Veröld út af fyrir sig – Samfélag skynjandi vera í Hafnarborg

Veröld út af fyrir sig – Samfélag skynjandi vera í Hafnarborg

Sýningin Samfélag skynjandi vera í Hafnarborg leikur sér með hinn breiða heim skynjunarinnar og mismunandi blæbrigði samfélagsins. Undir yfirskriftinni að hvetja til róttækrar samkenndar (e. radical empathy) sem og að gefa ósögðum sögum rödd býður sýningin upp á veröld upplifana út af fyrir sig. Sýningastýrð af Wiolu Ujazdowska og Hubert Gromny, er hún ellefta haustsýning Hafnarborgar, en haustsýningarnar gefa nýjum sýningarstjórum kost á að sýningastýra.

Alls taka tuttugu listamenn þátt í sýningunni og hún nær yfir öll rými Hafnarborgar. Hópnum tilheyra þau Agata Mickiewicz, Agnieszka Sosnowska, Andrea Ágústa Aðalsteinsdóttir, Angela Rawlings, Anna Wojtyńska, Dans Afríka Iceland, Freyja Eilíf, Gígja Jónsdóttir, Hildur Ása Henrýsdóttir, Hubert Gromny, Kathy Clark, Katrín Inga Jónsdóttir Hjördísardóttir, Melanie Ubaldo, Michelle Sáenz Burrola, Nermine El Ansari, Pétur Magnússon, Rúnar Örn Jóhönnu Marinósson, Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson, Ufuoma Overo-Tarimo og Wiola Ujazdowska.

Sýningin er fjölþætt og yfirgripsmikil; sem endurspeglast í metnaðargfullum og víðfeðmum markmiðum hennar. Eitt slíkt markmið er að hvetja til endurhugsunar sýningargesta gagnvart heiminum, vandamálum nútímans sem og sambandi okkar við náttúruna. Markmiðinu er fylgt eftir með ríkri áherslu á skynjunina en öll verk sýningarinnar endurspegla hvað listamennirnir túlka sem skynjun og hvað það sé að vera skynjandi vera. Í rýminu er stigið út fyrir ramma tungumálsins og sýningargestir eru hvattir: „hlustið með fótunum“.

Er ég gekk í gegnum sýninguna fann ég að verkin ein og sér mynduðu litla króka og kima sjálfstæðra sagna eða skilaboða. Jafnharðan og ég hafði áttað mig á einu verki var mér kippt út úr því með öðrum skilaboðum. Við fyrstu sýn virtust verkin ótengd vegna þess að rauður þráður sem batt þau saman var ekki bersýnilega til staðar. Það rann þó upp fyrir mér að það væri birtingarmynd hins eiginlega samfélags sýningarinnar. Samfélagið sem hér birtist er ekki einsleitt, stílhreint né velur það sér hvaða málefni er mikilvægast, heldur er það margbreytilegt, fjölskrúðugt og getur haldið fjölda málefna á lofti í senn.

Mörg verk sýningarinnar eru gagnvirk og leggja ríka áherslu á þátttöku: listamennirnir bjóða upp á verkefni, að stíga inn í hugarheim og dvelja þar um stund. Gígja Jónsdóttir safnar tárum í Tárabrunn, Anna Wojtyńska og Wiola Ujazdowska gefa plöntur í verki sínu Við þörfnumst öll sólar, Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson og Agata Mickiewicz bjóða gestum í hugleiðslu í verkinu Upphafið í eimingarflösku og Nermine El Ansari teiknar á landamæri í Exercise. Gagnvirknin dró mig aftur og aftur að sýningunni; þú sem sýningargestur ert skynjandi vera og þú tekur virkan þátt í að móta samfélagið sem á sýningunni birtist.

