Mom’s balls: a show across generations

Mom’s balls: a show across generations

Artists, in order to carry this title, need to be recognized as such from the local and/or international art scene. Besides their creative practice, artists need their works to get out there and to be seen from the art community. They need to be active in the art world by showing their pieces in galleries and museums. It means that artists need to present themselves as artists in order to be recognized as such. But what if someone has artistic skills but does not have the possibility to develop self-promoting abilities and to show his/her works? What if this person lives in the Icelandic countryside in the mid-twentieth century? Probably he/she will never be recognized as an artist unless she is lucky enough to be Elín Jónsdóttir, mother of Ágústa Oddsdóttir and grandmother of Egill Sæbjörnsson.

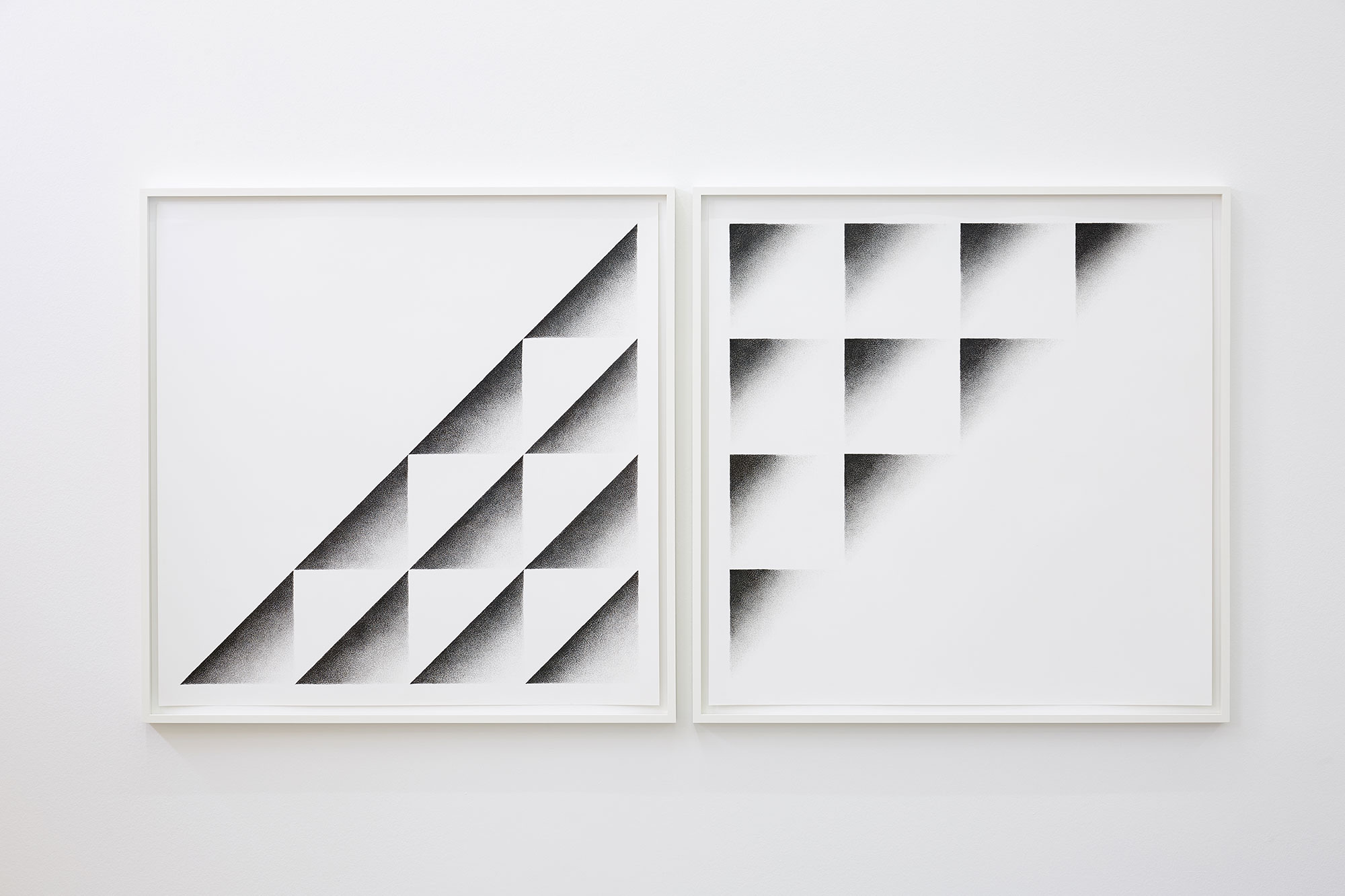

The two artists see in their mother/grandmother an inspiration source for their works. Elín Jónsdóttir had a very creative and modern way of thinking; recycling was essential for her and she was really skilled in manual work. Everything was guaranteed a second life in the hands of Elín Jónsdóttir: old socks and clothes seams were unpicked and the threads reused to make blankets or floor mats. Nothing was thrown away in her house. Even fishing nets and Christmas ribbons were re-worked to become unique shopping bags. But Elín Jónsdóttir’s abilities shine the most in her tapestries: she used to dye the threads by herself, using extracts from plants and vegetables, to create an earthy colors scale. A beautiful tapestry in the bedroom at Neðri-Háls has a particular design composed of both geometrical shapes and figurative decorations, a multilayered work which shows her will to go beyond the reproduction of the visible world, re-elaborating it by mixing some elements from reality, others from a board game and abstract forms.

