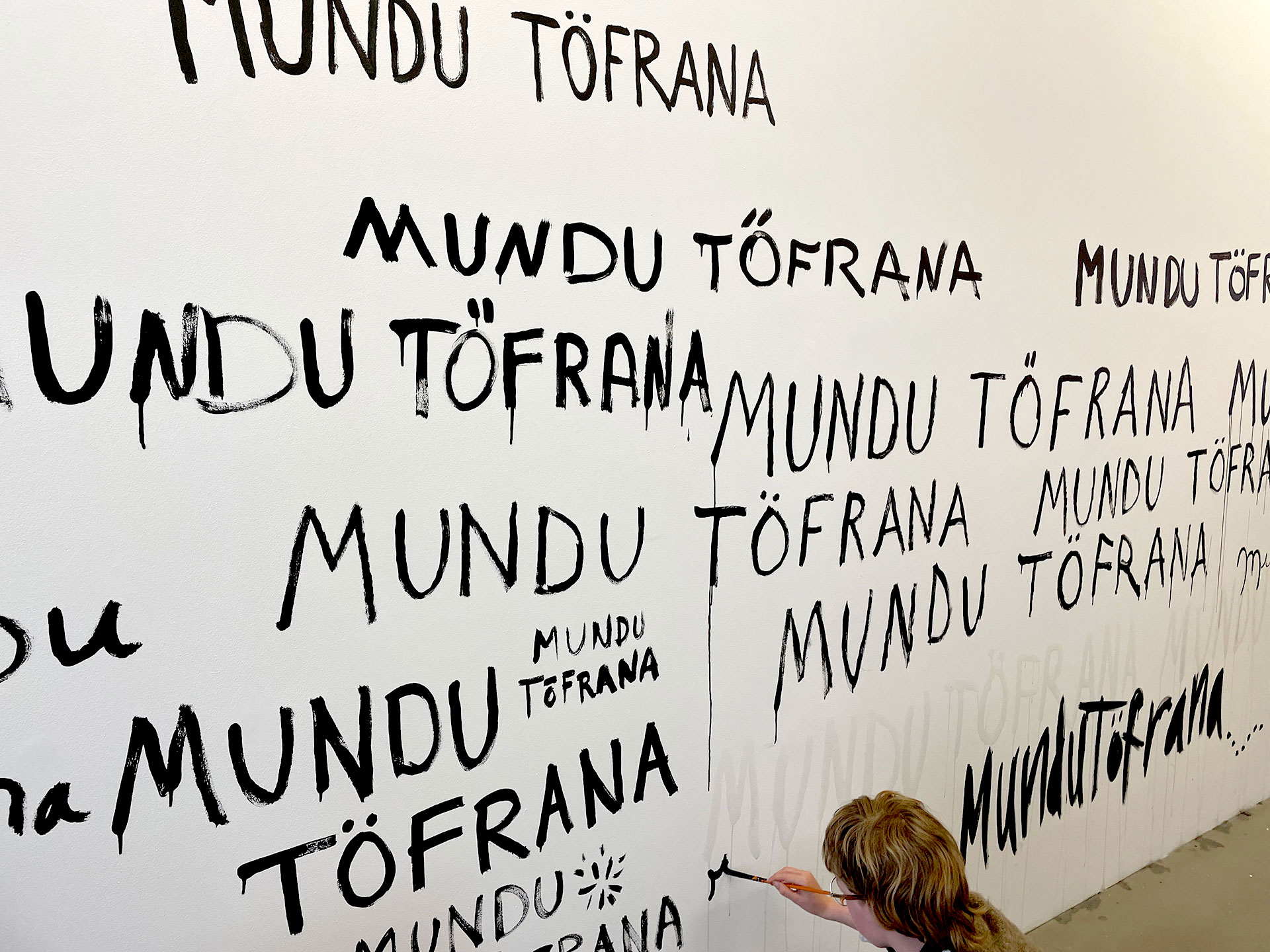

Of Nature and Recollection: The Sonic Convergences in Unheard Of

Of Nature and Recollection: The Sonic Convergences in Unheard Of

“{R]emembrance and the gift of recollection, from which all desire for imperishability springs, need tangible things to remind them, lest they perish themselves.“

– Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition

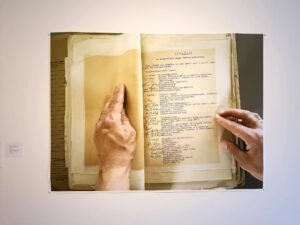

Within the first room, a distorted voice permeates the space. A flat-screen monitor displays a video demarcated into four distinct squares. The top right and bottom two segments of the screen project a rapid, unremitting succession of images: migratory applications submitted by Jews seeking refuge in Iceland during the Holocaust, juxtaposed alongside the Icelandic Ministry of Justice’s processing of said applications. The disembodied voice, emanating from the top left portion, narrates appeals and responses selected from the outpouring of documents, all obtained from the National Archive of Iceland. At the conclusion of nearly every narration, the unvarying, static-laden voice accentuates a single word, resonating sharply throughout the space: “Denied.” Digital Archive Prototype: The Surveillance of Foreigners in Iceland (1935-1941).

Stenciled upon the right wall is a large triangular emblem: Triangle Symbol on Ministry of Justice Draft Form. Inscribed upon the adjacent wall is a three-stanza poem entitled Heimatrecht (Home by Right) by Melitta Urbancic, one of the few Jews granted asylum in Iceland during the Holocaust:

“Why must I make belief,

that home I’m to be

here – after so many deaf

days without sense, meaning – ?”

Clustered throughout the space are elongated wooden boxes housing lyme grass, symbolizing collective atonement, rejuvenation, and renewal. Such constitutes Erik DeLuca’s installation Homeland, a template for revealing and navigating the innumerable complexities of the Holocaust in relation to modern Icelandic history, as well as a rumination upon the political dimension of archiving.

