A Triangle Dreaming of a Triangle – an Interview with Ignacio Uriarte

In Ignacio Uriarte’s exhibition, Divisions and Reflections, now on view at i8 gallery until August 4th, the black and white drawings create a suite of connective material, like the tissues of the same organic world of shapes. Uriarte is known for his background in business administration which he has carried into his artistic career by using the same tools of the trade – those belonging to the office. However, in this office space, the traditional ways of looking at the use of objects are given a new formula that explodes the mundane aspect of the work to touch on the body-machine relationship where tools are extensions of bodily functions still restricted yet extended. In an interview, the artist spoke about the way narrative is written into signs and symbols in a way in which the signs and symbols can be nostalgic and even dream of themselves.

Erin: Your background in business administration has really been the focus of a lot of the writing I have read about your work. I watched one of your earlier works in which an actor performed the sounds of a typewriter. It really gave these tools an embodied aspect, like a Cronenberg effect. It seems like a similar effect goes into your drawings by making a caricature of the body as a tool.

Ignacio: The typewriter is a writing instrument but it is almost played like a keyboard with the sounds of a percussion instrument. It used to be the soundtrack of the office and was used in movies when you wanted to announce that someone is entering the pressroom or the office. The typewriter just belongs there, but it’s a bit of a pity because the typewriter really inherits that world wherever it goes. I wanted to do homage to the sound qualities of the typewriter without showing a typewriter.

I recorded in a technology museum where they have thousands of typewriters and every couple of years they have a different model, electrical ones or ones with digital memories with each typewriter having a different sound. The actor is basically listening to the original sounds and recreating them with his mouth. The History of the Typewriter Recited by Michael Winslow (2009) is the name of the piece. The work had so many reactions with people from the art world reacting in a certain way, typewriter fetishists reacting in a certain way, and beatboxers reacting in another way. It was so funny to have all these reactions.

Erin: That’s the magic of how a simple thing put into a new context can have a different meaning for so many people. Off the top of my head, Naked Lunch is my first typewriter association.

Ignacio: Yes, a typewriter turned into a living being. I think a lot about Cronenberg [David Cronenberg, the director of the film Naked Lunch based on the novel by William S. Burroughs] in my work in general and the interactions between man and machine. Often, with him, it’s the physical connection of man to a machine.

Erin: There is a really strong connection when you think of office work and this constraint put on the body, as in the typewriter; the act is so physical.

Ignacio: I find with the typewriter that there is another aspect of the way we become digital. For the people who grew up with pre-digital technology, the typewriter has given us quite a lot of help. You have the idea of the function of a paper where you can copy things and take them out again. These physical things were taken from the computer screen.

Throughout the filming, I came up with these very constructed drawings that often take a letter or a sign like in concrete poetry where they take a word or a concept that is a visual image but is also a visual result. So I started moving in that direction of taking a sign and seeing what sign is makes in space. Now, I do a lot of drawings in that manner. Sometimes it becomes way more organic than you would expect from an instrument. I make curvy lines by slowly rotating the paper and it gives you images you wouldn’t expect from a typewriter.

Erin: It really brings together the notions of art and poetry and art and writing. I was thinking a lot of the Oulipo (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, or workshop of potential literature) movement in the 1960s in France, a group of writers who put these constraints in their writing to make it sort of mechanical, similar to how you work within the constraint of using office supplies. These writers would create a boundary for themselves from which to write so that the whole meaning of what was within these boundaries could be expanded: writing poems using only one vowel, for example.

Ignacio: For me, the use of office material was a way to stay rooted in reality. I tend to go for these images that are rather universal, minimal, or abstract. When you restrict yourself to certain tools, as well as methods, it is not the typical gestural painting of beauty out of intuition, but more about someone adjusting and obeying an everyday life situation.

Erin: It seems that this exhibition is more of an organic geometric world with these kinds of shapes, much more so than your previous works.

