A Violent Absurdity: Valheimur at Hverfisgallerí

A Violent Absurdity: Valheimur at Hverfisgallerí

Valheimur – a world is created, one that has semblances to our natural order and the social stories our cultures echo, yet is a product and figment of artistic imagination. In Sigurður Ámundason and Matthías Rúnar Sigurðsson recently opened exhibition at Hverfisgallerí, surreal narratives collide between the boundaries of reality and the imaginary in a combination of color, pencil, and stone. The artists, Sigurður and Matthías, shared their perspectives with me.

Sigurður: We know each other very well and for a long time we have been following each others work and process. Both of us are very diligent and patient with our practices and have a taste for detail. The day before the opening Matti mentioned it sort of felt like walking inside a hall of a palace of some weird wizard in another dimension. I guess that explained it best for me too.

Matthías: Me and Sigurður have been friends for a long time… I think they [the works] have many things in common and some differences as well. Drawing is important for both of us. The subject matter of our work is similar. It comes from the same place.

S: Drawing comes extremely naturally to me, it was a big part of my childhood. I would draw in class instead of paying attention and much of my spare time I would dream of stories to make into novels or films. When I graduated from the Art Academy in 2012 I got into large renaissance paintings and wanted to capture the epic and romanticism of those works, but I knew I had to do it in a different fashion than them, because now it’s the 21st century and you have to speak about your own time.

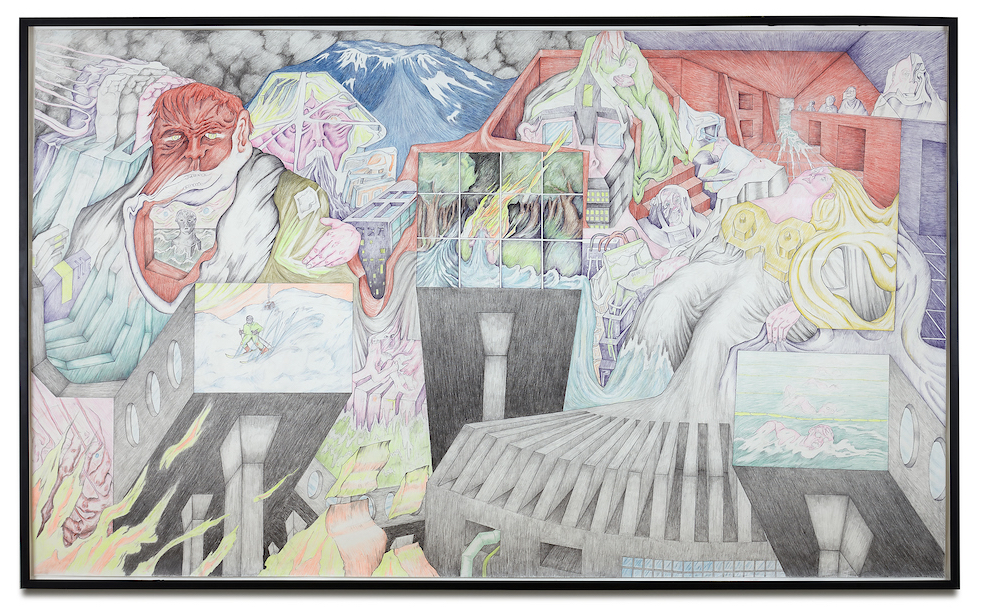

Sigurður´s compositions are fantastical in their perspectives and don’t literally “make sense”, combining often confused narratives. A snapshot of the imagery he throws together in his drawings: machinery, mystical waves, staged home scenes, snapshots of photographs, a beach, skyscrapers, mountainous landscapes, larger than life godly figures, a classroom, a road, distorted cars, skulls, and endlessly reiterating man spurting blood out of his chest, a swimming pool, graphic flames, a woman with child, a headless man. The list goes on.

S: It’s always hardest for me to start on a drawing, if it doesn’t begin well I get sceptical and will often erase and start over until the figure or landscape I’ll be basing the work on feels right. I usually draw the outline of a head or the eyes and if I don’t like the shape I don’t carry on with it, instead I just search until I draw something I can work with. Because I never do sketches beforehand and every piece is in a way spontaneous I find it important to feel connected to the first stages of each work. Later on when the work is taking shape and starting a life of its own, the process feels kind of like puzzling a work all together, one scene or figure at a time, or playing chess with myself or with the artwork.