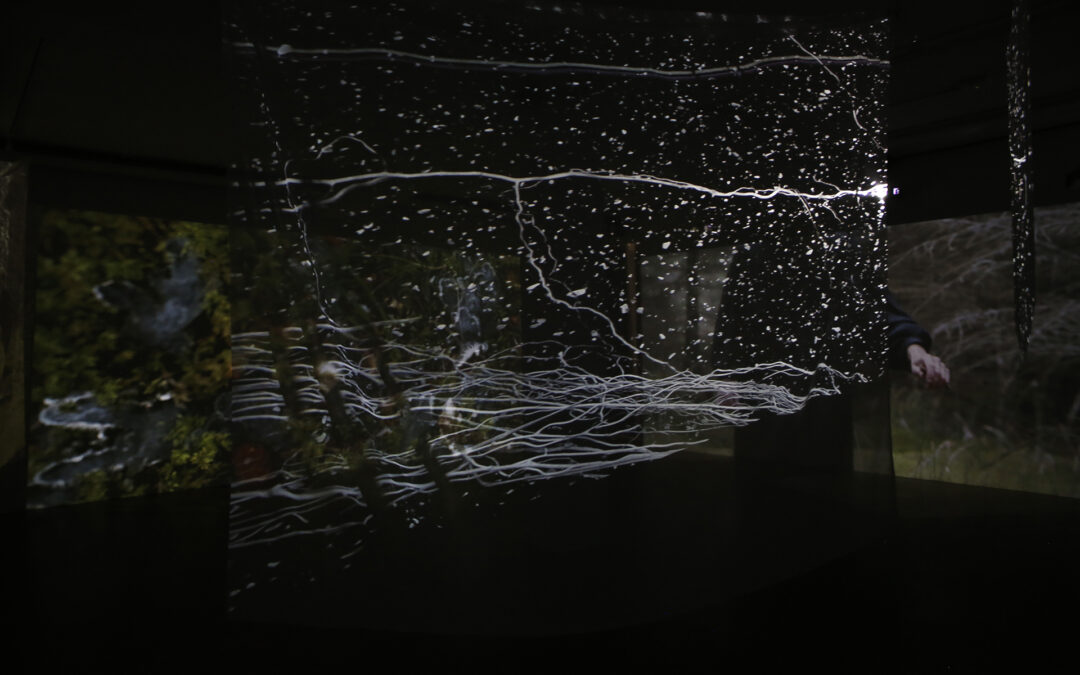

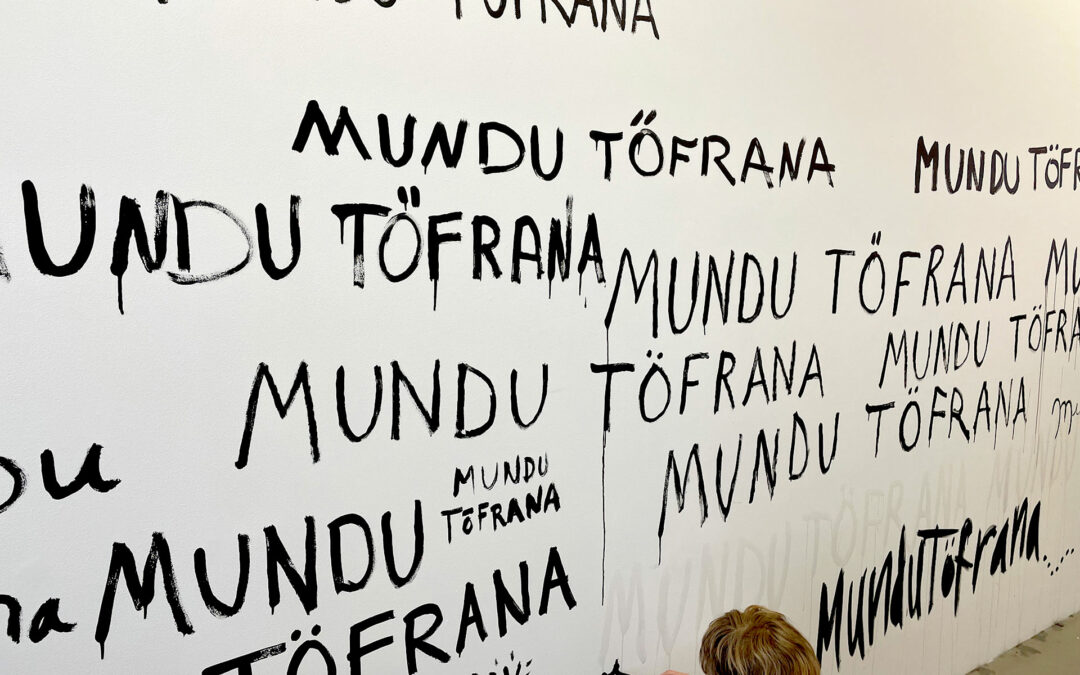

Separated by only a curtain, Þóranna Björnsdóttir´s multi-channel video and sound installation (í)ver(ð)andi (Breathing Water) envelops the second room, submersed in darkness. Reverberating through the installation’s resounding ocean and wind are metal plates, pipes, tuning forks, and bells; the resonant conduits through which Björnsdóttir engages with the natural phenomena of Heiðmörk and Reykjanes Peninsula. To Björnsdóttir, her performative and sonic engagement with the Icelandic environment nurtures sensations of affinity, empathy, and belonging:

I acted towards these places and their phenomena according to the connections I made there and then. I listened and scrutinized the external and internal spectra and reacted to what was happening in that context; with my dwelling, movement, gestures and sounds; an experience based on the direct perception of the senses. The work wants to transfer these experiences into a different kind of weaving; expand it into a new continuum of time and space; explore ways to view, watch, experience, and recreate.