Ignacio: It is very new for me to move into the shape to begin with. This is the second show in which I’m influenced by geometry. You can see the influence of these Swiss designers, like Max Bill. First of all, it is a very reduced language; Bauhaus didn’t invent it. The Catholic Church began it. We’ve been doing this for a long time – when you want to find a universal symbol you tend to reduce it. I remember being taught in a Montessori Kindergarten in which kids are taught to read with symbols, so the verb is a red circle, as it is a movement that’s jumping around, and the article is a triangle, as it is set in place. In a way, I’m using what the Bauhaus educational system used. It’s appealing because I’m still bringing the empty container in which everyone can bring his or her own whatever-is-in-their-mind. It is a very playful way to explain the world and there is some optimism. I think the show even looks a little bit nostalgic of the 1960s.

This one, in particular, Ten Documents (2018), with the op-art effect may remind you of when people were using drugs in the 1960s, like the doors of perception. The work is actually about the size of the DIN system. In Europe, the sizes are designed by German engineers in which DA 0 is exactly one square meter and if you divide it by half, which is half the space, then it is DA 1, DA 2, DA 3, and so on and if you turn it around it is exactly the same orientation. There is a lot of method involved. It was invented for the First World War and for a really big war you had a lot of office administration. So for this square, if you calculate it, you can easily think that if you need this many pieces of paper, you know you will need this many pieces. Many things were invented for war purposes that had a very positive use in society and they usually put a lot of research into it. The thing is, you don’t think of war as being in the office. So, although the work has this op-art effect depending on the perspective, I call it Ten Documents to bring it back to reality.

And with this one, Eight Circles Forming a Square (2018), it is rectangular and I tried to make a square with eight circles by playing with halves. The end result is these overlays, typical things you use to explore shapes.

The whole show was made with the same pen. There is something about transparency and overlap in Four Rotating Squares (2018), the way the more you overlap the darker you get. There is a kind of summing up of surfaces in the way that this is a circle trying to become a square and this is four squares becoming a circle. It is a very simple gesture in which you have these shapes and then you have this effect. It is so simple and universal, this shape; it is like a sun freeing the shape of the sun. There is always a bit of transformation happening – a triangle dreaming of a triangle.

Erin: Creating triangles with triangles sounds like a format for concrete poetry. It almost seems like a formula in which you can only use the thing you are creating to create the thing you are creating, almost like a mise en abyme event.

Ignacio: This triangle also relates to the square. It’s very constructed. That’s why, to me, the exhibition space is a choreographed space. They are part of the same fabric – a suite of works that talk to each other.

Erin: Has anyone commented on the overt hairiness of these strokes?

Ignacio: In other pieces, people say they look like sweaters. One idea with the strokes is their relation to chance more than to scribbling. It has this very chaotic, organic, physical, almost biological feel to them. The making of these strokes is so anthropomorphic, as well. The repetition and the natural movement reflect the size and radius of your wrist. This work is called Chiasmus (2018), like the narrative structure used in literature. It could be representative of this narrative structure in which the second part is mirrored against the first part but with a role reversal.

