Black is Light by Claudia Hausfeld and Klara Sofie Ludvigsen

Black is Light by Claudia Hausfeld and Klara Sofie Ludvigsen

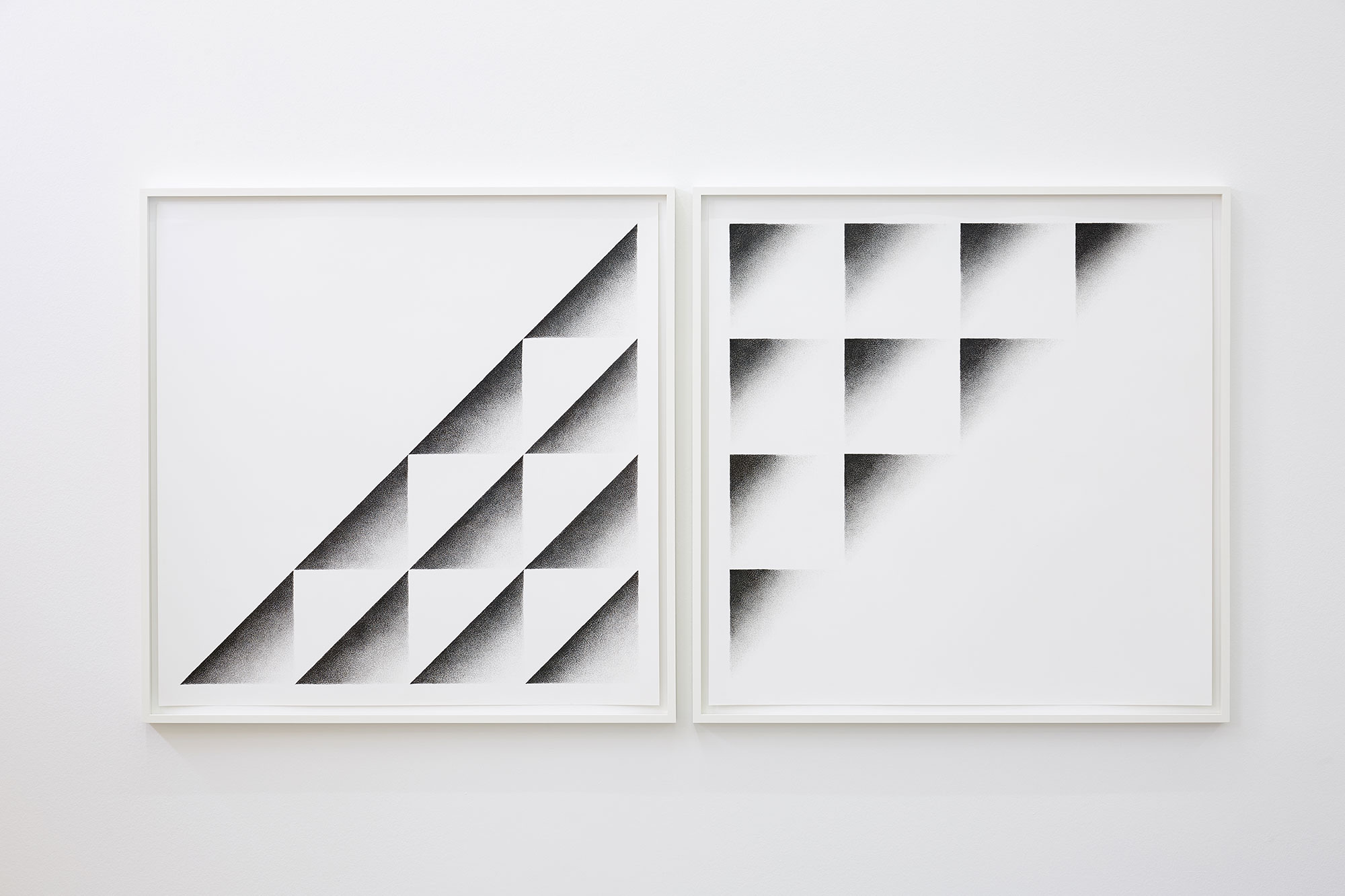

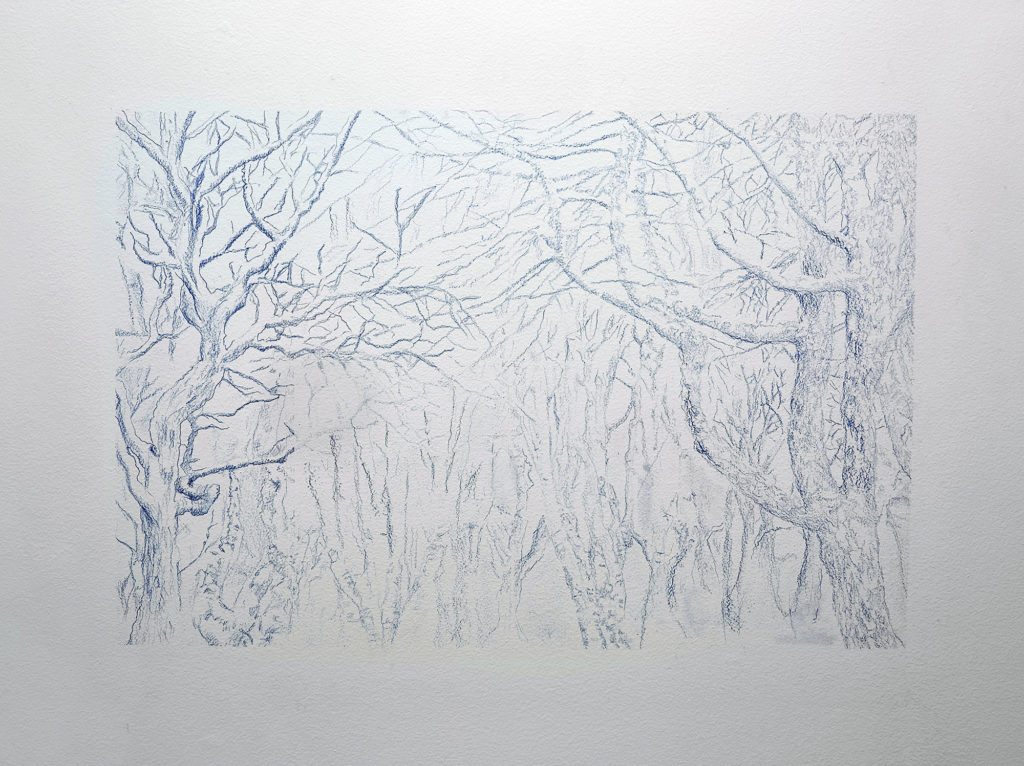

The exhibition, Black is Light, by Claudia Hausfeld and Klara Sofie Ludvigsen is on view at Harbinger until the 24th of June. In the exhibition, black and white analog photographs are not as they appear on their surface. As one scans the surface of the images, the conflicting meeting place between the proof of the image and the imagination of the observer is constantly revealed. Both slight and blatant manipulations made by the artists disrupt the reception of how one usually absorbs a photograph, demanding a sharpening of the gaze. Such is the magic of painting with light in the darkroom, as well as the suspension of working in with darkroom processes which the artists shared with me in the following interview.

Erin: As I was looking around at the works and noticing how well they work together, the question I really wanted to figure out how to answer was: Whose is whose? I think it is because the photographs work so well together. How would you describe a way to differentiate between your works?

Klara Sofie: I think there are many ways of answering that question. One concrete thing is how we work in the darkroom. I work in the layer with the negative whereas Claudia works on the paper so that is a difference but you can’t really see that. It’s just something we know.

Erin: That is the exact kind of information about the work that I think is so interesting to know because it’s something we would never know, or see.

Claudia: I think you can even say that it is all darkroom images, which is a fundamental ingredient in our work, and that it is done in the darkroom and that it is chemicals and light which made the images.

Klara Sofie: It is important as this process is informing the outcome. Claudia is doing it on the paper like stopping the light from working on the surface whereas I am doing it with the negative by taking new negatives on glass or on transparent paper with different techniques. So I’ve always stopped the light when the negative is on a layer.

Claudia: The enlarger we use in the darkroom functions like a reverse camera. The paper we print on is like the negative in a camera, and the negative itself is like the thing you take a picture of. The higher up and further away the negative is from the paper, the larger the image. And by doing it Klara’s way, by putting a drawing or painting on glass together with the negative, you also enlarge the painting on the surface of the image, so you see these lines that were painted on glass or plastic were enlarged along with the image, whereas mine were printed directly on the images so it is not enlarged. It is more of a photogram, like a direct copy.

Erin: That really gives it a totally different sense. When I look around I feel like they have a totally different depth feeling to them.

Claudia: I was wondering about this one for instance. It is really difficult to tell what is image and what is negative.

Klara Sofie: I think it is lead because this is a negative combined with a positive. What you are looking at, the white part, is a positive, which comes out negative, which means it is a black lead lying on the foreground there as salt storage. That is the light blended into the other images which is a negative coming across as a positive.

Claudia: I just don’t understand this image. You know this thing with photography where you know you are dealing with something that was actually there but you just can’t believe it. Did you cut on the negative?

Klara Sofie: No, when I placed them on top of each other this is what came through because the salt is white and when it is a positive that is where the light shows through and it gave room for the negative to show.

Erin: This is the positive and this is the negative?

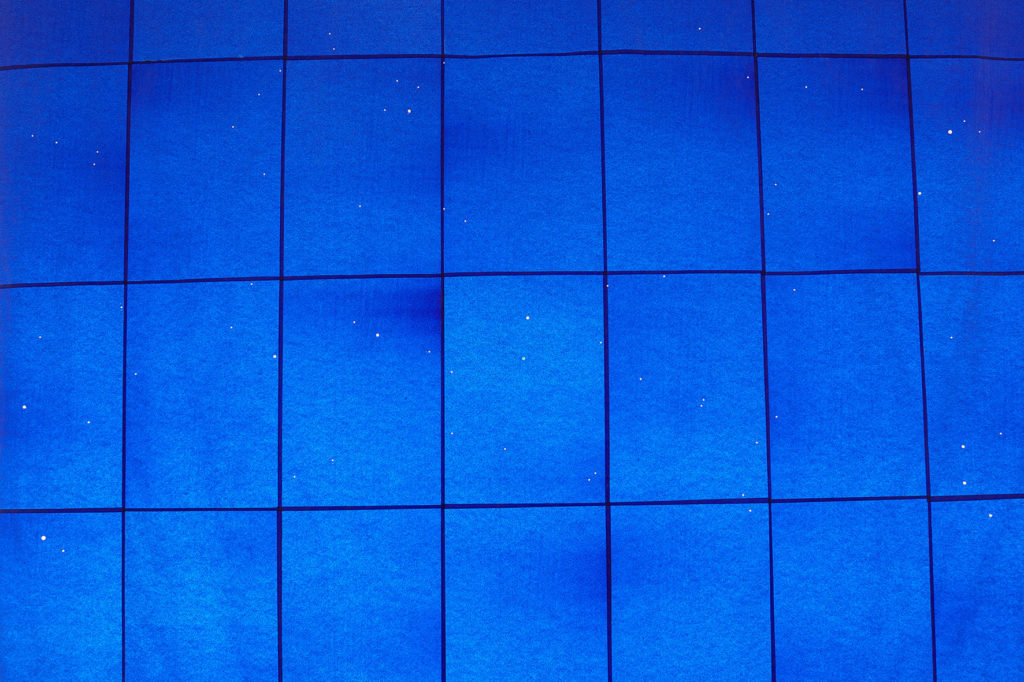

Klara Sofie: No, that is just the opposite. It is very easy to get dizzy when it comes to positives and negatives because part of the process is to constantly turn it which is what the title is playing on as well because what is black in the negative stops the light, and becomes light in the photograph.

Claudia: For this image I made a torch with this little nose out of paper, like a funnel. So the light only came out of this tiny hole. I placed the paper with a red filter so it didn’t expose it and then I switched it on the torch and went all over the place with it, making a drawing.

Erin: So you made black with light?

Claudia: Yes, because that is how the photographic paper is burned; it turns black.

