Eygló Harðardóttir and Leifur Ýmir Eyjólfsson Take Home Awards at the Icelandic Art Prize

Eygló Harðardóttir and Leifur Ýmir Eyjólfsson Take Home Awards at the Icelandic Art Prize

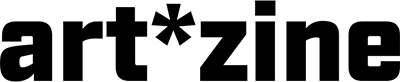

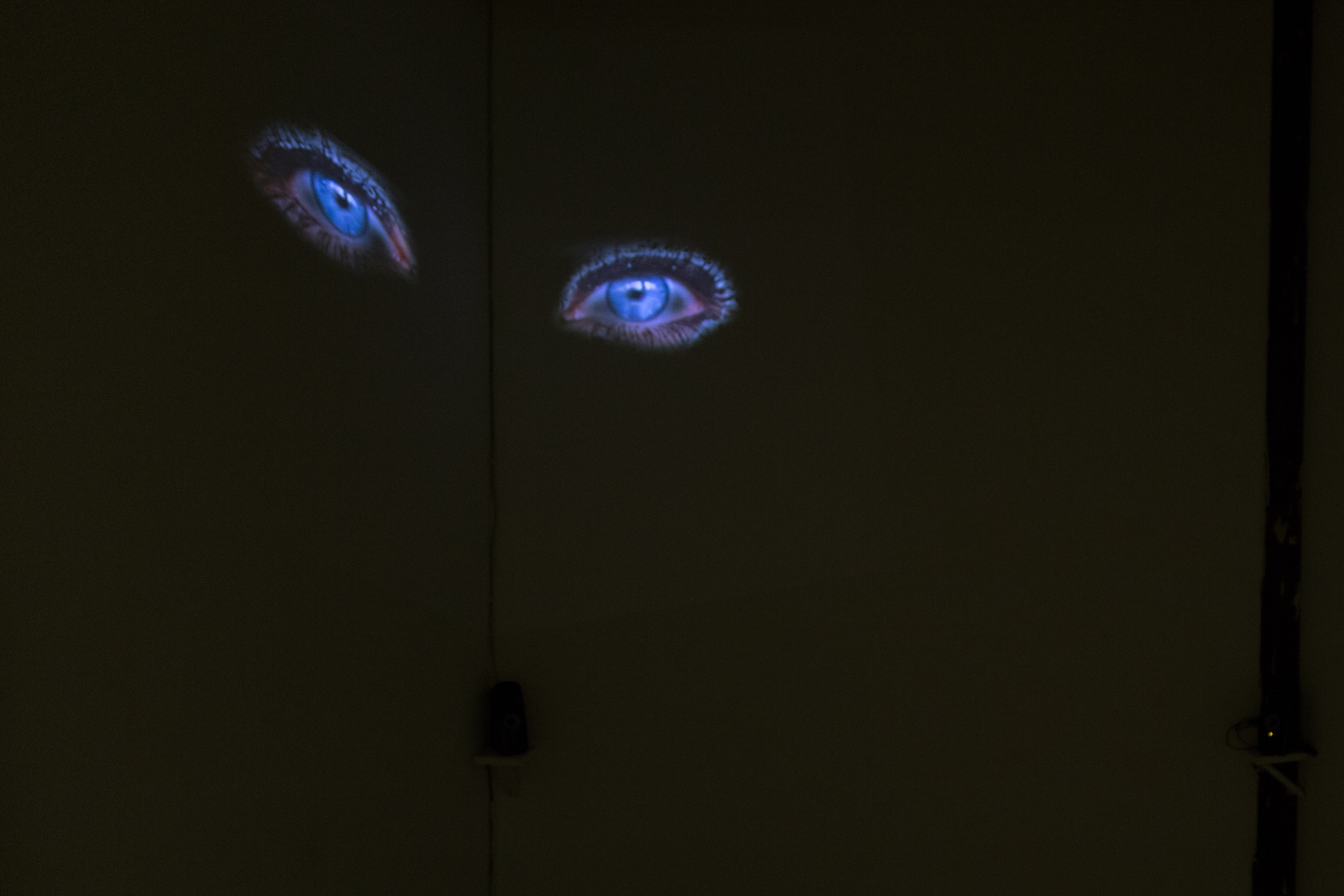

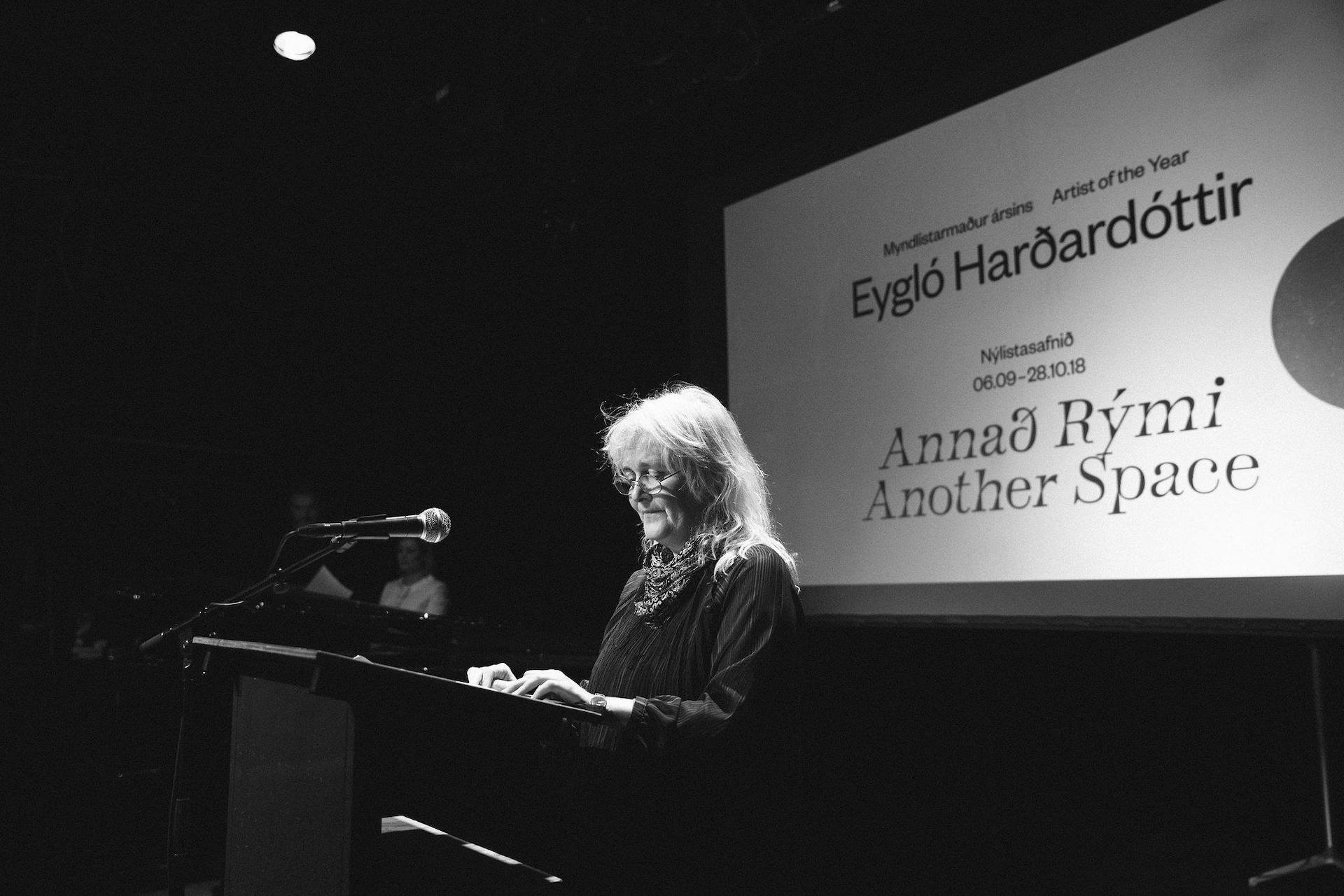

“Time is money, it’s cliché, but it’s quite simple and true.” I’m sitting with Leifur Ýmir Eyjólfsson in his studio in downtown Reykjavík over coffee, as he builds shelves to house and protect 250 ceramic plate artworks coming from the Reykjavík Art Museum. He recently closed an exhibition there, entitled Manuscript, for which he won the Encouragement Award from the Iceland Art Center this past week. Winning alongside Leifur was Eygló Harðardóttir, who took home the prize of Artist of the Year. Her winning exhibition, Another Space, showed at Nýlistasafnið this past year. “It is like Hekla Dögg Jónsdóttir has quite beautifully