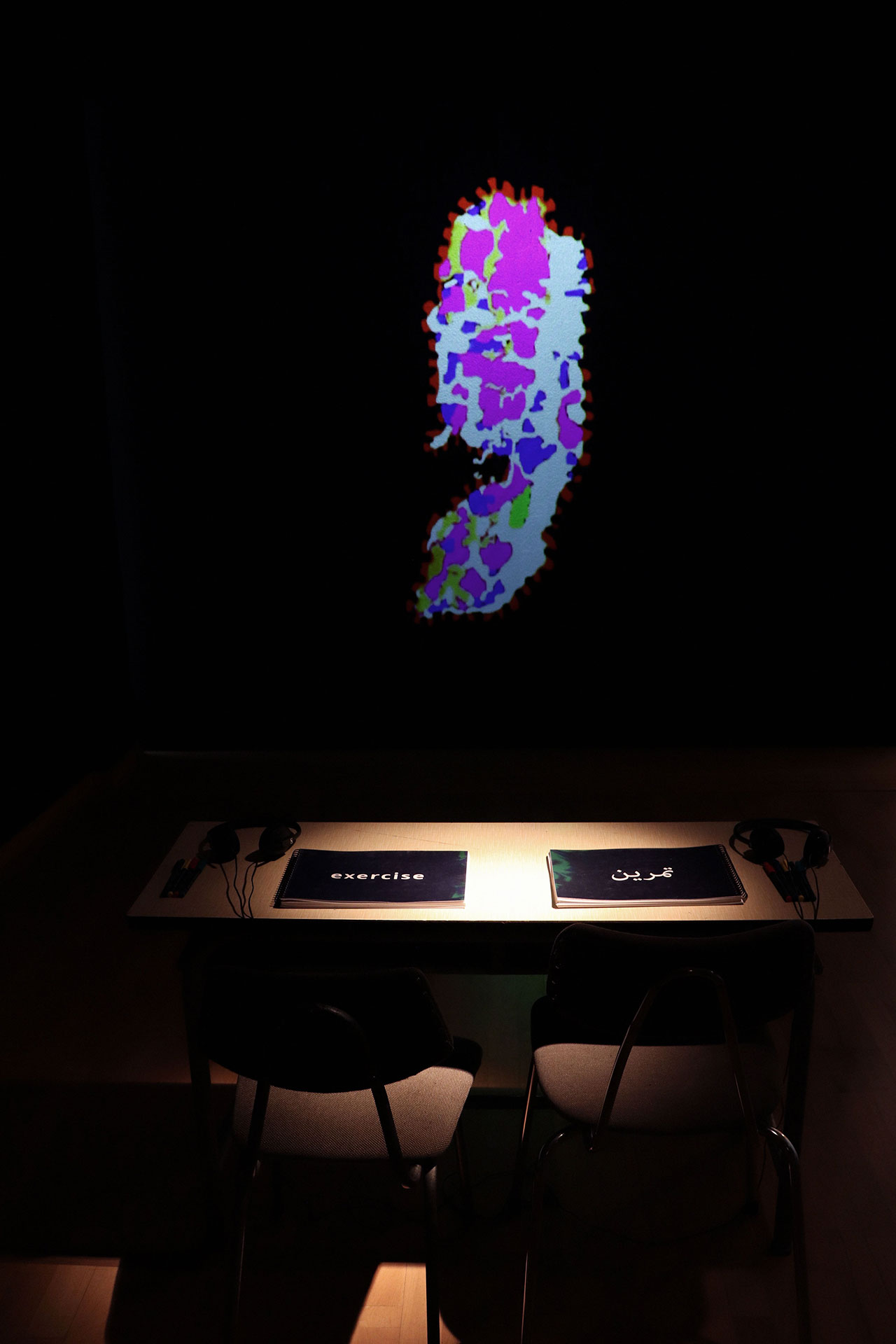

Nermine El Ansari

Nermine El Ansari

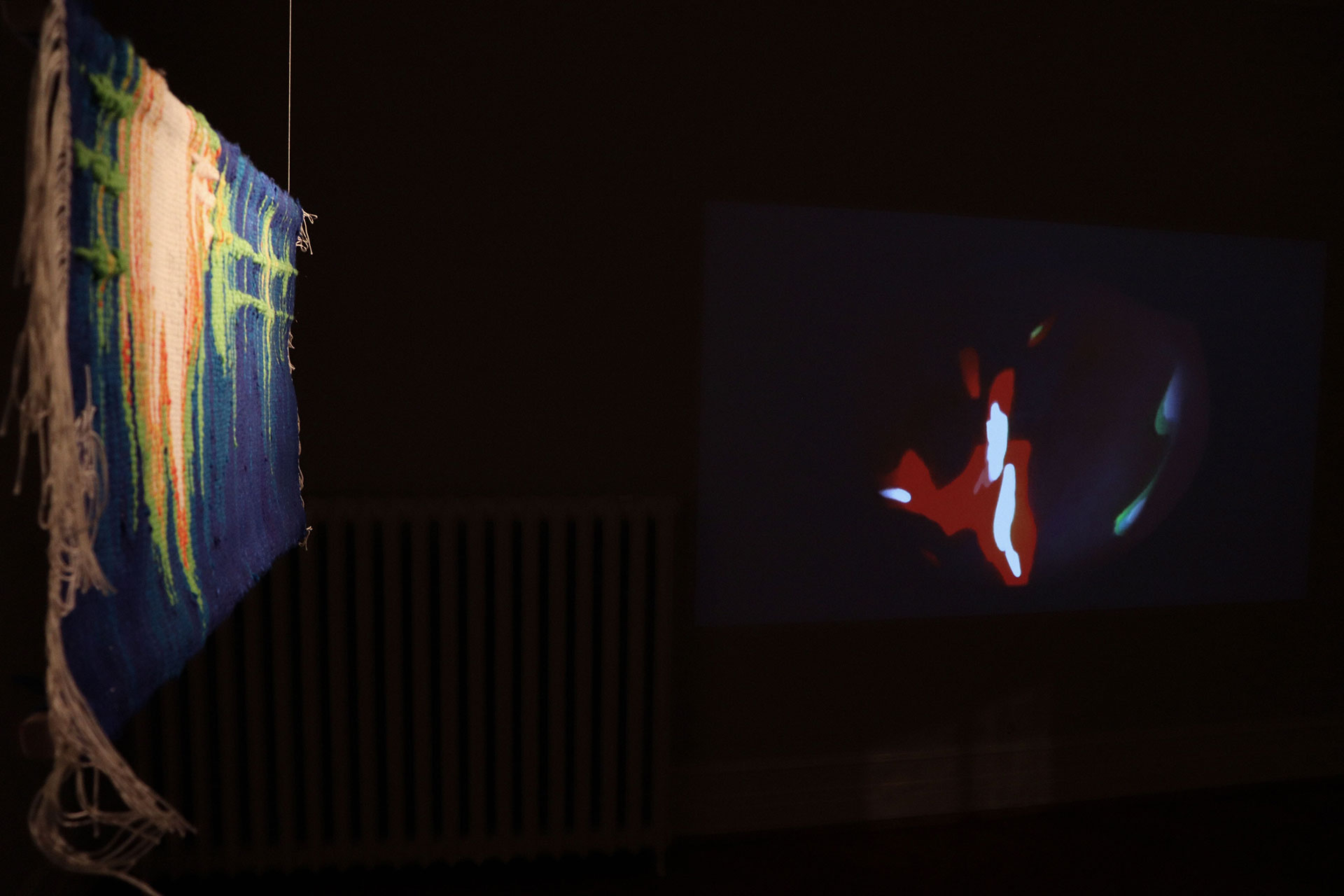

Agata Mickiewicz og Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson

Agata Mickiewicz og Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson

Saman mynda verk sýningarinnar margbrotna mynd af samfélagi sem er flókið og ruglingslegt. Sýningin undirstrikar fremur en að skýra þá upplifun. Að átta sig, fóta sig í nútímanum er erfitt og sýningarstjórarnir leggja gestum ekki lið við að botna eða átta sig á því hvað fer fram að hverju sinni. Sýningartextinn er skrifaður með skapandi hætti og segir lítið sem ekkert sem getur „hjálpað“ sýningargestum við að átta sig á einstaka tengingum milli verka. Mögulega er það viljandi og af ásetningi gert.

Nokkrar paranir verka stóðu upp úr og vöktu athygli mína og umhugsun: fékk mig til þess að lifa mig inn í samfélag skynjandi vera og undirstrikuðu markmið sýningasrtjórana í mínum augum.

