“Between people and places”: An Interview with Gavin Morrison

“Between people and places”: An Interview with Gavin Morrison

My first meeting with Gavin Morrison was brief, sparked through his research on Donald Judd in Iceland, and its connection to the Living Art Museum. Morrison visited the museum, via Ingólfur Arnarson, in hopes to collect information related to a group exhibition in 1988 Judd had participated in and what remained of this moment in Nýló´s archives. An article about this history titled “Donald Judd and Iceland” was later published for the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, 2018. The article explores the narrative circulating Judd´s activity in Iceland, what led to those explorations in site, place and expanses, and is not so far removed from the way Morrison (or others) ended up here, working with artists more permanently.

Fast forward and Gavin is now Director of Skaftfell – Centre for Visual Art in East Iceland. In this interview Gavin considers his relationship to Iceland, and current role through a global perspective, with reflections on the movement of people to places and the connections made in between. For him, these things become a site for placing local or regional contexts amongst an “international vernacular” — a curatorial practice embedded in cultural history.

You are a curator (also a writer, publisher and collaborator). Where and how did this begin?

I can’t say with any great certainty when the beginning was, but while studying philosophy at Edinburgh I somewhat accidentally established Atopia Projects, a curatorial and publishing initiative with an artist friend, Fraser Stables. We’d both been concerned with similar problems, an anthropological understanding of how we inhabit contemporary spatial locations. He was approaching this through art and I through writing. We expanded our dialogues by inviting others to join in, which evolved into publishing a journal of sorts. This was around 1999 and since then we have kept an erratic schedule of releases making books, exhibitions and other published forms. Working this way, in the collaborative approach and realizing ideas in different forms, made me very interested in the ways those aspects affect the ideas expressed.

This resonates as a key moment and meeting point, how did it translate into making exhibitions?

I think through this I became fascinated in the exhibition format, its ability to present objects and ideas in non-linear, disjunctive and discursive relationships. I love the primacy of the visual medium and to make exhibitions that can only be understood in that form. That is not to say that I am not equally committed to writing and books, I enjoy the luxury of being able to work through various modes of thinking reliant on the particularities of those forms. More recently I have fallen into collaborations with artists. I don’t think of myself as an artist and I’m not sure exactly what those things are that I have made with artists, such as on-going project A History of Type Design with the Scottish artist Scott Myles or a series of prints with the Norwegian artist Arild Tveito, they seem to fall between designations, they are not exactly artworks, more allegorical emblems in a type of thinking, one which can only be expressed through a visual mode.

In what ways do you approach working with different artists?

I try to respond to artists and their work in a way that is consistent with their intentions, and try to avoid using artists to illustrate an idea which I may have. Where it is easy to fall into a didactic approach within the curatorial role, it is undoubtedly more interesting and rewarding to engage with the breadth and the intentions of an artist’s practice. I am fortunate that this approach has resulted in extended relationships with various artists. It is wonderful to be part of a conversation about the work. It is these types of relationships that have led to creating those ‘allegorical emblems’, where discussion of shared interests makes for something new that couldn’t exist with either of the individuals solely.

Skaftfell – Centre for Visual Art, Seyðisfjörður

From Scotland, to the south of France, now Seyðisfjörður; what precipitated your connection to Iceland and projects here?

I’d been living around Marseille and on Corsica for a number of years before here. I first came to Iceland in 2001, on a three day stop-over to Houston to undertake a research fellowship at the Museum of Fine Arts there. An artist who I’d been working with in Scotland, Alan Johnston, was a highly vocal advocate for artists in Iceland, and he connected me to various people in town. It was an incredibly brief period but I made connections with artists, writers and curators that have continued to this day. I found there to be a generosity, both personally, and in thinking with those I got to know. That generosity, I think, arose from the concentration of the art scene in Reykjavik. Almost immediately I started to work with the artists I had met and came back to visit regularly.