told me”, Leifur continues, speaking about a fellow nominee for Artist of the Year, “art is quite delicate, like a precious flower, you have to protect it and care for it, and programs like the Icelandic Art Prize do just that necessary work.”

The Icelandic Art Prize was established by the Icelandic Visual Arts Council in February 2018, awarding exhibitions that took place in the year 2017. Margrét Kristín Sigurðardóttir, the Chairman of the Icelandic Visual Arts Council since 2016, tells me that these awards are “intended to contribute to promoting Icelandic contemporary art, both in Iceland and abroad, as well to draw attention to what is well done in the field. The prize gives the opportunity to direct the spotlight at what is considered outstanding in Icelandic visual art each year.” Two recognitions are awarded, Artist of the Year, awarding 1 million ISK to an Icelandic artist who has shown outstanding work in Iceland, and the Encouragement Award, awarding 500.000 ISK to a young artist who has shown outstanding work publicly in Iceland.

“This recognition is quite precious, really, feeling that someone really is paying attention to my work, it is a really amazing feeling, but it is hard to describe,” Eygló tells me when I ask her what this award means to her. “When you work in art you sway between being insecure and paranoid, asking yourself ‘is what I’m doing working?’, all the while believing in the work and pepping yourself forward. Often there is a lot of silence around art in Iceland, so programs like this perhaps open up for a different way of thinking about art, artists, and exhibitions, and of critically comparing and talking about each other’s work. I think this program could have the affect that people visit exhibitions a bit differently, because when work is brought into comparison to another’s a certain suspense begins to build.”

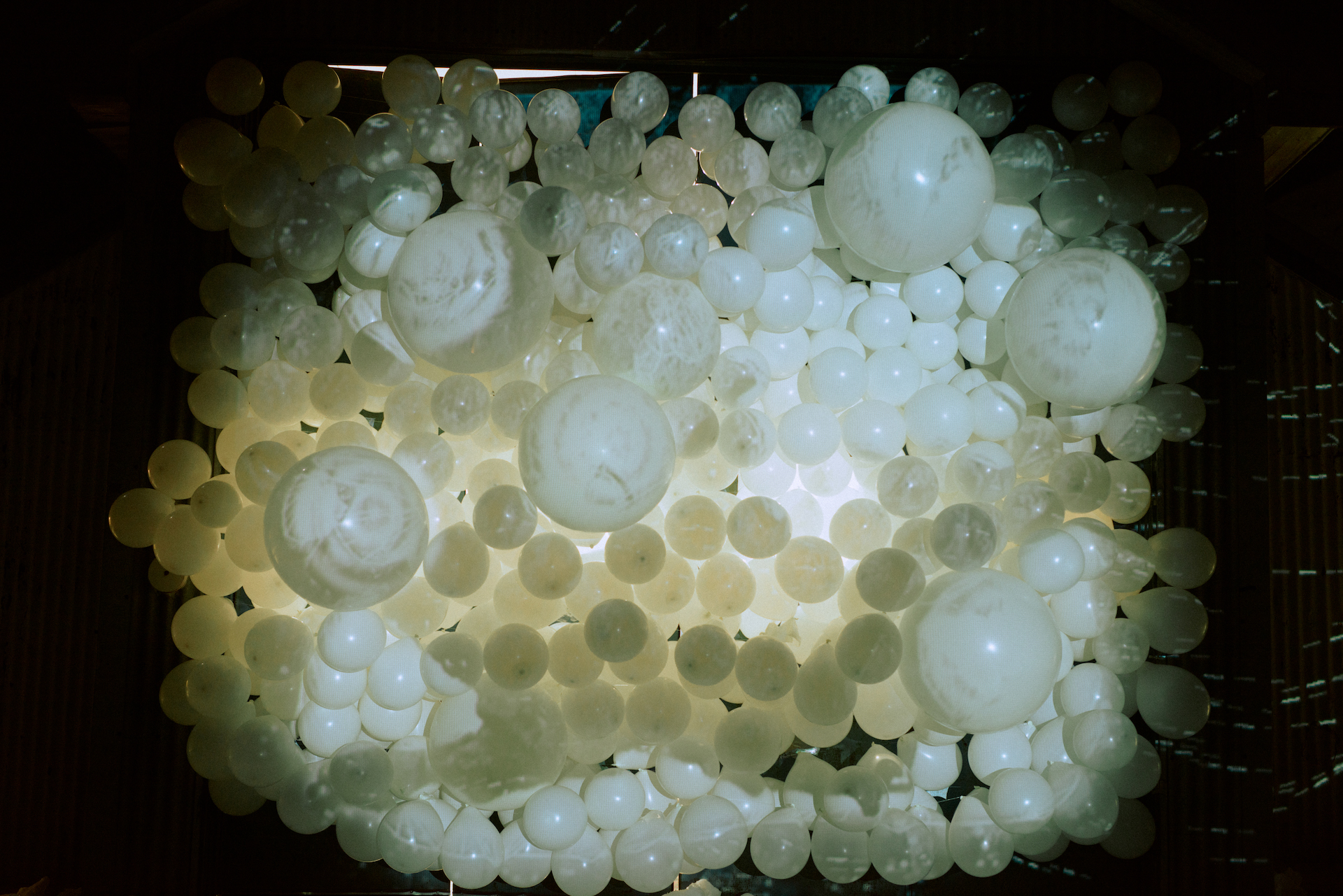

Leifur similarly recognizes the important effect awards like these have in awakening a necessary conversation around art in our community. “You are very vulnerable, and ego is of course some element to this. It is in our nature to search for some sort of feedback. Like the name of the prize says, it motivates me forward, and it awakens a conversation and an interest, which is a beautiful thing.” He explains to me that his exhibition, Manuscript, was really a process of baring himself bare to the world.

“I am also awake to the fact that it’s all contextual,” Eygló reveals to me. “This year my exhibition was in the right climate for this moment, but perhaps it may not have been last year or next year. So you can’t really say that some one thing is best, artist, or art, or otherwise. This really matters to me. Criticism here in Iceland has so often been about good or bad. Even if there is only one prize, it’s not always about better or worse, but about opening up communication and critically comparing and talking to one another about art.”

Margrét explains to me that the public submitted proposals for nomination of the two prizes, and that she was quite pleased by the large response of submittals. The jury then decides together who is nominated in each respective category. “The members of the jury are people with extensive knowledge in the field of art, representatives from the Association of Icelandic Visual Artists (SÍM), the Icelandic Academy of Arts, the Visual Art Council, the Icelandic Art Theory Association and from art museum directors in Iceland. During the decision process, each member of the jury presents their views on each artist and his work. If the jury is not unanimous we vote, the artist who receives the majority of votes is then nominated.” Margrét has been the head of the jury of the Icelandic Art Prize since it was established, and was joined this year by Aðalsteinn Ingólfsson from the Art Theory Association, Sigurður Guðjónsson from the Icelandic Academy of Arts, Jóhann Ludwig Torfason from SÍM and Hanna Styrmisdóttir from art museum directors in Iceland.

When discussing the future of this program, Margrét is optimistic about its continuing growth and evolvement, hoping to expand the categories as the art scene in Iceland continues to expand and flourish. “It is important that each year we pay attention to the visual art scene in Iceland and celebrate what is outstanding. The awards should attract deserved attention to Icelandic visual art.” Like Leifur emphasizes, the grant and awards process is a critical and necessary element to working in the arts, and he is hopeful that programs like these will only continue to grow over the years. “This program is such a good addition the professional art scene here in Iceland. The grant process is so necessary and essential, and it is so important that these opportunities for artists are growing to the point where it is almost hard to keep track. It’s such a positive.”

Like Margrét emphasizes to me, these types of programs give necessary recognition and motivation to outstanding artists in Iceland. “As the aim of the Icelandic Art Prize is to honor and promote outstanding Icelandic contemporary art and encourage new artistic creations I hope it will give the nominated and awarded artists great opportunities. They deserve to get attention and hopefully it will encourage them to keep on their good work. I think it is important that the prize has established itself and that it will be desirable to receive the awards.” This prize then functions as an important and valuable tool that she hopes will be a growing part of the art scene in Iceland in the future.

“There is always this question, what comes next”, Leifur laughs as I probe him about what the future holds for his artistic practice. “I’m a little shy about it. It’s a clap on the back but at the same time a kick in the butt. It equates to fire, kindling to keep my ideas flowing and developing. It’s a hard question, it hasn’t quite registered in me yet, but it’s amazing, and I want to say how thankful I am.” Like Eygló reiterates, the financial aspect of this award does not go unnoticed or under appreciated. As an artist, “a million ISK can stretch out as some months of salary, and I’m very pleased with that, to be able to go work somewhere and only on my art.” Leifur similarly emphasizes that this award gives him a moment to breath and develop his next projects. “For me it really comes down to time, the classic time is money, money is time dilemma. Now I can focus on the time aspect of this equation and take a moment to transition, to reorganize both physically and mentally, and to place myself mentally in the next project.”

Next on the horizon for these two remarkable artists? Eygló tells me she has three exhibitions planned in Northern Iceland over the next year, all at artist-run spaces, an important element to her. “I respect these types of spaces so much, and I find them very exciting. At Nýlistasafnið, for example, there is the same wonderful vibe that has been there from the beginning, a very positive energy, of people working together and supporting each other. Everyone has a voice and there is no sense of hierarchy, no sense of stress, but rather a beautiful trust between everyone on staff. In August 2019 I will show in a group exhibition in Hjalteyri, working with curators and project managers Erin Honeycutt, Bryndís Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir, and Geirþrúður Finnbogadóttir Hjörvar. The show is titled Mild Humidity – The (Digital) Age of Aquarius. It is quite a special project, evolving very much from the conversations between people around it and the ideas that come forth. For a studio based person like me it is quite exciting.” Eygló will also show at Alþýðuhúsið in Siglufjörður in 2019, as well as at Safnasafnið in Akureyri, alongside Steingrímur Eyfjörð and Anna Júlía Friðbjörnsdóttir, who was nominated for the Encouragement Award last year.

“I have so many ideas, old and new that I’m working through currently, projects that I’ve been working through for some time that need time to evolve as I work through a transitional stage” Leifur tells me. “I think a lot about the working day, and how different people approach their time in a day. Me and friend and coworker Siggi have been working on an interview project around this concept, how we treat the work day, and the time therein. My work from Manuscript is also going to be showed in different spaces now, where smaller selections of the plates will be shown together, so the work will change in that way. This work really depends on the space it’s displayed in, because people connected with and responded to this work in such an interestingly personal way.”

Daria Sól Andrews

Photo Credits: Sunday & White Photography