A! performance festival: in conversation with director Hlynur Hallsson

A! performance festival: in conversation with director Hlynur Hallsson

In its 5th iteration, A! Performance Festival returned this year to galvanise Akureyri’s art scene. Showcasing the interplay between visual arts and performance, the annual four-day festival welcomed a variety of established and up-and-coming artists onto the Northern stage. I meet with Director of the Akureyri Art Museum, Hlynur Hallsson and two participating artists, Florence Lam and Sunna Svavarsdóttir, to discuss experimental variety, open structure and the element of surprise.

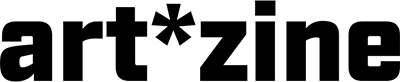

Haraldur Jónsson (IS), Þröng/Thron, Hof Culture house, Akureyri (12/10/19) Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

Haraldur Jónsson (IS), Þröng/Thron, Hof Culture house, Akureyri (12/10/19) Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

Claire-Julia: Can you tell us about the origins of A! Performance Festival, what was the catalyst for this project?

Hlynur: It all started 5 years ago, when we thought that Akureyri needed a performance festival, in that moment, we also realised that there was just no performance festival in Iceland at all. Ragnheidur Skúladóttir was the Program director of Theatre and Performance Making at the Icelandic Academy of Arts. There she had been engaged in the field of experimental theatre, so she was also interested in this dialogue between performance and the theatrics of visual art. Together with Bjarni Jónsson, her husband, they had been running Lókal performing arts festival in Reykjavik for some years before, so the groundworks were already in place.

Akureyri also has a history on performance, for example, there was Rauða Húsið (Red House) built in the 1980s which was a very influential venue. It platformed artist Magnús Pálsson for example and became a place for lots of artists to showcase unusual exhibitions and productions. At the same time, there was also a couple of local Akureyri artists who had been focusing on performance, for example Örn Ingi Gíslason and Anna Richardsdóttir. Based off this history, we decided it would be a good idea to found this festival, mixing younger artists with more experienced ones, as well as local and international artists. From there it developed organically, this mixture was very well accepted and I hope it continues to be.

C-J: With over eighteen artists involved in this year’s productions, each offering distinct performances, were there any standouts for you?

H: I liked very much the performances from Tales Frey (Brazil); Estar a Par and Be (on) you which featured a duo mirror act and a dynamic performance wearing connected shoes, I thought that was really amazing. Heart Song from Florence Lam (HK), who directed a mic towards her heart, was also a fantastic addition and a captivating performance on stage. Another standout for me was the endurance project by Icelandic art group ‘Kaktus’, who were in character during the whole festival. They started on Thursday evening and went on till Sunday morning, to be observed acting through a window wearing dog masks. Passers by on the street could stop to watch the dogs doing activities such as having a party, sleeping or eating breakfast. We welcomed a great variety this year; another example was the performance from Iris Stefanía and Hljómsveitin Eva (Iceland) on female masturbation. The first showing on Saturday afternoon was only for women and the second in the evening was open to everyone, it was a very interesting and feministic conversation. There were lots of standouts for me, although I am always happy with the festival, I think this year was particularly fruitful in terms of variety.

Kaktus group (IS), Spangoland, Mjólkurbúðin / Visual artist project space, Akureyri. (10-13/10/19) Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

Kaktus group (IS), Spangoland, Mjólkurbúðin / Visual artist project space, Akureyri. (10-13/10/19) Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

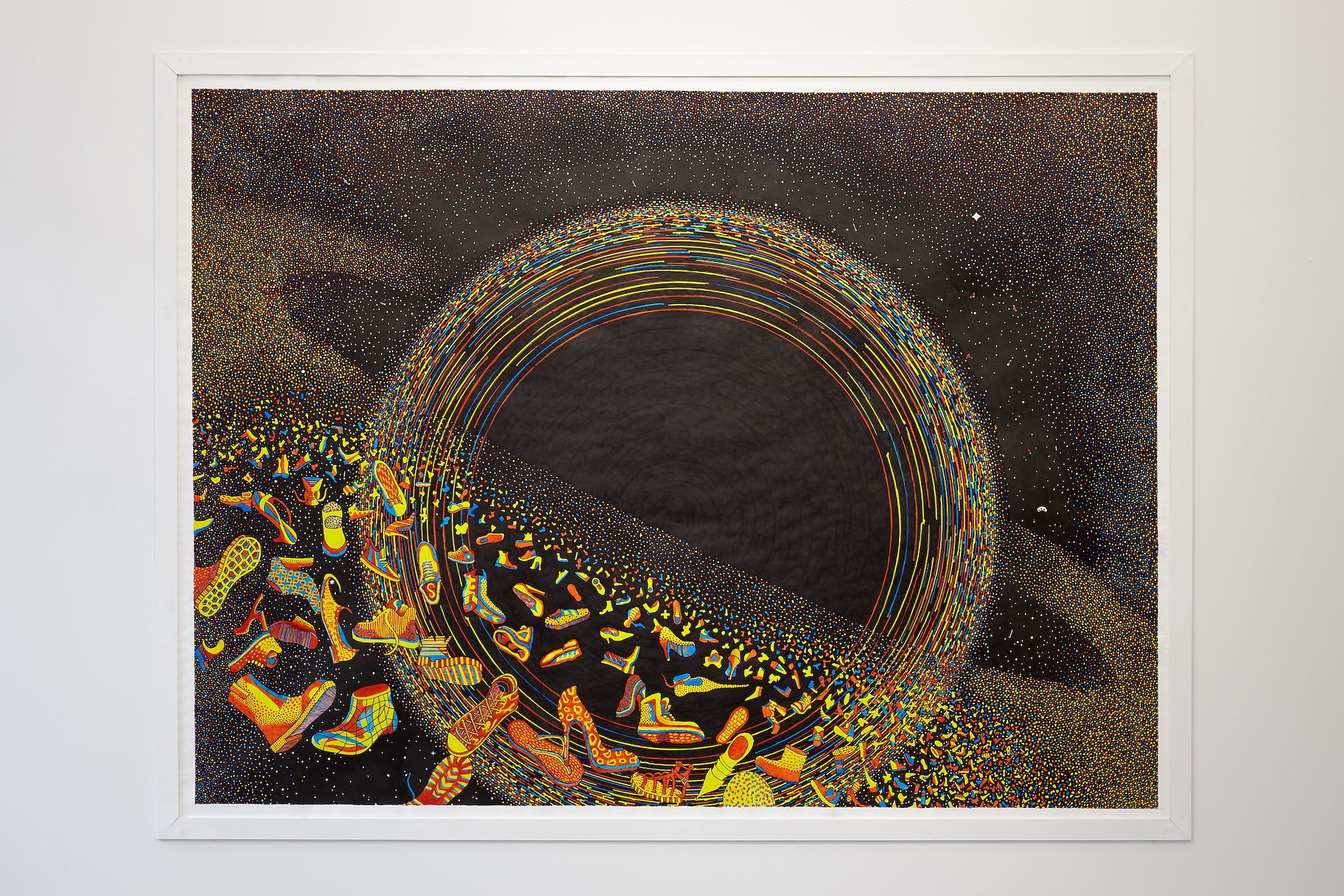

Dustin Harvey (CA), Less Plus More, Akureyri Art Museum. (11/10/19). Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

Dustin Harvey (CA), Less Plus More, Akureyri Art Museum. (11/10/19). Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

C-J: Has your own art practice, particularly the installation and performances aspect, influenced your relationship with this festival?

H: In my time working as an artist and in my curatorial practice, I always wanted to include others in my works. When I had an exhibition I would often invite other artists, sometimes up to twenty, to take part too and that was usually well accepted. Over time, it became part of my work to facilitate meetings, conversations and projects between different people. For example, I ran a space for two years in Hanover, Germany, where I aimed to bring together and exhibit the collaborative work of two artists who did not know each other prior. Of course, this led to very interesting outcomes, both artists being influenced by the other’s output meant it was always a great experience. I have been involved in organising a lot of cooperative events in this manner and I think that undoubtedly influences my approach to A! Performance Festival.

C-J: This festival is in cooperation with many cultural institutions, for example the Culture society, the theatre centres and the Reykjavik Dance Festival. As such a big collaborative enterprise, what role did the Akureyri Art Museum play in its realisation?

H: The Akureyri Art Museum is the centre part of this organisation, but we are beginning to divide it more between the Art Museum and Akureyri theatre. Then it’s always great to have collaborations from others, both from grassroots organisations and the Visual Arts Centre in Reykjavik. We are also in collaboration with the students of Verkmenntaskólinn (Akureyri Comprehensive College), who come in to assist the festival artists as part of their curriculum, that is great to see. In addition, we have the video festival Heim (Home) is held in the city at the same time and that has been a very interesting combination. For the first time this year we also had an open call, from which we selected five candidates. That of course allowed us to broaden our horizon for the festival, it’s always great to have ideas coming in from new people.

C-J: As Director, how would you characterise the aims of this festival?

H: The aim for us is to showcase variety, and to display the full extent of what performance can be. A work can end in two minutes or it can last for sixty-eight hours, it can be a performance for just one person or it can be hundreds of people taking part, there are no limitations. It is like opening a window to the audience here in Akureyri, to display what is happening in performance art elsewhere, but also to platform what artists are doing here in Iceland. The festival is free, there is no admission for the shows as we wanted it to be open for everyone. The programme is also designed so that the audiences can move from one viewing to the next. We hope that amongst the variety there will be something for all, and perhaps there will be something surprising in between that you discover for yourself.

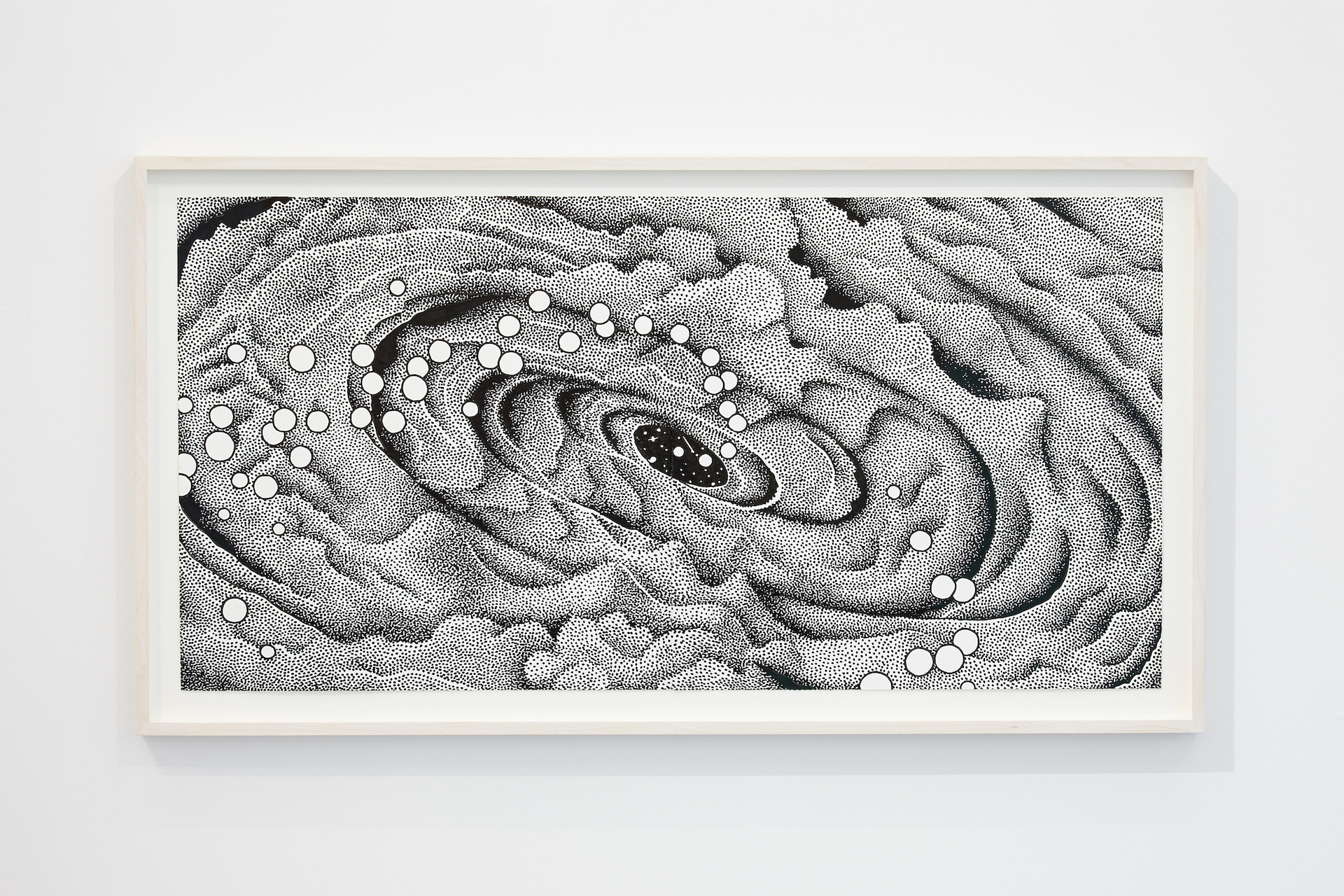

Snorri Ásmundsson (IS), Sana Ba Lana / Master Hilarion, Hof Culture house, Akureyri. (12/10/19) Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

Snorri Ásmundsson (IS), Sana Ba Lana / Master Hilarion, Hof Culture house, Akureyri. (12/10/19) Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

From inside this years artistic cohort, Florence Lam (b.1992, HK) gives an insight into her experiences performing in the festival with her piece Heart Song. She explains, “This was one of my very first live performance pieces created in 2014. I am sitting still, as still as a sculpture. I am pointing a mic towards my heart. From the speakers, audiences will hear my voice explaining what the performance is about. The performance is an act of exploration, thinking about what performance, sculpture, art and myself performing as a ‘living being’ signify. I created this work based on my main interests in wonder and magic; by connecting the intimate action of listening to my heartbeat with the spoken text in my own voice, the performance created an illusion of my heart speaking directly into the microphone in human language. Like a human being performing with a special power.”

Against this backdrop, Akureyri-born artist Sunna Svavarsdóttir (1992, IS), who presented her work Invitation Inside a Stone as part of the Off-Venue programme, comments on the sense of wonder and dynamism this festival injects into the Northern community. Svavarsdóttir, whose work brings forth the subtleties of sensual experiences, recounts an anecdote of her performance.“Everyone became so serious when immersed in the work, the atmosphere changed. Even a runner slowed to a jog when moving past us, as if exposed to a funeral procession. It was fascinating to witness participants and onlookers’ reactions.” In interview, the artist remarked upon the “open and diverse model” of this year’s iteration, acknowledging the efforts made by the organisers to draw in a variety of participants. “This festival does a lot to the community here in Akureyri,” the local artist tells me, “there was such an exciting mix of national and international artists, I predict ‘A!’ will continue to evolve in this respect.”

Florence Lam, Heart Song, Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

Florence Lam, Heart Song, Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

Sunna Svavarsdóttir, Invitation Inside a Stone. Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

Sunna Svavarsdóttir, Invitation Inside a Stone. Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.

For Director Hlynur Hallsson, this festival holds an exciting future; one which he hopes will continue to captivate audiences, enrich Akureyri’s art scene and stimulate conversation around what performance art can be.“I think that’s one of the interesting things about performance, especially in the nature of festivals, is that you never know exactly what will happen” he tells me.“There will always be something unexpected and the surprise-effect keeps it interesting. However, I think that we can always do better and receive a wider variety of performances. The goal is not necessarily to bring in big names from the art world, but rather to foster this mixture within the artistic cohort that I hope will become an enduring part of the festival. Another aim is to continue to build the off-venue programme, so that even artists who are not directly included in the festival will be able to take part in side projects whilst still being connected to the event. I think that is important to cultivate. I also hope that by showcasing these performances every year, it will become even more accepted amongst audiences and that it will hold an established position on the Icelandic art calendar.”

Amongst the ever-evolving facets of this festival, one salient characteristic can be predicted for certain; the breadth of variety on show. Make the leap to Akureyri’s Festival A! next year, performative surprises to all tastes will await you.

Claire-Julia Hill

A! Performance Festival will next take place in Akureyri between the 1st and 4th of October 2020.

Cover picture: The Northern Assembly (N), Nordting, Hof Culture house, Akureyri. (12/10/19) Photo curtesy of Daníel Starrason.