In 2010, I finally made it to Seyðisfjörður, I knew of the place through Birgir Andrésson, who had long implored me to make the effort to come here. After his death, I heard that Skaftfell had his former home for artists in residence, so I came to work for a month on curatorial projects. On the way I was stuck in Reykjavik for a few days, waiting for the wind to change, and blow the ash cloud from the erupting Eyjafjallajökull away from the flight path to Egilsstaðir. I had an incredibly productive time and was asked back a few years later as part of a project with Skaftfell, organised by Ráðhildur Ingadóttir. Following which I was invited to serve as the Honorary Artistic Director in 2015 for two years.

There are moments of movement, finding place and connection that sit at the forefront of your experience with art, and no less in your relationship to the island. What would you say were your first impressions of the art scene when you arrived?

I do wonder if I would have the same experience today arriving into Reykjavik as I did in 2001. The people I met at that time were eager to show and talk of their work. I doubt that has changed so much, but with greater connectivity between people and places and how Iceland has excelled in establishing itself within the art world, there is perhaps easier ways to make connections than showing up a studio door. It seemed that during each studio visit the artist would phone someone else, and I would go straight from one to the other not quite knowing who or what I was going to see. I did enjoy that more naive moment, where now the internet provides an avenue for perpetual research and forewarning. But at the heart of it, I think the Reykjavik art scene has retained its vibrancy and excitement. It is small. Small enough that everyone knows one another, more or less. And with that scale it means hierarchies can seem absurd or at least easily circumvented.

Coming from Scotland I was impressed that the museums would show young Icelandic artists. That seemed like a powerful acknowledgement that artists were of value and also that museums were part of culture not merely an accumulated history. Existing alongside this also seemed to be an ambivalence to art history amongst the artists. I don’t mean that there was an ignorance towards history but rather they didn’t seem bound by it or feel it as a burden. Instead there was an ability to quote from it and reinterpret it. This also seemed liberating, it was as if there was a residual spirit of dada, fluxus or punk.

Even though Reykjavik is diminutive in scale it didn’t, and still doesn’t, feel culturally small. I suspect that is due in a large part to its cosmopolitan make up, both that it is welcoming of international artists who spend time there, either short term or for longer periods. But perhaps most notably is the way in which artists studying abroad return and their divergent experiences become braided with one another.

As new Director of Skaftfell, how are you positioning yourself?

I feel the curatorial position of Skaftfell comes with a certain mandate principally related to the context of Seyðisfjörður. It does not restrict the program to being local and provincial but is a point from which the curatorial view originates. In many respects Skaftfell is a custodian of the cultural history of Seyðisfjörður. The art center arose through the initiatives of a group of local artists and there always seems to have been a radical substrata to the art scene here. This history, of a group of artists in a particular place, looking out into the wider world suggests the mode of working — an attention to the local which informs a global perspective. It is a kind of international vernacular. This perspective is written into the material structure of Skaftfell. We maintain three buildings, the Skaftfell house, Geirahús and Tvísöngur: a traditional timber house converted into a bistro, gallery and residency through the design of Björn Roth (that draws influence from Dieter Roth); the diminutive and colourful home of the local outsider artist Ásgeir Jón Emilsson (1931-1999); and the concrete sound sculpture by German artist Lukas Kühne. Each building is a type of artwork, where inhabitation has creative potential. As custodians of this heritage we seek to find ways in which it can be celebrated and discover how contemporary artists can relate to and form their own legacies.

My current inspiration in this role comes from this inception, the initiatives of this group of local artists, through to its relationship with the diverse local community as both audience and collaborators. It is this particular vernacular that underpins the curatorial strategy — the view outward from Skaftfell and Seyðisfjörður, an undoubted international perspective but approached from the specifics of history, locality and geographies.

