The Drumming Beat: Daníel Magnússon at Hverfisgallerí

The Drumming Beat: Daníel Magnússon at Hverfisgallerí

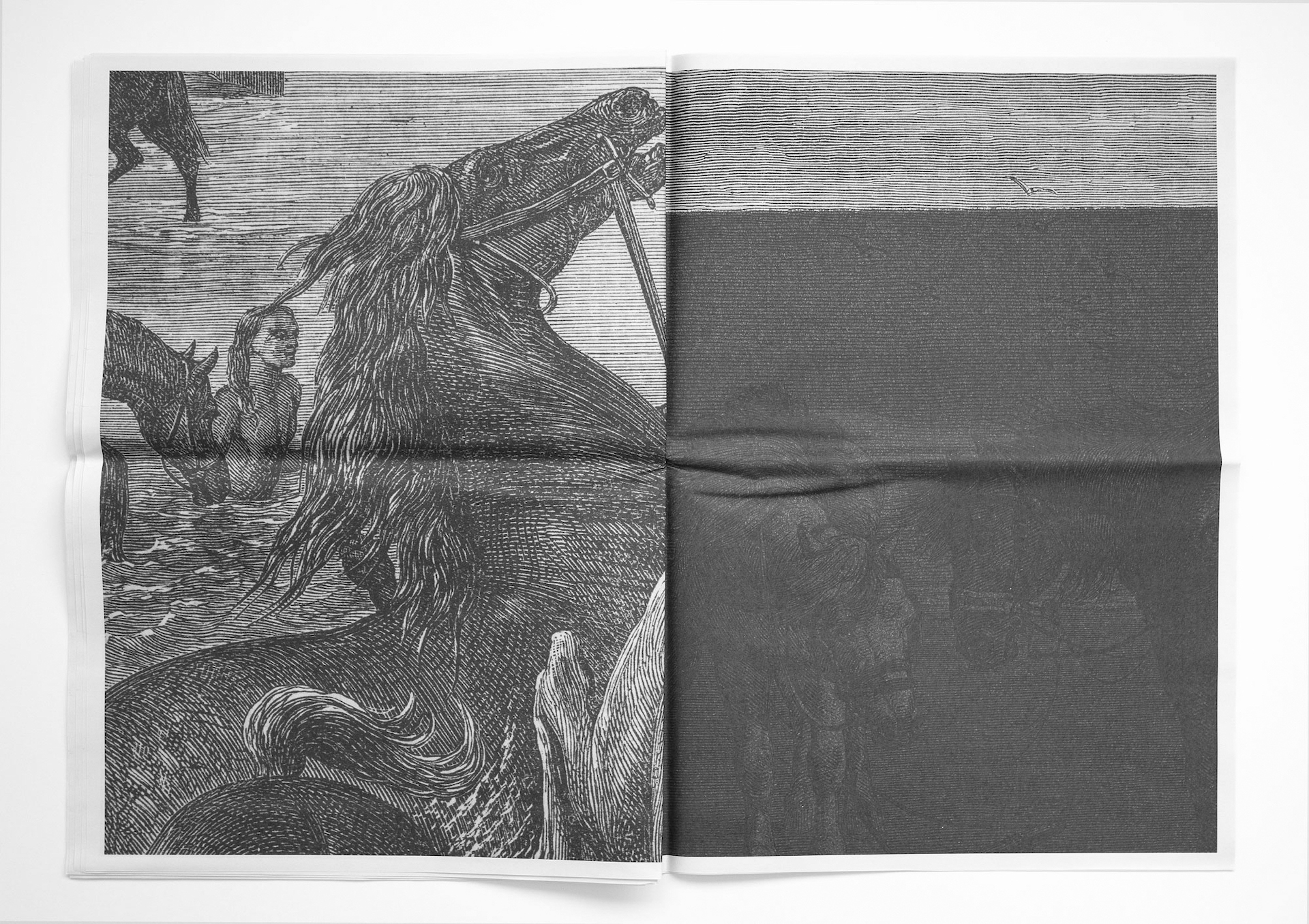

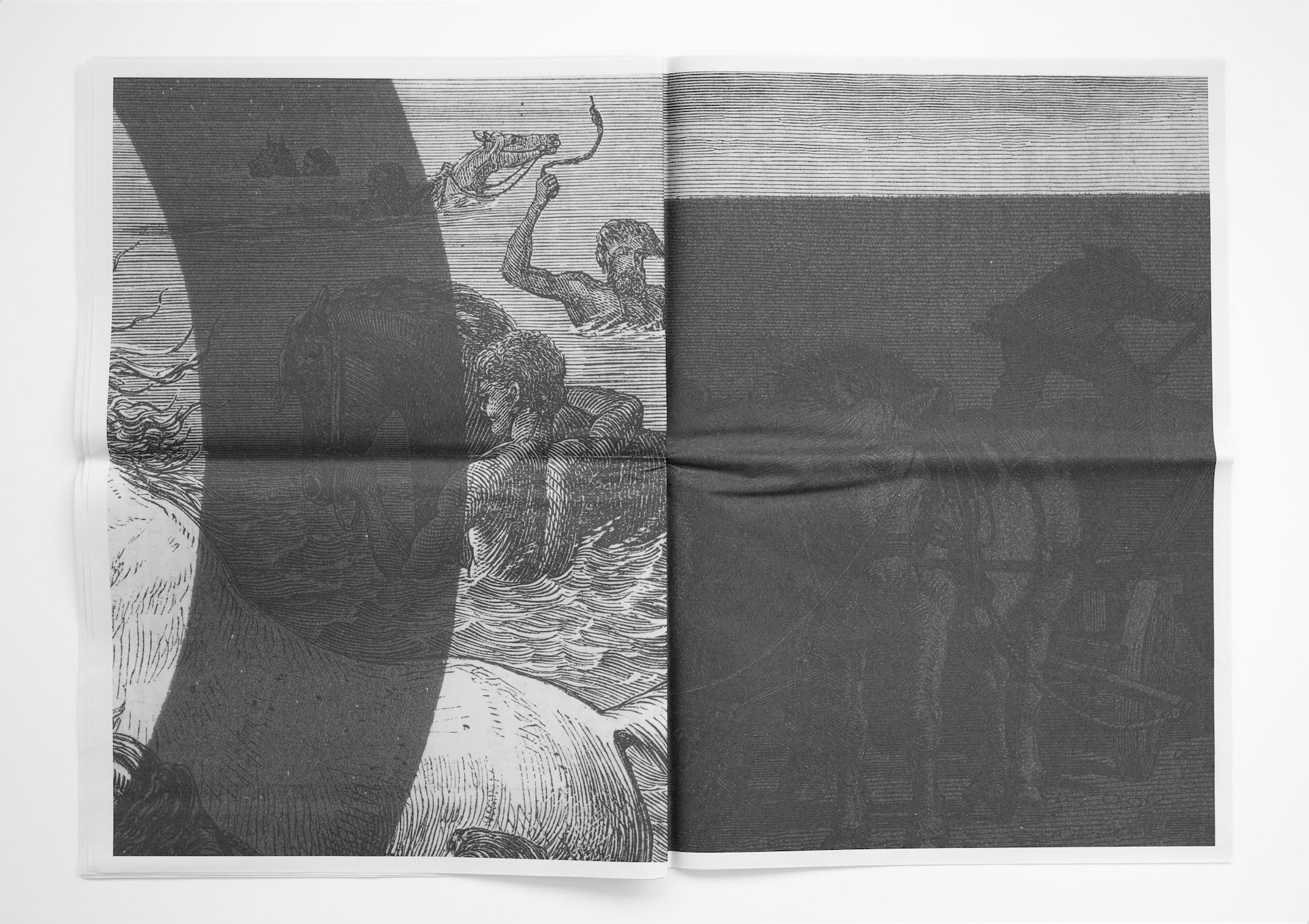

Daníel Magnússons´s exhibition TRANSIT at Hverfisgallerí explores a rhythm of detail, depicting images of close up angles and geometrical forms created out of seemingly everyday moments and objects. In this way Magnússon´s photographs examine how construction and composition can inform the unfolding narrative an image creates, focusing in on the minutiae of a meaningful moment. The relevance of the frame, the subtlety of a directed narrative, and the power of an image seemingly “empty” of meaning: I interviewed Daníel to delve deeper into these thematics of his Hverfisgallerí exhibition.

I was curious how photography informs his practice, an artist that works in many mediums and is trained as a sculptor. What does the medium of photography allow him?

DM: I am not sure that I can answer this question, actually it is not a possibility so to speak. I have worked with photographs for a long time and I have spent a long time as well discussing this media with other artists and professional photographers. Much of the work I did before educating as a sculptor in the eighties was in portrait and landscape. I tried out different media and built a small darkroom everywhere I lived. I did a lot of darkroom work in those years and extensive work in experiments with different media and different equipment. But none of this made it convenient to choose this line of work. When I look at some of the photographs I shot in the eighties I am actually surprised. I did work in sculpture for over a decade or so and it was fascinating, it had all the convenience that I needed. But still it was not enough. The voice today is different from what it sounded three decades ago. This voice knows a lot and it has tried different things. It has lost various battles and won some others. I think that what everybody has to focus on is waiting.

If I would have an answer for you regarding this question it would be the art of waiting. I guess I was lucky that I never intentionally decided to work in this field, it kind of happened after a period of a long waiting.

Daníel tells me that the works in this exhibition are contextualized by a main idea he calls:

“… the closure of the frame and the field it spans. It is what I have described as a sufficiently meaningful or true frame. That is all the entities that are necessary for the frame to be true …”

Cleverly angled shadows on concrete, the appealing corner of a teal swimming pool, a humble wooden piano, a vibrantly curved kiddy slide, a satisfying ceiling curve and suggestive red curtain. These tightly composed shapes have a satisfying body and movement, curvature and liveliness to them. They are pleasing in their invocations, containing elements of playfulness in color, connotations of the domestic, everydayness, childhood, and a simplicity of experience.

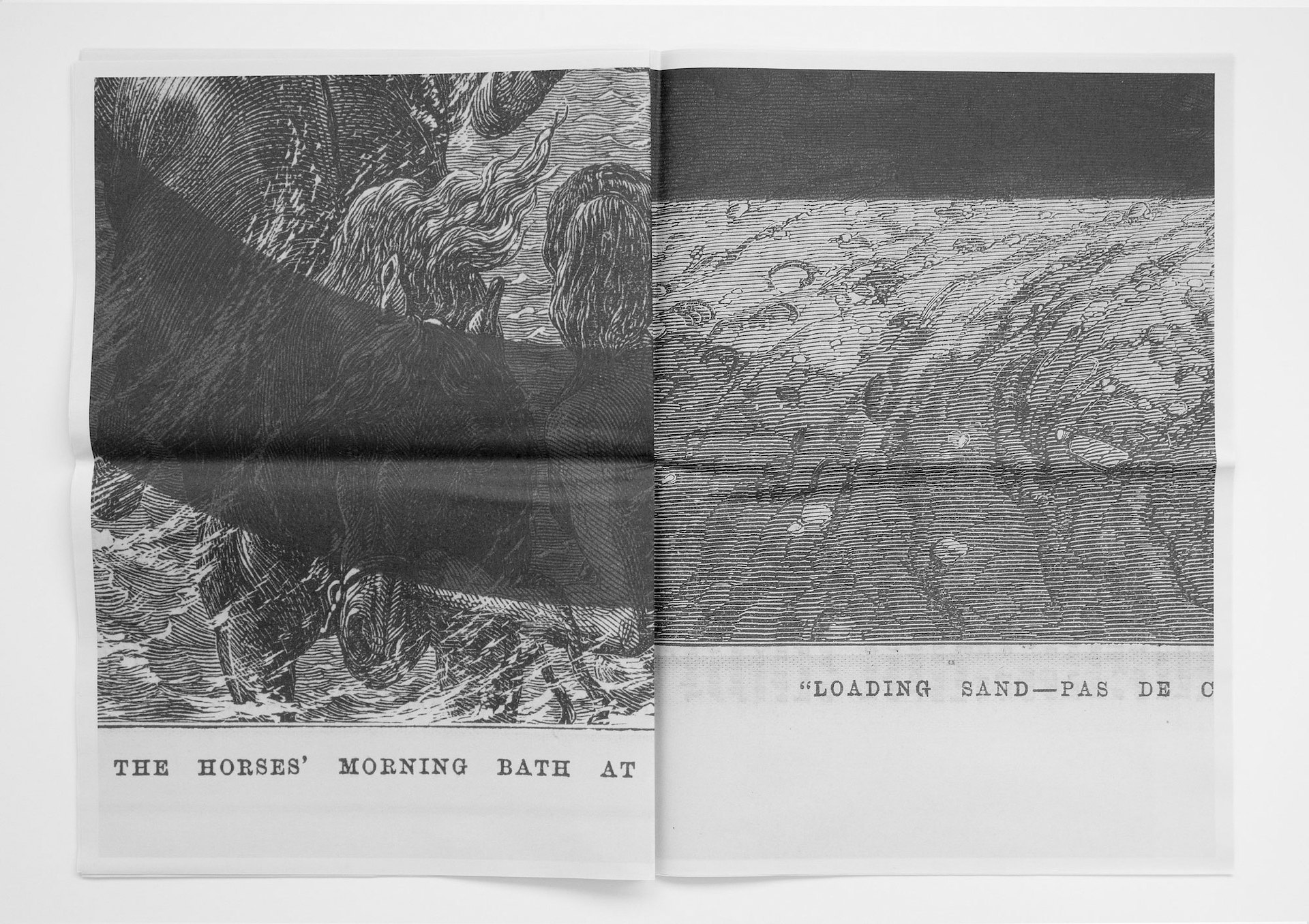

Sadsong, 2015, inkjet print on 320 gr Sihl Masterclass cotton paper, 92 x 92 cm.

Sadsong, 2015, inkjet print on 320 gr Sihl Masterclass cotton paper, 92 x 92 cm.

In terms of his artistic influence, Daníel explains that in his practice he doesn’t necessarily draw inspiration from specific favorites or names, searching rather from what he calls his “silent drumbeat”:

“… I do work in separate fields. Street and elsewhere, which would be street-life. It is a fraction of my collection and portraits as well. I have a different approach to those brands. I tend to search for what I call the ‘silent drumbeat´ in forms and patterns. Maybe it sounds awkward to describe it this way but it really is the fact.

I have never been able to create or bring forward anything of artistic value by deciding to do so. It usually takes a good walking distance. For me it is partly being superstitious and eccentric.

What seems to be a normal day is usually not, when you take into consideration all the arbitrary variables that can change. I do a lot of walking and not necessarily to ‘find´ something. If I have a camera with me, much of the time and effort is carrying it.

I admit that some of the walks do not bring any fruit so to speak. My interest, for the last few years is mostly under two feet from the ground and patterns in the human-nature ambiance. My work is in following and searching. What I am interested in must be equivalent to what you see in the most precious tapestry. It has to be valued and treated as a cherished truth. There is a quotation from a well known scientist who said that you will only understand nature through admiration. Maybe the thing is that I was brought up on farms, and I used to work on farms as a young boy and through my teenage years. I had the whole picture and it was narrated with smell from soil, grass, blood and rotting flesh. The colors and smell of the tundra, it’s a whole unified kingdom with a low pitch voice, a drumbeat…”

His images appear seemingly “neutral”, in their lack of specific reference, and yet this absence does inform a specific direction or motive in the work. These small moments all contain some sort of connection, emotional response, ingrained in us and our unique experiences. Like Daníel describes there is this certain tempo to his photographs, this drumbeat as he terms it, that informs our continued interest and curiosity.

DA: Why this focus on the aesthetic of seemingly background, irrelevant, uncertain landscapes?

DM: Aesthetic is an ambitious word. I try to avoid circumstances where I can be tempted by the atmosphere of aesthetics. Probably one can not escape the weight or gravity of that term – yesterday’s aesthetics are today’s cosmetics, a postmodern cliche. I probably do tend to build my work from an apocalyptic approach to classical aesthetics, my education was. We made statues and pictures and we travelled in Vineland. This attention to photographing something in which there is no event, no momentum, no specific purpose.

DA: What did you want people to experience in this exhibition, the lasting emotion or thought?

DM: There is a purpose and there is an underlying narrative. The silent drumbeat is the decoy, and when you understand that it is not separable from the narrative you surrender to the grace of that particular frame. That’s my personal belief. It is not like it happens all the time, but when it happens, it is perfect and you don’t know why. I do want viewers of my work to experience my beliefs. That they can see or submit to my vision, which is quite arrogant.

Daria Sól Andrews

Daníel Magnússon´s exhibition “TRANSIT” is on view at Hverfisgallerí until May 16th, 2020.

https://hverfisgalleri.is/exhibition/transit/

Photos courtesy of Hverfisgallerí and the artist.

Courtesy of Hafnarborg.

Courtesy of Hafnarborg. Gerðarstundin (e. ‘Gerður’s Workshop’). Courtesy of Gerðarsafn.

Gerðarstundin (e. ‘Gerður’s Workshop’). Courtesy of Gerðarsafn. Courtesy of Hafnarborg.

Courtesy of Hafnarborg.