The exhibition Mom’s Balls is set in three different places: Neðri-Háls, which is the old farm where Ágústa Oddsdóttir grew up with her mother Elín Jónsdóttir, the Old City Library in downtown Reykjavik, and the bar of Hotel Holt.

Getting to Neðri-Háls has an important role in the general experience of the show. The farm is an hour drive from Reykjavik, a lovely trip into Kjos, in Hvalfjörður, and I was lucky enough to go there in one of the few sunny days of this moody Icelandic summer. The mountains coated with bright green grass were flowing through my left car window, the beautiful fiord was gleaming in the sunshine on my right. The little farm has been preserved as it used to appear back in time: the old furniture, the sweet curtains with little flowers, everything looks just like frozen in time. Ágústa Oddsdóttir was there, to warmly welcome the visitors with a cup of delicious coffee and some Icelandic cinnamon rolls. She kindly told me about her mother, describing her as a strong woman and an inspiring figure.

Ágústa Oddsdóttir used to be a sociology teacher when she realized that teaching didn’t suit her anymore, so she decided to go back to school and to join the Icelandic University of Art, willing to move towards art. The influence she got from her mother is visible in her works: she creates big balls made out of stripes cut from old and disused clothes collected through the years. These works refer to a very intimate realm, our clothes are very much connected with ourselves, they function just like a second skin, and they can also be used to communicate our way of being in the world. By cutting stripes from old clothes and wrapping them together to form a unit big object Ágústa Oddsdóttir puts together memories and stories from all the family members.

This conceptual traverse of time and generations is perceptible in her whole practice: some journals on show are visual elaborations of stories her mother had told her. When Elín Jónsdóttir had a nervous breakdown, Ágústa Oddsdóttir used to spend a lot of time with her and they would go for long walks in the nature to have a chat. Elín Jónsdóttir would tell her daughter stories from her past and Ágústa Oddsdóttir would listen carefully, and, once she was alone, she would illustrate her mother’s words and write them down. Elín Jónsdóttir didn’t know about these diaries, otherwise, she would have stopped telling her daughter about her past, because she would have felt used. Ágústa Oddsdóttir has been keeping the journals hidden for many years until recently when she decided to show them.

Those journals show the intimate relationship between the mother and her daughter with an interesting narrative dynamic: Elín Jónsdóttir’s stories have been filtered through the imagination of the Ágústa Oddsdóttir, creating a sort of collaboration between them. The stratification of time alongside with narration are the basis of her work, and they remind us of the importance of recording facts and people memories, but they also remind us that once, before the humans invented the writing form, we were all storytellers, and narration after narration the stories would change and transform little by little, gaining something new from every storyteller.

This narrative aspect is a strong presence also in Ágústa Oddsdóttir’s boxes body of work: she recycles boxes by creating on one side a blank surface with white painting, on which she draws scenes which recall a past childhood. Some boxes are shown side by side and they form a kind of comic strips where each of them represents a scene of a whole story.

Looking at the descent, we can see that Egill Sæbjörnsson has inherited the same interest in narrations, in time-traverses and, in some way, in recycling. His grandmother has been babysitting him for over ten years, spending many hours per day with him and during that time he has absorbed a lot from Elín Jónsdóttir’s values.

Egill Sæbjörnsson has worked around the idea of two trolls, Ugh and Boogar, borrowing the Icelandic traditional trolls and recontextualizing them into the contemporary world. He has developed the concept of troll: Ugh and Boogar are curious about everything, they are eager to learn and to create, they imitate Egill Sæbjörnsson because they want to understand how the human beings have developed. Egill Sæbjörnsson gave the trolls a new life through his work. He created a new narrative for them to exist in the contemporary world, a process which is reminiscent of his grandmother’s approach to recycling.

Ugh and Boogar were actually born as a private joke – two alter egos he created just to have fun – but then he developed their stories through his artworks making them almost real. At the Old City Library, there is also a video of Ágústa Oddsdóttir getting into her alter ego character named Guðmundur Jónasson, a bus driver, another art piece which was born just as a joke but that has been transformed in an actual artwork.

Egill Sæbjörnsson’s interest in narration and time-traverse can be seen also in his piece Afi minn for a honum Rauð, on show at the Old City Library in downtown Reykjavik. This work consist of a photographic series based on an old Icelandic children song from 1998, Egill Sæbjörnsson has been once again borrowing something from the past and re-elaborating it to create a new narration. The process is reminiscent of his mother’s journals as in both of the pieces, the original story is filtered by the artist’s imagination which produces a personal interpretation, a meeting point of different times and of understandings of the story itself.

Mom’s balls recontextualizes work by Elín Jónsdóttir, whose potential has been seen by the British-American art critic Karen Wright, curator of the show. Elín Jónsdóttir’s creations have finally been placed in that context to which she had never had the opportunity to access. But the presence of her works in the show enlightens that of Ágústa Oddsdóttir and Egill Sæbjörnsson: the dialog through the works reinforces the artwork themselves, empowering them with a new strength and giving us the key for a new understanding of their practices.

Ana Victoria Bruno

Photo credit: Helga Óskarsdóttir