The pencil strokes are wild and intense up close, but appear smooth and refined at a distance, like a painting. Warped perspectives draw you into the center of the work. Vaguely recognizable structures morph into a new scene and different perspective, the objects all connected by a never ending pencil line.

There is a violence to this work, both in its content and subject, and in its form, from the chaos to the splitting and distortion of recognizability. One form flows into the other, creating, informing, determining, and coexisting with all other elements of the work. Where do these creations stem from? From the inner depth of his thoughts? An alternate reality of endlessly repeating iterations that melt together into a soup of associations.

S: I hate violence in real life, obviously, but I find it different in art. I think there is a demon or demons inside of us all and we need to speak about them. By talking about them out loud we in a way diminish the power they have on us. I like the idea of normalising or talking about our flaws and weaknesses. I for instance have had a huge anger problem; I am OCD and I often have a minority complex over the most trivial things. I want to speak about these things because that is what is underneath my exterior, what bothers me and prevents me from happiness. And in a sense I think art is here for this, or at least partly. I also think that people can relate to it because they also have their demons and/or witness them in others. The absurd most often represents emotions in my work, possibly because emotions make everything absurd, life is extremely simple but made extremely complicated by our perplexing human nature. I’d like to point out that in all of my works there is always (or mostly) a force of hope as well to balance against the aggressions.

Sigurður´s drawings feel like what dreams would be if they were pulled out of subconscious into reality, into a tangible image, a blurring and melting of one form into a next adventure that you’re not quite sure where ends or begins. These fantastical narratives are almost eeries at times. They contain moments of a distinct structure that disappears into the whole of chaos, a black hole of colors and shapes. Chaos, yet it is all perfectly connected, in its pristinely illogical order. There is beauty in something so illogical, incomprehensible.

S: I always have my eyes open for anything I find stunning or interesting, sometimes when I hear an intensely beautiful symphony by Beethoven or Arvo Part I feel like I want to be apart of it and that often translates into the epic or majestic in my work. The same goes for anything else that affects me; weather, its urban decay, or a sunset over a mountain. The aggressive notes of my work often stem from my own inner angst. My day to day problems are not huge compared to those who are truly suffering but I do find it extremely important for every human being to deal with their problems if they’re big or small.

What does this exaggerated and extreme nature, the agony in these drawn narratives, say about the human condition? – in that these works are more about our own agony, our own mental turmoils, nightmares, brought out onto paper.

S: There’s always some sort of commentary about humanity and the human experience, both the hardships and pain that can be found in the mundanity of everyday life and the victory that can arise from choosing the “right path”. Visually I find myself drawn to epic scenes, brutalistic architecture and science fiction as well as disfigured beings that are somehow morphing into their surroundings. Time often seems to play apart in my work and duality especially. I like for instance the duality of the extreme versus the casual and mixing them together, perhaps in order to underline the importance of what we call mundane or “not important”.