Erin: And this is Claudia’s?

Klara Sofie: No, that is mine. But this is a strange one because it is also painted on glass in the same size as the negative and then doubled so it is a painting and a photograph. This is a special version because it is light leaked on the paper which, in a way, relates them even more to Claudia’s because it is not something I usually do.

Claudia: What I like is that it has this randomness in which you can see how light behaves in these stripes.

Klara Sofie: I don’t understand the logic of it. I don’t know how this appeared because it doesn’t really make sense the way it is placed.

Erin: How does it feel to work with something that you don’t always understand the logic of?

Claudia: It is so exciting; I really love it. I guess I work like this because I do something on the paper itself. The thing is, you are in this room and you can have this red light on so you see quite a bit and you take out this white sheet of paper and you place it there and then you put some light on it and when the light turns off the image is still white. It seems like nothing has happened but you know that latently there is an image on that white sheet of paper. Then you take it and you put it in this tray and magically something appears; this moment is such magic every time.

Erin: It still has so much variation at that stage in the process of creating the image you want.

Claudia: Yes, of course. You can take it out earlier and you can switch on the light and change everything up.

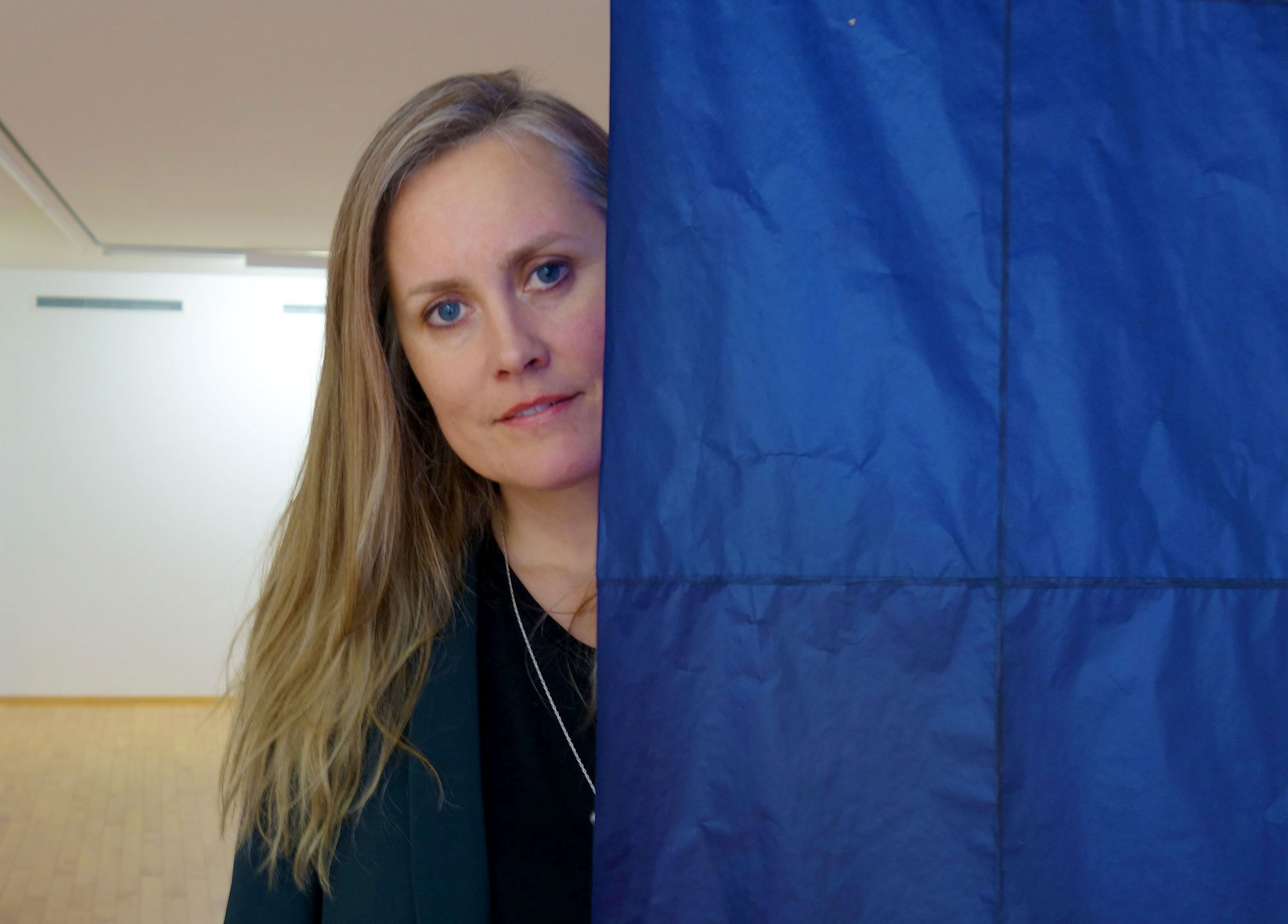

Erin: How did you two meet?

Klara Sofie: We were paired together. We had never met before and we were asked to do a collaboration together. First we had an exhibition in a gallery in Bergen in April 2018. That was the first time our works met and we were pleasantly surprised. It was a very funny experience because we saw that they spoke so well together. We were laughing quite a lot.

Erin: Can you tell me more about this one?

Claudia: It is a little bit of an experiment because I wanted to illustrate the whole darkroom process in an abstract way; painting an image in layers. So I took that idea and decided to make shelves, also inspired by Klara who was making these shelves with glass. This sequence of images I made by walking around a hole and every step taking a picture. I wanted to make the hole three-dimensional to keep true to the process. In the darkroom, I placed this tiny piece of paper in the middle also and crumbled it smaller and smaller until it almost disappears at the bottom-most shelf.

Erin: There is a lot of illustration of the photographic process going on in the exhibition.

Claudia: Of course, because it is very process-based and also very playful. Actually, with none of the works was I preconceiving that I was going to make this kind of image or that one. I browse through my negatives until I find something that I’d like to play with.

Klara Sofie: For me, for years I found photography to be quite a stiff medium. It’s very formal because it has so many processes that make it feel very controlled, unlike painting, which is more improvised. I am working to make it more improvisational and playful because I wanted to have more fun, so eventually I just had to give up control. So, this way of working is just a result of this release of control and matching what I’m painting with different negatives and seeing what compositions appear and sometimes it clicks and sometimes it doesn’t but it does after a while. It’s just a constant process.

Erin: Photography does carry with it this heritage of stiffness.

Claudia: It is actually a theory that I would like to explore a little bit further. I’ve been looking for literature about this digital/analog dichotomy. Photography released painting because, after the inception of photography, paintings didn’t have to concern themselves anymore with the representation of reality and it could sort of fall back on itself and research itself. This was always the thing that photography had to deal with: representation and depiction of what was there. Now it is digital photography that has taken that in all forms like scanners and surveillance cameras. Now that everything is digital photography, analog photography can finally concern itself with itself. It doesn’t need to represent anything anymore. The need to show that ‘this is what existed’ is gone. It feels kind of fresh and free because now it is really painting with light.

Erin: It is being returned to its core, so to speak.

Claudia: It is so funny because it isn’t a painting. It isn’t a pure invention of my hand and brain. It is still real stuff but I can tweak it and play with it.

Erin: The way you are both manipulating the photographs in the darkroom process really disrupts the observer’s ability to ‘scan’ the image. It’s like you are dismantling the whole linear process of one thing leading to another and creating your own world within the photographs – breaking the spell of the photograph. Any final words?

Claudia: I would like to add that it is such a nice feeling knowing that people can work together, yet separately, on a collaboration. We just played on our own and it came together. Now, when I’m working in the darkroom I love knowing there is someone else out there doing the same.

Erin: Thank you Claudia and Sofie.

Erin Honeycut

The exhibition was on view from June 2nd to June 24th as part of a collaboration between Tag Team Studios in Bergen, Norway and Harbinger Project Space in the context of the B-Open Project ‘Norden TIL Bergen.’

Photo Credit:

Featured image: Erin Honeycut. Exhibition photos: Claudia Hausfeld.

Artists websites:

Claudia: claudiahausfeld.com / Klara Sofie: klarasofie.com