Iceland’s New Neighbors At The Venice Biennale

Iceland’s New Neighbors At The Venice Biennale

For the first time since Iceland’s involvement in La Biennale di Venezia (or the Venice Biennale), the Icelandic Pavillion is located in the Arsenale: one of the fair’s main exhibition spaces. This move is significant for the pavilion, which was first located in the Finnish pavilion from 1984-2005, and has since been independently placed around the city of Venice. Not only will this new location increase viewership by an estimated 20 times more than recent years, but it quite literally places the pavilion in dialogue with the main curated exhibition and its neighboring pavilions.

Now that Iceland finds its new home in the Arsenale, I (Amanda Poorvu) had a conversation with fellow Icelandic intern Hrafnkell Tumi Georgsson and the next-door Latvian and Maltese Pavillions to get to know our new surroundings and gain some insight into their exhibitions. I spoke to interns Agnese Trušele and Eva Hamudajeva from the Latvian Pavillion, and Lisa Hirth and Nicole Borg from the Maltese Pavillion.

Latvia:

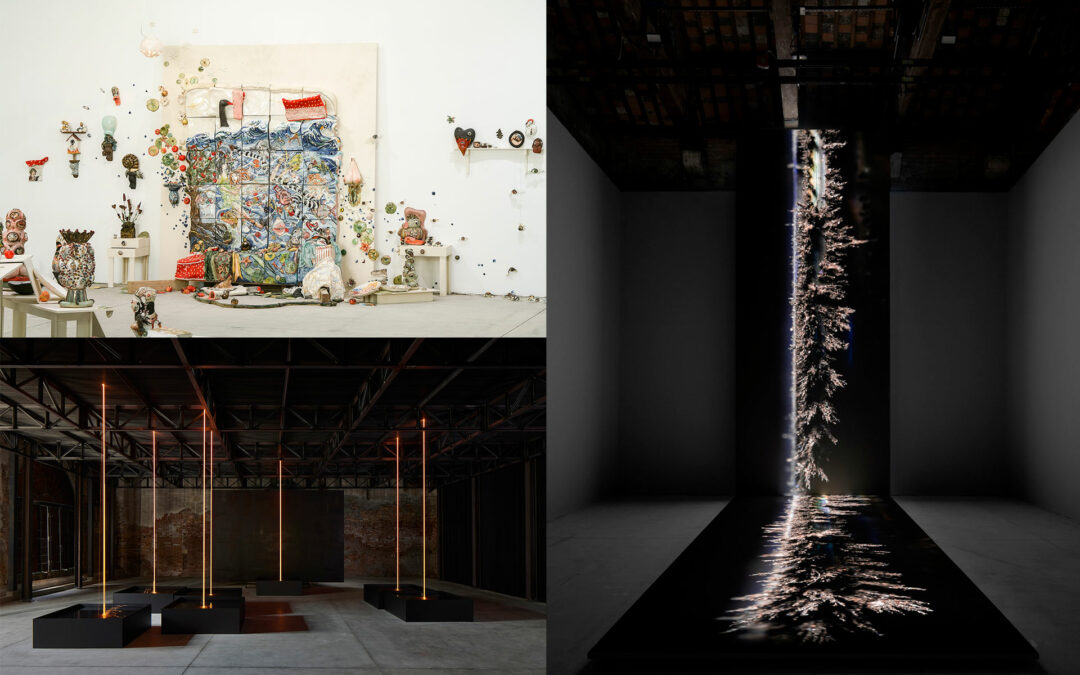

Photographer: Aleksejs Beļeckis © Courtesy: Skuja Braden (Ingūna Skuja and Melissa D. Braden) ©

Photographer: Aleksejs Beļeckis © Courtesy: Skuja Braden (Ingūna Skuja and Melissa D. Braden) ©

How long has your country held a pavilion in the Arsenale?

Agnese: Latvia has had its own national pavilion since 1999, but in 2013 it started exhibiting permanently in the Arsenale. It started in a smaller space and in 2015 moved to this space.

Who is exhibiting this year? And who curated it?

Eva: The artists of Selling Water By The River are a female couple/duo SkujaBraden, commissioned by Solvita Krese and curated by Solvita Krese and Andra Silapētere.

How did this exhibition come about?

Agnese: There is a competition where the ministry of culture chooses the winners, and then someone else organizes it. In this case, it is organized by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, which also organized it in the 56th edition of the Biennale.