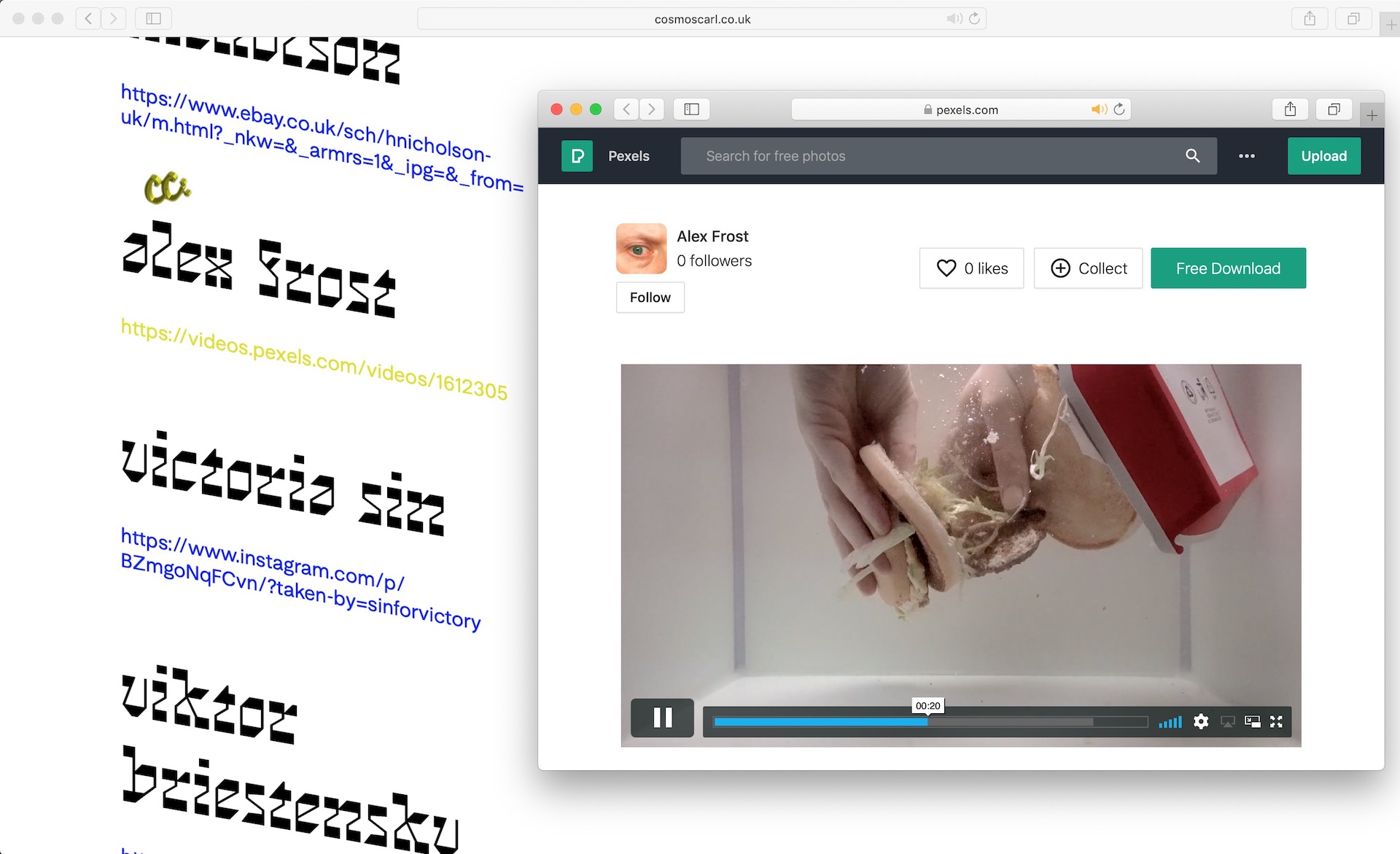

Still Images from the installation: Dieter Roth, Seyðisfjörður Slides – Every View of a Town 1988-1995, 1995

Still Images from the installation: Dieter Roth, Seyðisfjörður Slides – Every View of a Town 1988-1995, 1995

What is in store for Skaftfell regarding this summer’s exhibition?

This summer’s shows takes on Skaftfell’s history and potential directly by re-staging an installation Dieter Roth made in a harbour-side building in 1995. The work, Seyðisfjörður Slides – Every View of a Town, 1988 – 1995, an installation of six slide projectors which shows every building in town in the winter of 1988 and then in the summer of 1995. Was first shown in the town wide exhibition Á Seydi in 1995. This exhibition was organised by artists in the town and was an important precursor to the formation of Skaftfell. Our re-staging of the installation offers an opportunity for the town to look back at its history and consider the social changes since it was first shown. In conjunction with this installation we will also mount an exhibition in Skaftfell’s gallery, a form of retrospective of Dieter Roth’s book and published works, with the printed paintings and textiles of New York artist Cheryl Donegan.

Donegan and Dieter’s similar and divergent methods will provide a fascinating way to consider a shared utilisation of printing and publishing strategies between these two artists. For the exhibition, Donegan will present recent work in the form of clothes, paintings, videos, printed textiles, and zines.

What, in your mind, can an exhibition space become — and more specifically regarding Skaftfell?

I think that there is a particularity to spaces, one that can be felt acutely with Skaftfell. The conversion of the building establishes a functional and ethical position for the gallery. The ground floor of Skaftfell houses the bistro, with its library of Dieter Roth books, and from which a staircase directly leads to the gallery space on the next floor (and above the gallery is an apartment to be used for residencies and visiting artists). This arrangement echos the primacy of Skaftfell’s place in the local community. There is a porous relationship of Skaftfell’s function as a space of social interactions, which easily flow from the bistro to the gallery and back, and as a type of town forum, a place where discussions can be arise due to the work in the gallery, or despite of it. It is one of the most socially dynamic galleries that I know. This is the background to making exhibitions at Skaftfell.

Sometimes the purpose of the curator is to create the circumstances to let an accident happen. This type of purposeful ambivalence was partly what motivated our spring exhibition, Collectors. We wanted to create an exhibition in which the outcome was not something determined by curatorial oversight but was the expression of a local vernacular, an exhibition made by the local community. We made a general invitation to the people of Seyðisfjörður, that if they had a collection, irrespective of what it was or whether it was the result of purposeful collecting or accidental accumulation, that we would show it in the gallery. We wanted to create a situation where the town could show something of themselves to one another, something that perhaps was to an extent private. A type of self-portrait of Seyðisfjörður and also a means to consider the role of the gallery for the local population. The gallery does have that ‘power’ as being a part of the conversation in how a town thinks of itself. And it also has the capacity to disperse and re-orientate the curatorial ‘power‘ allowing for a plurality of expression.

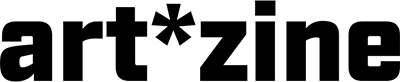

Installation view of the exhibition Collectors at Skaftfell – Center for Visual Art.

Installation view of the exhibition Collectors at Skaftfell – Center for Visual Art.

This thought of a plurality of expression is so relevant to both visual art and curating presently in the world, and although broad in consideration, why was it contemporary art for you?

I am excited that contemporary art lacks a functional purpose, with that it has the ability to change and adapt, to be whatever it wishes within any circumstance it finds itself. This malleability can also be taken advantage of, art being used as a surrogate and chorus-line, being made to fill in gaps of social provision and take on causes. I think my position is in part to help maintain its purposeful purposelessness, to allow for it to have utility as it wishes but always retain its autonomy.

Becky Forsythe

Gavin Morrison is a writer, curator, publisher and current Director of Skaftfell Centre for Visual Art in East Iceland. He previously served as Honorary Artistic Director there between 2015-2016 and was responsible for exhibitions including: Eyborg Guðmundsdóttir & Eygló Harðardóttir; Ingólfur Arnarsson & Þuríður Rós Sigurþórsdóttir; Unoriginal: copying, duplication and plagiarism in art and design; and solo projects by Hanna Kristín Birgisdóttir and Sigurður Atli Sigurðsson. Throughout his career, Morrison has held positions at and collaborated with various international institutions including Kungl. Konsthögskolan, Stockholm; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Osaka Contemporary Art Center, Japan; University of Edinburgh, Scotland; and most recently as Research Fellow at Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, USA.