The Artist Platforming the Subtle: Meet Sunna Svavarsdóttir

The Artist Platforming the Subtle: Meet Sunna Svavarsdóttir

“when tying your shoelaces place one foot in front of the other

when wishing for wet feet pour water inside your boots,

when a pause is needed put your head inside a stone…”

These lines, elegant and playful, grant insight into the creative output of Icelandic artist Sunna Svavarsdóttir (b.1992), whose work offers a master-class in how to experience the subtle sensations in life. Having graduated in 2019 from the Royal Academy of Art & Royal Conservatory in The Hague, she has since developed a unique, multidisciplinary practice which opens a dialogue on how we navigate the world with our senses, and shines a spotlight on the small moments that often fall by the wayside. On the cusp of the Icelandic winter, I meet with Svavarsdòttir to discuss her development as a performer, the incorporation of kinesthetic installations in her practice and how harnessing salt can season the senses.

Claire-Julia: What steps brought you to become an artist?

Sunna: At twenty years old, I had no idea what I wanted to become. I had always associated art with painting, sculpture and drawing and those were not things I had been doing much of myself. Living in Reykjavík at the time, I enrolled myself in courses at Myndlistarskólinn í Reykjavík and from there I began to research online and found the ArtScience course in the Hague, which looked like a good fit. Opting for an interdisciplinary course there may have seemed like a very specific choice, but indeed, I chose it because it was so unspecific; it had a very open curriculum and we were granted a lot of freedom in what we wanted to learn. It was challenging, especially in the beginning because you are also discovering what you want to create yourself, but that’s why I pursued it. From the moment I started my studies there, I knew I wanted to become an artist. I am also lucky to have parents that really support me and my decisions, this helped me get to where I am today.

C-J: How would you characterise your artwork?

S: I often work with installations that invite audience participation. Because what I set up is so simple, it needs the viewer to activate it in order for it to become complete; so in that respect, my art could also be seen as a type of interactive performance. I’m interested in offering viewers a platform to experience subtle sensations, as I believe they are often taken for granted. I’ve experimented with incorporating elements like smell, touch and weight in my work, as I find it fascinating when something so small, like a bit of pepper or a few extra kilos, can give you such a powerful experience. You always expect the big things to have the greatest effect, but I like when the little things surprise you. For example, there’s a common experience we’ve all had, when you first place a helmet on your head and it takes your body sometime to adjust to the new weight. This transition period, when adding or removing a weight to our head, is so short, only lasting five-seconds or so. But these types of sensations; the little ones that are often forgotten, that’s what I’m hoping to bring out in my work.

C-J: You didn’t consider your work as a performance until quite recently, what made you come to that realisation?

S: Because my work is an ongoing process and I’m inviting people into very subtle experiences, I was always afraid that by calling it a performance, people would need a clear beginning and an end point, whereas I wanted my work to be seen more as a continuous process. For me, the performance is the audience and I look at myself more as the facilitator. I also learnt a lot from my time with the ArtScience Interfaculty, where I had the chance to take part in theatre workshops. They were very intense classes, sometimes lasting up to eight weeks long, but also very magical, as they left such a strong connection between the people involved. The performances we created during these times were often experimental. For example, in one instance we were trying to engineer machines from our own bodies. These workshops had a big influence on the way I work; they taught me how to get your audience with you and it also gave me a lot of courage. They showed me that performance could be many things at once, and that in a way, so was my work.

C-J: One of your early projects, ‘Make a Mountain’ captures the start of using audience participation in your work. How did it come about?

