Artefacts from the restless art’s excavations

History occurs in a space between the archive and life,

between the past that is being collected and reality,

understood as everything that has not been collected.[1]

Today the Living Art Museum – Nýlistasafnið as well known as Nýló publishes and makes available to the public its performance archive. By digitalising the objects left from the performances of different artists, whether it is a proper documentation material or a crumpled note left on the floor – they invite the public to peek into their records of art “that refuses to settle”.

One of the most prevalent arguments about archives and their political legacy is based on the dichotomy of inclusion vs. exclusion. The criteria on which something is to be chosen to memorise are always a starting point of criticism. The contemporary archive of whatever nature today is criticised on the basis of representation, since by the process of choosing what to be represented – the institution is cementing a certain historical narrative. Nýló’s Performance Archive, is however in its core somewhat different from a collection based on a clear methodology of choice – it is a celebration of randomness and fellowship, that lacks any scholarly coherence. In the same time, paraphrasing one of Sol LeWitt sentences on conceptual art – the archive follows its irrational nature absolutely and logically.[2] Not a scholastic collection, rather an incomprehensible artwork, put together by artists, museum caretakers and fellow travellers, created by chance, contingency and a devotion to taking care of ephemeral matters of performing arts and preservation of memories.

The past is not “memory” but the archive itself, something that is factually present in reality.[3]

The Archive was founded in 2008 by the board of the museum. Since its foundation, some of the materials have merely been stored, but un-archived in Nýló, while others have been brought by artists to the museum.

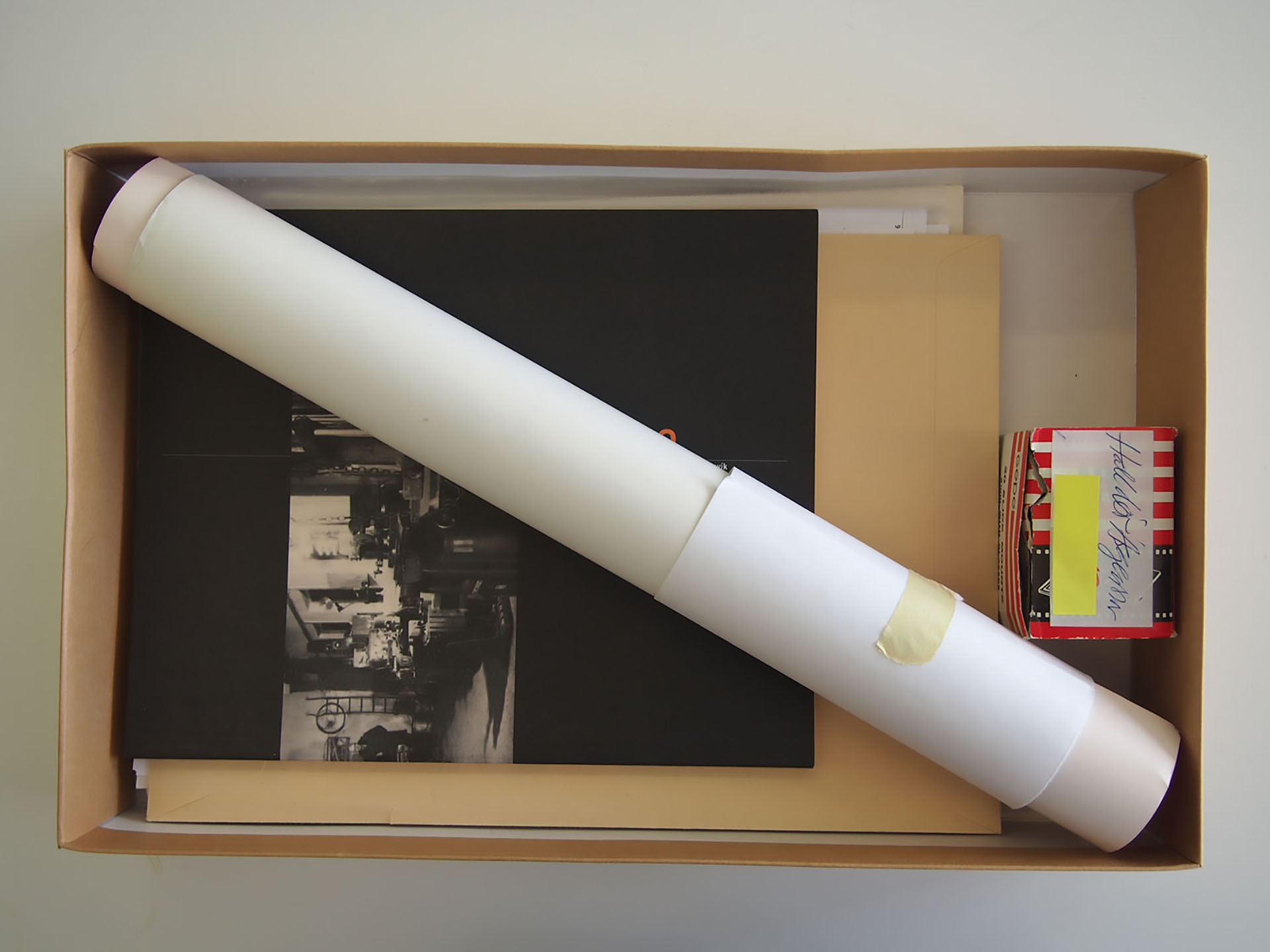

The collection of boxes, each bearing the name of a particular artist that has made a performance in Iceland (or elsewhere), in association with Nýló (or not) present artefacts left from a particular event or a context surrounding a certain occasion. If perceived as an archaeological collection, the viewer can look at it with the same eye, as one would look at drawers with ancient ceramic bits, tools and incomplete jewels remains small witnesses of craftsmanship of the past.

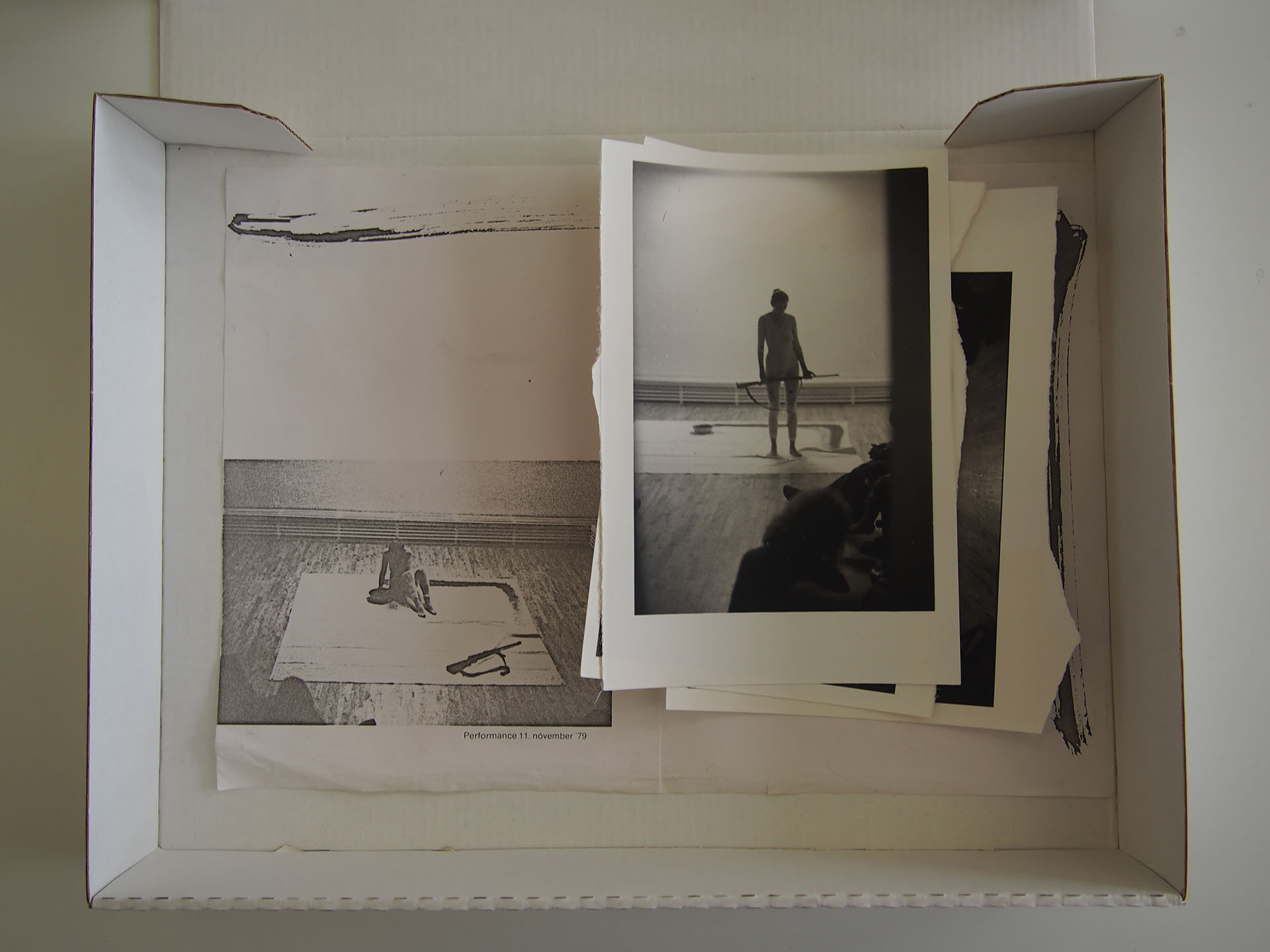

Content of Sigríður Guðjónsdóttir’s box. Photo by Ida Brottman Hansen.

Content of Sigríður Guðjónsdóttir’s box. Photo by Ida Brottman Hansen.

These objects are traces left of something that aimed to be a “disruption” of public experience, and they certainly “disrupt” the expectation of the ”archive”. No selecting, no curating, no arranging, no connecting, but a whole lot of collecting is employed as an archival tool in this work. Neither the representation of a certain taste – an attitude of the 19th-century collection, nor a modern historical museum’s attempt to represent contemporary diversity, it is a provision of care of what is left or being given. Instead of a figure of a gatekeeper typically occurring in the conversation about archives, we meet a caregiver taking care of any type of memory given.

The artefacts and documentations are left in 60 separate boxes named after Icelandic and international artists such as Ásta Ólafsdóttir, Ásdís Sif Gunnarsdóttir, Bryndís Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir & Clare Charnley, Sjón, Ragnar Kjartansson, Nam June Paik, Myriam Bat-Yosef, OXSMÁ, Bruni BB, Halldór Ásgeirsson, Hannes Lárusson, Karlotta Blöndal and many others. Viewers are invited to glance at the content of the boxes – photographs and scans of the objects. There are two elements of the archive: a lineage of occurrence of historical events and the collection of artefacts of an archaeological type. Typically, the two narratives operate simultaneously and independently, but in this case, the second dominates the other.