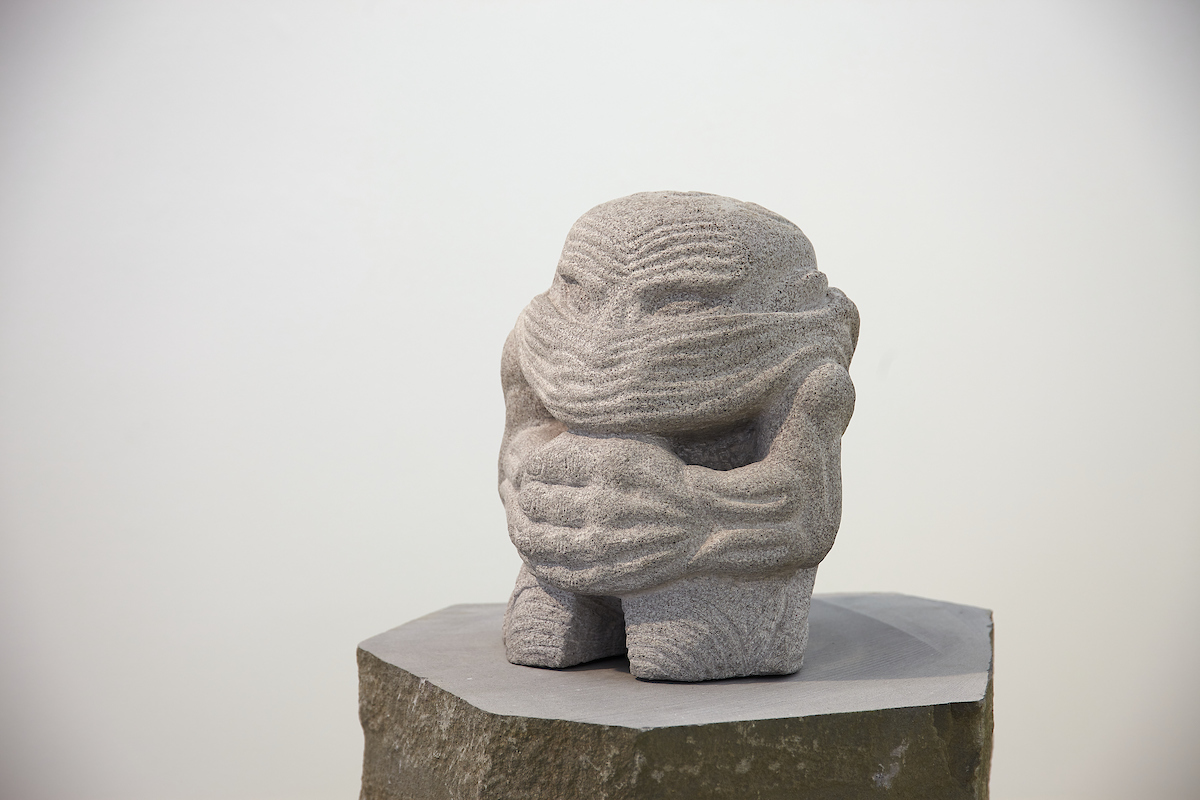

Matthías’ sculptures are equally fantastical and brutalistic, in their own sense, and open up for narratives of absurdity as well, albeit a bit more quietly. They reference to gods and mythical stories, tribal, tombstones, totems, places of worship. One lies on the ground, like a ruin, suggesting something archeological in nature. There is a solemness to the sculptures, but there is also a certain humor to them, like the absurdity of Sigurður’s work.

M: First I find a stone to carve. I sketch and draw so that is where I get the ideas for my sculptures most of the time. Sometimes I plan what the next sculpture will look like and then I might get a stone of a specific type cut in specific dimensions. Other times I take a stone that I have found lying around somewhere and see what I can do with that. Since carving is all about removing excess material, the idea must fit inside the stone. Usually I try to memorize the idea I want to carve instead of having a drawing in front of me, unless it’s on the stone itself. I like drawing the sculpture when I’m not carving it, to keep the idea in my mind. I always carve outside and I use every tool that is available to me, such as grinders, hammers and chisels. I use a mask so I don’t inhale the dust. Carving stone is time consuming and it can also be hard work so it’s all about patience.

It is as if these totems speak to generations from another time, but what time? A mythic and epic created from fantasy, from the mind. Each viewer will make their own cultural associations; perhaps some connect them to the grotesqueness of the gothic period, like gargoyle figures.

I like to combine the characteristics of animals, objects and humans to make anthropomorphised characters. They can resemble those in a folk tale or some mythology or maybe a movie. I have always had an interest in mythology and stories of the supernatural so it wouldn’t surprise me if I draw some influence from that. It can be hard to say where the influence comes from, but it must come from life and my experience of that.

The sculptures have a historical, monumental feel to them, like they are out of some sort of Viking or mythological history. The solid nature of stone contains an ominous presence in the exhibition space.

M: One thing I like about stone carving is the permanence. The stones themselves are old, some of them have been here for millions of years. The sculptures will also be here for a long time in any case. When looking at stone carvings from the past the sculptor is usually forgotten and it’s as if the sculpture has always been there. I sometimes go to this fantasy of the future, imagining the sculptures in a different time period…

S: Mythology is definitely a factor that joins our work together. Both of us are interested in modern and ancient mythology and creating our own versions of these. Also translating our own personal problems with the use of mythology. We are also both using old techniques and trying to create and understand something new with them.