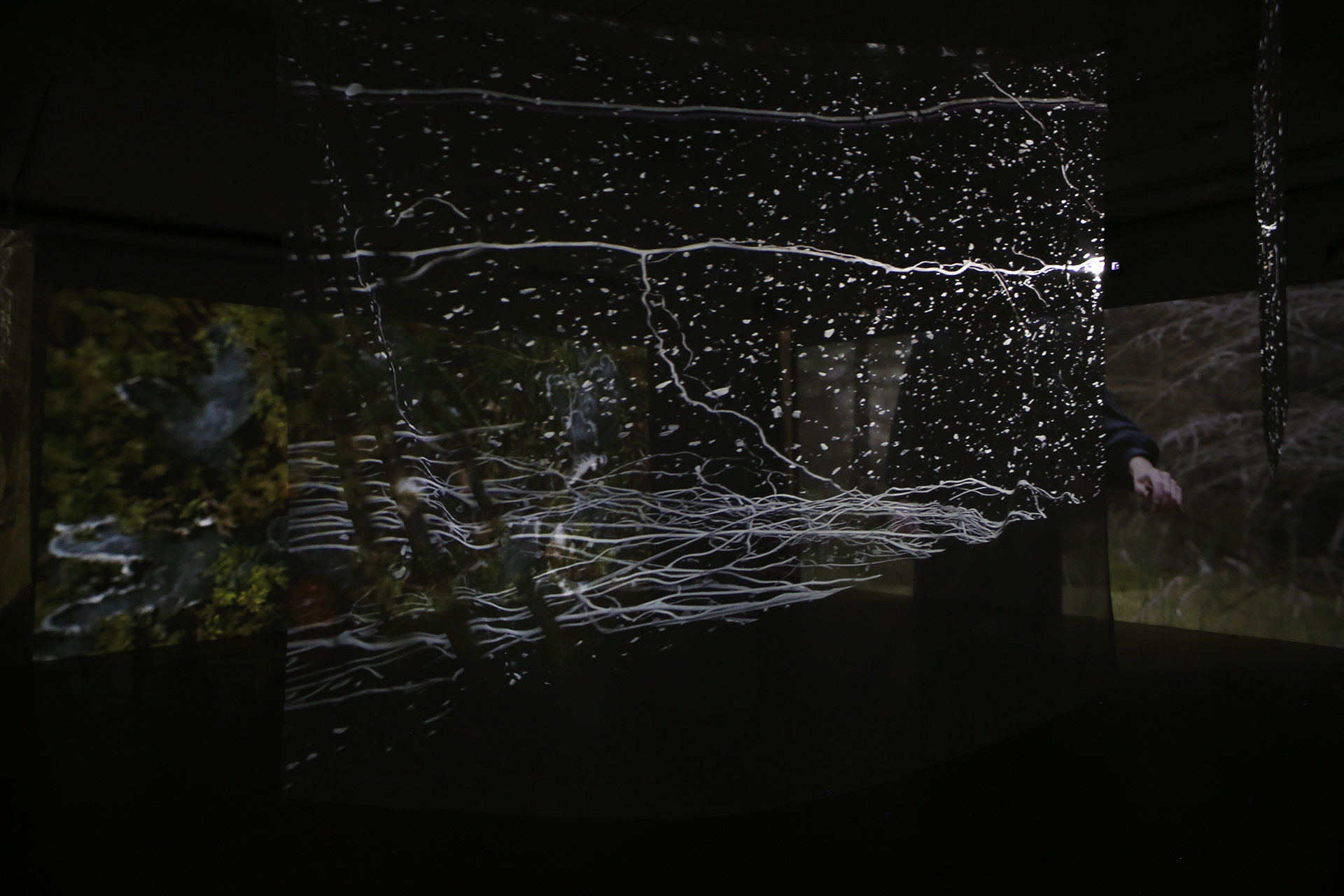

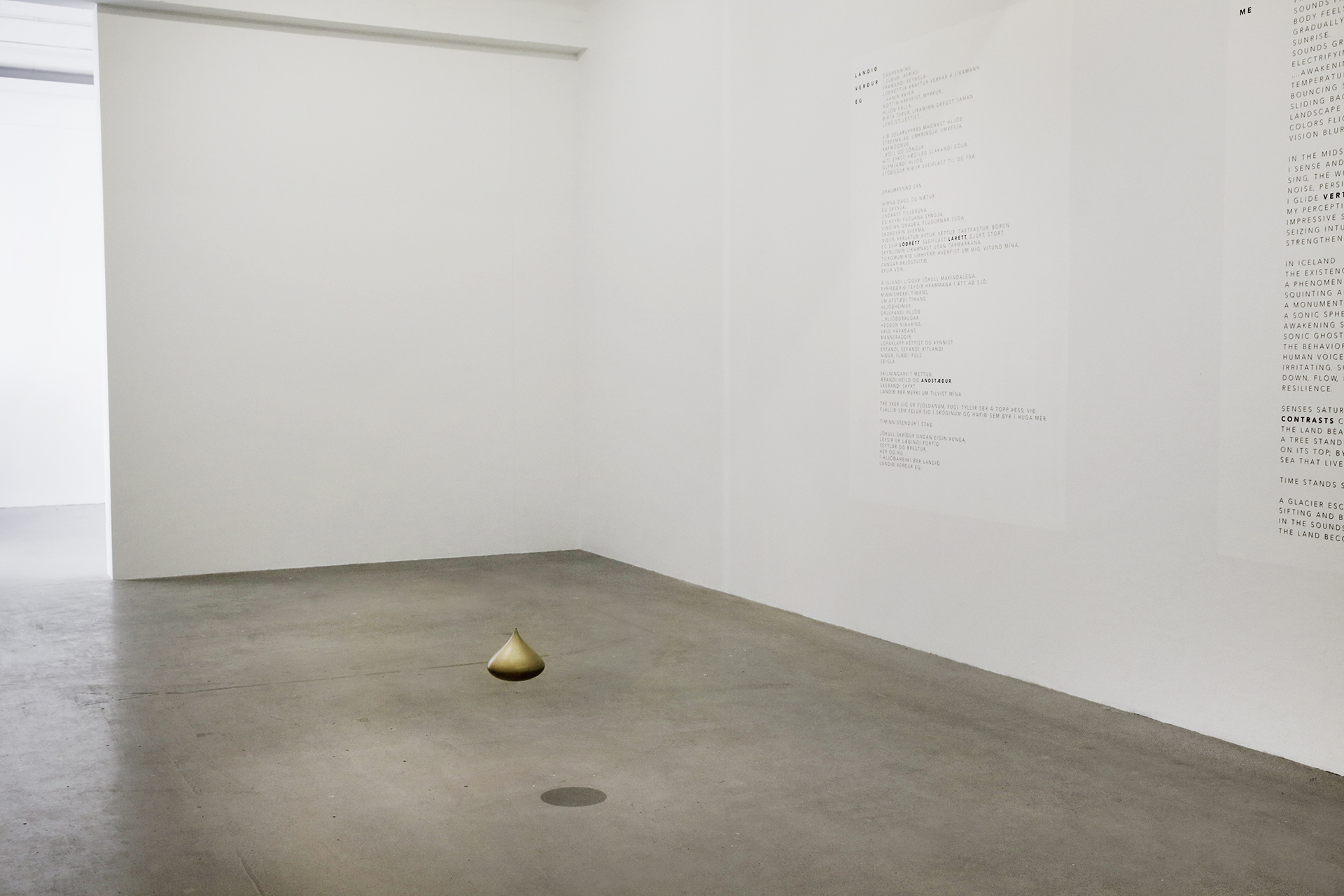

Within the third room, Björnsdóttir’s The Land Becomes Me – a travelogue. The multi-faceted installation, constituted by field research in the Mmabolela Nature Reserve in Limpopo, South Africa and Vatnajökull National Park, probes contrasting environmental conditions through the act of listening. In the room’s center, a mobile sculpture is suspended from the ceiling, which to Björnsdóttir embodies “the effects that the sounds played on me physically, the sensations of internal movements.” Both Breathing Water and The Land Becomes Me are two interrelated facets of Björnsdóttir’s sonic exploration of humanity’s interconnectivity with nature. This notion is articulated further by environmentalist Þorvarður Árnason in the exhibition notes: “Landscape is both ‘something out there’ and ‘something inside me’ – in landscape man and nature meet, the inner and outer environment; the phenomenon of landscape can not be conceived except in the light of these two realities.”

Exhibited in Kling & Bang from August 21st- October 3rd, 2021, curators Ana Victoria Bruno and Becky Forsythe initially conceived Unheard Of as a curatorial experiment, an exploration of the spatial fluidity of sound. Being their first effort in sound-oriented curation, organizing such an exhibition within a highly articulated space like Kling & Bang proffered the possibility for compelling and unpredictable sonic convergences. Intertwined with this exploration of sound´s spatiality, Bruno and Forsythe sought to assemble artists who sonically engage with the world through differing perspectives and methodologies, yet who ultimately employ sound (and silence) as platforms for individualized expression.

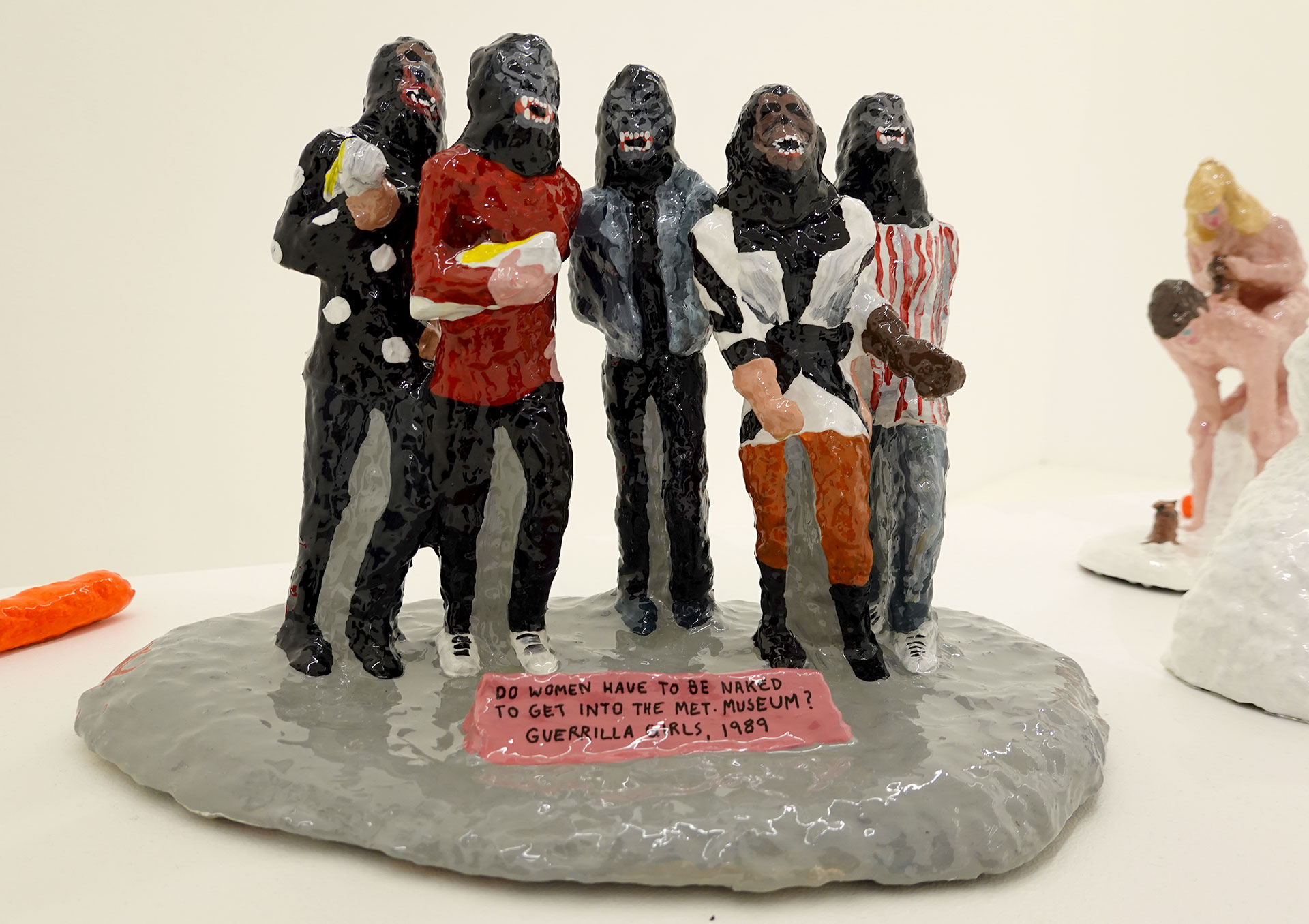

Bruno and Forsythe invited DeLuca and Björnsdóttir to participate, as the curators aspired to both promote broader recognition of the artists, and grant them a platform for conceptualizing and generating new work embodying the distinct particularities of their practices. As both curators noted, DeLuca utilized sound to foster and engage in socio-cultural and historical critique, while Björnsdóttir explored the interrelations between one’s body and emotionality, in tandem with their surrounding environment. The financial and logistical instability prompted by COVID-19 necessitated Bruno and Forsythe to further refine their initial sonic-based conception. As articulated in the finalized exhibition notes, “sound, and expanded silence, perform not as stand-ins for other sensations, but rather a way into opening our ears to things we do not notice, or cannot see.” Through this conceptual framework, the artists and curators of Unheard Of investigated the phenomenological dimensions of sound, a sensory opening through which one not only perceives the apparent world, but unearths that which lies hidden within it:

Sound is a medium that questions and seeks knowledge through a collective action: a concatenation of vibrating bodies that carry information throughout space and time…The artists extend from their sonic-based practices and into process-based conversations by performing, through touch, and in the presence, absence or thought of beings moving through different locations. Unheard Of takes these actions as its starting point and drives them forward through exploratory research, poetry, field recordings, archival analysis, plant cultivation, and immersive sound installation.

