Iridescence, domesticity, and sweaty cheese: a show and tell with Anna Hrund Másdóttir

Iridescence, domesticity, and sweaty cheese: a show and tell with Anna Hrund Másdóttir

I remember the first time I had a Pop-Tart. It was Frosted Strawberry flavoured, with a thick, shiny, baby pink glaze and rainbow sprinkles smeared across the top. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect but I had a feeling it would be sweet, so it drew me in immediately. It was clearly processed, and too artificially seductive and modular to be “real” (yet it was). I remember my six (or so) year old self staring at it for a while, confused and curious as to how to approach it. (Do I break it in half or bite right in?) I bit into a corner and discovered that it was filled with strawberry “jelly”. The pastry crumbled all over my shirt, and I felt an unexpected wave of rebellious satisfaction. It tasted exactly how I imagined: sugary, with lots of layers and textures, and an overbearing essence of artificial strawberry running through it. It was satisfyingly synthetic, and I was hooked.

I revisit a similar joy whenever I encounter Los Angeles-based artist Anna Hrund Másdóttir’s work, as it often prompts me to question and revisit the reality, possibility and integrity of the seemingly mundane. There also exists a similar rebellious satisfaction when visually ingesting the vividly (un)real yet organic nature of her practice. Both highly saturated, odd, clever and appealing from the outside, and only more satiating as you dive in.

Three time zones and over 4,000 kilometres apart, I find myself in a beautifully strange conversation with Anna Hrund. Meeting across the internet, we covered everything from her favourite authors, to the wonder of Jacaranda trees, to her curiosity with cocktail cherries. Anna has this way of weaving connections between seemingly unrelated objects and things in a way that only seems a given after you see or hear it from her yourself. With a background in mathematics, it’s clear that her approach to life and the objects within it is methodical, but I prefer to think that her unique mindset fundamentally stems from her genuine love of curious things. Working within self-generated systems of categorization and logic, she fuelled my curiosity as she generously talked me through her current cerebral landscape.

As our conversation unfolded, Anna spoke to me about some of the objects and things that are currently occupying her headspace. Most resonant, perhaps, was her enthralment with the writing of M.F.K. Fisher, the iconic American writer from the 1900’s who was un-paralleled in her ambitious writing on food culture and gastronomy from a woman’s perspective. Fisher wrote candidly, intimately and honestly about her experiences and interactions with food, as well as the practice of eating, preparing and enjoying it. Anna Hrund spoke so fondly of Fisher’s The Gastronomical Me, wherein she states that as humans, our three basic needs are for food, security, and love, and how the three are so inherently intertwined[1] and essentially inseparable. This led us into speaking about domesticity, how she’s navigating through her role(s) as a homemaker in her personal life, and how that’s seeping into her art practice. Anna’s work is marked with her frequent use of edible materials in thoughtful ways that lead these often outrageous objects to appear elegant and rather minimal. “Almost-not-food food”, as she affectionately calls them (such as cheese puff balls, candy dots, and Jawbreakers) have always led her curious, admitting that the candy aisles in her local dollar and bargain stores often catch her attention first as she finds their colours and iridescent nature so beautiful. This curiosity extends into her current fascination with cocktail cherries and sweaty cheese, mentioning that she is interested in how these foods change, sweat (and shine) over time.

Untitled pyramid, 40 x 40 x 70 cm, 2015, cheeseballs on pink IKEA crate.

Untitled pyramid, 40 x 40 x 70 cm, 2015, cheeseballs on pink IKEA crate.

The notion of labour was quite prominent throughout our entire conversation. While labour from an artistic or professional perspective is highly complex in and of itself, the majority of our talk was more so centred around domestic labour. It’s evident that there are various facets to it – whether societal, systematic, biological or self-imposed – that inherently exists more prevalently amongst women, especially when taking on and considering “domestic” responsibilities. They’re woven into our communities and day-to-day lives, carrying their own intrinsic complexities that impact us all regardless of gender. In the American artist Anne Truitt’s journal Daybook, she speaks about the familiar strain of sustaining the various demands of daily life[2] as she unpacks the numerous tasks she undertakes within her role as a mother, and how that can sometimes juxtapose with her role as an artist. Truitt also acknowledges that she feels as though doing her many duties as well as she can is essentially self-serving, as it keeps her from being angry from being away from her studio, stating that efficiently channelling her focus on household routines sets herself free for clear concentration in the studio[3]. Mentioning to Anna my immediate association with her current lifestyle and Truitt’s writing, I asked her about how she balances these roles, and about whether she felt there was or if there needed to be a distinct division between who she fundamentally is and what she does professionally or personally. I often battle with this enigmatic reality myself, so it was refreshing to hear about how Anna welcomes all her roles blending into one another, and that while there are definite challenges, in her case, the opportunities for organic collaboration between the different corners of herself prove to be worth it.