Daría Sól Andrews

Valheimur at Hverfisgallerí is open until October 12, 2019.

Photo credits: Vigfús Birgisson

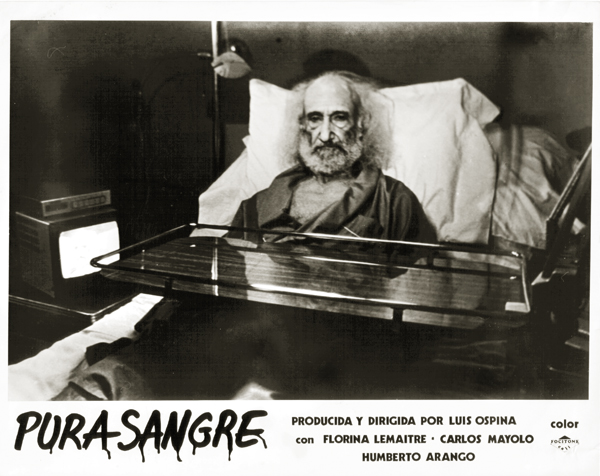

Christoph Büchel’s Barca Nostra by the sandwich bar in the Arsenale.

Christoph Büchel’s Barca Nostra by the sandwich bar in the Arsenale. The Swiss sculptor Carol Bove was this years’ discovery of the journalist. Her sculptures are a twist of the clean lines of modernistic sculptures where she uses the aesthetic and semiotics of the dent, the bend, the pull, the roll, the squeeze and other types of transformative actions as her own language. The color palette creates the illusion that the steel she uses is really soft and flexible material and the sculptures demand that ones’ body, eyes and mind glide around the work.

The Swiss sculptor Carol Bove was this years’ discovery of the journalist. Her sculptures are a twist of the clean lines of modernistic sculptures where she uses the aesthetic and semiotics of the dent, the bend, the pull, the roll, the squeeze and other types of transformative actions as her own language. The color palette creates the illusion that the steel she uses is really soft and flexible material and the sculptures demand that ones’ body, eyes and mind glide around the work. Nabuqi is a young Chinese artist that also uses steel in her work but in a different way. She uses found objects and creates stages where she plays with simulations in an artistic research on how we connect to our environment. In the work Destination from 2018 she uses an advertising billboard with a photoshopped picture of a paradise decorated with palm trees but also with fake plants in a work that plays with the interplay of fantasy and simulations. Promises are given without the opportunity to be able to fulfil them.

Nabuqi is a young Chinese artist that also uses steel in her work but in a different way. She uses found objects and creates stages where she plays with simulations in an artistic research on how we connect to our environment. In the work Destination from 2018 she uses an advertising billboard with a photoshopped picture of a paradise decorated with palm trees but also with fake plants in a work that plays with the interplay of fantasy and simulations. Promises are given without the opportunity to be able to fulfil them.

The Murano glass sculpture of the Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga in the Arsenale was an interesting investigation into a local raw material that played an important part in the colonial trade history. It reminded the journalist of Otobong’s work about the glimmering mica material at the Berlin Biennale in 2014. Mica is the material that made the church towers of Europe glow in the sun while in her home country it made the ground glitter. As the journalist has been seeing a lot of installation and sculptural work of Otobong in the last few years it was a pleasure to see Otobong’s works drawn on paper in the Giardini part. Otobong’s contribution won a special jury prize together with the work of Mexican artist Teresa Margolles.

The Murano glass sculpture of the Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga in the Arsenale was an interesting investigation into a local raw material that played an important part in the colonial trade history. It reminded the journalist of Otobong’s work about the glimmering mica material at the Berlin Biennale in 2014. Mica is the material that made the church towers of Europe glow in the sun while in her home country it made the ground glitter. As the journalist has been seeing a lot of installation and sculptural work of Otobong in the last few years it was a pleasure to see Otobong’s works drawn on paper in the Giardini part. Otobong’s contribution won a special jury prize together with the work of Mexican artist Teresa Margolles. The Silver Lion went to a young artist the jury considers very promising:

The Silver Lion went to a young artist the jury considers very promising: