Erling Klingenberg í Marshallhúsinu

Erling Klingenberg í Marshallhúsinu

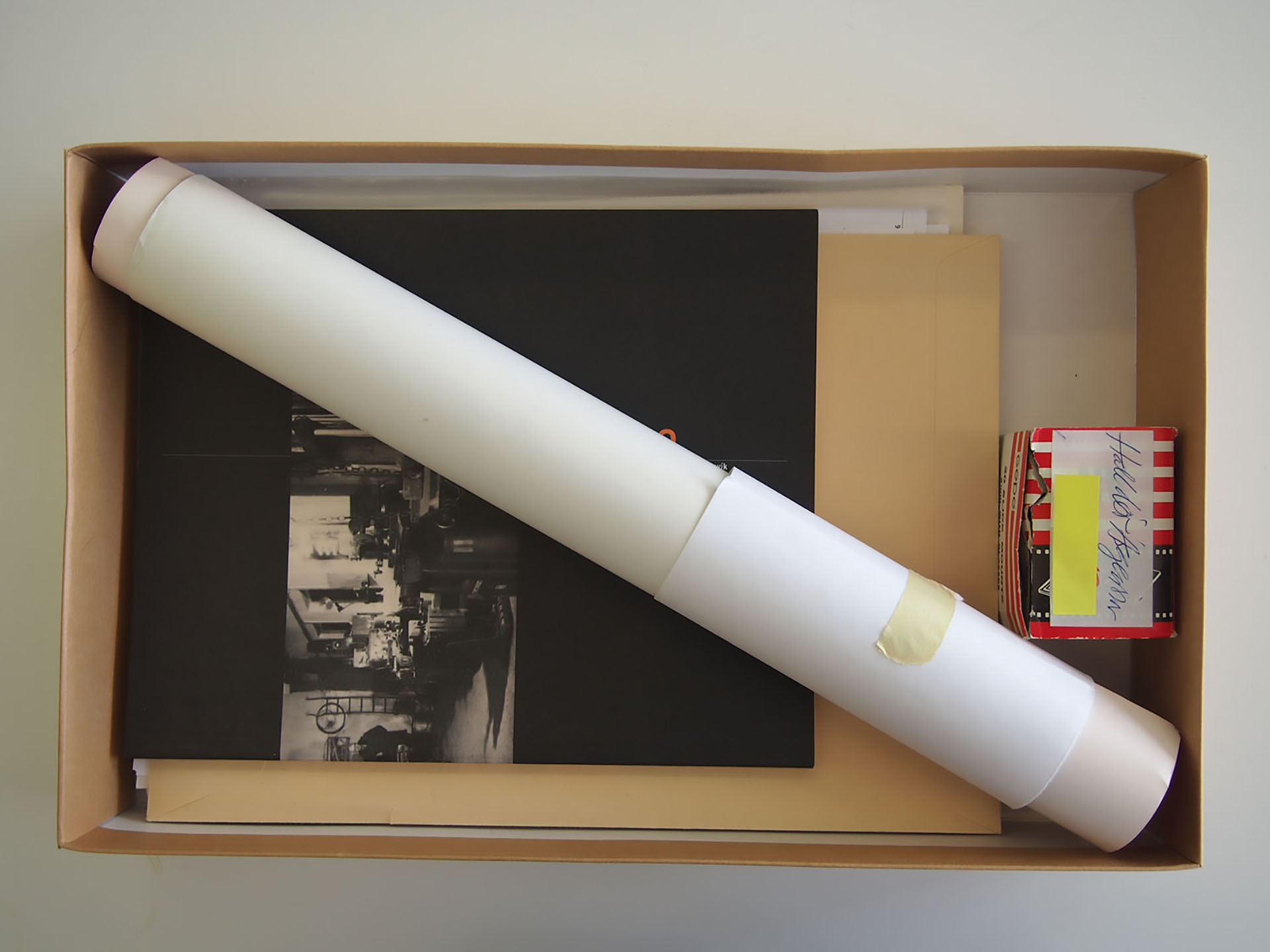

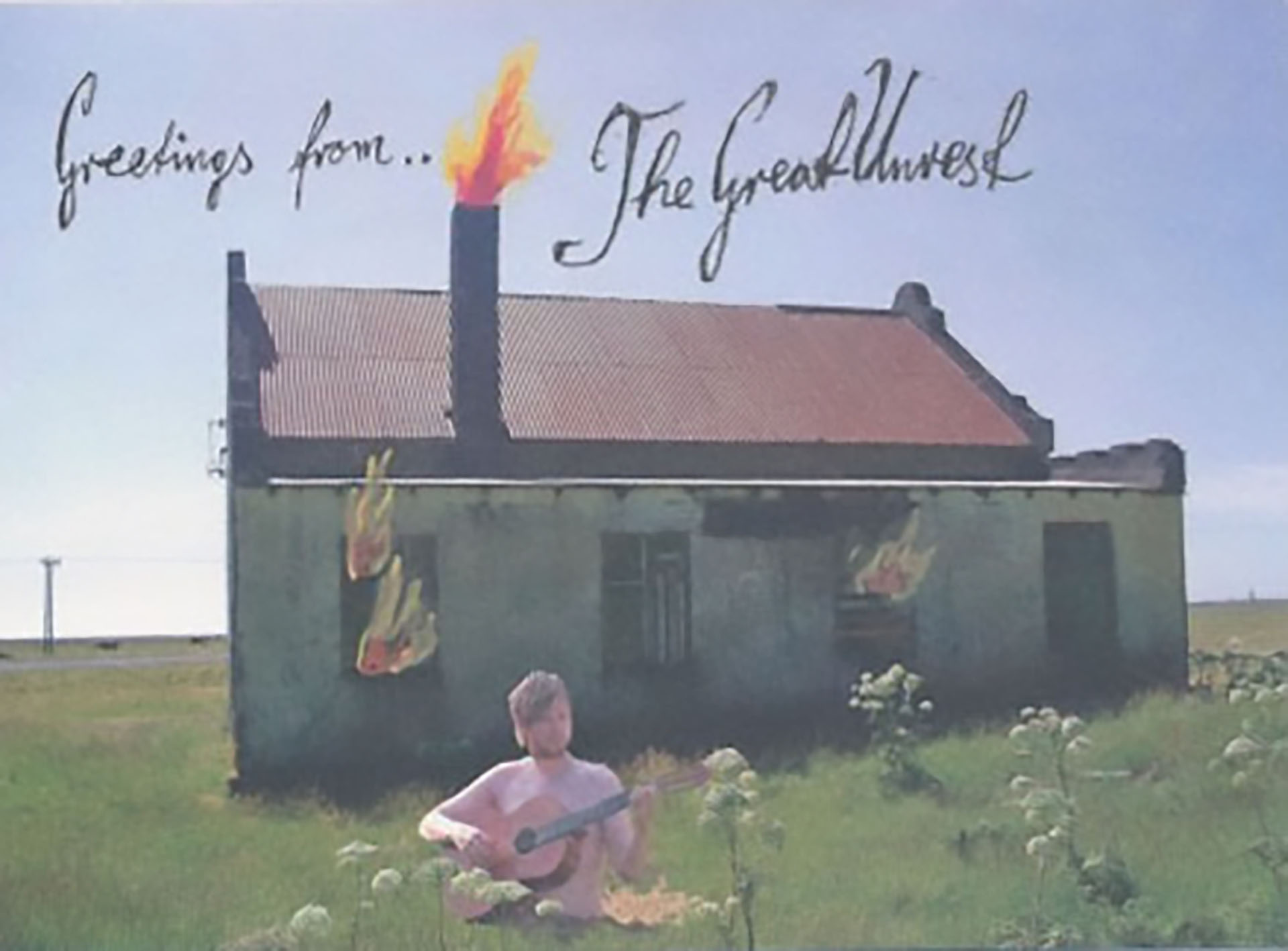

Yfirlitssýningin Erling T.V. Klingenberg er nú til sýnis í Marshallhúsinu. Hún inniheldur verk frá síðastliðnum 25 árum af ferli Erlings. Erling er einn stofnandi gallerísins Kling & Bang sem nú er í Marshallhúsinu og hefur verið virkur þátttakandi í listasenunni á Íslandi sem og erlendis í þau ár sem tímabil sýningarinnar gefur til kynna.

Í verkum sínum og á hinum mismunandi tímabilum sem sýningin spannar tekst Erling á við hin ýmsu þemu. Eitt af þemum sýningarinnar er sjálfskoðun þess að vera listamaður og samhengi listamannsins. Í því þema birtast mér ýmsar skírskotanir til sálgreiningar og karlmennskunnar í hreinni mynd, út frá sjálfi Erlings.

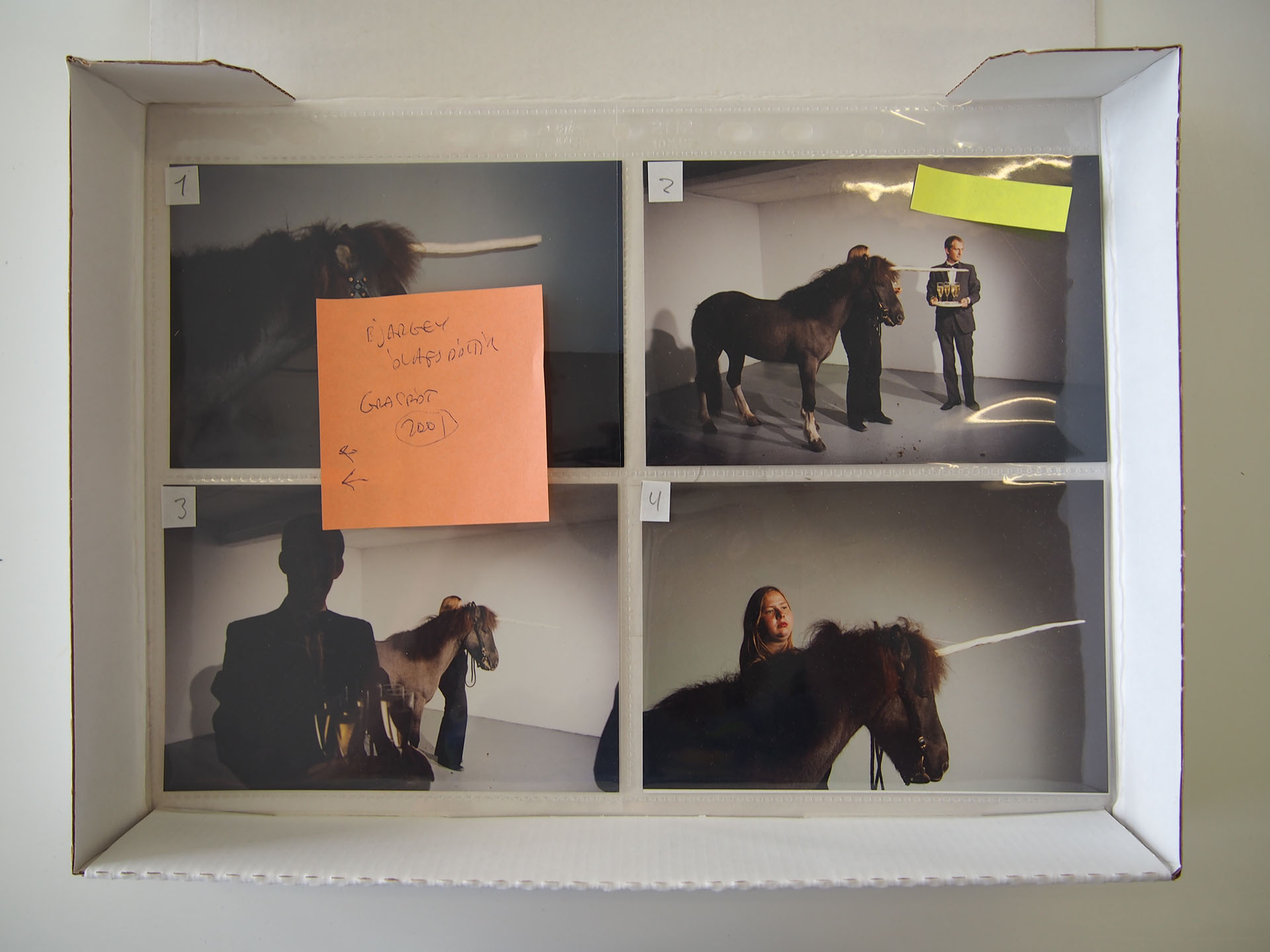

Í mörgum verkunum, ef ekki öllum, tekst Erling á við sjálfsskoðun í gegnum húmor, einlægni og kaldhæðni. Kaldhæðnin spilar sterkan sess í einlægri sjálfshæðni sem virkar vel og er fyndin í verkunum. Til að mynda er það sterkt í verkum Erlings að bendla sjálfan sig við aðra listamenn, bræða sér jafnvel saman við þá eins og sjá má í verkinu á myndinni hér að ofan. Í því er Erling búinn að steypa/blanda andlitu sínu saman við andlit annarra listamanna og fólks innan listasenunar sem hann lítur upp til. Þar af leiðandi kemst hann nær þeim, máir út skilin á milli sín og þeirra – verður þau. Sjálfsmyndin er þannig þanin út fyrir hann sjálfan og er það auðvitað drepfyndið.

Í sama rými er Erling búin að setja upp borð með munum eftir ýmsa fræga listamenn. Rannsókn á myndlistarmönnum. Einskonar safngripum sem hann hefur gripið með sér og safnað að sér í gegnum tíðina, þar eru hlutir sem listamenn hafa snert eða átt, til dæmis vínglas sem Jeff Koons drakk úr og sokkur sem Ragnar Kjartanson átti einhvern tímann. Yfir því tróna myndir af Erlingi sjálfum og lítið rautt skilti stafar Erling Klingenberg. Bendlunin er algjör. „Sjáðu hvað ég hef hitt marga fræga listamenn og það gerir mig milliliðalaust meira frægan sjálfur,“ virðist verkið segja. Á meðan er staðsett til hliðar við borðið myndband af fólki sem allt segir nafn hans „Erling Klingenberg“ og má líta á sem einskonar tilraun til að staðfesta tengingu hlutana við hann sjálfan í undirmeðvitundinni. Það er ekki hægt að skoða hlutina án þess að hugsa um Erling Klingenberg enda myndi það ganga gegn tilgangi verksins.

Útþennsla sjálfsmyndarinnarinnar og afmörkun hennar birtist því sem þema í báðum verkunum, hver er ég án tenginar eða samanburðar við aðra? Virðist listmaðurinn spyrja. Hver er listamaðurinn án samhengis? Og er mögulegt að skapa þetta samhengi sjálfur? Í gegnum eitthvað eins ómerkilegt og sokk? Án þess samanburðar sem er eða virðist oft vera órjúfanlegur hluti túlkunar á list?

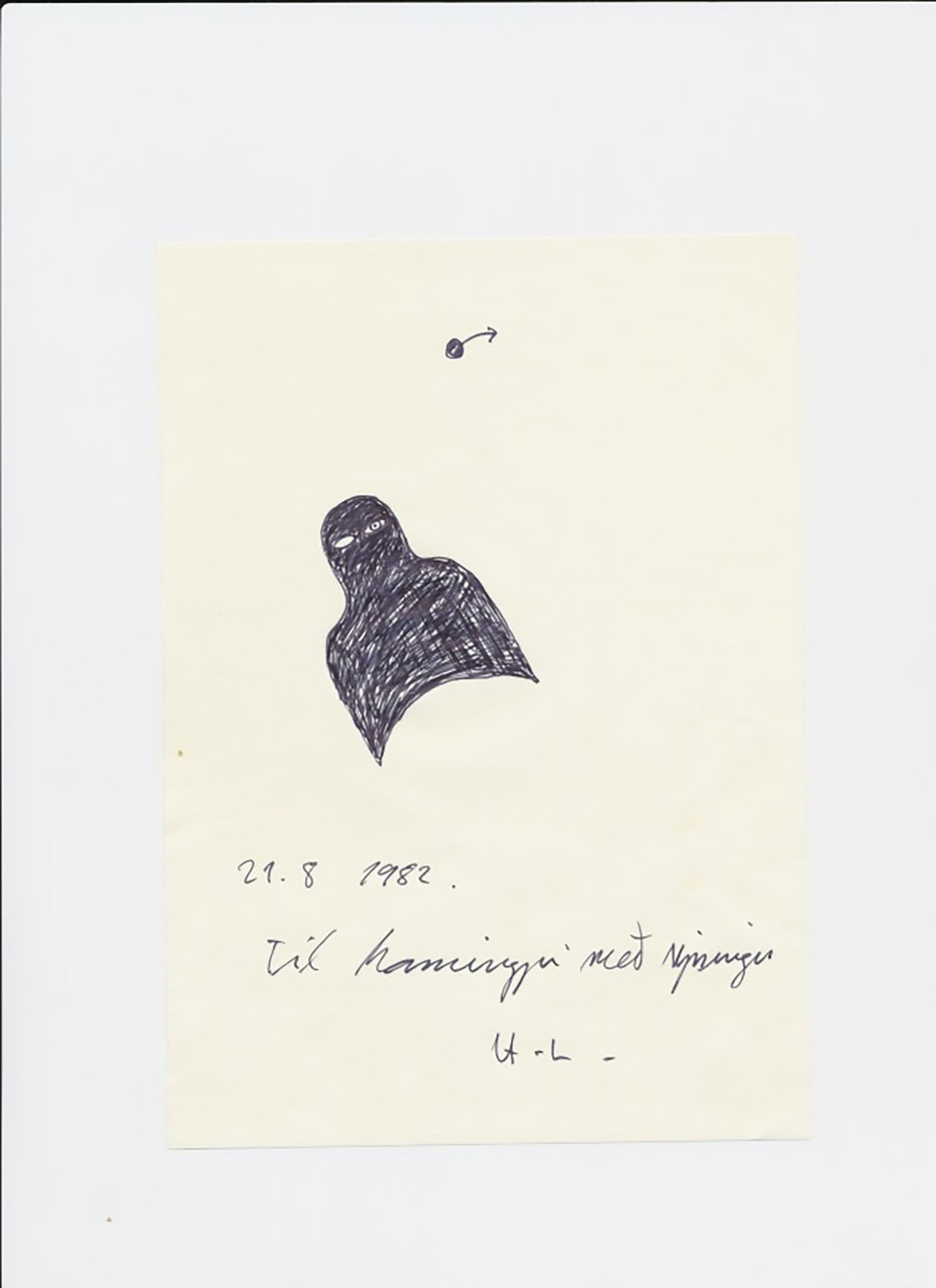

Andstætt þessu verki hanga andlitsgrímur af honum sjálfum sem upphaflega þjónuðu þeim tilgangi að vera fyrir sýningargesti til þess að þau gætu orðið hann sjálfur. Eins konar speglun á sér stað í verkunum, hann speglar sig og myndar úr sér mót af sjálfum sér. Endurskapar sjálfan úr vaxi, Tvífarinn, og nær þannig að búa til sjálfan sig út fyrir sig sjálfan, skoðaðan frá grímum, afmyndunum af honum sjálfum. Þetta minnir óneitanlega á hugmynd Lacans um The Mirror Stage þar sem sjálfsmyndin tekst á við að vera eitthvað til á öðrum stað í rýminu, innan spegilsins og fer að rýna í þennan dualisma. Hér er ég í líkama mínum og þarna sé ég mig í speglinum. Manneskjan verður tvöföld og áhuginn beinist út fyrir okkur sjálf til að líkamsmyndin okkar verði hluti af sjálfskilningi okkar og skoðun.

Verkin eru pöruð á Nýlistasafninu með rauðum vegg sem inniheldur gylltum ramma með silfurlitum striga sem ber nafnið Föstudagurinn langi. Ómögulegt er að spegla sig í verkinu en það er jafnframt ekki hægt að segja að verkið eigi að vera spegill. Spegillinn getur verið falinn í hverju sem er, en það er ekki hægt að spegla sig í hverju sem er.

Tvíhyggja spegilmyndarinnar á sjálfsmynd og líkama má einnig sjá í It‘s hard to be an Artist in a Rockstar Body þar sem sjálfmynd listamannsins sem listamaður skoðar sjálfan sig út frá líkama sínum sem rokkstjarna. Þar sem þessi tvö element eru rist í sundur og sjálfsmyndin passar ekki endilega við það sem birtist í speglinum sjálfum – Rokkstjarnan sem við þráum öll að einhverju leyti að vera.

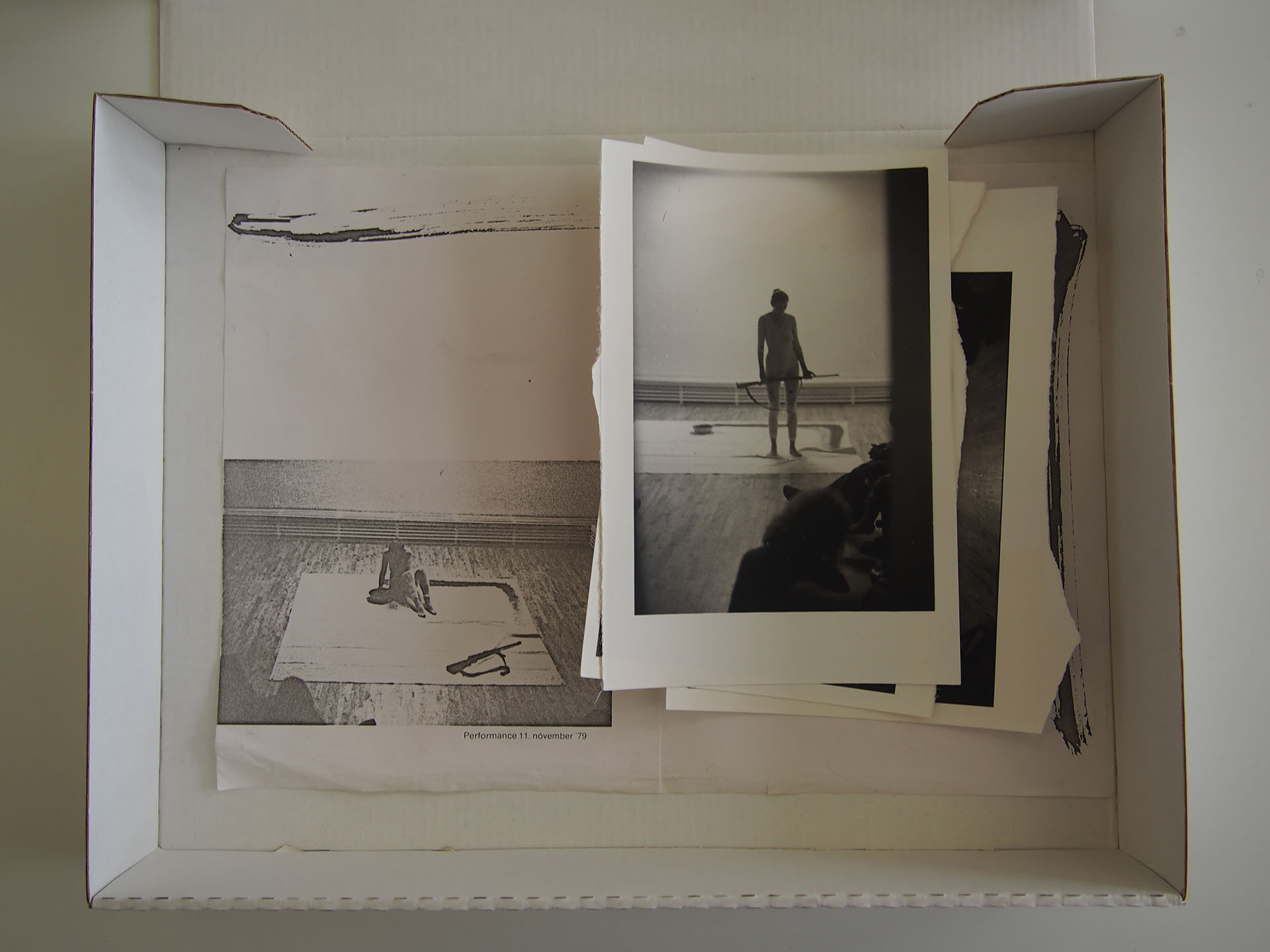

Bendlunin heldur áfram í annarri mynd í Kling & Bang en þar sprettur svipað þema upp í verkinu Ég sýni ekkert í nýju samhengi sem er endurmynd af annarri sýningu, eftir aðra listamenn, sem hefur átt sér stað á öðrum stað í öðru rými. Nú á öðrum tíma í Kling & Bang. Skopstæling uppsetningarinnar felur þannig í sér einhversskonar grín að listinni og listheiminum en einnig honum sjálfum. Hver er frumleikinn? Enginn og þannig á það að vera. Það sem frumlegt er, er ekki til heldur eingöngu þversögn eða tálsýn.

Líkamleikinn fær svo meira pláss í sýningarrými Kling & Bang svo sem, Skúlptúr fyrir skapahár, Kóngur, Grafið og Skapa-sköpum, hafa það sameiginlegt að vera alveg gríðarlega fallísk. Áhorfandi setur sig inn í hugarheim og sköpunarverk Erlings Klingenbergs og heim hans sem karlmaður og hann ræðir sínar fallísku upplifanir opinskátt með öðrum karlmönnum. Karlmennskan nær þannig ákveðinni hæð í sýningunni sem getur verið stuðandi. Yfirtaka á rýminu er hluti af því karlmannlega, því hugvitslega (sýningarskráin) og innan listsköpunarinnar sjálfrar. Á hinn boginn má sjá hana frá því sjónarhorni að hún er opið boð til þess að skoða hin fallíska sköpunarheim Erlings Klingenbergs. Því hann er jú með fallus og er mótaður af sinni upplifun sem karlmaður í umhverfi sem er oftar en ekki mjög karlmiðað.

Eina tilraunin sem gerð er til að breiða yfir þetta fallíska sjónarhorn má finna í inngangi sýningarskránnar sem skrifaður er af Dorothee Kirch þar sem hún segir: „Ég er ekki hrifin af sjarmerandi karlkyns listamanninum […] þessum sem virðast greiða yfir ýmislegt með yfirþyrmandi narsissískum persónuleika og áorka hluti með því að vera mjög sjarmerandi og mjög karlkyns og alltof of oft mjög óviðkunnalegir. … Þá er Erling það einfaldlega ekki.“ Inngangurinn er til að mynda eini texti sýningarskránnar sem skrifaður er af konu en samanstendur af ellefu textum eftir menn sem hafa misjafnar tengingar við listamanninn. Þrátt fyrir að Erling sé viðkunnalegur, að sögn Dorothee, þá segir það ekki allt sem segja má um þetta fullkomna pulsupartý sem sýningarskráin er (en hefði ekki þurft að vera). Hver og einn áhorfandi/lesandi verður þar af leiðandi að dæma fyrir sig hvað þeim finnst um sýninguna sjálfa, sjálfskoðun listamannsins og karlmennskuna sem birtist í henni, óháð því hvernig persónuleiki Erlings sé.

Á köflum er sýningarskráin alvarleg, tekur sér alvarlega, mögulega of alvarlega. Þó eru textarnir marvíslegir (eins og verkin) og stundum er hún er full af sjálfsháði, nákvæmlega eins og sýningin er sjálf. Sýningin er einlæg háði sínu á karlmennskunni. Nær ákveðnum tón af kaldhæðni í garð þessarar sömu karlmennsku sem virkar og er fyndin. Húmorinn er greinilega það sem Erling beitir í sköpun sinni og finna má í yfirbragði sýningarinnar sjálfrar. Það nægir þó ekki að fela sig bakvið húmor og kaldhæðni. En sýningin gerir það ekki og gerir það samt á sama tíma – hún er tvíhliða. Tekur sér stöðu beggja vegna kaldhæðni og alvara. Sýningin er einlæg í karlmennskunni jafnvel það einlæg í henni að hún er berskjölduð og þolir því umræðu um þessa sömu karlmennsku sem í henni birtist.

Tvinna má saman þau tvö þemu sem ég hef rætt hingað til og leyft þeim að tala saman. Í heildina er sýningin samtal um sjálfsímynd, útþennslu sjálfmyndarinnar, spegilsins og sjálf Erlings Klingenbergs sem listamanns í ákveðnu menningarrými og tímabili. Karlmennska er því óneitanlegur hluti af þessari sjálfsmynd og veru hans í listheiminum. Hún getur virkað sem spegill listamannsins við hið víðara samhengi sem samfélagið okkar býr og þrífst í.

Eva Lín Vilhjálmsdóttir

Photo credits: Vigfús Birgisson

Courtesy of Hafnarborg.

Courtesy of Hafnarborg. Gerðarstundin (e. ‘Gerður’s Workshop’). Courtesy of Gerðarsafn.

Gerðarstundin (e. ‘Gerður’s Workshop’). Courtesy of Gerðarsafn. Courtesy of Hafnarborg.

Courtesy of Hafnarborg.