkingu á því hvernig eitthvað verður til.

S: Já, maður er hættur að taka eftir hlutnum með stóru spurningarmerki og maður er farinn að sjá miklu skýrar hvernig listaverkið verður til. Eins og með verk Auðar Lóu, þú sérð hlutinn svo mikið, en efnið minna, en um leið og þau vita úr hvaða efni stytturnar eru verður til mjög virk umræða um hvernig hluturinn er búinn til. Það er þetta fyrirhafnarlausa vinnubragð sem hægt er að þjálfa. Sama með Steingrím, þetta eru málverk. Það er eitthvað svona kjarkað í því. Baldvin og Vala sömuleiðis, þau eru orðinn svo þjálfuð í keramíkinu, að þau geta leyft sér að fara þessar leiðir með það.

Valgerður Sigurðardóttir, Vísbendingar, 2019, Steinsteypa, litarefni og Valgerður Sigurðardóttir, Krossgáta, 2019, Keramík.

Valgerður Sigurðardóttir, Vísbendingar, 2019, Steinsteypa, litarefni og Valgerður Sigurðardóttir, Krossgáta, 2019, Keramík.

Installation view: Valgerður Sigurðardóttir, Kona á klósettinu/ Dagblað, 2019, steinsteypa, litarefni, keramík, Valgerður Sigurðardóttir, Vísbendingar, 2019, Steinsteypa, litarefni and Valgerður Sigurðardóttir, Krossgáta, 2019, Keramík.

Installation view: Valgerður Sigurðardóttir, Kona á klósettinu/ Dagblað, 2019, steinsteypa, litarefni, keramík, Valgerður Sigurðardóttir, Vísbendingar, 2019, Steinsteypa, litarefni and Valgerður Sigurðardóttir, Krossgáta, 2019, Keramík.

B: Það er marglaga exposure af efnistökum á sýningunni. Hefðir héðan og þaðan, vídeó, málverk, hljóð… Var mikilvægt fyrir ykkur að sýna þessa flóru og þetta flæði af miðlum?

A: Við vorum að skoða hvernig allir miðlar eru orðnir samþykktir í listum í dag, og okkur langaði að sýna að við erum komin á þann stað í listasögunni að allt er jafnt á sama tíma og við erum að vísa í fortíðina.

S: Það er ekki hægt að gera sýningu sem tekur alla myndlist inn.

A: Þetta er svona fókúsuð en líbó nálgun…

S: …Og við settum mikið í hendur listamannsins á sama tíma. Það er okkar gegnumgangandi sýn sem teymi. Við lögðum upp með það að sýna þessa dýnamík. Við byrjuðum á Steingrími Gauta í raun og veru, og hugsuðum hvað væri öfugt við það sem hann er að gera? Við komumst síðan að því að það eru engar andstæður til lengur, að þetta allt er á sama planinu og gilt sem slíkt. Og með innkomu Hafnarborgar skapaði þetta samansafn verka góðan grunn til að vekja umræðuna um að allar tjáningarleiðir myndlistar séu gildar og að yngri kynslóðin sé sérstaklega að vinna með margvíslega snertifleti sem tengjast þeim. Þetta snýst á vissan hátt um að skrásetja okkar listasögu.

B: …Og gerir atlögu að því að taka miðla-híerarkíu í burtu. Þetta frelsi sýnir líka mjög vel hversu mikil forréttindi það er að vera myndlistarmaður í dag og hversu ríkt starf það er þegar kemur að mögulegum auðlindum, efnum, og viðfangsefnum sem hægt er að fást við. Hvernig sjáið þið ramma þess frelsis sem þið hafið sett upp svona eftir á?