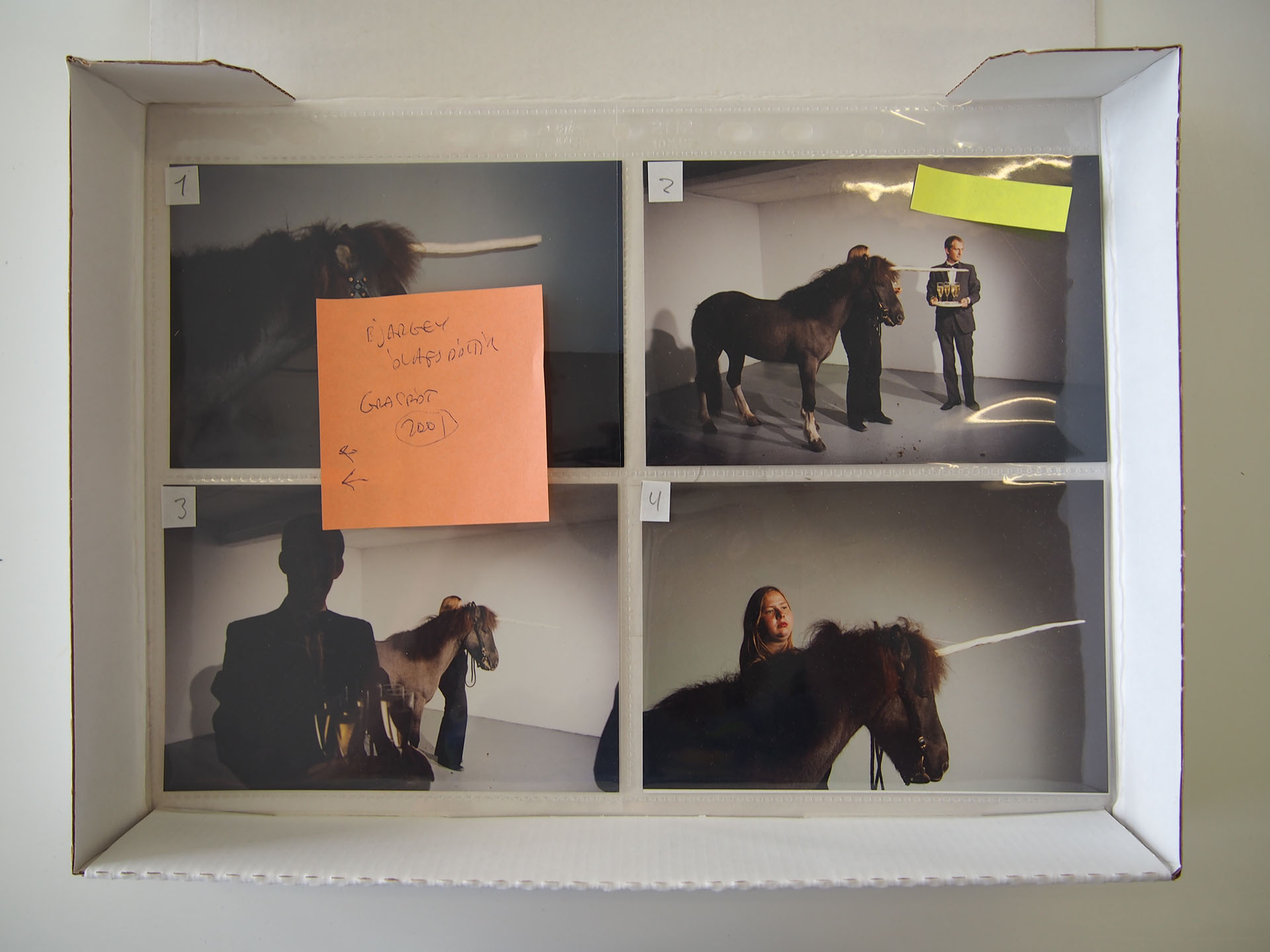

Content of Bjargey Ólafsdóttir box. Photo by Ida Brottman Hansen.

Content of Bjargey Ólafsdóttir box. Photo by Ida Brottman Hansen.

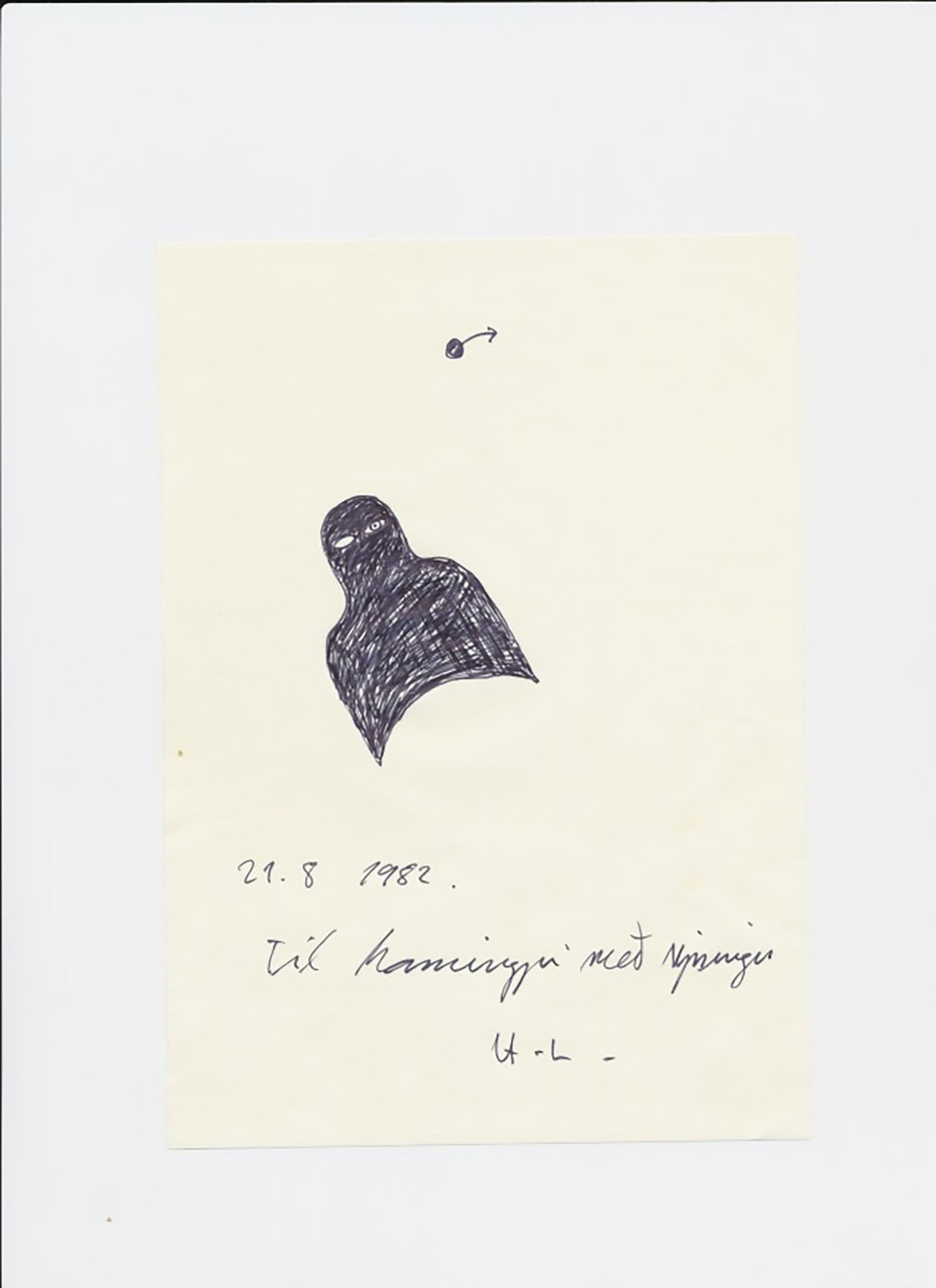

Artefact from Hannes Lárusson’s box.

Artefact from Hannes Lárusson’s box.

