Confronting Surfaces

Confronting Surfaces

A bright colored tracksuit hanging from the ceiling is slowly turning as if an invisible air stream were spinning it around. When moving closer to the work I realise that the tracksuit’s print is an actual print of the tracksuit itself laying flat on a wooden floor. A meta-view of a tracksuit. A fashion garment staged as an art piece. This work, together with others, is a part of a new exhibition at Skaftfell Art Center in Seyðisfjörður which brings together works by American visual artist Cheryl Donegan (1962) and Swiss visual artist Dieter Roth (1930-1998).

The exhibition was curated by the director of Skaftfell, Gavin Morrison, who saw a resonance between Roth’s works and Donegan’s contemporary printing methods. A resonance especially apparent in Dieter Roth’s later years which he mostly spent in Seyðisfjörður producing innumerable prints, drawings and books.

When asked, Morrison explains he finds that both artists through experimenting with content and printing techniques engage in self-reflected conversations on the aspect of printing and publishing as a strategy of art.

Donegan‘s fabric pieces are exhibited hanging from the walls and from the ceiling and laying on tables, in-between table displays showing Roth’s books and sketches. In fact, the exhibition consists in full of Donegan’s three tracksuits, four wall pieces made by dyed fabric, one large wall banner which stretches out onto the floor, one video work and three textile works bound together as books. All of Donegan’s works are interwoven with six tables displaying Roth’s heterogeneous works such as books, prints, notes, drawings, diary entries and nine pixelated newspaper cut-outs on a wall.

Cheryl Donegan, Banner (Light Blue Gingham), 2014-ongoing. Photograph: Mary Buckland/Skaftfell

Cheryl Donegan, Banner (Light Blue Gingham), 2014-ongoing. Photograph: Mary Buckland/Skaftfell

On one of June’s last days I called Cheryl Donegan. She was back in her home in New York after having visited Iceland and Seyðisfjörður to set up the exhibition at Skaftfell. To begin the conversation, I asked her to introduce us to her practise.

When I was in art school, I was always painting. I was determined that I was going to be a painter. It was not until after my second degree that I picked up a camera and that was what I got famous for in the 90’s. The residue of video art is still in my work today in form of digital technology. At this point technology is blended so thoroughly into my work that now I am doing painting, printing and using digital and craft means. In a way I feel that I have found my way back to painting through these interventions.

By mixing digital methods with analogue craft Donegan creates works in which methods and styles from high tech and low tech meet – digital means meets physical craft.

I have developed a set of methods by combining digitally printed fabrics and craft techniques like dyeing and printing such as primitive forms like resist dyeing and my own adapted methods from batik. This combined with what I call an ecology of images which comes from the world around me: photographs I take, imagery that I am attracted to online, low-end consumer imagery and things I find in everyday life such as clothing and patterns. I am always collecting images and reusing them again and again.