S: Verkin hans Steingríms Gauta eru til í stofum fólks, en hverjir kaupa verk eins og þau sem Rúnar eða Sigrún Gyða framleiddu fyrir sýninguna? Söfnin kaupa meira af innsetningum eða vídeóverkum. Híerarkían kemur alltaf eitthversstaðar inn sérstaklega þegar spurningar um vörslu, geymslu og uppihald koma inn. Það er yfirleitt hlutverk safna að halda utan um það sem passar ekki auðveldlega fyrir í hefðbundnum rýmum eða á sér tilvist í fleiri en einum miðli. Hvað verður um þessi verk eftir sýninguna er ekki undir okkur komið, en þau eru hér samankomin tímabundið. Það er það sem skiptir okkur líka máli hvað varðar þráð og narratívu sýningarinnar. Kannski er þetta sýning sem meikar ekkert sens! Við vitum það aldrei, og svona initíatívur koma alltaf meira í ljós þegar litið er til baka.

Sigrún Gyða Sveinsdóttir, Draw me like one of your french girls, 2019, Video.

Sigrún Gyða Sveinsdóttir, Draw me like one of your french girls, 2019, Video.

Bára Bjarnadóttir, Heitasti dagur ársins , 2019, Video 10:23. Söngur: Anna Dúna Halldórsdóttir.

Bára Bjarnadóttir, Heitasti dagur ársins , 2019, Video 10:23. Söngur: Anna Dúna Halldórsdóttir.

B: Sýningarlandslagið í Reykjavík er líka aðeins að breytast. Ég fæ á tilfinninguna að sýningarnar sem hafa verið að koma upp hér spurja hvort það sé hægt að eignast yfirsýn yfir höfuð? Það er mjög mikið verið að skoða hvaða myndir listamenn eru að framleiða í dag og hvort það sé samhengi á milli þeirra. Við erum kannski ekki á þeim tímapunkti að geta dæmt heildarmyndina.

S: Hlutverk skrifta um myndlist og krítík er allt önnur og hlutverk listaverka breytist sömuleiðis með samfélagslegum breytingum. Það er módernísk hugmynd að það er mögulegt að hafa yfirsýn. Við erum ennþá að skapa yfirlitssýningar og þær verða áfram framleiddar, en hvað gerum við með „okkar listasögu“ núna? Þurfum við yfirsýn? Við fáum á tilfinninguna að fólk taki á móti hverju verki eins og það er, frekar en hvaða master-narratívu það er að taka þátt í. Allt má, og allt er gilt, hvað gerum við með það? Og hvaða mynd skapar það? Frelsi myndlistarinnar í dag er þannig að gefa áhorfendum miklu meira frelsi líka.

Það er bæði orðin minni krafa og meiri krafa um það að sýningar sem þessar séu að taka bókstaflegan þátt í samfélagsumræðunni. Bæði er leyft. En þá kemur siðferðisleg spurning inn í samtalið, sem kemur kannski inn núna á næstu árum. Í dag er oft verið að setja hluti saman án þess að bera þá saman eða gera úr þeim hetjur og and-hetjur. Það er allt í lagi að gera ekki öllum til geðs. Spurningin er, þegar allt er gilt, hvað er hægt að fá útúr því? og listamenn virðast vera að fá allt annað út úr vinnunni sinni í dag en fyrir 10 árum.

Það er einhver sem sagði, man ekki alveg hver, að maður getur ekki túlkað með einhverri sannfæringu nema tuttugu ár aftur í tímann. Að það sem verður til í dag er ekki endurspeglun endilega af því sem gerðist mest nýlega heldur í besta falli það sem gerðist fyrir um tuttugu árum. Við túlkum alltaf aftur í tímann og það sem er að gerast í dag er ekki skilgreint í rauntíma. Með óvissunni er líka mikil spenna, að geta ekki svarað spurningum um það hvað sé að gerast.

Hvert skref í ferli listamanna er pólitískt skref, og myndlist er alltaf hápólítísk þannig. Mér finnst listamennirnir hérna vera vissir um hver þau eru og að þau séu tilbúinn að taka á móti öllu því sem snýst um samfélagið í dag. Ég hef það á tilfinningunni að verkin hér eru nógu sterk til þess að takast á við þessar nútíma baráttur.

Bergur Thomas Anderson

Photo Credit: Hólmar Hólm Guðjónsson.