Eva: The exhibition is a multilayered installation that maps the mental, physical, and spiritual areas within the artists’ home. In the exhibition, home is echoed by images in porcelain, a material that Skuja Braden has mastered superbly. Their porcelain comes to life in everyday objects, fountains, bendy hoses, male and female physiques, and nature.

The Biennale is one of the largest art exhibitions in the world, and there is so much to see. In three words, how would you describe the exhibition to entice a visitor to stop by?

Eva: Perspective, Humanity, Dream.

Agnese: Humorous, Human, Mainīgs (a Latvian word that means “everything changes,” you can use this word to talk about the weather, for example)

What are some of the themes in the exhibition that you feel are relevant to the world today?

Agnese: Feminism, Sexism, Patriarchy, and political issues in the world…in some ways, the spiritual and physical symbiosis of bodies, because of the altar and the vanity room. I feel like the main focus of the pavilion is the bed: people tend to want to know what goes on in the bedroom. The bedroom is also an important space because you are born in it, you rest in it, you are sick in it, you create life in it, and you even die in it. The title Selling Water By The River is a book by a Zen Buddhist about how we don’t need to sell or buy something that is already there.

Eva: “White man” power.

If you had to pick a (second) favorite pavilion in the Arsenale besides your own, which pavilion would you pick?

Eva: The main exhibition, specifically the Ruth Asawa, Jes Fan, Marguerite Humeau, Tetsumi Kudo artworks.

Agnese: I think Mexico is interesting, because of the background of how people donated money. The concept is interesting.

Malta:

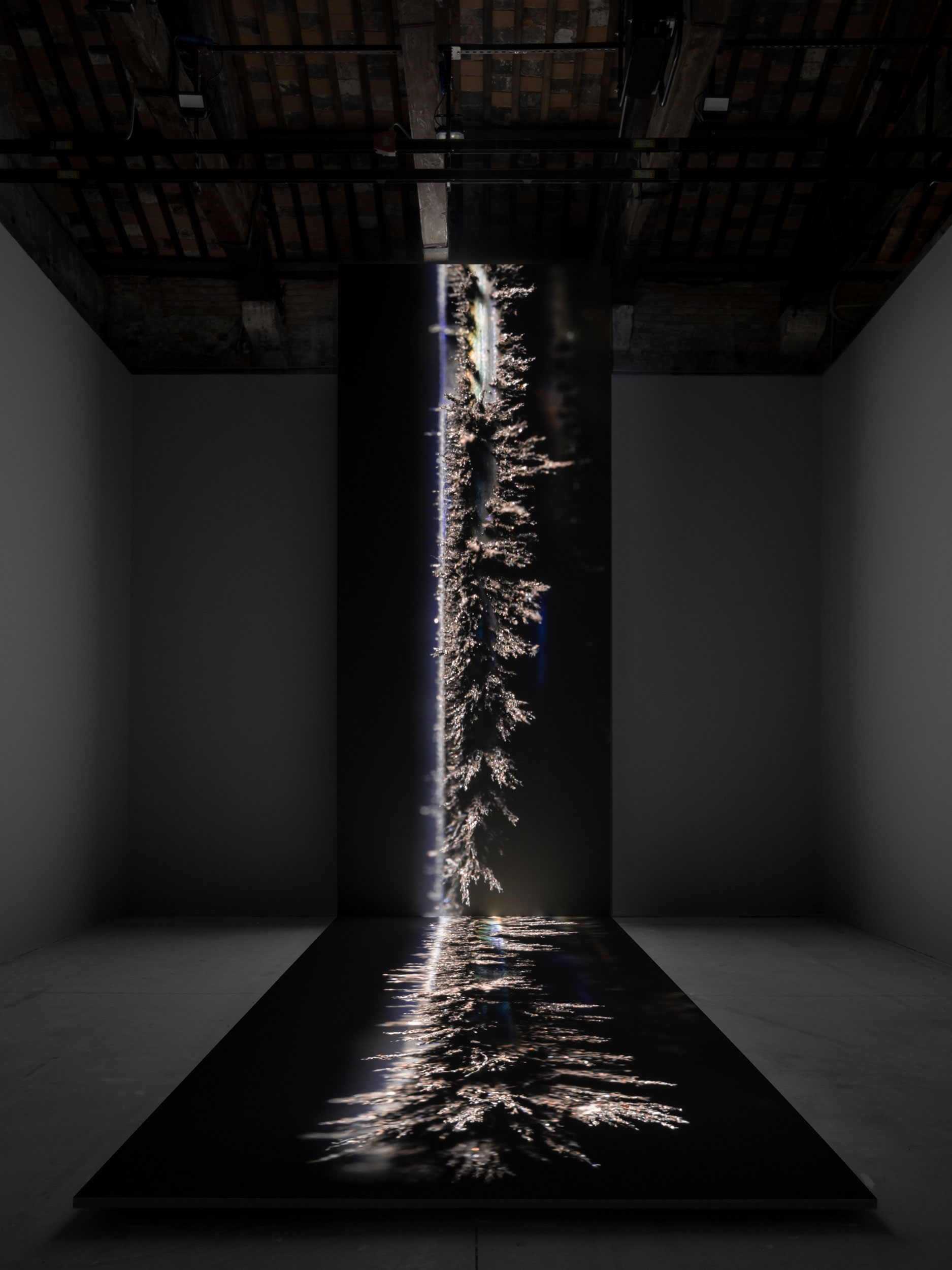

Photographer: Agostino Osio

Photographer: Agostino Osio

How long has your country held a pavilion in the Arsenale?

Amanda: Through my research, I found that Malta has had a long absence from the Biennale, only participating in several group exhibitions in 1958 and 1999. Its pavilion wasn’t included until 2017, making this the third pavilion it’s held.

Who is exhibiting this year? And who curated it?

Lisa: Arcangelo Sassolino from Italy, and Brian Schembri and Giuseppe Schembri Bonaci from Malta are the artists of Diplomazija Astuta, and the two curators are Keith Sciberras from Malta and Jeffrey Uslip from the U.S.

How did this exhibition come about?

Lisa: The artwork started before the biennale, around 3 years ago. Arcangelo had the idea for a single drop of fire, and he brought the idea to the curators. Originally, they wanted to put this single drop of steel under the painting, The Beheading of Saint John by Caravaggio in Malta. Logistically it didn’t work out, but they realized that the room of the Arsenale was a similar size to the oratory so they decided to take the aura of the painting and transpose it from Malta to here, in a contemporary art space.

The Biennale is one of the largest art exhibitions in the world, and there is so much to see. In three words, how would you describe the exhibition to entice a visitor to stop by?

Nicole: Captivating, Unpredictable, Encourages cultural Relativism.

Lisa: Tenebrous, Show-stopping, Mysterious

What are some of the themes in the exhibition that you feel are relevant to the world today?

Lisa: It is based on recent political events in Malta because the title means “cunning diplomacy.” There was a case a few years ago where a well-known journalist got murdered, and a lot of corruption is coming to light. The main theme of the artwork is injustice and how if we don’t put an end to cunning diplomacy, the cycle of injustice will continue. This is what Malta is currently facing now.

Nicole: The repetition of injustice, particularly to Malta, and the theme of political injustice relative to Malta in recent years can be applied to a variety of cultural contexts. However, for Malta, it’s interesting to observe the theme of patriotism towards Caravaggio and Maltese art, as well as how patriotism is sometimes used as a rejection of the significance of Caravaggio’s role in Maltese art throughout history

If you had to pick a (second) favorite pavilion in the Arsenale besides your own, which pavilion would you pick?

Nicole: Mexico

Lisa: The Latvian one, because it’s very chaotic but controlled, and it is very pleasing to look at. I like that it makes people uncomfortable.

Iceland:

Sigurður Guðjónsson, Installation view: Perpetual Motion, Icelandic Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition -– La Biennale di Venezia, 2022, Courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary, Photo: Ugo Carmeni

Sigurður Guðjónsson, Installation view: Perpetual Motion, Icelandic Pavilion, 59th International Art Exhibition -– La Biennale di Venezia, 2022, Courtesy of the artist and BERG Contemporary, Photo: Ugo Carmeni

How long has your country held a pavilion in the Arsenale?

Hrafnkell: This is the first year that Iceland has been in Arsenale.

Who is exhibiting this year? And who curated it?

Amanda: The Iceland Pavillion features the work Perpetual Motion by Sigurður Guðjónsson, curated by Mónica Bello, Curator & Head of Arts at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Geneva)

How did this exhibition come about?

Hrafnkell: It was announced in 2019 that Sigurður would be this year’s artist for Iceland. He was chosen by a committee that picked him out of a group of artists that were nominated for the show.

The Biennale is one of the largest art exhibitions in the world, and there is so much to see. In three words, how would you describe the exhibition to entice a visitor to stop by?

Amanda: Expansive, Meditative, Anachronistic

Hrafnkell: Dark hypnotic rumble!

What are some of the themes in the exhibition that you feel are relevant to the world today?

Hrafnkell: I think at first glance I thought it was very different from the works you see in Arsenale before you come to the Icelandic Pavilion. You arrive here shortly after going through the Milk of Dreams exhibition, that is full of surreal and personal works. This work feels more distant, you are looking at metallic dust moving. For me, it felt very scientific and straightforward but then it pulls you in and a lot of questions arise about what you are actually seeing. It feels at the same time very simple but also like there is a lot of manipulation going on, but I can never really put my finger on exactly what, maybe there is none. It made me appreciate this detailed way of observing and think about how we observe – which patterns we see and which patterns we project onto what we see.

Amanda: Although it is not required for the national pavilions at the Venice Biennale to relate thematically to the main exhibition, Sigurður Guðjónsson’s work, Perpetual Motion, in the Icelandic pavilion does share a common theme with The Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani. In her own words, Alemani describes the focus of the exhibition and its relevance as, “the representation of bodies and their metamorphoses; the relationship between individuals and technologies; and the connection between bodies and the Earth.” It is this relationship that we have with technology that not only grounds Perpetual Motion but remains a driving force in Sigurður’s practice as a whole.

If you had to pick a (second) favorite pavilion in the Arsenale besides your own, which pavilion would you pick?

Hrafnkell: I really like the Malta one, they are also next door so I go there a lot. Italia is also one of my favourites.

Amanda: The Dutch pavilion.

Overall, it was an exciting first year at the Arsenale and we are delighted to be placed next to such interesting and inspiring neighbors in the space. Thank you to all the participating interns who spoke with me. On to the next Biennale!

Amanda Poorvu

Christoph Büchel’s Barca Nostra by the sandwich bar in the Arsenale.

Christoph Büchel’s Barca Nostra by the sandwich bar in the Arsenale. The Swiss sculptor Carol Bove was this years’ discovery of the journalist. Her sculptures are a twist of the clean lines of modernistic sculptures where she uses the aesthetic and semiotics of the dent, the bend, the pull, the roll, the squeeze and other types of transformative actions as her own language. The color palette creates the illusion that the steel she uses is really soft and flexible material and the sculptures demand that ones’ body, eyes and mind glide around the work.

The Swiss sculptor Carol Bove was this years’ discovery of the journalist. Her sculptures are a twist of the clean lines of modernistic sculptures where she uses the aesthetic and semiotics of the dent, the bend, the pull, the roll, the squeeze and other types of transformative actions as her own language. The color palette creates the illusion that the steel she uses is really soft and flexible material and the sculptures demand that ones’ body, eyes and mind glide around the work. Nabuqi is a young Chinese artist that also uses steel in her work but in a different way. She uses found objects and creates stages where she plays with simulations in an artistic research on how we connect to our environment. In the work Destination from 2018 she uses an advertising billboard with a photoshopped picture of a paradise decorated with palm trees but also with fake plants in a work that plays with the interplay of fantasy and simulations. Promises are given without the opportunity to be able to fulfil them.

Nabuqi is a young Chinese artist that also uses steel in her work but in a different way. She uses found objects and creates stages where she plays with simulations in an artistic research on how we connect to our environment. In the work Destination from 2018 she uses an advertising billboard with a photoshopped picture of a paradise decorated with palm trees but also with fake plants in a work that plays with the interplay of fantasy and simulations. Promises are given without the opportunity to be able to fulfil them.

The Murano glass sculpture of the Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga in the Arsenale was an interesting investigation into a local raw material that played an important part in the colonial trade history. It reminded the journalist of Otobong’s work about the glimmering mica material at the Berlin Biennale in 2014. Mica is the material that made the church towers of Europe glow in the sun while in her home country it made the ground glitter. As the journalist has been seeing a lot of installation and sculptural work of Otobong in the last few years it was a pleasure to see Otobong’s works drawn on paper in the Giardini part. Otobong’s contribution won a special jury prize together with the work of Mexican artist Teresa Margolles.

The Murano glass sculpture of the Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga in the Arsenale was an interesting investigation into a local raw material that played an important part in the colonial trade history. It reminded the journalist of Otobong’s work about the glimmering mica material at the Berlin Biennale in 2014. Mica is the material that made the church towers of Europe glow in the sun while in her home country it made the ground glitter. As the journalist has been seeing a lot of installation and sculptural work of Otobong in the last few years it was a pleasure to see Otobong’s works drawn on paper in the Giardini part. Otobong’s contribution won a special jury prize together with the work of Mexican artist Teresa Margolles. The Silver Lion went to a young artist the jury considers very promising:

The Silver Lion went to a young artist the jury considers very promising: