Entering Nýló I see a large clock, colorful drawings for musical scores, crumbling plastic containers, meticulously crafted bodies and utopian visions that explore what’s ahead by touching upon our modern and possible not-so-distant future positions, identities and situations. I sit down with curator Sunna Ástþórsdóttir and artist Rebecca Erin Moran for a talk which took the theme of innovation as its starting point to speak about the more personal anxieties of contemporary artists and the agencies that the arts have in our current political landscape. …and what then? Is Sunna’s curatorial debut with Nýlistasafnið, she has been studying and practicing art theory and curation in Denmark for the last eight years. Rebecca Erin Moran is an American/Icelandic artist currently living in Berlin.

The exhibition gathers a handsome roster of artists: Andreas Brunner, Eva Ísleifs, Freyja Eilíf, Fritz Hendrik IV, Huginn Þór Arason, Libia Castro & Ólafur Ólafsson, Rebecca Erin Moran, Rúna Þorkelsdóttir, Steinunn Gunnlaugsdóttir, Thorvaldur Thorsteinsson and Þórður Ben Sveinsson.

B: The first thing I noticed when I walked in to Nýlistasafnið was a peculiar atmosphere. I somehow felt an immediate connection to science fiction. Was this intentional?

S: The exhibition looks to the future and I think it’s a natural step to move into science fiction when it comes to speculating things to come. The overall theme is glancing at things approaching us, how to approach them and exploring areas which are unknown to us at this date. We’re dealing with concepts of innovation, foretelling and poetically exploring what may or may not happen in our not so distant future.

B: To me, the large painting by Þórður Ben seems to have the strongest or most literal connection to sci-fi. It depicts a temple-like architecture surrounded by dreamy meadows and a utopic landscape bathed in Icelandic summer light. Here we are proposed with an escape from reality in favour of something greater. Could you tell me little bit about how this work came to the show?

S: Þórður’s painting has that approach for sure. It imagines a place which could very well be derived from a science fiction novel. With all of these artists, dealing with the future has to do with each of their intentions. This painting, for example, is from 1983, and I believe that looking towards utopian futures seemed like a brighter vision at the time. Today it seems like a far out dream, because the end of earth is becoming increasingly more feasible to us. Those who understand it do everything in their power to protect while for many, the future is too dark or hopeless to see these utopian, alternative realities. On the other hand, the utopian vision seems to feed into younger generations of artists. Fritz Hendrik IV brought two paintings to the show which depict similar scenarios, but imply more of a dune-like, outer-space scenario. The human is still present in his portrayals, and like Þórður, there is a craving to escape the instability through the making-of a possible world.

R: I think innovation links to sci-fi, and it ultimately connects to creating the spaces where something new can happen. It reminds me a bit of the Dialogues between David Bohm and Krishnamurti, where the reader witnesses epiphanies happening in real time. He released a whole series of transcriptual writings where he spoke with scientists, theorists and spiritualists discussing time and existence. It’s an exploration into the space where something new is being created. Sunna and I had long talks about the role of arts within the political sphere through that lens of being-in-creation, a speculative fiction/reality which can only happen in media res, its process coming into the world…

S: … and the show turned into a series of works which are glancing in to the unknown. I see each artist contributing richly to this as some works are in the midst of a decomposing process while others are proposing alternative, heterotopian and even utopian future scenarios. It opens up many discursive trajectories into means of poetically looking forward to what agency artists have today. The term sci-fi never came up in the process, but I saw it turning into a very sculptural, material speculation. We are interested in technology, robotics and ecosystems, but perhaps the role of the arts is to look into the thinking behind it. What the works in the show have in common is this speculative nature that image-making and representation have towards the question of and what then? We are all anxious about it and there is increasing worry and trouble arising in each of us as to how to solve current world problems. I found interesting to look into what contemporary artists could add to that dialog in their own way, without being guided towards making an exhibition strictly about the climate crisis, let’s say. This I feel made a poetic turn within my personal curatorial approach and I felt an increasing sense of trust in the fact that the works would evoke justful contemplations into these themes.

B: Rúna Thorkelsdóttir’s sculpture made of garden cress hangs gently and touches the floor of the gallery. It’s growing and contained at the same time, reflecting our relationship with nature and our longing to control it. The work has a life of its own, stripped from its natural setting and ultimately decomposes during the exhibition period. Can you tell me how our impact on the earth is effecting these artists’ thoughts?