Whether due to seemingly dissimilar subject matter, or the various circumstantial strains imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, Unheard Of was characterized by some of the public as disjointed, appearing as two solo exhibitions rather than a single unified showing. Arguably, any thematic or sonic divergences emerging between DeLuca and Björnsdóttir’s installations produced not discontinuity, but rather an unexpected continuity that encapsulated Unheard Of ‘s core tenet of “opening our ears to things we do not notice, or cannot see.”

Due to the structured layout of Kling & Bang, the rooms containing Homeland and Breathing Water could only be divided by a curtain, enabling sound to periodically drift uninhibited between installations. While experiencing Björnsdóttir’s Breathing Water, one could intermittently perceive the austere voice of DeLuca’s installation reverberating outside the curtain, its abrasive timbre slipping into the space. Each occurrence, however faint or periodic, subtly pierced the experiential immersion into Breathing Water, its oceanic roar and metallic resonances momentarily punctured by desperate pleas and apathetic bureaucracy. With each utterance of “Denied,” one encountered the weight of history pressed upon them, making painstakingly evident the voices which have been silenced.

When considering Unheard Of as a unified exhibition, the socio-historical interrogation of Homeland does not invalidate the stark poeticism of Breathing Water. Moreover, Björnsdóttir’s exploration of the individual’s interrelationality with nature is not divorced from the collective milieu in which Homeland is embedded. The chance sonic convergences between Homeland and Breathing Water ultimately disrupt and complexify the trope of nature and universalism in Icelandic art. Through confrontation with a buried facet of Icelandic history, the viewer is compelled to recognize the political and even colonialist dimensions of such tropes. The hegemonic assumption of nature’s universality, a notion oftentimes dissociated from a broader socio-political contextualization, is challenged once positioned alongside the overwhelming evidence of those denied refuge amidst the Icelandic landscape. The sonic fabric of Unheard Of demonstrates the vital significance of intangible reminders of what is not seen, as well as perhaps, what we choose not to see. Through the artists and curators’ collaborative exploration, Unheard Of examines the innumerable dimensions of interiority and exteriority, of nature and recollection.