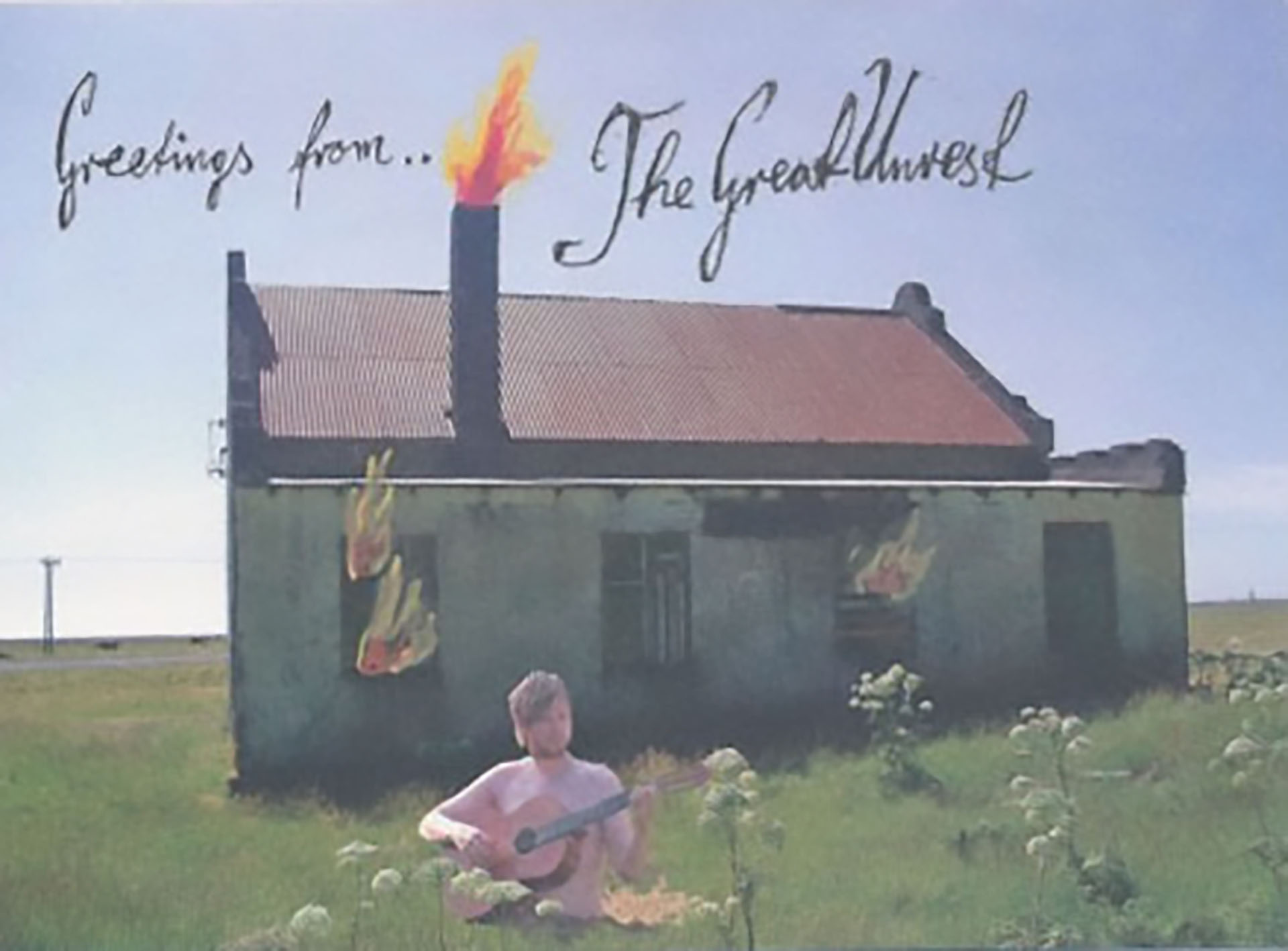

“Something moving around slowly wrapped in a white cloth, maybe a sick train conductor”, says on an old yellow page with a small sketch of “something obvious” found in Ásta Ólafsdóttir box together with a cassette tape named “Ásta Ólafsdóttir songs”. Neatly stored in plastic files, images portraying Bjargey Ólafsdóttir horses, playing unicorns with glasses of sparkling wine. A black and white photograph of a man in a soaking wet costume with a bow and white gloves leaving the seaside in Lars Emil Árnason’s box. A letter that shouldn’t be open by anyone but the museum’s current collection manager in case there is no way to play an audio file by Örn Alexander Amundson. A photograph, a postcard with greetings sent to the Reykjavik Art Festival by Ragnar Kjartansson in conjunction with his performance “The Great Unrest” – “The three weeks performance done in the abandoned theatre/dancehall Dagsbrún”. Scribbles and notes – “references about and after performance at NYLO”, a lady’s magazine cover FRUIN from 1963, which backside asks the readers if they have children as well as telling the names of participants of the performance “The Beginning of the Country Band – The Funerals”.

Artefact from Ragnar Kjartansson’s box.

Artefact from Ragnar Kjartansson’s box.

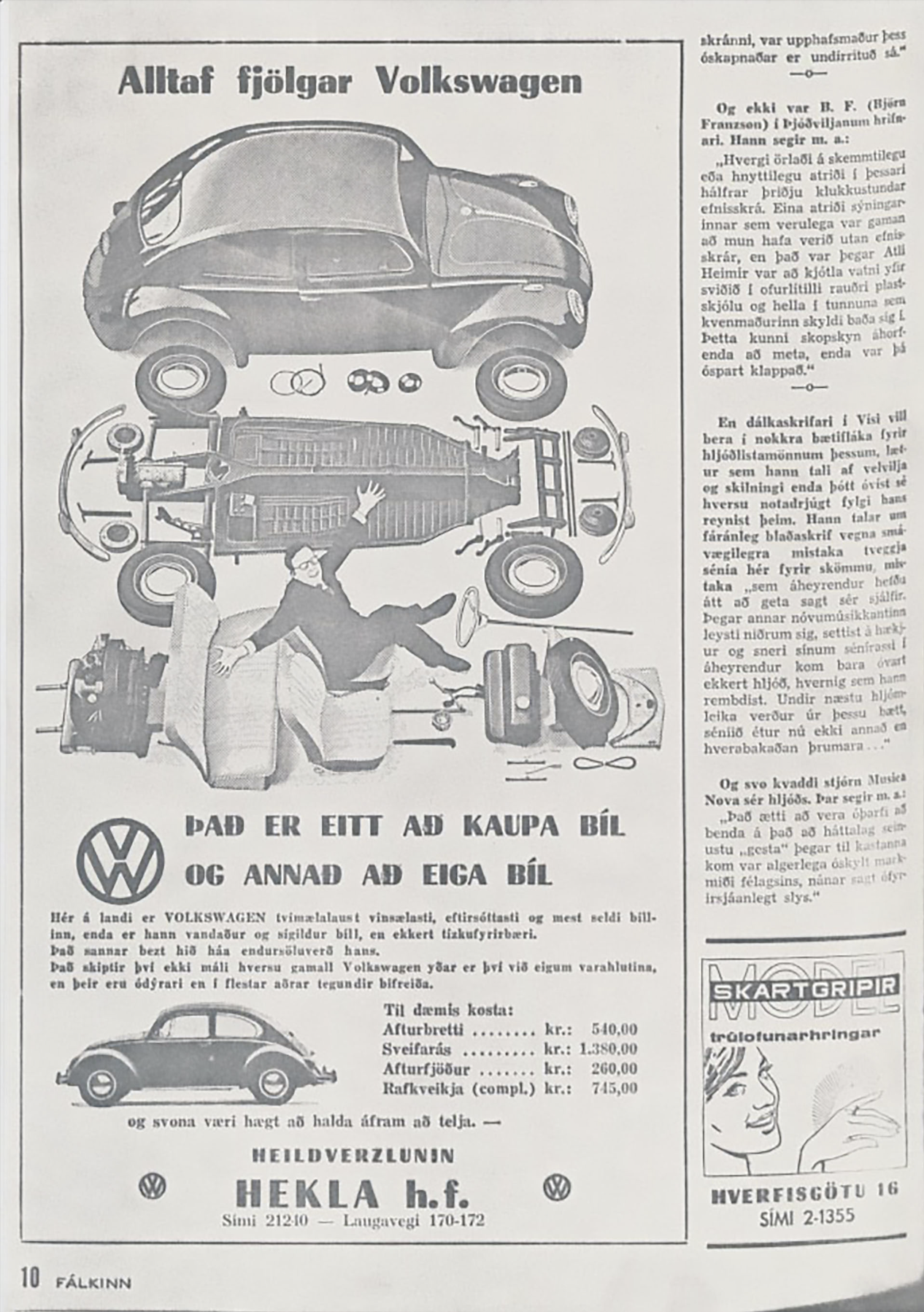

In the box named after Nam June Paik the visitor finds newspaper clippings from the magazine Fálkinn from 1965, connecting us to the story described by Joan Rothfuss in his book Topless Cellist: The Improbable Life of Charlotte Moorman. This incredible story is about the difficult life of the composer association Musica Nova, stuck between the irrepressible movement of Fluxus and the all so decent Icelandic public. The artist Dieter Roth, living in Reykjavik connected his friend Nam June Paik with Musica Nova, an association of composers and musicians, whose main goal was to introduce modern music to the Icelandic public. The association invited Nam June Paik together with cellist Charlotte Moorman, and arranged a concert in Reykjavik, throughout which the following were shown and played in different inventive ways: striptease, water barrels, shaving cream, pistols, dropped pants and so on. As a result of the memorable evening, Musica Nova was denounced and felt compelled to publish an open apology calling the concert „an unforeseeable accident.“[4]

Fálkinn magazine page from Nam June Paik’s box.

Fálkinn magazine page from Nam June Paik’s box.