S: Rúna’s work in particular makes the process of life and death visible. You can see the roots on the backside of the piece. The exhibition has only been going on for a week, and runs for six weeks! The cress will develop according to their circumstances, which are not ideal in this case. They’re supposed to be dying, but as with organic substances, it decomposes rather than rots. There is an element of chance here which allows things to take their natural course.

B: Uncertainty is in the air, for sure. Our times are dominated by instabilities and ambiguities, as is visible in f.ex. Huginn Þór Arason’s work. His sculptures from 2002 display plastic containers with colorful play-doh sculpted around them, perhaps hiding the reality of plastic waste with ornamental and colorful gestures?

S: Huginn’s work came from the archive of the Living Art Museum and I saw it bring the discourse around the conservation of an art work. The sculptures were much fresher when first made. When unboxing them, the crafted clay had turned soggy, crumbling and collapsing on top of their supports. It’s interesting to place together these different processes, between the natural and plastic, man made material. In both of these cases, we can wonder how time treats art works, and how we experience works from the past today if they are intentionally or non-intentionally supposed to change over time?

B: Would you say it’s a bit like unfreezing something?

S: In a way! As someone from the cultural sector you find yourself constantly dealing with this maintenance in art works such as these. You unfreeze them, blow the dust off and constantly check if something needs repairing. Often the works need re-adjusting or re-making the work all together! However, for Huginn’s piece it became necessary to show them as they came out of the box, as a slightly altered version of the works that were made a few years ago. With both of these artists, I see them creating a space for the viewer to contemplate this change in relation to their own body.

Thorvaldur Thorsteinsson’s video is another great example. His Most real death (2000) shows people taking turns staging their own death in front of a camera when shot at by a finger-gun. It exhibits this type of anticipation we live with, this knowledge we all have. In a very bodily way, you are confronted with your own reaction of the work. You might laugh at the first three enactments during this simple game of pretending, but then the violence kicks in. It’s a total of 37 people staging their death in front of the camera. I feel this work describes very well the overall approach that the artists took to the show’s themes. There is a lot of color and humour before the terror reveals itself to you. The viewer realizes that experiencing art changes over time, just like the artworks are evolving, decomposing and taking new shapes as the exhibition continues.

R: I feel it’s also interesting to look at the impact of humour that Thorvaldur’s work has. It’s meant to questions our ethics, but through this very specific style that he shares with his generation. It has this slap-stick like quality and a visual poetry. It reminds me a bit of Bas Jan Ader and how he staged emotions like sorrow or grievance. This particular body humour and gestural action had a lot to do with these artists. It is a very different type of humour if you compare it to the younger artists in the show. I feel that contemporary artists are faced with a totally different type of anticipation. Maybe one which places the body in relation to its environment, or attempts at contemplating, in a physical manner what is to become of this relationship. The younger generations seems to have a much darker or dystopic view of things.

S: Definitely. I see your work, Rebecca, along with Steinunn Gunnlaugsdóttir’s and Andreas Brunners as contributing to another conceptual thread of the show. I think that artists today are faced with the contemporary worries brought about by the human’s imprint on nature and other people. We seem to be haunted by guilt, on top of our anxieties, and we perform these socio- and political acts of undoing what we’ve done wrong. Perhaps even to see at what point in these complex relationships we actually belong?

B: Here we can transition from the utopian to the more contemporary idea of gender and the body, which I see resonating in Rebecca’s works. Would you like to tell me about the somatic onesie?

R: I just have this small anecdote before we go into that. I have a good friend in Berlin, who is 25, and getting her PhD in astrophysics. She is working with potential future environments for planets, and other complexities beyond my comprehension. One day, I mentioned that I was envious of her generation, as everything seems to be so possible in terms of creating new living conditions, gender fluidity, open communities. She turned to me and said bluntly: “but you will die a natural death, and our generation will witness the earth die first”. She is busy exploring the nuts and bolts of how to survive the earth’s destruction and what consequences it has for its inhabitants. When she said this, I was just like “woah…” She is in the science world and she’s confronted with these really real problems. The time is running out and figuring out an alternative before the 2050 deadline is just a very high, practical priority for her and the contemporary science world.

S: And here the anxiety kicks in again…

R: For sure! I had just never, thought that far!