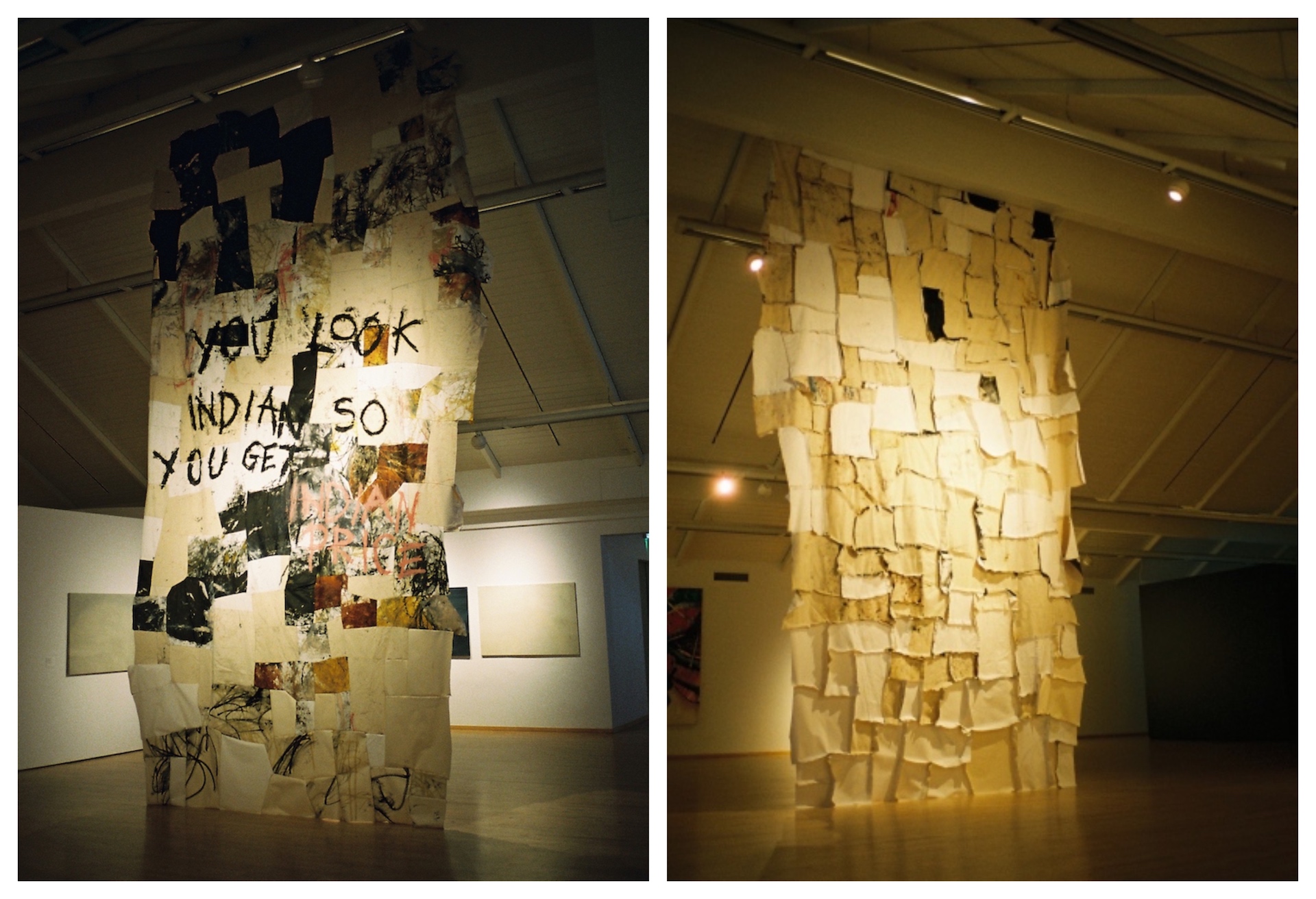

Melanie Ubaldo

Melanie Ubaldo

Pólitískt verk Melanie Ubaldo „Þú ert ekki íslensk. Nafnið þitt er ekki íslenskt.“ talar sínu eigin máli. Skýli reist á sandi, sem minnir á lítið Christo og Jeanne-Claude verk, er umvafið neyðarteppi og gefst gestum kostur á að staldra við inni í skýlinu, finna lyktina af sandinum og dvelja í merkingu verksins. Skýlið er byggt samkvæmt stöðlum Sameinuðu þjóðanna um stærð slíkra neyðarskýla. Þrúgandi veruleiki nútímans er óumflýjanlegur, það er aðkallandi óleystur vandi til staðar. Vandanum er þó velt fyrir sér í fjarlægð frá flóttamönnunum, innan listasafnsins, þannig er viss fjarlægð er til staðar sem minnir á hvernig við horfum á slík mál heiman frá okkur í gegnum netið eða dagblöðin.