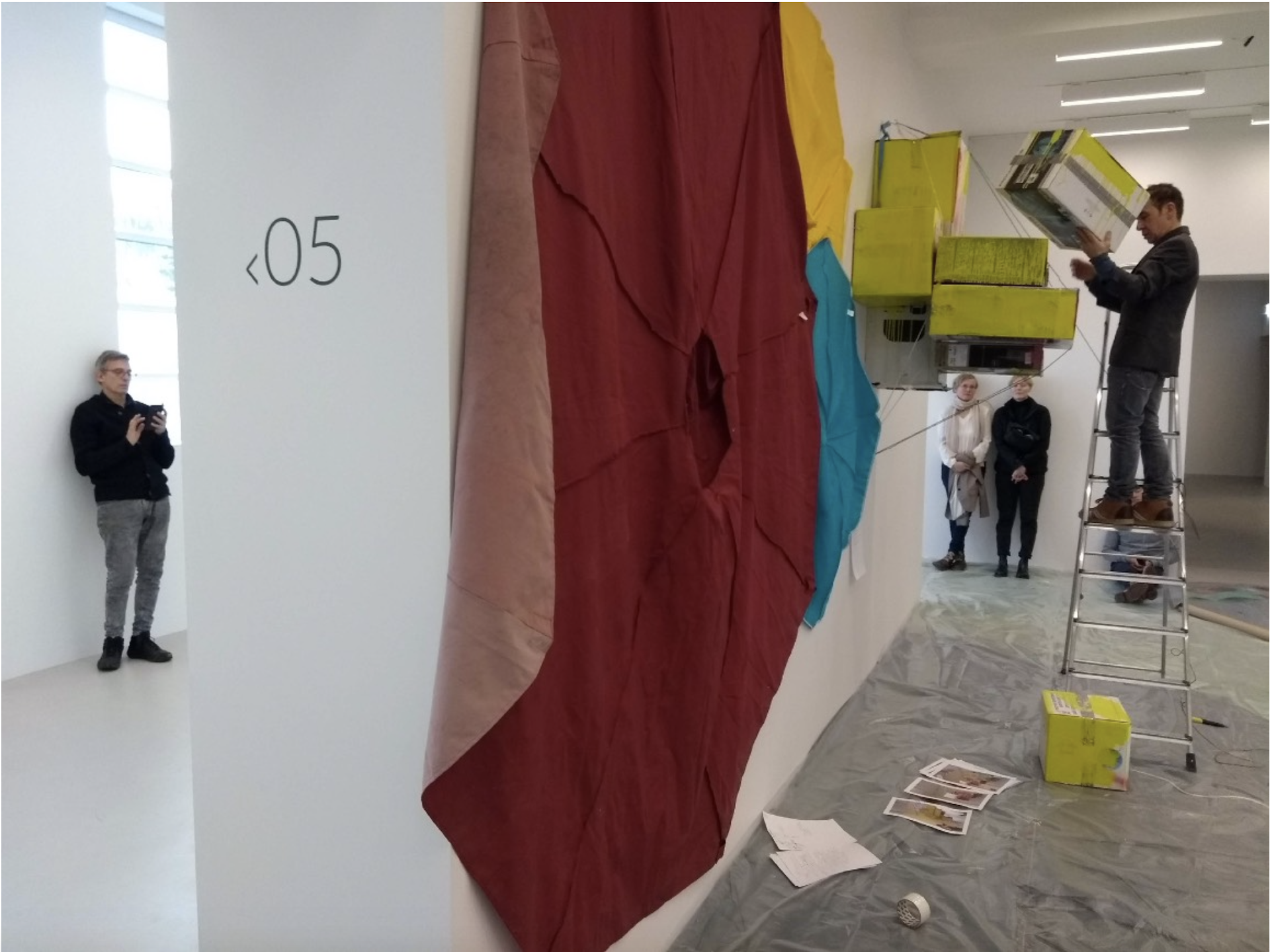

S: It began when I was doing some tests whilst I was artist in residency. It was an enormous space, so we had a lot of room to play with and to create something on a large-scale. At first, I just experimented by myself in the studio and I came across this idea. I remember thinking, ”Now this is an interesting experience, but how can I introduce it to other people?” I realised, when you have such a simple thing to present, that it is more engaging to guide the visitors into the work and encourage audience participation, rather than just have instructions. The title, “Make a Mountain” also implies an action which is explained when a person is standing underneath it. This ethos was the initial starting point for later projects I developed, in particular my work „27.2″.

Sunna Svavarsdóttir, Make a Mountain, Eindhoven (“noititiper, De Fabriek”)(2018) Photography: Georgina Kosmatou.

Sunna Svavarsdóttir, Make a Mountain, Eindhoven (“noititiper, De Fabriek”)(2018) Photography: Georgina Kosmatou.

C-J: In your ’27.2,’ we see you move to explore kinaesthetic experiences triggered by weight. Where did this idea develop from?

S: I was doing research for another project and I stumbled on an article discussing the effects of looking down at your phone and the strain it places on the head. From there, I started researching all these bizarre devices which are sold on the internet to train your head to be in the correct position. These devices are incredibly funny and sculptural, some of them even look like art pieces in their own right. From there, I began the process of collecting them all together. Looking through all these contraptions trying to realign the body using weight, I was reminded of the strange sensation of having a pressure, like a sand-bag, placed on your head. After that, I did some experiments in the studio using bags which weighed 8 kilograms each. I soon realised that not that much pressure is needed to trigger the strange sensation, and that closing the eyes multiplied the intensity ten-fold. From there, the project developed naturally.

C-J: Some participants reported ‘27.2′ as like being on the bow of a ship, some described it to be like floating weightlessly. As the facilitator, was it interesting for you to observe different audience reaction?

S: I found it fascinating to watch the way people interacted with my installation. Most described it as weightless and liberating, a few also found it slightly uncomfortable, which I think is interesting in equal measure. It’s a one on one experience, with myself lowering the weight onto their head, and for some people, the idea of being watched is off-putting. However, for others it came naturally to stand underneath and they would relax immediately, that was beautiful to see. But what I found most interesting was when participants fell in between these two reactions, into something more subtle. The moment when the audience’s hesitation subsides and they step into the unfamiliar space, that is exactly the subtle which fascinates me. Some people also say no, and that’s fine too and a part of it. Instead, they take on the role of observer, contributing to the interplay between the performance and the performer.

Sunna Svavarsdóttir, weigh salt, The Hague. (Royal Academy of Art) (2020) Photography: Jesus Canuto

Sunna Svavarsdóttir, weigh salt, The Hague. (Royal Academy of Art) (2020) Photography: Jesus Canuto

Sunna Svavarsdóttir, the artist readjusting weight for performative installation weigh salt, The Hague, (Royal Academy of Art) (2020) Photographer: Frederik Klanberg.

Sunna Svavarsdóttir, the artist readjusting weight for performative installation weigh salt, The Hague, (Royal Academy of Art) (2020) Photographer: Frederik Klanberg.

Sunna Svavarsdóttir, 27.2 kg, The Hague. (‘Opening Credits’, Grey Space in the Middle) (2018) Photography: Jesus Canuto.

Sunna Svavarsdóttir, 27.2 kg, The Hague. (‘Opening Credits’, Grey Space in the Middle) (2018) Photography: Jesus Canuto.

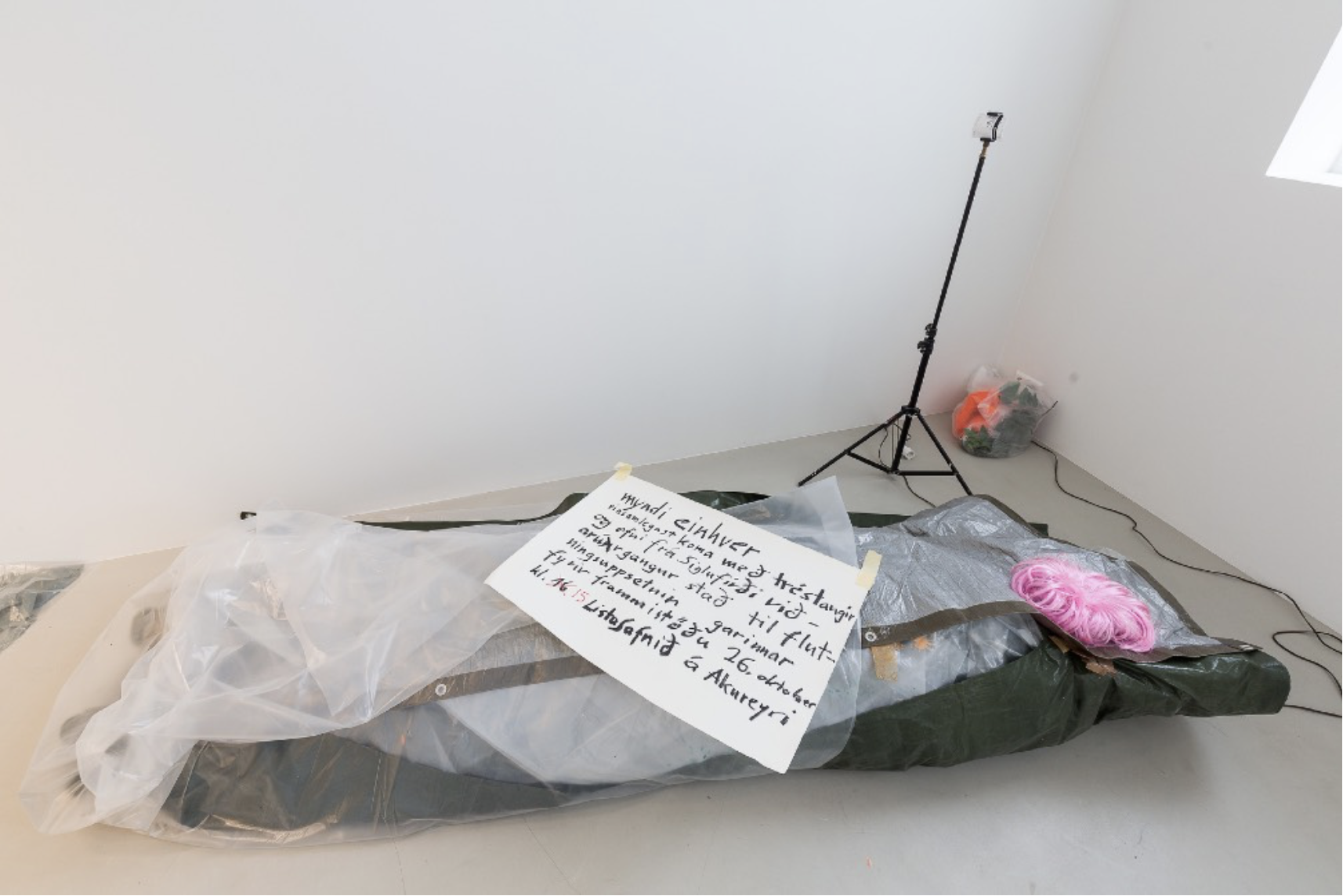

C-J: You mentioned your choice of salt in this installation, why did you choose this material in particular?

S: When I first began this project, I was using sand from the Hague laced with small amounts of pepper. It worked well initially, and the subtle hint of pepper added to the experience I was trying to create. But, after a while it posed problems as the fine grains would leak through the bags and fall into the eyes. On a practical level, the swap to salt, as a coarser material, eliminated this problem, whilst also bringing interesting poetic connotations to my project. We used 150 kilograms of salt in the end, we needed a lot more than I expected. I said to my coach at the time that it was enough.“Now, is not the time to compromise” he laughed. It was a hot summer during the show and we were working in a beautiful space with large glass windows. On clear days, the sun would beam through and it became humid very quickly. The high ratio of salt to air in the room created this interesting holistic experience, the atmosphere became thick and dry, the skin began to tingle and you could taste salt in your mouth long after you’d left the work. It was a first for me to be incorporating the sense of taste into my art, which made this project, and the salty aftertaste it left, all the more interesting for me.

C-J: Are there any artists that have had a particular influence on your own work?

S: During my studies I did a workshop with the art historian of the lower senses Caro Verbeek (b. 1980, NL), there she discussed many concepts that have stayed with me; for example the condition of reversal synesthesia and the linguistics surrounding smell. For me, this links in with the idea that more subtle sensations are taken for granted, which has really influenced the way I work. Another is the artist Maki Ueda (b.1974, Japan) who explores the olfactory sense in her art. Her ethos focuses on smell as the new media, and uses scents to strengthen her practice and spark the imagination. The performances staged by contemporary artist Ragnar Kjartansson (b.1976, Iceland) have also had a significant effect on my own work. Engaging with multiple mediums, Kjartansson uses performance as the central tenant of his art, drawing together cultural references and connecting them through pathos and humour. The haptic qualities in the work of Hrafnhildur Arnardóttir (b.1969, Iceland), otherwise known as Shoplifter, have also offered interesting parallels to my installations, which have equally, yet distinctly, placed emphasis on sensorial stimuli.

Claire-Julia Hill

Svavarsdóttir has participated in two group shows since January 2020, including ‘Jong Talent‘ in the Netherlands (Jan18-Mar 8, 2020), and ‘The New Current’ (4-9 Feb, 2020), a non-profit organisation which exhibited during the Rotterdam Art Week. She is currently on show at Museum Jan Cunen; Haagse School x Haagse Nieuwe (Feb 8-June 1, 2020). There, Svavarsdóttir’s work can be experienced along with a new piece as part of her weight series ‘Weight Costume’ which is a wearable sculpture. For more information on her work please visit: http://www.sunnasvavars.com

Cover picture: Sunna Svavarsdóttir, 27.2 kg, The Hague (‘Opening Credits’, Grey Space in the Middle) (2018) Photography: Jesus Canuto