B: Is the youngest generations of art students and scholars more inclusive because of this hidden knowledge? Is it because we are running out of time and they realize that it’s best to just join forces?

R: It’s something we can’t understand. In the past, there were generations that went through wars and saw the potential end of the world. But those were all very hypothetical, man made conclusions. We found ways to continue because we still had enough resources to re-build what we destroyed. Now the problem is actually real. The sciences today are actually trying to understand how to slow down this process or find an alternative in a new ecosystem. I found this extremely interesting.

My work, as in the Somatic Transit Onesie, romanticises evolution. I made it in 2015 for a show about the EU in Lichtenstein. It was presented with a sound piece called Stop belonging now. At that time I was idealizing if we could evolve in to a male/female/land-animal/sea-animal type of body. A hybrid of some sort, but seeing this body as already belonging to a past. The onesie piece therefore exists and is presented like a skin someone has already shed. So what comes after is unknown, and does not need to be visually represented. It aims to create a jumping off point for the imagination, I’m always looking for a state of potential; where a work creates an open ended process that is inclusive to the viewers experience. The onesie is perhaps the last point of materialization, what comes next is open.

S: This work is also about removing external markers through this dialog with the viewer. We have so many borders, there has always been this connection between the “one” and the “other”.

R: Stop belonging now, the sound piece, creates the notion of ending belonging in order to belong everywhere. Without perspective, point of view, in order to perceive all viewpoints. Erasure as a way of empowerment. As soon as you come to one end of the spectrum you’ve gone full circle. Identifying in the middle is where you get stuck. Fixed positioning is just a very strange and dangerous concept to me! Conservatives, who have fixed opinions about the LGBQT communities and then these same communities have fixed ideas about how a conservative thinks… our societal standards are always to reject a notion, or fight against a norm, the position is always fixed against something. I’m looking for a non-binary positioning which is neither on the offense nor defence. A place which is neither/and/or. A non-binary positioning which can’t be polarized.

B: Would you say this is totally neutral ground? What does this new life-form present itself as?

R: I don’t really believe in sameness, I believe in fluidity, process, and continual flux. But it’s just the level of which one zooms in or out. We talked a lot about non-being, about consciousness, about wholeness. There are many theoretical discourses about parts of a whole, but why do we constantly speak about parts? We’re always dissecting, categorizing, and picking at things on such a zoomed in level. It somehow takes away from just being in my view, takes away from the interconnectedness.

S: The print that Rebecca presents in the exhibition is a work in progress that might take on another form or become a part of a larger series in the future. I’m pleased to include this work in the show, as it strongly suggests a new kind of animal/human ambiguity and questions notions of intimacy and our preconceived notions of gender or our place in the natural world. On the side that faces the window we see a human holding this dog, but we can’t really see its a dog. You can sense that it’s an animal, by our reading of creatures. There is a beautiful collision that happens.

R: It was a great process working with Sunna. She understood the works before they entered the exhibition because she had this overview of what it could become. I was very happy to hand the choosing to her and where the print ended up being in the space.

S: Each artist added to the discourse of the exhibition, and its ideology was shaped through the unfolding of dialogs and experiencing the works themselves. It became important to me to keep the dialog open towards the end. This photowork is just, really, sensual and materialistic, it fell in to place after having strong dialogs throughout the entire process.

B: So, in the beginning the concept of the show was very open, and it’s theme’s come more through working with the artists?

S: I had specific questions that were related to the landscape of exhibitions happening in Iceland when I started working on the show. I knew it was going to have a socio-political angle to it. The framework shaped itself through having discussions and actually seeing what each artist contributes instead of forcing them in to a specific curatorial agenda.

R: Our first conversations were about doing a political show. But you were not really interested in overtly tackling contemporary politics, as in, protest, or propaganda let’s say…

S: It is about what we perceive as political art today and what role art can play in the political landscape. If you place something in the world, it always says something and that’s what we wanted to bring attention to. The works reflect on and invite you to re-think our current situations, deal with your anxieties, engage. Not in a didactic way, they propose what political positioning artists may be taking and have an inclusive positioning towards the viewers own time and place.

R: I think it’s overtly political to be against something. That is the easiest positioning, to be against something or with something. As a contrast to this show we can recall an infamous moment that Nýló had in 2011 with Koddu. It was a politically charged exhibition. Much of that work was radically against something. This was important at the time of course, as we were facing financial crisis. Right now, however, I think that political art should be about engagement and discourse; finding ways to form connections, even just being intimate.