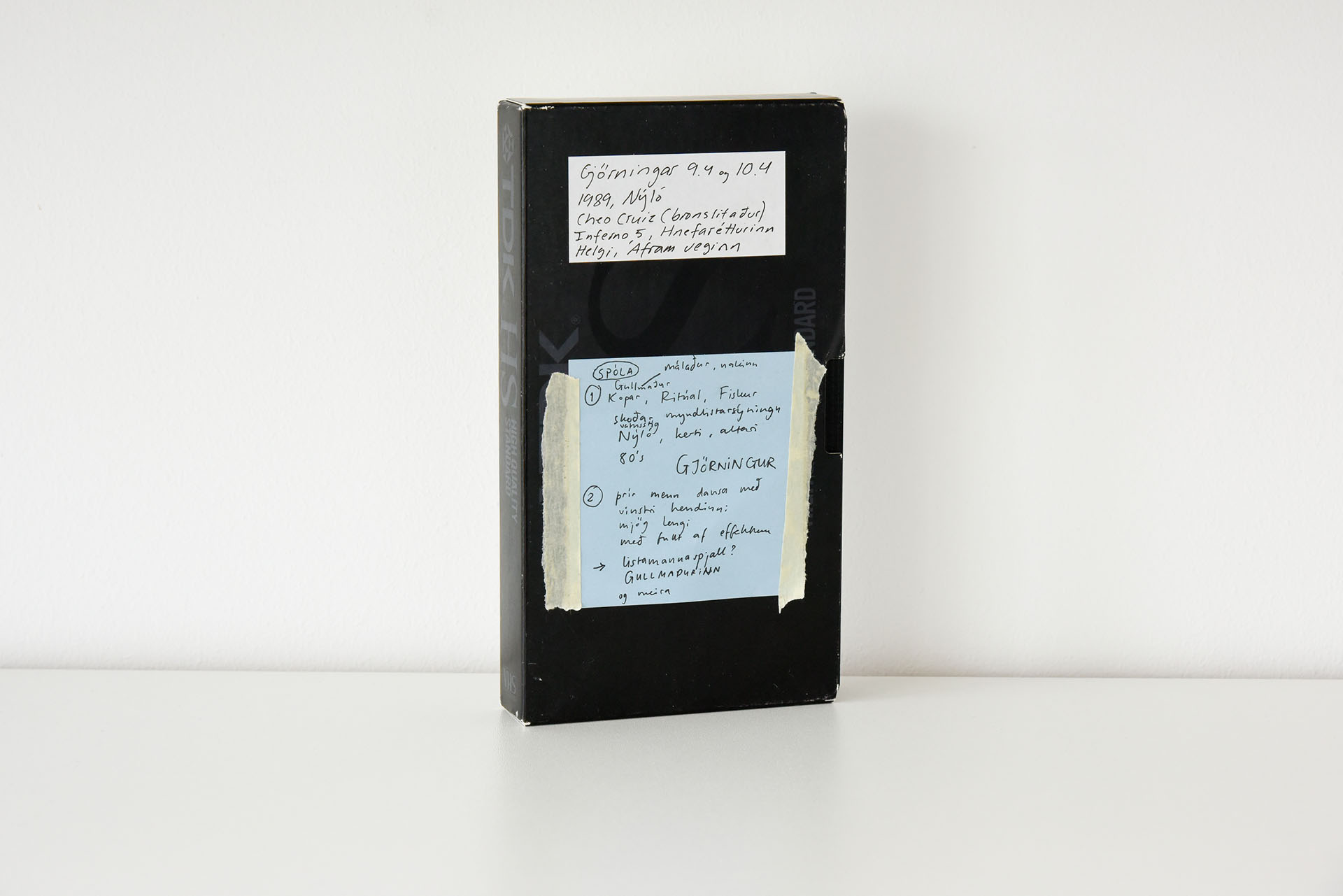

Another hidden gem of this collaborative collage of beauty and the absurd, is placed in a box named “Recordings of performance evenings”, which is a collection of video documentation of a performance evening that took place in Nýló. On the taped-over VHS cassette through the glitches and noise, follows one after another: a naked golden man walking a dead fish around the gallery, three men in black twirling wrists of their right hands in a synchronized manner, a person driving an imaginary car in the light of a projector, and two artists asking one another “why do you make your art here in the most poor country of art in the world?”. The recording ends with darkness, and through smudged visuals of a 1979 screening by The Icelandic National Broadcasting Service, emerge the quarrelling characters of the soap opera “Dallas.” This unintended relation, the small accident of the taped-over VHS, creates a very specific sequence, where the proximity of the cultural extremes on one tape, is both absurd and typical to Icelandic contemporary art throughout its history.

Photograph of VHS with „Recordings of performance evenings“.

Photograph of VHS with „Recordings of performance evenings“.

The equation of the mundane and the sublime, significant and vulgar could give it a status of exceptionally democratic art – which ironically stands untouched by the major political trends going through today’s European art striving for democracy. Those trends are vividly present in the rest of Scandinavia, shaped by the current form of identity politics and distinguished by missionary didacticism, trapped in its ambition to create great social change or represent a political critique of the strong partisan kind.

Whether in opposition to them or in oblivion, many artists in Iceland instead take on a different role: that of a holy fool, elevating the trivial, the boring and the unbearable, transforming them into beautiful sights full of consolation, where irony is a prerequisite for the magic beam to work. The Performance Archive, just as some of other NYLO’s projects are no exception. It escapes both academic formalism and the obscure context of the discourse of International Art English[5], it is instead telling us magically unexpected stories by picking on the seemingly small and unimportant, freely roaming on the grazing lands of the past.

Maria Safronova Wahlström

[1] Sven Spieker, Boris Groys: The Logic of Collecting, ARTMargins, January 1999,

https://artmargins.com/boris-groys-the-logic-of-collecting/)

[2] Sol Lewitt, Sentences on Conceptual Art, Art-Language England, Vol.1, May 1969, p.11

[3] Sven Spieker, Boris Groys: The Logic of Collecting, ARTMargins, January 1999,

https://artmargins.com/boris-groys-the-logic-of-collecting/

[4] Joan Rothfuss, Topless Cellist: The Improbable Life of Charlotte Moorman, MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusets, 2014, p.121

[5] Alix Rule and David Levine, “International Art English”, Triple Canopy,

https://www.canopycanopycanopy.com/contents/international_art_english

Cover Picture: Content of Halldór Ásgeirsson’s box. Photo by Ida Brottman Hansen.