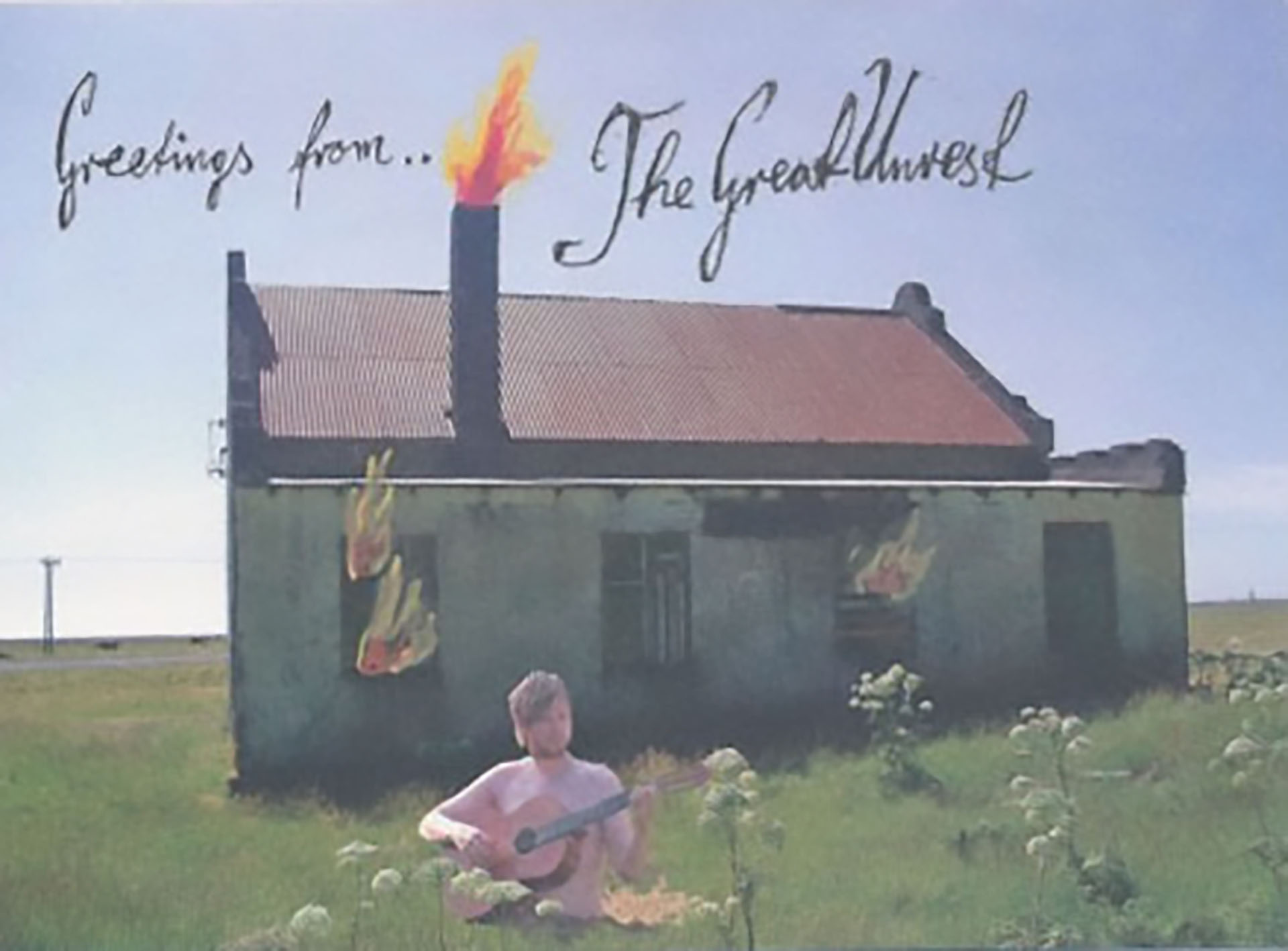

Currently working out of her Los Angeles home that she shares with her family of five, various communal surfaces, such as their kitchen and living room tables, in turn act as her studio all the same. She also spoke about walking, and how the action of walking is fundamental to her practice as a means of research, reflection and material play. From scouring the aisles of any odd store in her vicinity, to walking around the urban L.A. landscape, Anna’s work is deeply influenced by her surroundings. The generally well-tempered climate of Southern California lacks the turning of seasons, so one’s perception of time can often be questioned in these “never changing” environments. As she spoke of the opposing extremities she has experienced between the Icelandic and Southern Californian climates, her connection to nature rang clear, particularly when she spoke about Jacaranda trees. Her fondness for them lies in their ability to reveal the seasons with their blossoming. With their vibrant blossoms acting as place markers of sorts, they also imbue a rebellious quality, refusing to conform to the schedules or temperaments of other flora in their surroundings.

Jacaranda Tree on Eagle Rock Blvd.