S: The presences of the works in this show are strong. They can be evocative, questioning and disturbingly confronting. The atmosphere of the show is thought to offer this type of open engagement…

R: … and I really feel like this show escapes all tag line theories, which has a positive impact. It’s liberating to participate in a show that does not associate itself with a specific theoretical model or an -ism.

S: The anthropocene was a topic that came up frequently in my conversations with Andreas Brunner and I think that many people might discover that, while others discover something else in his work. Some people are engaged with choosing -isms and theories attached to exhibitions and I know that the risk of not having such strict tag-lines or themes might result in a chaotic exhibition.

B: I think that with this positioning, the poetry of the exhibition reveals itself. Coming back to Andreas Brunner, it gestures at our attempts to undo the things we have done to nature by covering up our workings and re-workings in to the earth’s layers. He reflects on this through small marble pieces, which is usually thought to be a very sacred material, something which can’t be manipulated. We’re always dealing with these gestures of undoing, as artists, as people.

S: There is almost no untouched surface on the earth left, and at the same time we’re very unapologetic about it, we seem to constantly be in the process of covering up our own traces. It is as if we were idealizing our own absence and idleness at these places, as if nothing ever happened.

R: There’s also a trend now in idealizing native and indigenous traditions, and it’s usually done by white people. I find this trend not only awkward, but also total cultural appropriation. This show, on the other hand, is more about looking forward instead of trying to get back to. I do think we need to unlearn industrialization and recognise our animalistic sides and deeper connections to the earth and all living things: but without trying to emulate the past.

B: There is constant guilt in the air of those who have oppressed and suppressed, for example how the colonisation of Suriname or the Dutch Caribbean in the Netherlands is being undone through the renaming of places or the revisiting of their culture by white people. It does lie on a very sensitive border and has an awkward feel to it. It’s part of the process of becoming guilt-free of the past, of righting wrongs. But honestly, how else to do to it? What comes next?

S: Exactly, why is there this need to become guilt free? We’re in a place where we can’t undo more. We are acting oblivious to what comes next. I had a talk a few days ago and they asked me what if all these terrible things happen and we just survive?

B: You mean, what happens when we actually inhabit a place we can’t imagine what is like at this time?

S: Precisely, what happens beyond this beyond?

B: I think one of the stronger points in this show is to refuse a single categorical umbrella. It brings forth the personal anxieties in each participant and invites more intimate readings as to look into the role of art within all these contemplations. The universal is explored through the personal. There is more space to think about the possibilities than what should be or what we should have done. I find this very important, to localize these problems and share them.

S: We hear about the artist as being a mirror of society, but we seem to have lost what the mirror shows us. So my question becomes, what is the errand of art in society today? There has never been a reflection which shows you the real, so the creation of personal, alternative heterotopias become a way to actually explore this question. Ultimately, the artists here are exploring their role just as it is important for everyone to attempt a private understanding within our current state of things. The reflection is found in the artworks and I have found great readings in each of the works here. As a curator I’m interested in seeing how an artist can make political art without overtly educating and narrating an audiences experience. How to make an artwork which is not with or against, and actually trusts the experience that the work brings about in itself?

R: We’re not here to tell you how it is. We like things to have a life of their own and trust in the life that the art piece can have. Sometimes the artist sets limitations with their intentions by using text or didactic forms. Sometimes we don’t realize it, but at most times an artwork can have a much bigger identity than the one the artist insists on. Using naming, or words, can be a limitation. It’s time to celebrate the situations that an artwork can set up with any crowd without leading them to a certain conclusion or opinion. Many people come up to me and they say “oh you had that guy on the floor! It looked great!”, and instead of being like “well, actually, it is a… and it means this, and you should interpret it exactly as I do”. I just don’t like to be told when to change my position, my reading, my experience.

S: The truth is, logic just follows what you experience, directly. You should always trust the viewer to make their own conclusions, based on their experiences. They should not be controlled, and my intention is making a show which is accessible to people who don’t necessarily visit art galleries on a regular basis. It is important for the arts to participate in any contemporary political discourse we are facing, be it a local or a global one. What is even more important is that the arts should be inclusive and welcome to different readings. We are all facing these problems and I find it interesting to see what the arts can show within the current spectrum. With such a diverse group, who all contributed greatly to this journey of speculations and questions, I wish to create a fertile, poetic ground to contemplate what is to come. This is what I hope translates in to the viewer, who always adds something to the dialog just by experiencing.

Bergur Thomas Anderson

The exhibition …and then what? runs until 4th of August 2019.

Photo credits: Vigfús Birgirsson

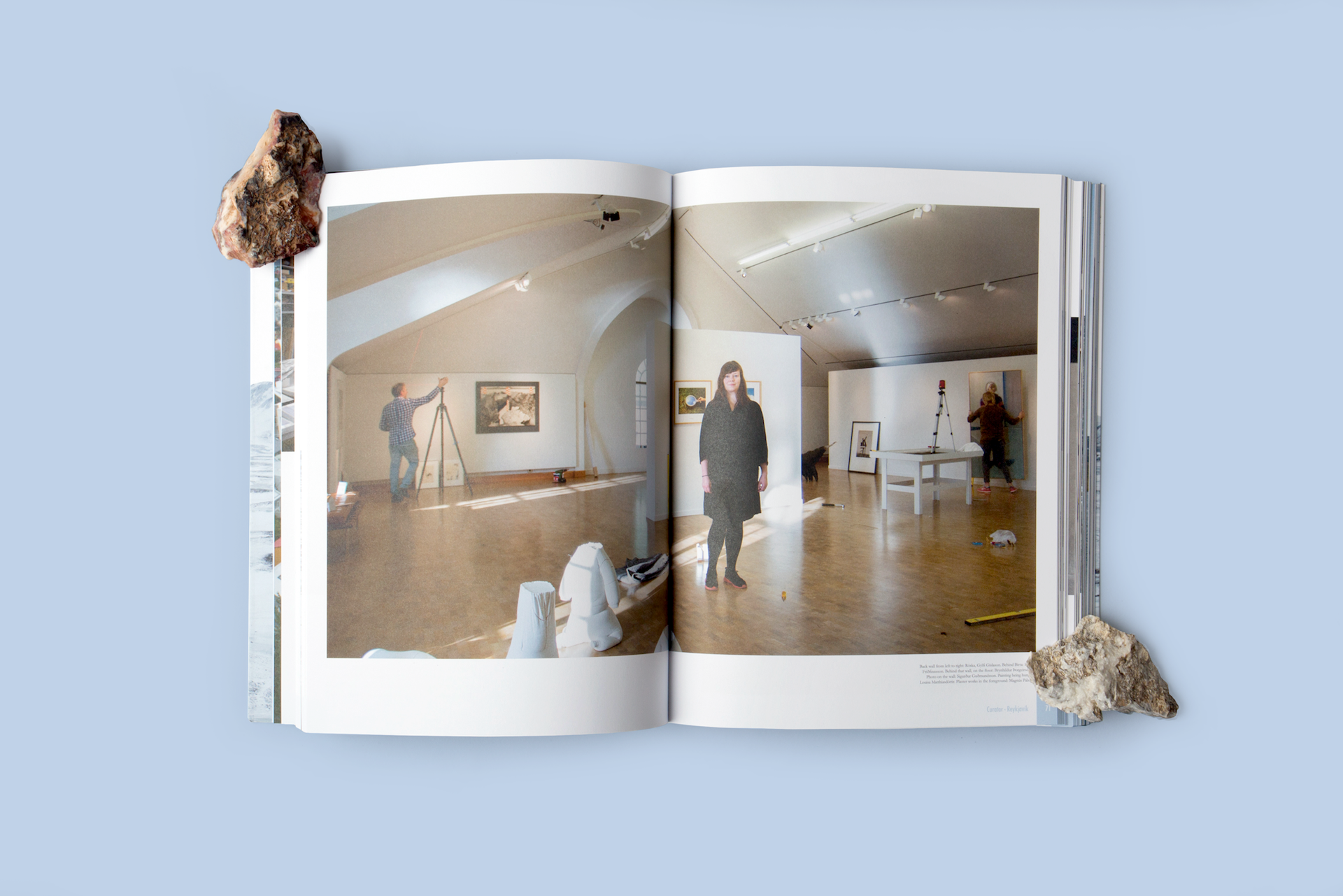

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery. Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery. Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Sigurður Guðmundsson, Eggin í Gleðivík, Djúpivogur, 2009.

Sigurður Guðmundsson, Eggin í Gleðivík, Djúpivogur, 2009.