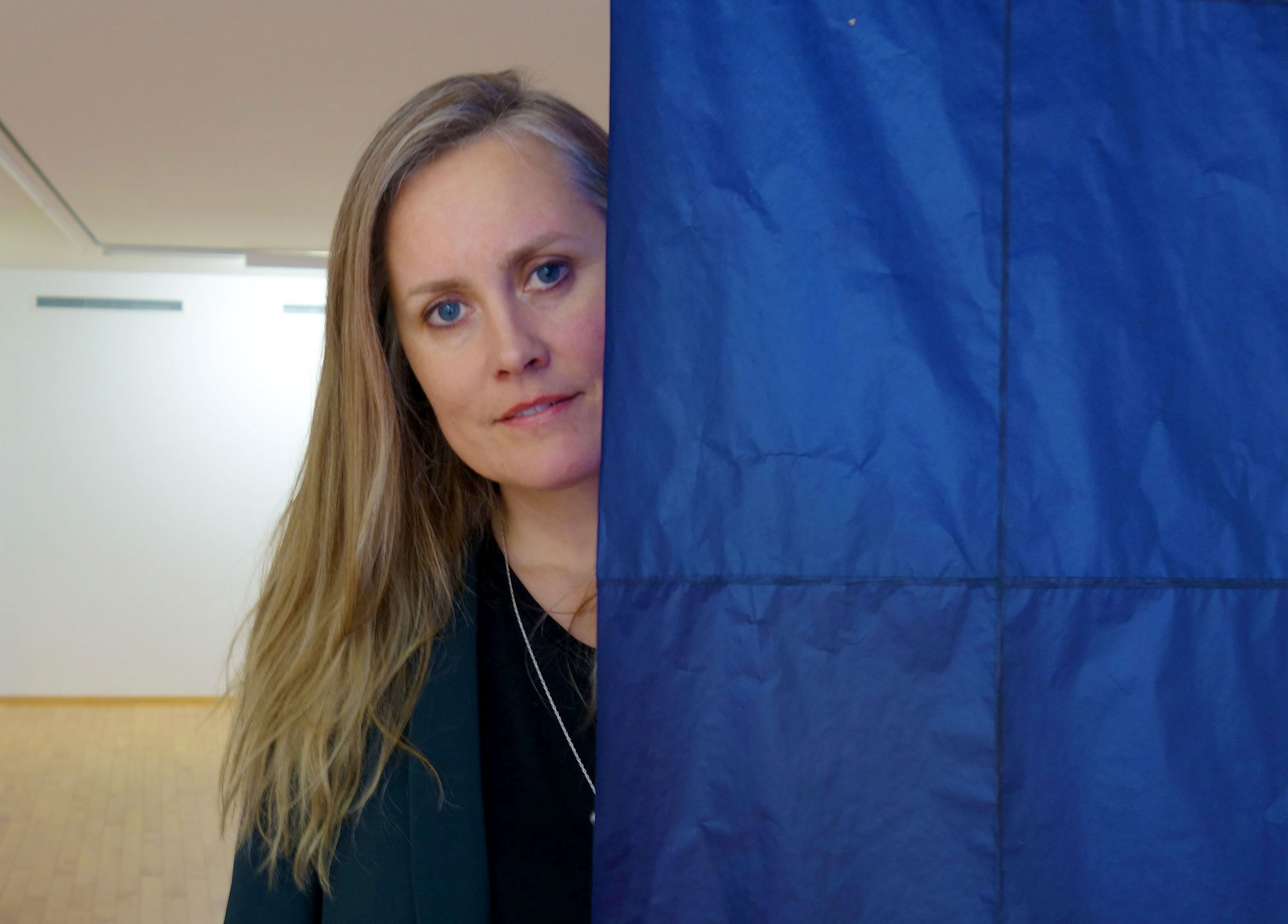

Anna Julia’s Serenade

Erindi / Serenade is on exhibit at Hafnarborg Centre of Culture and Fine Art until October 22nd. In the exhibition by Anna Júlía Friðbjörnsdóttir, various elements are taken from sociology, astronomy, poetry, and ecology, into an acknowledgment of the biggest crisis´ currently facing the world. Like a natural scientist who uses poetry to interpret her findings, Anna Júlía looks at ways of addressing climate change and human migration that recognizes human vision. In the following interview, Anna Júlía and I discuss the exhibition and her concern with the synthesization of meaning- from the 19th-century Romantic movement to biometric identity management systems.

Erin: The first perception of the exhibition for me was the impression of there being many layers involved: the art-song lieder tradition, the Romantic notions, the migration of the Passerine species to Iceland, references to human migration and the weather. Can you tell me more about how all of these are related?

Anna Júlía: The starting point was the birds. I had seen in the news years ago these announcements about Vagrant birds arriving in Iceland. It was in 2005 that I first started paying attention to it and I always wanted to look further into the different species. I came across the Singers, as they are called in Icelandic, and found them interesting not least because they are predominantly a European and Asian species associated with the Old World that migrate from Africa and other southern destinations. Then I looked at their distribution patterns and it struck me because it looked like maps of human migration into Europe. I had been thinking a lot of Europe, and how we, as a whole, are tackling the challenges of migration today.

So I decided to narrow this down to the Old World Warblers because of this pattern and how they come to Iceland in particular. I thought there was a correlation between the birds and the influences and culture that originate from this Eastern direction that Western societies are based on but we think we are independent of it somehow. I thought it was an interesting way to look at one species and look into smaller examples of our ecosystem and how it’s changing – a macro view. It just represents a much bigger picture of something that is in flux and seems to be happening very fast. So there are social and political issues that factor into my interest in this, but on the other hand, there is also the climate change issue and you can’t really separate the two. Of course, that is only part of the story about how all these things are related.

The other thing I should say regarding the birds is that it is not just the changing of these fundamental systems, but also the systems of taxonomy we created in the 18th century- these man-made systems that we have stuck to and maybe are just now realizing are fixed choices that aren´t necessarily truths that we have to hold onto. The Warbler species are very old, dating back around 16 million years. Linnaeus classified many of them and some were described in his 1758 Systema Naturae but in recent years these birds have been the source of much taxonomic confusion and rearrangements within the taxonomy. This is because of new technologies and genetic research. This case is like a little snapshot of this kind of changing worldview.

Erin: It reminds me of something I was just reading in preparation for our discussion from the Finnish cultural theorist, Jussi Parikka, who writes about how recent technological networks are modeled from systems in ecology and especially migration patterns, herds, and swarms. I saw a connection between his ideas and some of the points you were touching on in your exhibition.

Anna Júlía: It also shows us how nature is much more complex than we tend to realize and that these very complex patterns are there and that we can look into for inspiration. I like Parikka´s comment: „It’s the environment which is smart and teaches the artificial system.“ Although I am looking at natural patterns they are not necessarily the super-developed kind such as swarms but the accidental as well.

Erin: Yes, I think it’s this anthropocentric point of view of nature that has simplified things, but that is not the case.

Anna Júlía: It brings into question where the human comes into it, the co-creative factor of the human as narrator.

Erin: In some ways, the Romantic Movement in art, literature, and music really was inclusive to this connection between humans and the environment on all levels. Do you think there is a clue to how we handle the huge upheaval of human migration and climate change in the arts, and specifically how we see connections between the humanities and the natural sciences? Do you think this movement can give us a clue as to how to navigate all these changes?

Anna Júlía: I think definitely there is a connection. The Romantics were also coming out of a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, so that is maybe what is parallel with today- these similar issues in a different context. In my work, of course, I am using it as a metaphor. In relation to the exhibition, the Romantic sentiment is a total contrast to the scientific and the kind of systems used in science. I brought in these Romantic lieder songs as a contrast to the scientific thought. The songs also give the exhibition a narrative which would otherwise have been an installation consisting of a few parts. I broke it up into pieces and attached each one to a romantic song and in that way, gave it some narrative. Also, the poems bring in a human voice and in that relation, the Romanticism speaks of this need for freedom- a basic human need.

And in the context of the work, the poems put them in context with the night as the spatial and temporal dimensions of human experience. The poets were allowing themselves to focus on feelings rather than the hard-core rhetoric of Rationalism. I think that is also what we need now and I think there is a demand for emotional intelligence.

Erin: Your exhibition also holds an allusion to the era when Europeans were creating categorizations for the natural world and putting it into systems for our analysis- maybe this goes back to what we talked about earlier in trying to find clues to our current situation by creating a new model of thinking about nature and culture, human and non-human? As much as rationalism has carried Western civilization forward, it also needs to be paired with equal doses of empathy and understanding, which was obviously the Romantic reaction this period’s mechanical focus.

I think you capture that really well.

Anna Júlía: That’s definitely what I had in mind- a call out for more empathy. This rationalization, of course, applies to the human classification going on now. I found similarities between the taxonomic classification and the human cataloging, especially in the problem that Europe is trying to address. We have created these laws in the last century when the UN was formed- human rights laws and laws pertaining to refugees. We need to adhere to the basic beautiful idea of the laws but they are being stretched, borders have moved away from the actual physical borders not in a way of inclusion but exclusion. Once a person trying to enter illegally is caught, he or she is registered and cataloged almost like a taxon in a way that people in the western world would never agree with being treated. These databases are very inhuman.

Erin: What about some of the more material aspects of the exhibition – can you comment on this continuing theme of fragility and ephemerally in the materials being used?

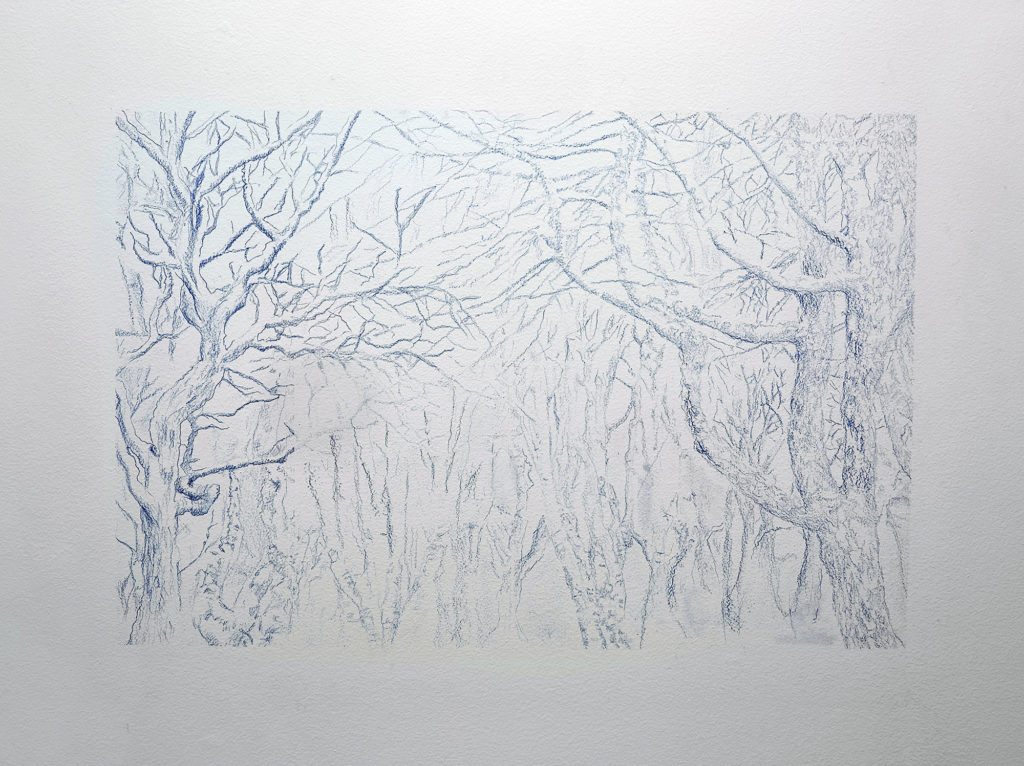

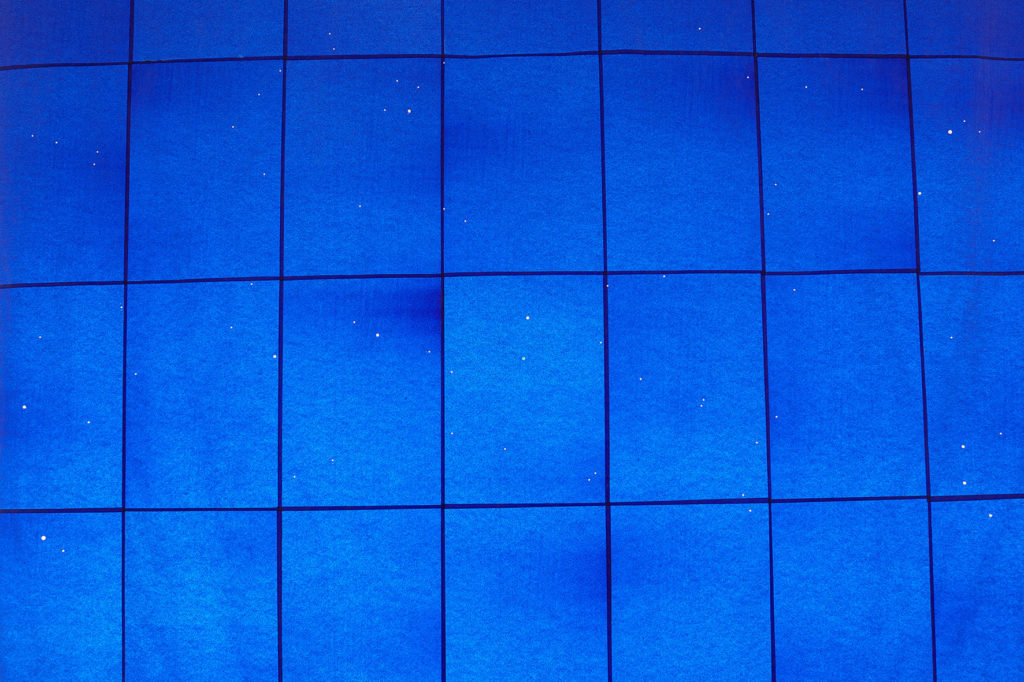

Anna Júlía: Yes, the choice of materials is deliberate, of course. The xenon gas and the fragile paper reflect the ephemeral nature of the subject matter as well and how these ideas are a bit afloat. Because we were talking about the wind and birds being carried by the Eastern wind, I wanted to choose materials that were reflecting this ephemerality. I am interested in primary elements and in the transformation of elements be it in technology or nature. I chose these as basics- the carbon and xenon. Of course, I’m playing with the etymology of the words as well. Xenon comes from the Greek word for stranger and carbon is a word that is somehow intrinsic to the discussion of climate change. But then the carbon paper is itself a material of fragility and lightness and also holds this possibility within it because it’s indeed a tool, something to make a copy with. So these are the material factors but to me it represents bureaucracy. I used the carbon paper as well to make the drawing of trees at the far wall opposite of the window.

Erin: Can you tell me more about this drawing, Mondacht / Moonlit Night?

Anna Júlía: The tree in the drawing represents the home for the birds because they live in trees and are insect eaters – but it can also be a home or a shelter generally. But again, it’s also part of the language of the Romantic night, dark and the North, trees, and forests being part of that. Then again it’s just a copy, so there is a kind of dreamy feeling about it. Maybe it’s just a kind of faint memory or a vision. The title and the location within the space also have significance in relation to ´reading´ of the works.

As I mentioned earlier the lieder songs lend the exhibition a narrative. It has a beginning and an end and you can read the exhibition in this order with Ständchen / Serenade being the first piece. I don´t see the work being illustrations of the poems but they get an added context and a certain tone. You could say that each piece is twofold – the physical, straight work and the emotional connotation of each poem, which is almost, like a sub-theme. For instance, Ständchen / Serenade is a positive, light song and has this inviting or luring factor at the same time as setting a melancholic tone.

My songs beckon softly

through the night to you;

below in the quiet grove,

Come to me, beloved!

The rustle of slender leaf tips

whispers in the moonlight;

Do not fear the evil spying

of the betrayer, my dear.

Do you hear the nightingales call?

Ah, they beckon to you,

With the sweet sound of their singing

they beckon to you for me.

They understand the heart’s longing,

know the pain of love,

They calm each tender heart

with their silver tones.

Let them also stir within your breast,

beloved, hear me!

Trembling I wait for you,

Come, please me!

(Ständchen / Serenade, D. 957, Schubert, 1828, poem by Ludwig Rellstab)

En Dröm / A Dream, by Grieg, also has something positive and hopeful about it. The piece, two adjacent barometers, has to do with the measurement of the world which isn´t accurate and juxtaposes two very different things – a scientific measuring tool and the idea of the dream, which is the only connection to the poem.

Then, To Evening / Illalle, which is the carbon paper sheet with the star constellation mapped into it, is the point when you enter the night with its dreams and sense of refuge.

Come gentle evening, come in starlit splendour,

your fragrant hair so soft and darkly gleaming!

Oh, let me feel it round my forehead streaming!

Let me be wrapped in silence, warm and tender!

Across your bridge of magic, smooth and slender,

my soul would travel towards a land of dreaming,

no longer burdened, sad, or heavy seeming,

the cares of life I’d willingly surrender!

The light itself whose bonds you daily sever,

would flee, exhausted, seeking out those places

where your soft hand all toil and strain erases.

And, weary of life’s clamour and endeavour,

I, too, have greatly yearned for your embraces.

Oh, quiet evening, let me rest forever!

(Illalle / To Evening, Op. 17, Sibelius, 1898, poem by Aukusti Valdemar Forsman)

Mondnacht / Moonlit Night is such a beautiful poem and the song a perfect calm. I get the feeling it pauses time, you´re kind of poised in the quiet moonlit night.

It was as if the heavens

Had silently kissed the earth,

So that in a shower of blossoms

She must only dream of him.

The breeze wafted through the fields,

The ears of corn waved gently,

The forests rustled faintly,

So sparkling clear was the night.

And my soul stretched

its wings out far,

Flew through the hushed lands,

as if it were flying home.

(Mondnacht / Moonlit Night, Op. 39, Schumann, 1840, poem by Joseph Eichendorff)

And the last piece, Après un rêve / After the Dream, which is the bird skins in the vitrine with the Xenon light above. The poem has a tiny glimmer of hope that is never realized. One is brought back to reality again and it’s the end of the dream. We don’t know if the birds are sleeping, or in a coma, or dead.

Drowsing spellbound with the vision of you

I dreamt of happiness, burning mirage,

Your eyes were gentler, your voice was pure and sonorous

You shone like the dawn-lit sky

You called me and I left the earth

To flee with you toward the light

For us the heavens opened up their clouds

To reveal unknown splendour, glimpses of divine light…

Alas, alas, sad awakening from these dreams

I call out to you, oh night, give me back your lies

Come back, come back, radiant one

Come back mysterious night.

(Après un rêve, Gabriel Fauré, 1878, lyrics by Romain Bussine)

Erin: What about this use of carbon blue which flows through each piece and the inversion of the natural colors to these ultramarine hues in the bird portraits in Ständchen / Serenade?

Anna Júlía: It came about for a few reasons. Aesthetically, I just thought it was very interesting how the feathers almost look like they’ve been inked in, but it’s also a way to distance myself from the scientific approach, as a filter to get away from that. But then it also has something to do with the night because they are all spotted and photographed in the daytime. It is a reversal both of the colors and the original daylight photo could be a night scene. So there were practical and conceptual reasons and it all came together in this fusion. I just like the colors. It was also a bit of a chance finding because the reversed images have the same blue tone as the carbon paper. The blue drawing on the wall is just made directly from the carbon paper.

Erin: Haven’t you made allusions before to how colors were brought to Europe from the East, in your exhibition at Harbinger last year, for example?

Anna Júlía: Yes, I had previously used the symbolism and history of colors. In the exhibition you are referring to it was Tyrian-purple that originated from Phoenicia and was a symbol of wealth. In Serenade the color is ultramarine blue. The name comes from the Latin ultramarinus, literally „beyond the sea“ because it was imported from Asia by sea. It was imported to Europe from Afghanistan in 14th and 15th centuries.

We connote it to the Far East as well, to China. There is also something about it in that it is not a color in Icelandic nature that you can find naturally. Blue was always a very exotic color in Iceland because you could not get it naturally from nature so it became a sign of someone with wealth who had been traveling abroad. At the same time, blue is also our national flag color so there are many associations. Xenon is also blue when charged through electricity. Also with Xenon being used in searchlights, it is enlightening, in a way, bringing something to light. Yes, so the blue color is there for many reasons but not least because of references to ink and bureaucracy.

Erin: There is also a thread of navigation in the exhibition, of the notion of finding ones’ way in the dark or through difficulties.

Anna Júlía: The theme of finding ones’ way is important especially with the star map and the way the birds navigate. It’s not just those finding their way to a better life, but also us as Europeans, and every human really, in navigating the best way to face these challenges.

Erin: There are so many endless correlations in the exhibition that it really becomes a constellation of sorts. Everything is connected on some level of meaning to everything else, micro and macro – the transformation of centuries of thought as well as the lifespan of a single bird.

artzine would like to thank Anna Júlía for the interview.

Erin Honeycutt

Installation photos: Vigfús Birgisson. Portrett: Helga Óskarsdóttir

For more information about Anna Júlía’s work, visit her website: www.annajuliaf.com

Playlist:

https://open.spotify.com/user/1189549579/playlist/7szowWHtdm3DRXUUWb0D8x