Adam Buffington

Photo credit: Courtesy of Kling & bang

Photo: Claire Paugam

Photo: Claire Paugam Photo: Claire Paugam

Photo: Claire Paugam Photo: Vigfús Birgisson

Photo: Vigfús Birgisson Photo: Claire Paugam

Photo: Claire Paugam

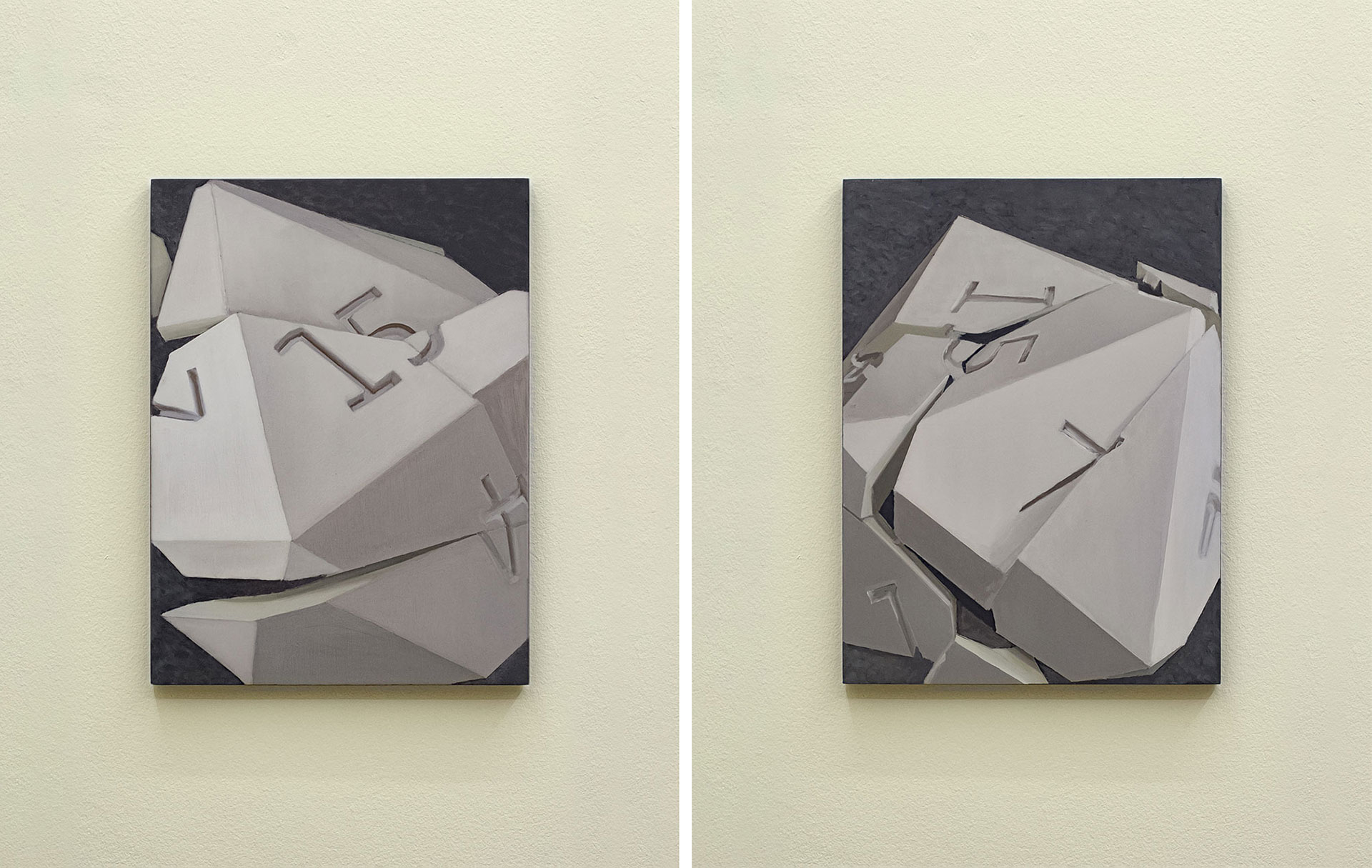

POV (point of view), oil on woodboard.

POV (point of view), oil on woodboard.