Katrín Inga Jónsdóttir Hjördísardóttir

Katrín Inga Jónsdóttir Hjördísardóttir

Verkið er staðsett á efri hæð aðalrýmis Hafnarborgar við hlið annars verks sem kallar á þveröfugt hugarfar. ASMR hvísl og slakandi raftónlist má hlusta á sitjandi á gæru sem breidd er yfir bekk úr steypu. Verkið kallast RAW PURENESS—SELF LOVE og er eftir Katrínu Ingu Jónsdóttur Hjördísardóttur. Við upplifun verksins var ég færð inn í einbýlishús mögulega staðsett í Garðabænum. Ég var ekki viss um hvort að hér væri á ferðinni kaldhæðni eða grafalvarleg skilaboð um mikilvægi þess að stunda sjálfsást. En parað með verki Melaniu virkar það eins og einskonar refsing eða sjálfshatur. Sjálfsástin sem ég stunda persónulega heima hjá mér á þriðjudagskvöldum er orðin þrúgandi, á samt sem áður rétt á sér í sínu eigin rými sem inniheldur reyndar enga gæru. Hér virkar hún kaldranaleg, jafnvel kaldhæðin. Er hún það? Þetta er ekki sýning með svör. Kannski er sjálfhverft að stunda sjálfsást á gæru og kannski er virk iðkun sjálfsástar eina leiðin framávið, það er erfitt að segja. Það gildir þó einu að báðar hliðar eru hlutar samfélags skynjandi vera og það er leyfilegt að draga iðkunina í efa og virða hana fyrir sér í stærra samhengi.

Með þessu sniði leika sýningarstjórarnir sér með innhverfa og úthverfa þætti mannlegrar tilveru. Það er erfitt að fóta sig, að ná fókus í tilverunni og um leið og ég náði fótfestu í einu verki var mér kippt úr henni í skiptum fyrir önnur skilaboð, fleiri sögur og enn fleiri verkefni.

Rúnars Arnar Jóhönnu Marínóssonar

Rúnars Arnar Jóhönnu Marínóssonar

Gígja Jónsdóttir

Gígja Jónsdóttir

Andrea Ágústa Aðalsteinsdóttir

Andrea Ágústa Aðalsteinsdóttir

Anna Wojtyńska og Wiola Ujazdowska

Anna Wojtyńska og Wiola Ujazdowska

Á neðri hæð Hafnarborgar birtist slík upplifun mér með skýrum hætti: tár, leikur og náttúra fá þar að raungerast í sama rými. Í verki Andreu Ágústu Aðalsteinsdóttur Eldur og flóra brennur náttúran vegna gróðurelda en Við þörfnumst öll sólar leggur áherslu á hinn glóandi eldhnött sem veitir okkur og öllu lífríki líf. Við grátum eins og Tárabrunnur minnir á en samt sem áður er rými fyrir leik í þessu samfélagi skynjandi vera, þar sem leikföng geta öðlast líf eins og í verki Rúnars Arnar Jóhönnu Marínóssonar Sjúga og Spýta lifa og starfa.

Í innsta rými Hafnarborgar má finna tvö verk sem einnig leika sér með innhverfa hugsun og úthverfa tengingu okkar við náttúruna eða jörðina. Agata Mickiewicz er með textílverk sem kallast Schumann-ómun og er myndræn framsetning slíkrar ómunar. Schumann ómun á sér rætur að rekja til rafbylgja sem myndast út frá eldingum og eiga sér stað víðs vegar á jörðinni. En slík ómun samkvæmt ýmsum vefheimildum (sem ég get þó ekki staðfest að séu áreiðanlegar) hefur róandi áhrif á líkama okkar. Í sama rými er mynbandsverkið Upphafið í eimingarflösku: í myndbandinu er litríkum formum varpað á ófrískan maga, sem eflaust táknar upphaf og nýja byrjun og litlir kollar eru dreifðir um herbergið og gefst gestum kostur á að hugleiða við handleiðslu raddar sem hljómar í rýminu. Þessi pörun verka var einstaklega vel heppnuð og kallar á mikla umhugsun. Annars vegar er geta okkar til að slaka á og róa okkur sjálf og hins vegar er hin mögulega geta náttúrunnar til þess að hafa slík áhrif á okkur utan frá.

Heildarskynbragð sýningarinnar er yfirþyrmandi. Þó er yfirþyrmandi heldur neikvætt orð yfir upplifun mína sem best væri lýst með áreynslunni við að reyna að velta fyrir sér mörgu í einu. Og þar sem það er ekki nauðsynlega áreynslulaust að fara á listsýningu þá rann upp fyrir mér að mögulega eru ein skilaboð af mörgum sem taka má með sér af sýningunni þau að svoleiðis séu samfélög í raun og veru.

Í viðtali við Víðsjá lýsir Wiola samtímanum eins og að vera með marga glugga í vafranum sínum opna í einu sem passar vel við upplifun mína af Samfélagi skynjandi vera. Það var sem ég væri að reyna að ná utan um margar mismunandi hugsanir í senn, (sem vissulega kemur oft á tíðum fyrir mig) nema að í sýningunni var sú upplifun sett í efnislegt form og það heppnaðist einkar vel þegar ég náði að sleppa tökum á því að reyna að finna einn rauðan þráð, þema eða eitthvað eitt haldreipi sem myndi leiða mig í gegnum sýninguna.

Hugarfarið sem ég þurfti að temja mér við að melta sýninguna var þar af leiðandi gerólíkt því sem ég hef þurft að temja mér í minni eigin akademísku hugsun. Frá minni eigin reynslu af heimspeki að dæma, eina akademíska sviðið sem ég hef sjálf reynslu af, er ómögulegt að taka fyrir Samfélag skynjandi vera í einu verki. Það hefur verið gert en oftar en ekki er það í formi doðranta sem spanna mörg hundruð blaðsíður og eru verk sem taka lífstíð að lesa og botna eitthvað í. Því takast nútíma heimspekingar oftast á við sitt eigið sérsvið. Stóru spurningarnar eru smættaðar niður í viðráðanlegar einingar og tengsl þeirra á milli er svo hugsuð sem eining í sjálfri sér. Flokkanir og skilgreiningar gera viðfangsefnið viðráðanlegt, skiljanlegt og mótanlegt.

Út frá upplifun minni af því að hugsa um allt í senn, túlka ég lokaorð sýningaskrárinnar „Það má merkja að einlægur samhugur og róttæk samkennd, fremur en rökhyggja og vísindi, veita okkur inngöngu í samfélag skynjandi vera“ sem boð um að sleppa taki á flokkun og skilgreiningum vísinda og rökhugsunar, leyfi til þess að sjá einstaka sögur í stærra samhengi og í beinum tengslum við aðrar.

Þannig stígur sýningin út fyrir rökhyggjuna sem oft helst í hendur við flokkun innan vísinda og fræðimennsku og tekst á við nútímann í formi margbreytileika innan sama rýmis. Þannig má líta á markmið sýningarinnar ekki sem andspyrnu gegn vísindum og rökhyggju heldur sem boð um að stíga út fyrir fræðilegu takmörkin sem vísindi og fræðimennska verða að setja sér og sjá verkin sem hluta af neti eða einfaldlega sem Samfélag skynjandi vera.

Eva Lín Vilhjálmsdóttir

Ljósmyndari: Kristín Pétursdóttir

- [1] https://hafnarborg.is/exhibition/samfelag-skynjandi-vera/

- [1] Tekið úr sýningarskrá

- [1] https://www.pressreader.com/iceland/frettabladid/20210908/282080574951335

- [1]https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/news/gallery/schumann-resonance.html

- [1] https://www.ruv.is/utvarp/spila/vidsja/23618/7hquuc