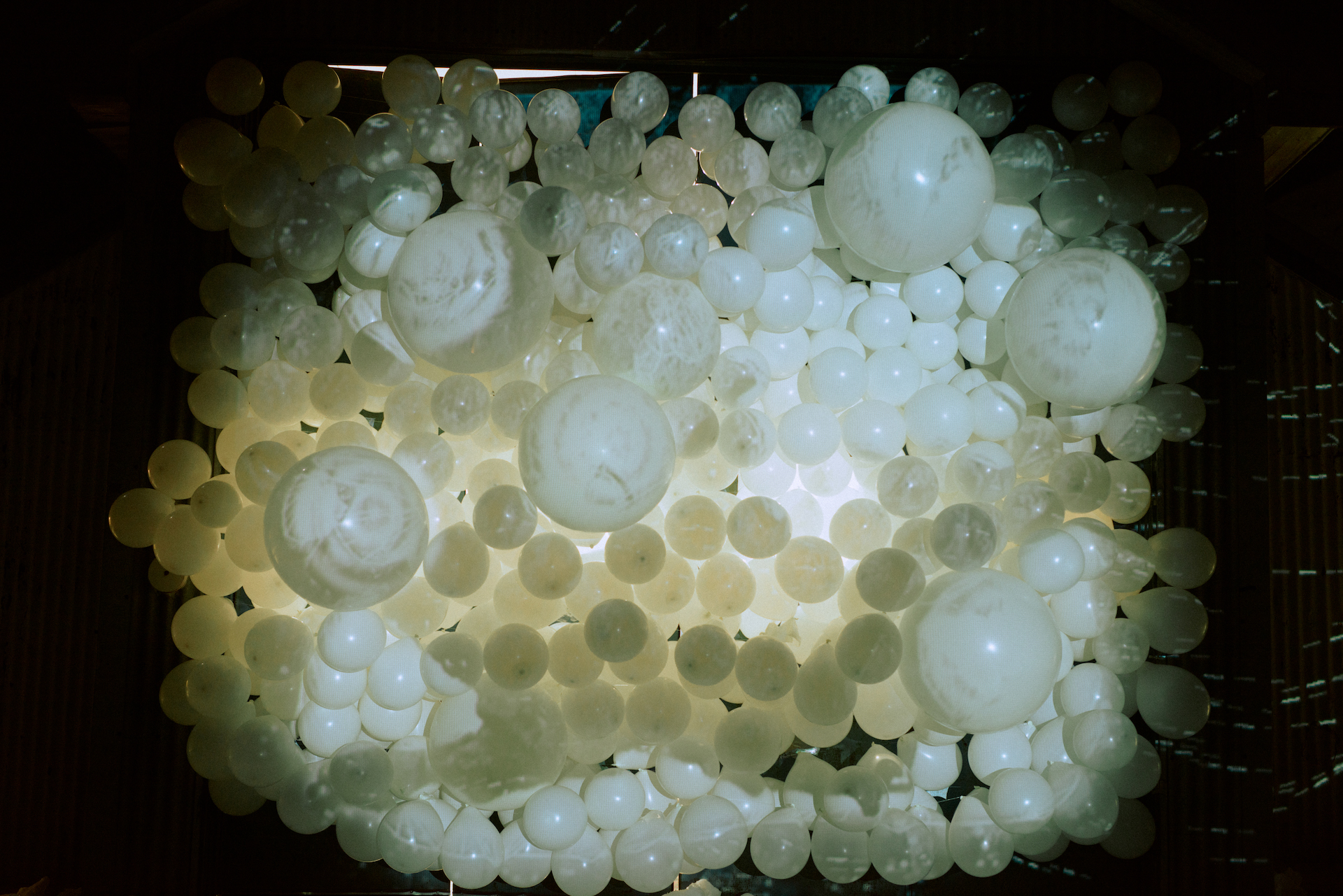

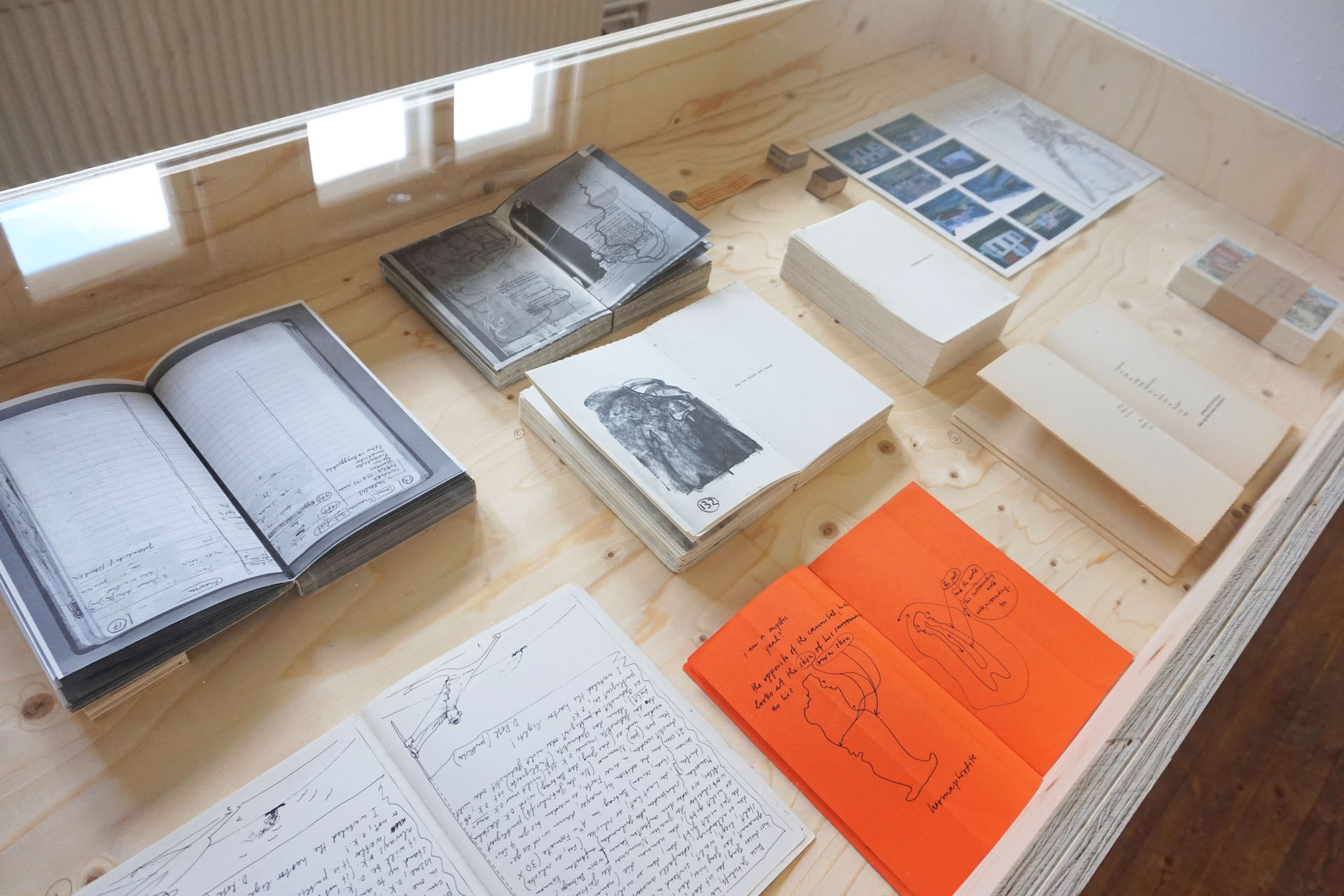

The printing and publishing practice seems to be the common ground between Donegan’s and Roth’s works. In one of the glass displays showing Roth’s works I stumble upon a stack of illustrations very simplistically piled up revealing only the top image. This pile symbolises the quantity of Roth’s works and it might suggest the challenge that the curator had to face when dealing with Roth’s massive production.

On a table, fourteen books titled either ‘dieter roth’ or ‘dieter rot’ and all numbered differently: ‘dieter roth 3’, ‘dieter rot 20’, ‘dieter roth 12’ are displayed. Flipping through the pages of these books I understood that this format was for Roth a way of documenting his own practice, other people’s art, old newspapers articles, cartoons, sketches, prints and geometric figures. One book is even showing a collection of Roth’s own books. A book on books!

Installation view, Dieter Roth. Photograph: Mary Buckland/Skaftfell

Installation view, Dieter Roth. Photograph: Mary Buckland/Skaftfell

When asking Donegan about her specific interest in printing she quickly connects it to her practice as a painter.

The recent history of painting is printing. I see a heritage of especially American artists dealing with reproduction and doing it in a way that is very much involved with “the hand” and the idea that you confront a surface not only by marking it, but by doubling it, repeating it. Working directly with fabric is for me the most influential. For instance with dye, the saturation of the fabric. The colors are not just ON the surface, they are IN the surface.

Walking around in the gallery space Donegan’s interest in colors is apparent and one work in particular stands out in the exhibition. Peels (2018/2019) has the shape of an oversized book and each of its pages is a dyed piece of fabric. The textile is thickly saturated with layers of color and the shapes vary from geometrical figures to freely sketched motives.

Cheryl Donegan, Peels, 2018/19 (Livre de Peinture). Photograph: Mary Buckland/Skaftfell

Cheryl Donegan, Peels, 2018/19 (Livre de Peinture). Photograph: Mary Buckland/Skaftfell

Cheryl Donegan, Flaps, 2019 (Livre de Peinture) Photograph: Mary Buckland/Skaftfell

Cheryl Donegan, Flaps, 2019 (Livre de Peinture) Photograph: Mary Buckland/Skaftfell

Donegan connects her interest in colors with a childhood memory. Big books of wallpaper samples would be scattered around in the house where she grew up as her mother constantly had plans to redecorate and get new wallpapers on the walls.

My interest comes from the fantasy of getting lost in different worlds of color and textures. As with a page in a wallpaper book, each page in “Peels” represent a possibility, a bigger world, a different world. The pages are samples of possibilities! I remember having a lot of aesthetic pleasure looking through those thick books of wallpaper and feeling their patterns. I have these sensual memories of laying on my stomach in the living room turning these big pages of a book. Talking about low-tech, right?

In recent years Donegan has been working in the cross-field of art and fashion. Working with printing and dyeing of fabric Donegan found herself beginning to create actual wearables and garments. The three tracksuits exhibited in Skaftfell are all in strong signal colors and the prints are made by images of other tracksuits and fabrics. The caption next to the tracksuits informs that an „endless edition“ is available for sale on the website Print All Over Me, an American website to create and order custom printed garments.

Donegan highlights that the time we are currently living in is a time of distribution. From Donegan’s childhood in the 1960’s the world had seen a shift in the distribution structures from being a one-way function to today’s flow of creation, sharing and distribution in-between consumer and creator constantly blurring lines between the two.

One of the positive effects of social media – perhaps the only I can think of – is that today people can make things together and teach each other how to do things by sharing the process. Distribution is not going away, so let us use it to share things instead. I am not the top of the totem. I am a part of a system and that is the motive behind my art. That is what I am interested in!

Nanna Vibe Spejlborg Juelsbo

Skaftfell Art Center’s website http://skaftfell.is

Cover picture: Cheryl Donegan, ExtraLayer Tracksuit in Cracked, 2016 Print on demand, endless edition and Cheryl Donegan, Flaps, 2019 (Livre de Peinture). Photograph: Mary Buckland/Skaftfell

On display and for sale are also a collection of zines created by Cheryl Donegan and her friends.

As a side to the exhibition, Dieter Roth’s installation Húsin á Seyðisfirði, vetur 1988 – sumar 1995 [Houses of Seyðisfjörður, winter 1988 – summer 1995] is exhibited in Angró – a harbor building close to Skaftfell. This exhibition is made in collaboration with the Technical Museum in East Iceland.

Cheryl Donegan prints are purchasable here: www.paom.com/collections/cheryl-donegan