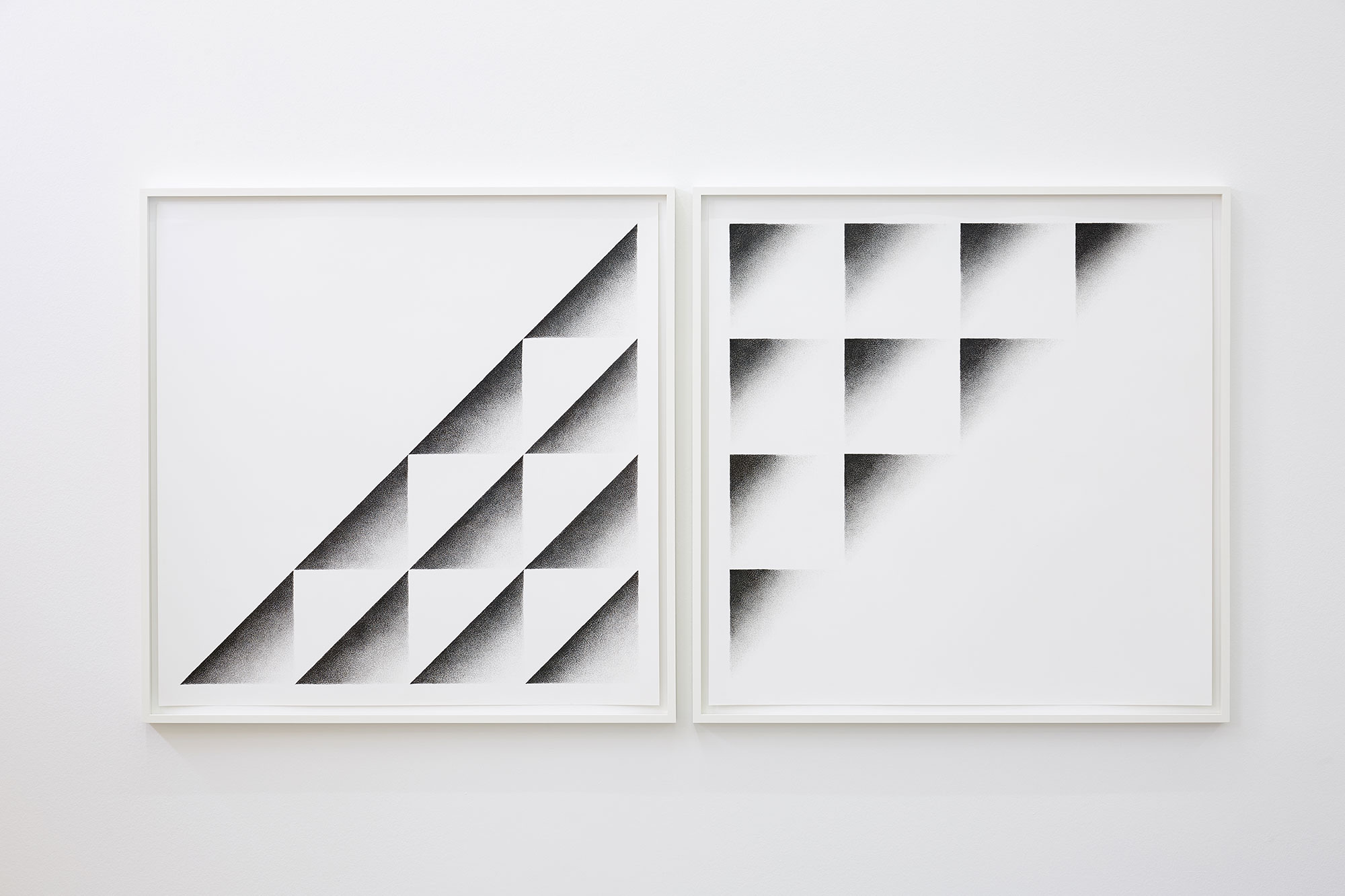

In these works (Two Quarters, Four Eights, and Eight Sixteenths (2018)) you can see this Cronenbergian worm that is being divided. The space each shape needs is compacted. Because I left the same procedure for each one, the paper is what gives it shape, but it is almost like the space has to give it shape. I am not trying to distract from it. You’re getting into the consequences of a system that works very well on the viewer and the reader and then suddenly your personal story becomes extremely universal of that consequence. The question in any art form is: What do you want? Do you want an artwork or do you want to live in an artwork? Do you want to distract or, through it, understand reality better or do you want to come to a realisation of something?

Erin: With these questions in mind we thank Ignacio.

Erin Honeycut

Photo credit: Featured image by Marcel Schwickerath. Images of works: Vigfús Birgisson.