Jacaranda Tree on Eagle Rock Blvd.

A close friend once told me that the key to sustaining art in our lives is to be curious and to always ask questions, and I believe this to be true. That said, I have never been more curious talking about commonplace things as I am when speaking with Anna Hrund. As she generously welcomed me into her headspace, I felt slightly as though I was experiencing déjà vu, getting to revisit things I thought I understood, but from another perspective. Her ways of seeing prompted me to (re)write and (re)categorize their potentials. It’s evident her understanding of these strange objects and things is intimate, which may partially come from consistently living and working so closely with them over time. The pace of her work truly lends to slowness. It was inspiring to speak with an artist with such depth and wit, as it’s apparent that her understandings surpass surface-level knowledge. Anna takes her time to get to know these objects honestly, for who they are rather than what they are, and her practice and person act as refreshing and necessary reminders to consistently make space for looking, asking and learning.

Juliane Foronda

[1] Fisher, M. F. K. The Gastronomical Me. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989, e-book.

[2] Truitt, Anne. Daybook, the Journal of an Artist. First Scribner trade paperback edition. New York: Scribner, 2013, p. 57.

[3] Truitt, Anne. Daybook, the Journal of an Artist. First Scribner trade paperback edition. New York: Scribner, 2013, p. 58.

Anna Hrund Másdóttir (b. 1981 Reykjavík) has lived and worked in Los Angeles since 2014. She holds an MFA in Art from CalArts, BA in Fine Art from the Iceland Academy of the Arts and attended the Mountain School of Art.

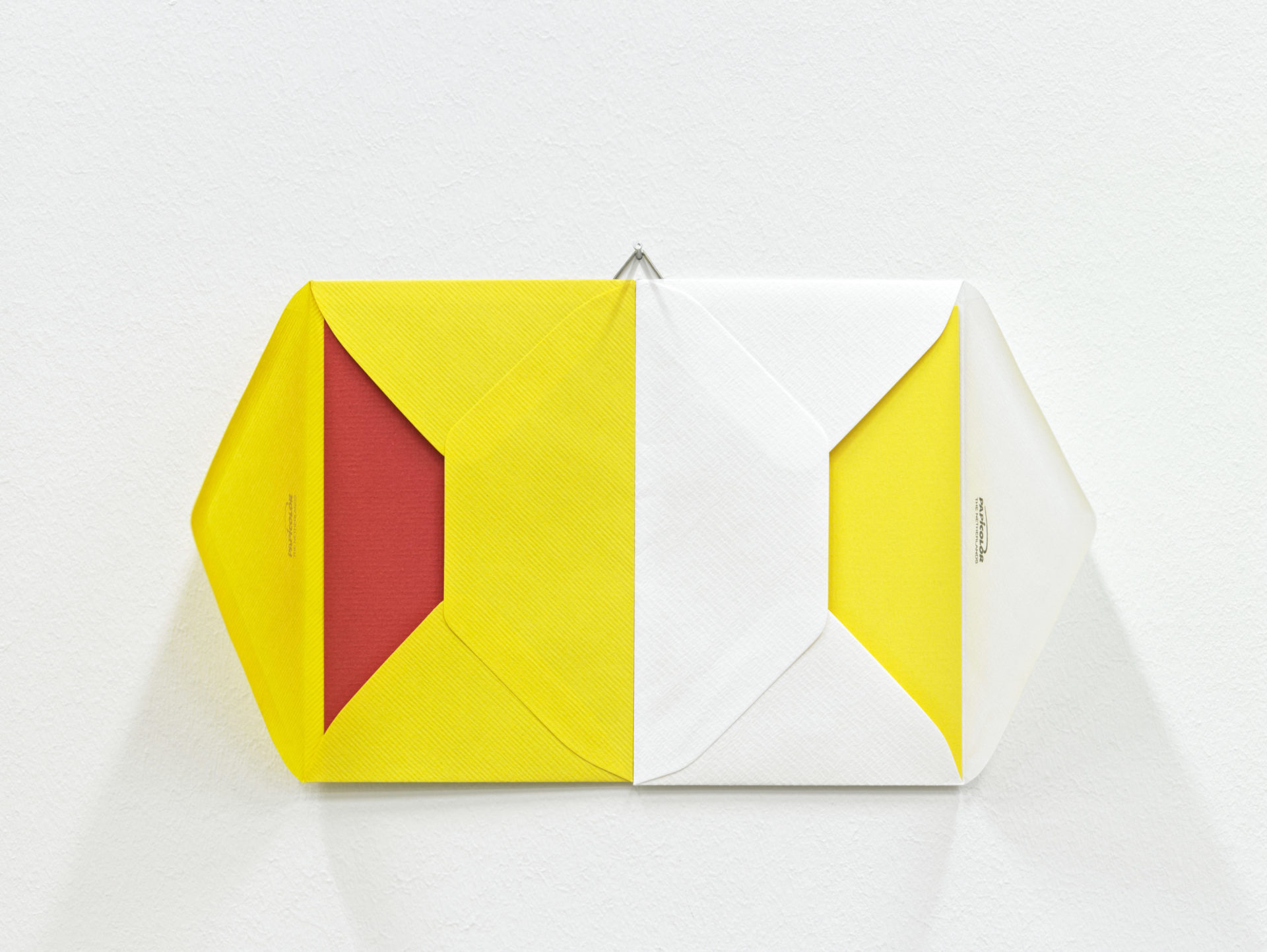

For Anna Hrund, making art is a process of discovery. Working with manufactured materials that are sometimes edible, often disposable, she combs through her surroundings while on daily routine, exploring landscapes of shelving displays, scanning a wilderness of linoleum aisles; the nature that surrounds her. What she brings to us are objects that leap out from the ordinary. She loosely assembles them, like wildflowers clenched in her hand, and brings it all as a gift; a display of findings.

Cover picture: Spongecake // Svampkaka, 40 x 40 x 15 cm, 2016. (Pepto-Bismol plaster between blue filter material)

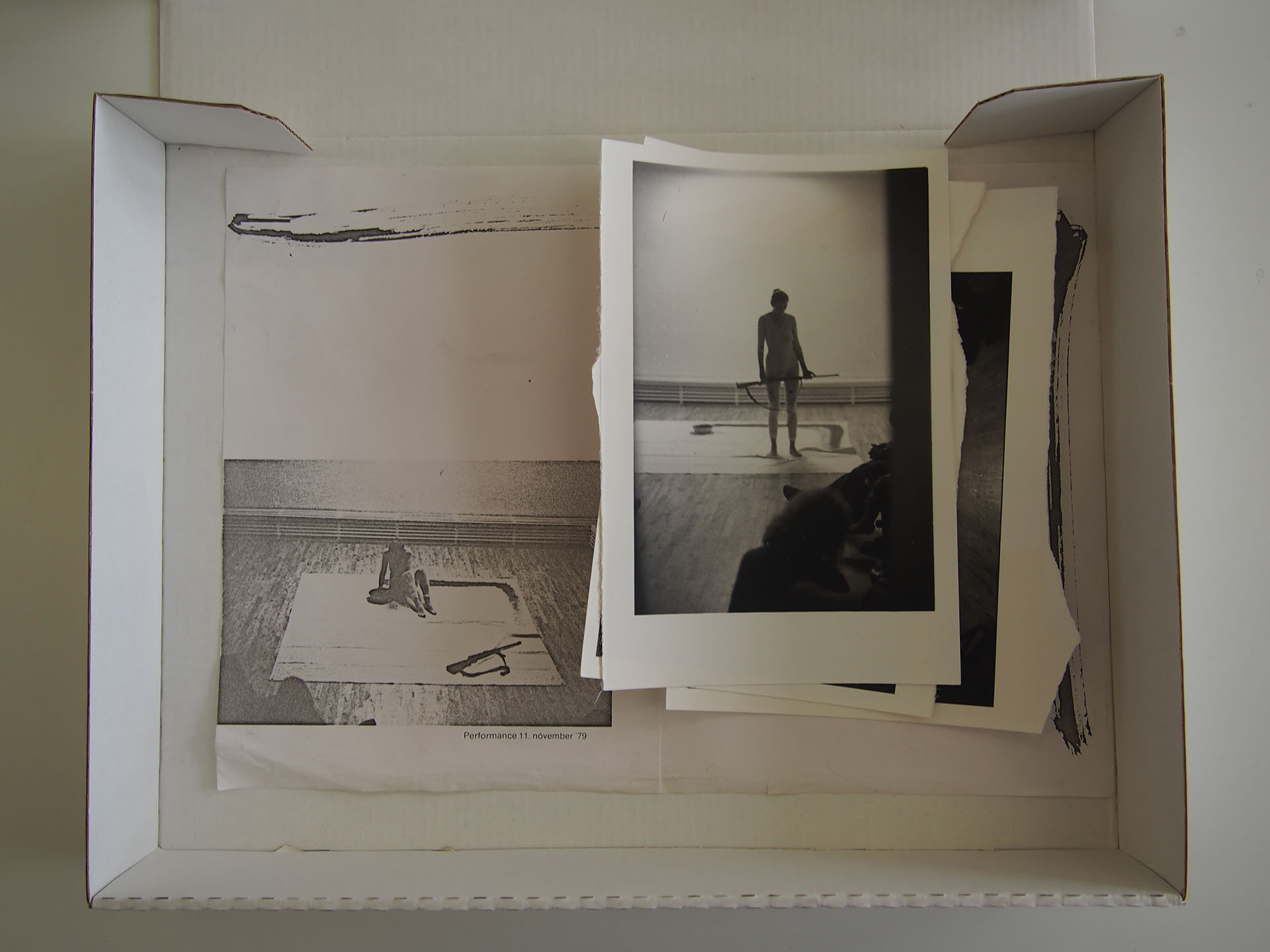

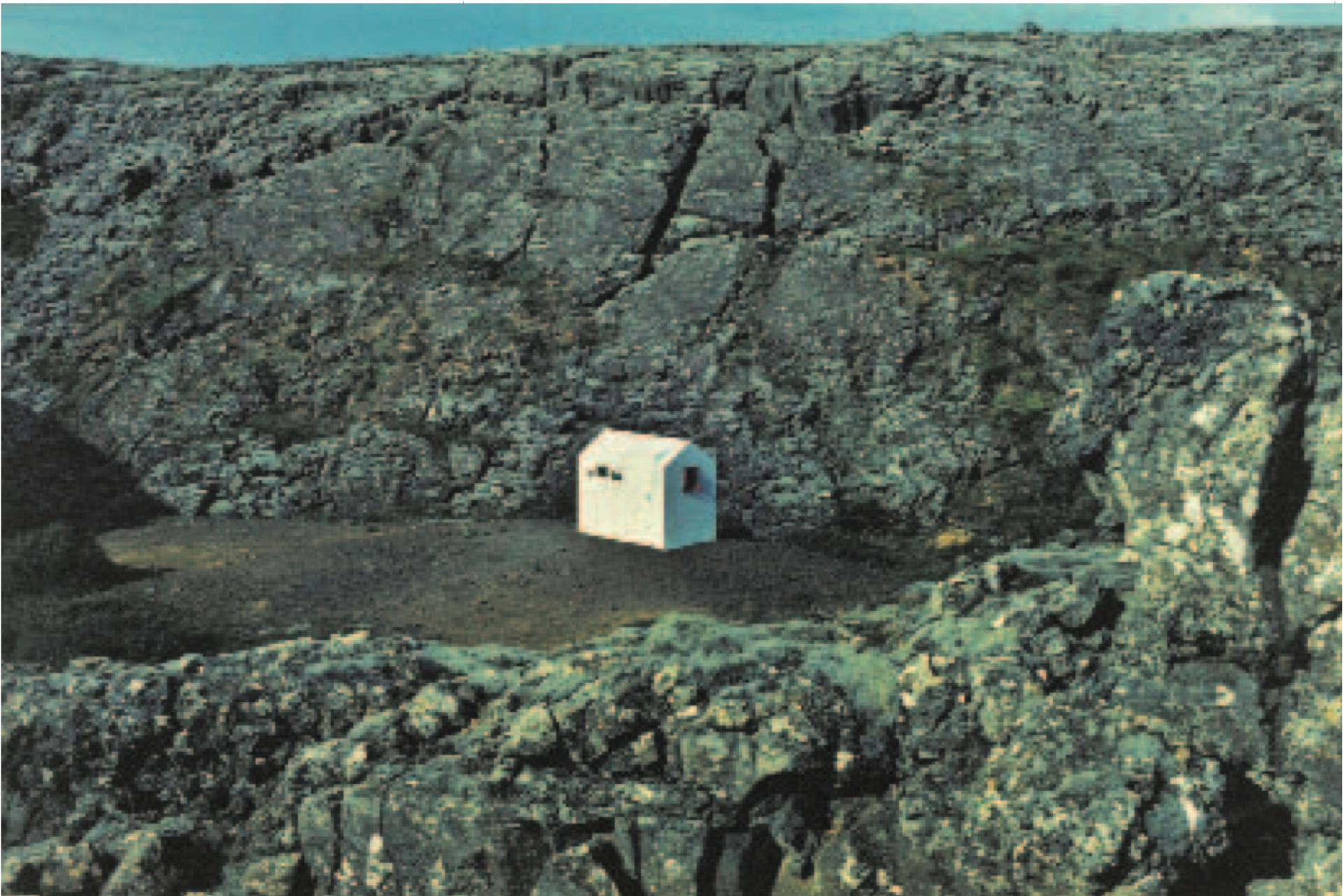

HREINN FRIÐFINNSSON A View in A (1), 1976 black and white photograph 52.5 x 64.5 cm. Courtesy of i8 gallery.

HREINN FRIÐFINNSSON A View in A (1), 1976 black and white photograph 52.5 x 64.5 cm. Courtesy of i8 gallery.

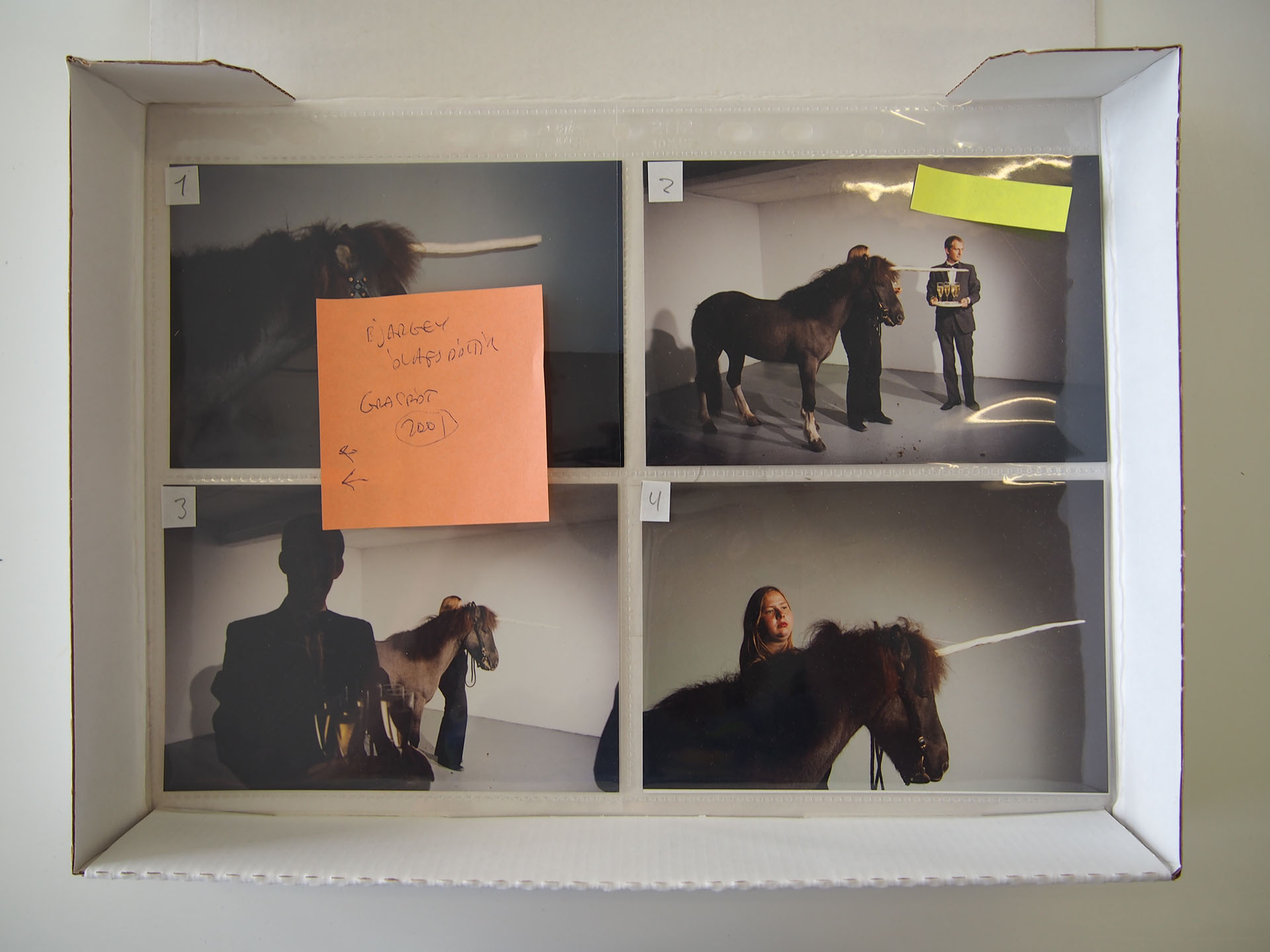

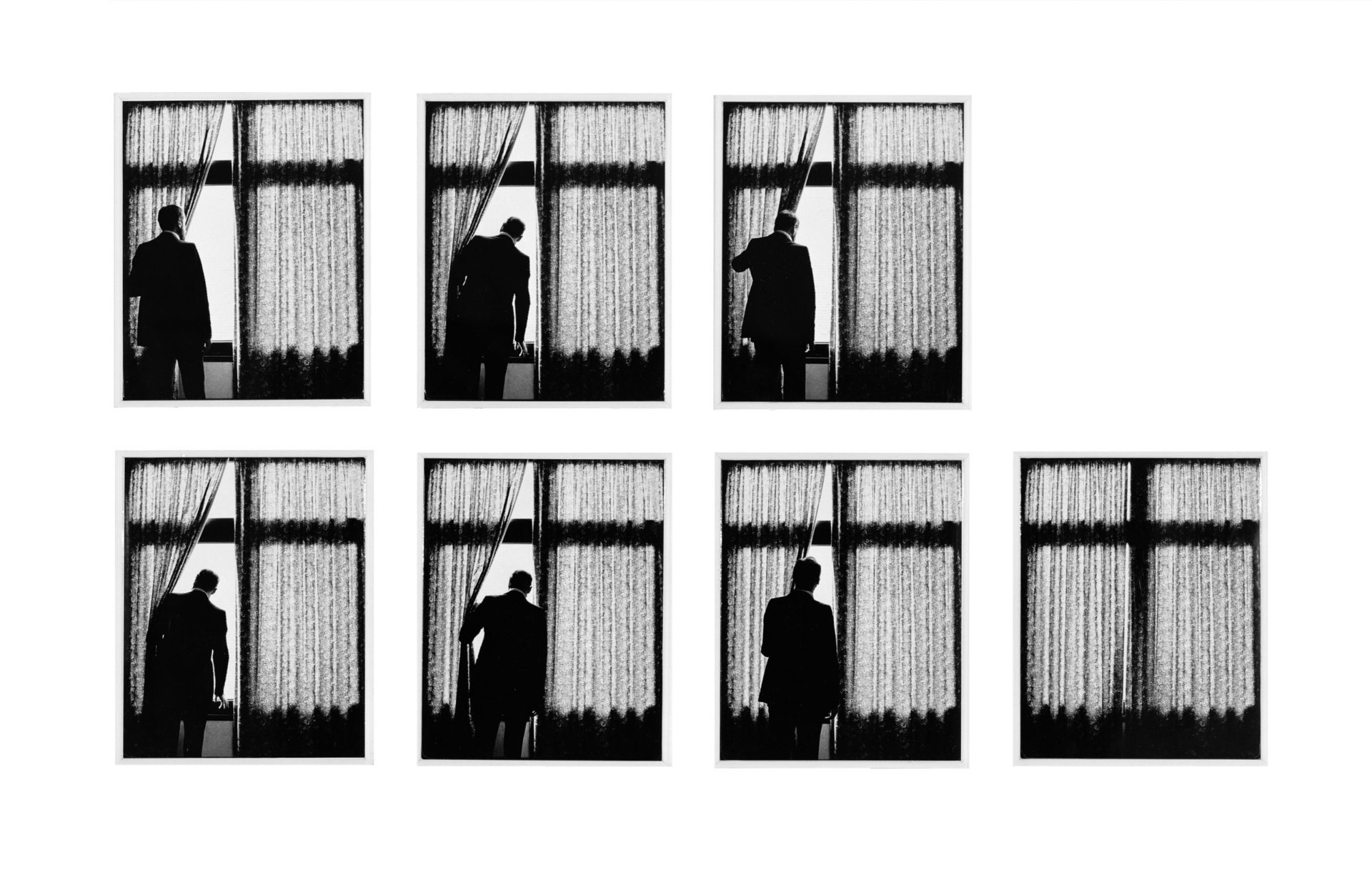

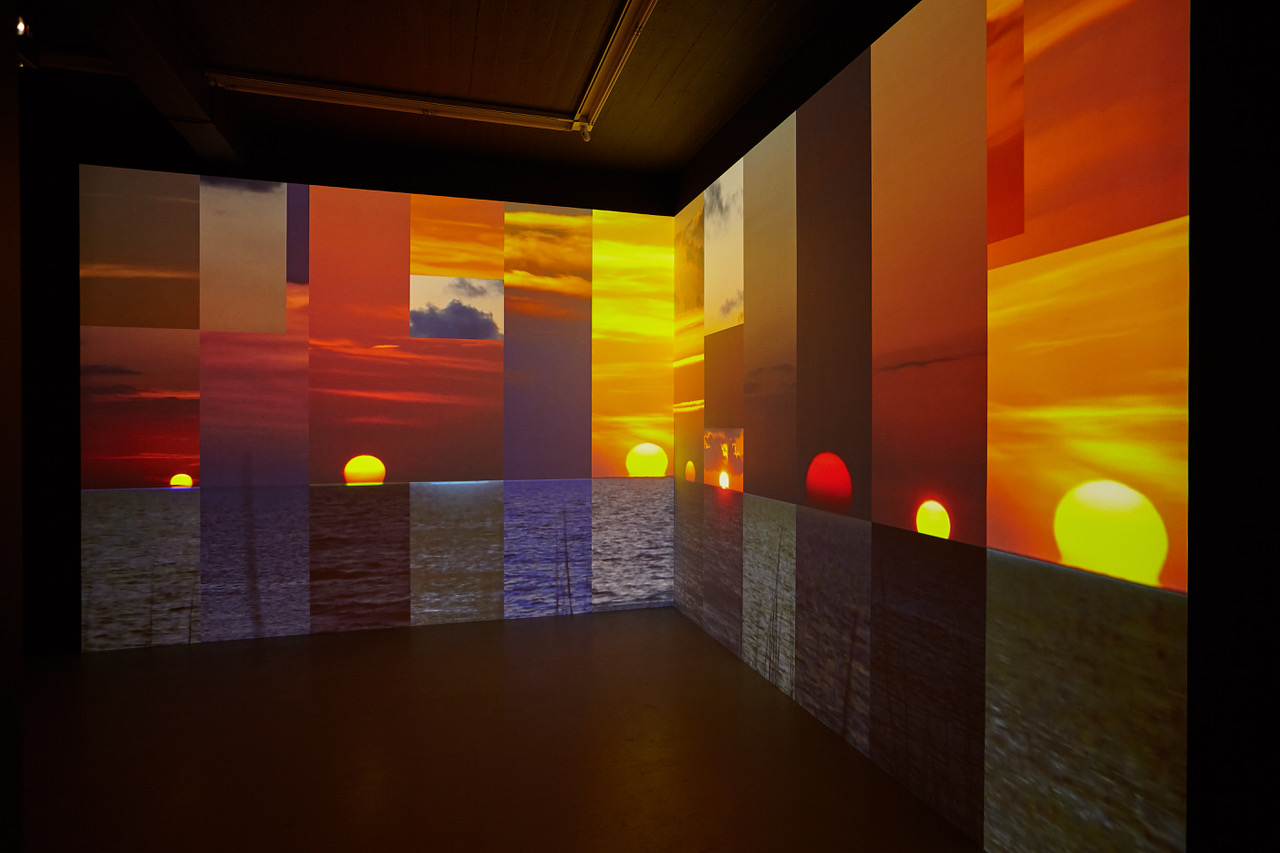

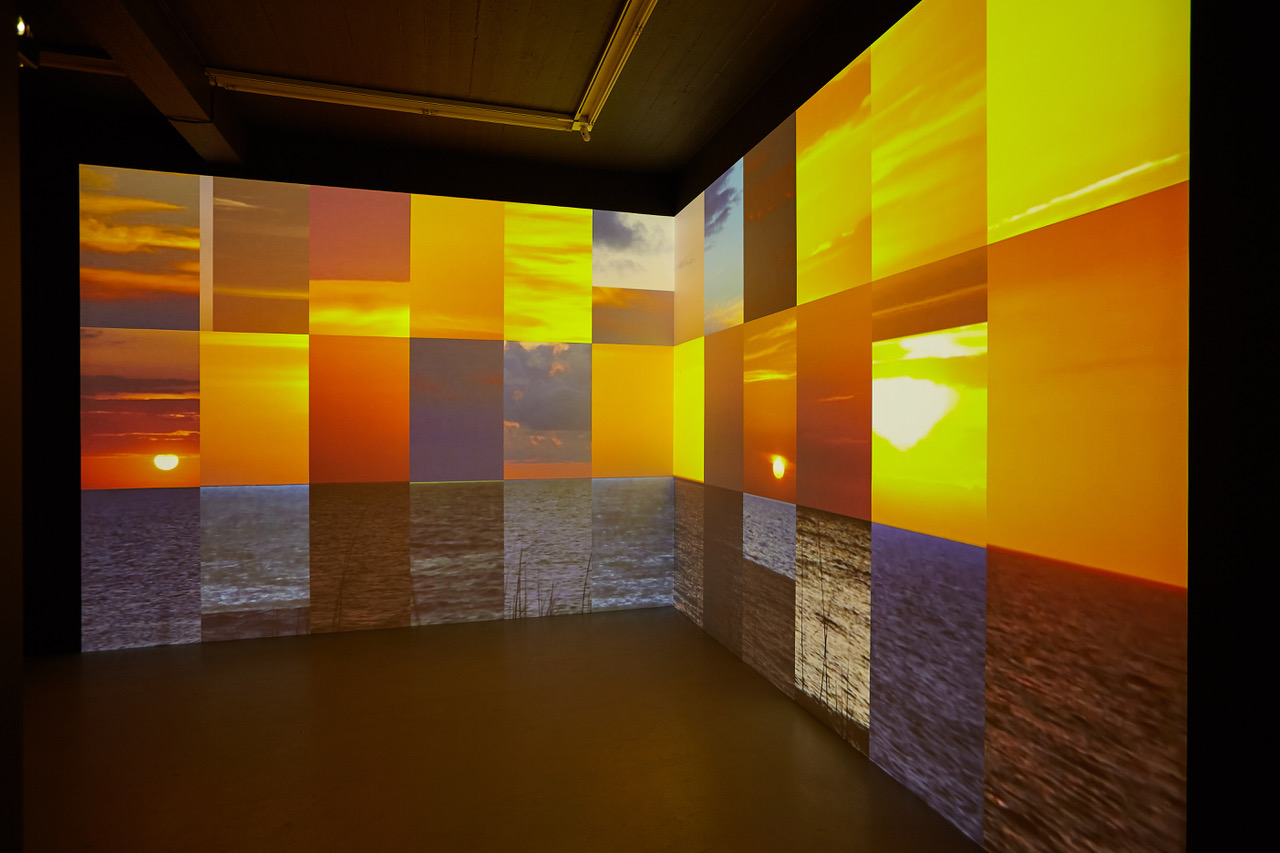

Charles Atlas

Charles Atlas