On future and fortune

On future and fortune

A detailed model of a house in ruins lays on the floor on a pile of black sand, the miniature interior design furniture clashes with the wreckage scattered around the building. The roof, as well as one of the four walls, has collapsed, nonetheless two design metal chairs are placed on the second floor close to a window, a corner where to relax and enjoy the view. A white corridor with a futuristic design resembling that of Star Trek spacecrafts extends outside of the house, goes around it and leads to the inside: a fancy entrance which offers an alternative to stepping through the detritus of the torn down wall and access the house with another perspective.

The floor of the gallery is demarcated by black lines, a sports field of a game which rules are unknown to us. A chair on the corner, the human-size version of the scaled down design metal chairs in the model of the house, opens up to the possibility of a privileged point of view which is however for no one to enjoy – the gallery is in fact closed and the exhibition can be seen only through the wide window of Harbinger. One of the arms of the chair is replaced by a small metal plinth on which a twelve-faced die lays.

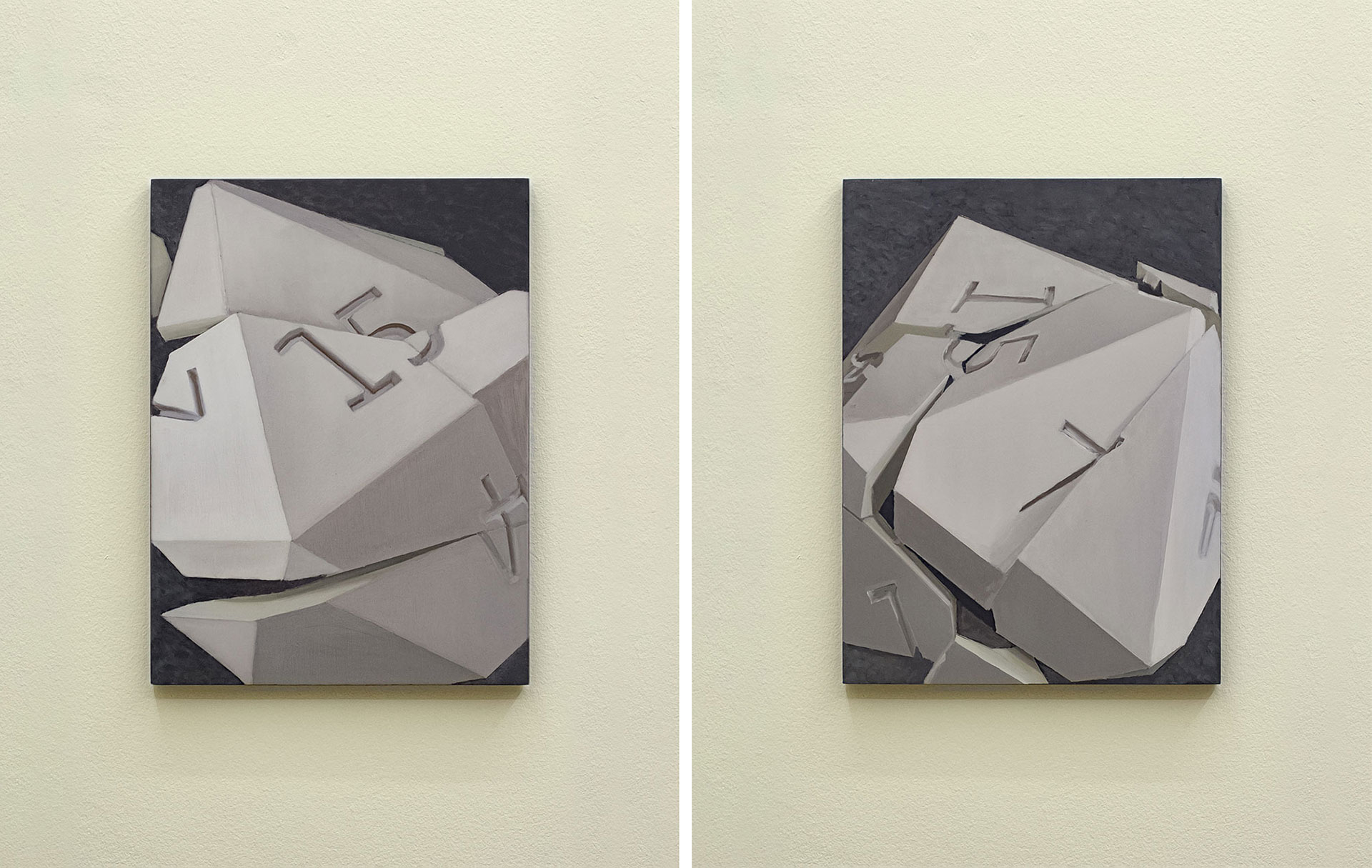

The same die is presented to us in two paintings on the walls of the gallery, but this time is depicted as broken. A painting of a naked person turning their back to us and holding a spear constitutes the only human presence in the exhibition.