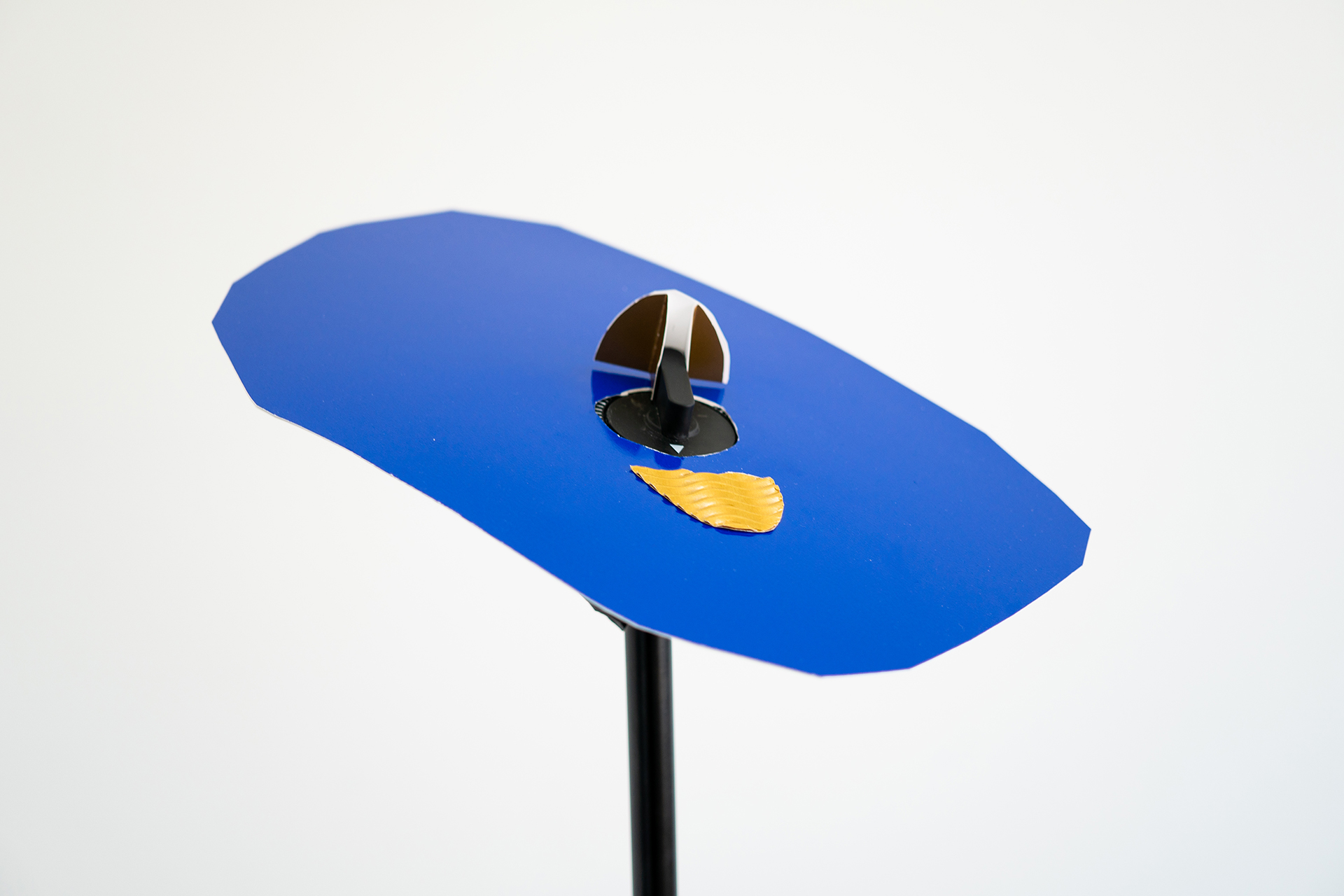

Cover picture: Baldvin Einarsson, The Best Things in Life Aren’t Things, 2019, Keramík.