Dcethrone (armored luxury), polished steel, sand, dice.

Dcethrone (armored luxury), polished steel, sand, dice.

Detail of dice rolling bowl, polished steel, sand, dice.

Detail of dice rolling bowl, polished steel, sand, dice.

2020, prospect (20 sided die in 20 pieces), oil on woodboard and 2020, retrospect (20 sided die in 20 pieces), oil on woodboard.

2020, prospect (20 sided die in 20 pieces), oil on woodboard and 2020, retrospect (20 sided die in 20 pieces), oil on woodboard.

The exhibition Core Temperature by Fritz Hendrik looks at the future of “our house”, planet Earth, it focuses on and brings together two specific perspectives on the fate of the world: that of those who see the future as a sort of Mad Max post-apocalyptic scenery, where extreme global warming and its consequential catastrophic natural events destroy everything humans have built throughout the centuries, bringing the human species to extinction; and that of those who have faith in the humankind technological progress and believe geoengineering will save us.

Global warming and ecology are issues which are taking up more and more space in global discussions about the future of our species, in particular nowadays, since the year 2020 brought us to face the fragility of our humankind. Coronavirus managed to bring the whole world on its knees. We, first world countries citizens and wealthy enough to be able to isolate in our own homes, have found ourselves lost and broken. We renewed and incremented our long lasting relationship with technology, a companion which gives us access to endless entertainment, allowed us to keep working from home and to engage with loved ones when restrictions prohibited us from meeting in person.

Philosopher Rosi Braidotti in her recent essay We Are In This Together, But We Are Not One and the Same claims that Covid-19 is a man-made disease, it is the result of human interference with the ecological balance. In her opinion it is a paradox that we turned to technology as a result, because that is what caused the problem in the first place. In the same essay she calls for a reconsideration of the binarism between culture and nature, drawing from post/de-colonial and indigenous theories which, in her words, “have a great deal to teach us”. This is for Rosi Braidotti, a time to avoid and fight apocalyptic thinking, it is instead “a time to organize and not agonize”, to reconsider how we live.

Detail of core temperature, mixed media.

Detail of core temperature, mixed media.

Detail of core temperature, mixed media.

Detail of core temperature, mixed media.

Detail of core temperature, mixed media.

Detail of core temperature, mixed media.

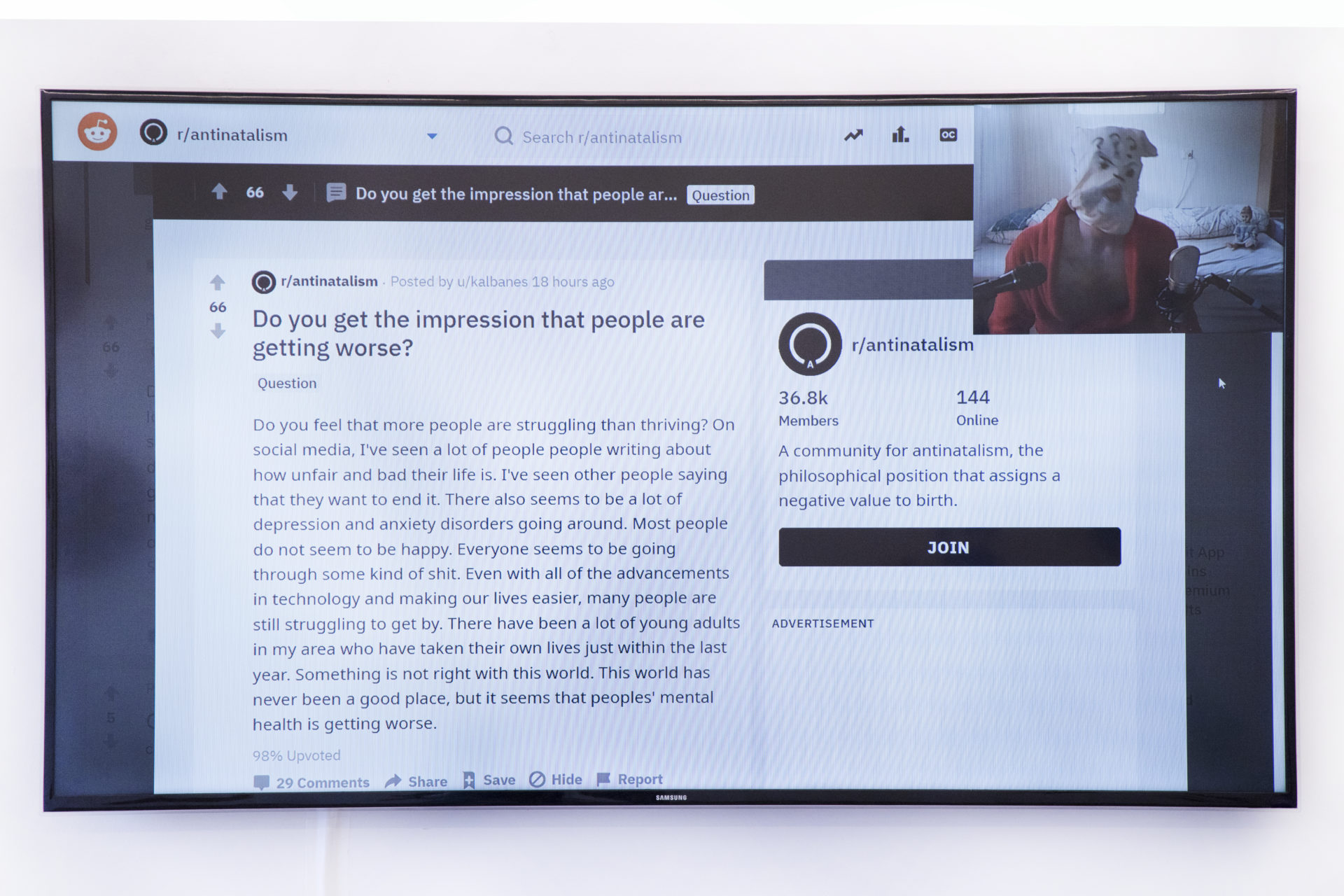

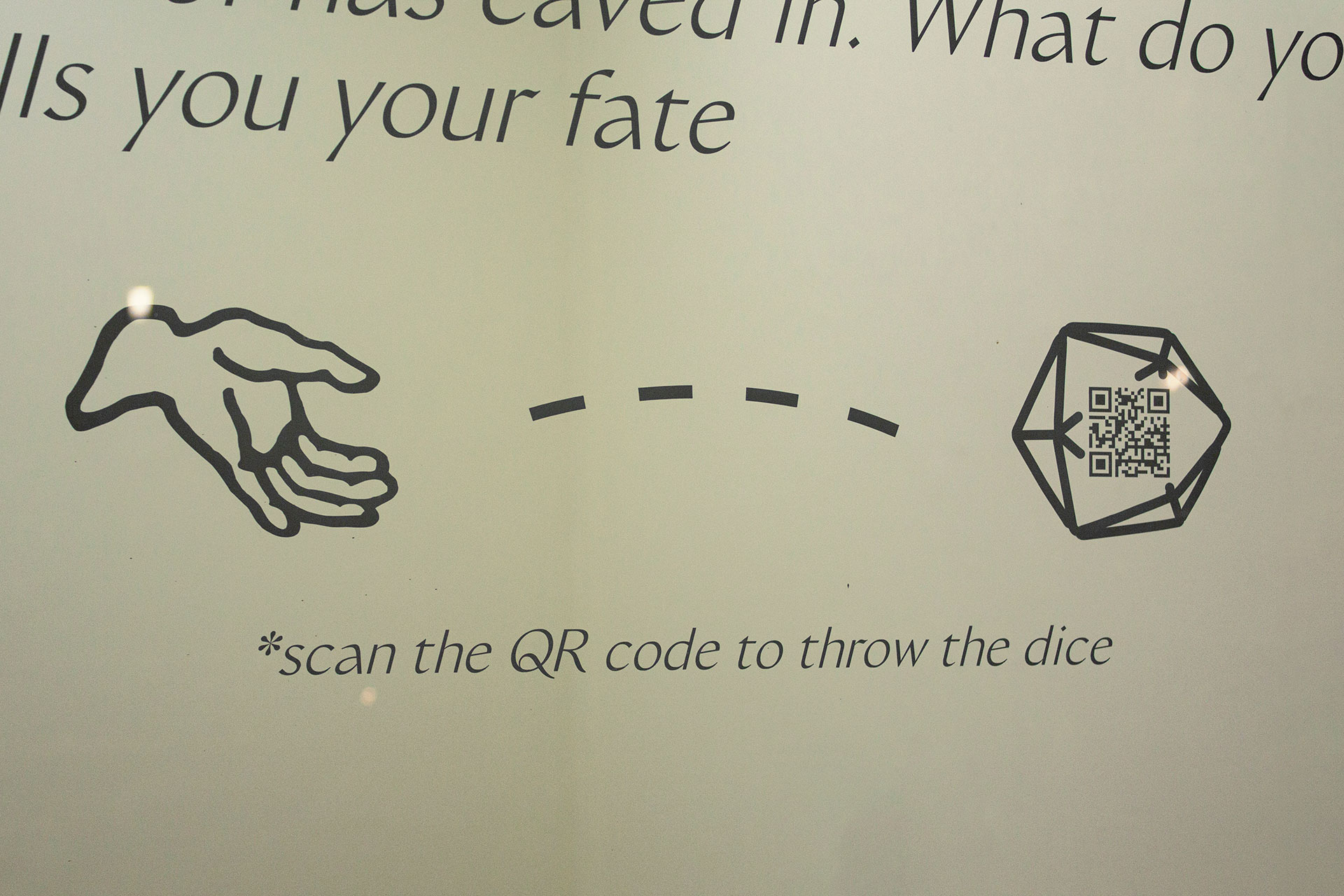

The exhibition is strongly inspired by the roleplaying game Dungeon & Dragons, in which players create their own character and embark upon adventures in a fantasy world. The success or failure of actions taken by players are dictated by the rolling of dice. Fortune plays a big role in the game, as well in the exhibition Core Temperature. Dice appear here and there as symbols of the uncertain result of our actions: the future of our world is beyond our control. A die pops up when one scans the QR code on the gallery window with a smartphone, the polyhedric die rolls into our screens and breaks apart.

Dice are there to feedback on our actions, just like they do in Dungeon & Dragon, to give us a result on which we can adjust our actions for a better future. This does not only concern collective actions taken on a bigger scale by humankind, but also our individual commitment to a more sustainable life-style, small gestures that most of us undertake daily to take care of the environment in the hope to contribute to saving our planet. Despite everything around us collapsing, we still make sure to carefully wash jam jars and beer bottles before putting them in the recycling bin.

The dice in the exhibition represent the questioning of these actions: Are they even useful in the short or long run? Are we contributing in a tiny, tiny, tiny way to change the course of human destiny?

An intact die lays on the chair of the privilege point of view, the empty chair on the corner to which no viewer has access. Capitalism and social and ecological issues are so strictly connected that it is hard to avoid reading that empty chair as where CEOs of big companies and industrialists sit, as they are the ones who could really make a difference, but the capitalist machine is all about one thing: Profit.

Installation view of the exhibition Core Temperature.

Installation view of the exhibition Core Temperature.

Detail, Scorelord, digital print, blý.

Detail, Scorelord, digital print, blý.

Donna Haraway, in her book Staying with the Trouble (2016), talks about making-with, which refers to engaging with the present, staying with other planetary organisms which are facing our same fate. The Covid-19 pandemic has proved that no matter how hard humans like to think of themselves as separate from nature, we are as a matter of fact part of the same ecosystem. That single bottle that we decide to recycle might not solve the waste overproduction problem, as well as cycling might not solve the pollution problem, but all the small actions we take represent steps toward a better society, as well as normalise a way of understanding our position in the world and our role in it which leans toward symbiogenesis – becoming by living together.

The dice are broken, but, after all, it doesn’t really matter.

POV (point of view), oil on woodboard.

POV (point of view), oil on woodboard.

Core Temperature was on view at Harbinger from November the 13th, 2020 to January the 1st, 2021.

Photographs published with the permission of the artist.

Fritz Hendrik’s website: www.fritzhendrik.com