A Mirrored Detritus and the Camouflaged Body : B. Ingrid Olson at i8 Gallery

A Mirrored Detritus and the Camouflaged Body : B. Ingrid Olson at i8 Gallery

I8 recently added B. Ingrid Olson (b.1987) to their roster of represented artists, a Chicago based artist whose intriguing practice can be placed somewhat ambiguously along an undefined axis of photography and sculpture. Olson´s exhibition at i8, Fingered Eyed, her first solo exhibition in Iceland, is compelling in its refined execution. Each of Olson´s pieces are intricately woven in a subtly connected thematic, bordering a limbo between a raw sterility that is contrasted by the warm, fleshy presence of the human body. Fingered Eyed is stark and directed, with a unique precision of vision that is wholly satisfying.

This exhibition works with an open and permeable vocabulary of sculpture, photography, a theatrical staging, and a focused detail on physical material. As Olson essentializes, a “bodily image contained by spatial cavities, or concavities.” At first glance, her sculptural photographs suggest something like papier mache, digitally distorted after the fact, the compositions so complex and confused. In fact, the meticulous moments are staged by the hand of the artist, captured at the blink of an eye, or rather at the close of a camera shutter. Crafted with a precise calculation, each photograph contains a different aim, a different intuition of gesture as she expands and contracts the body and its mirrored proximities.

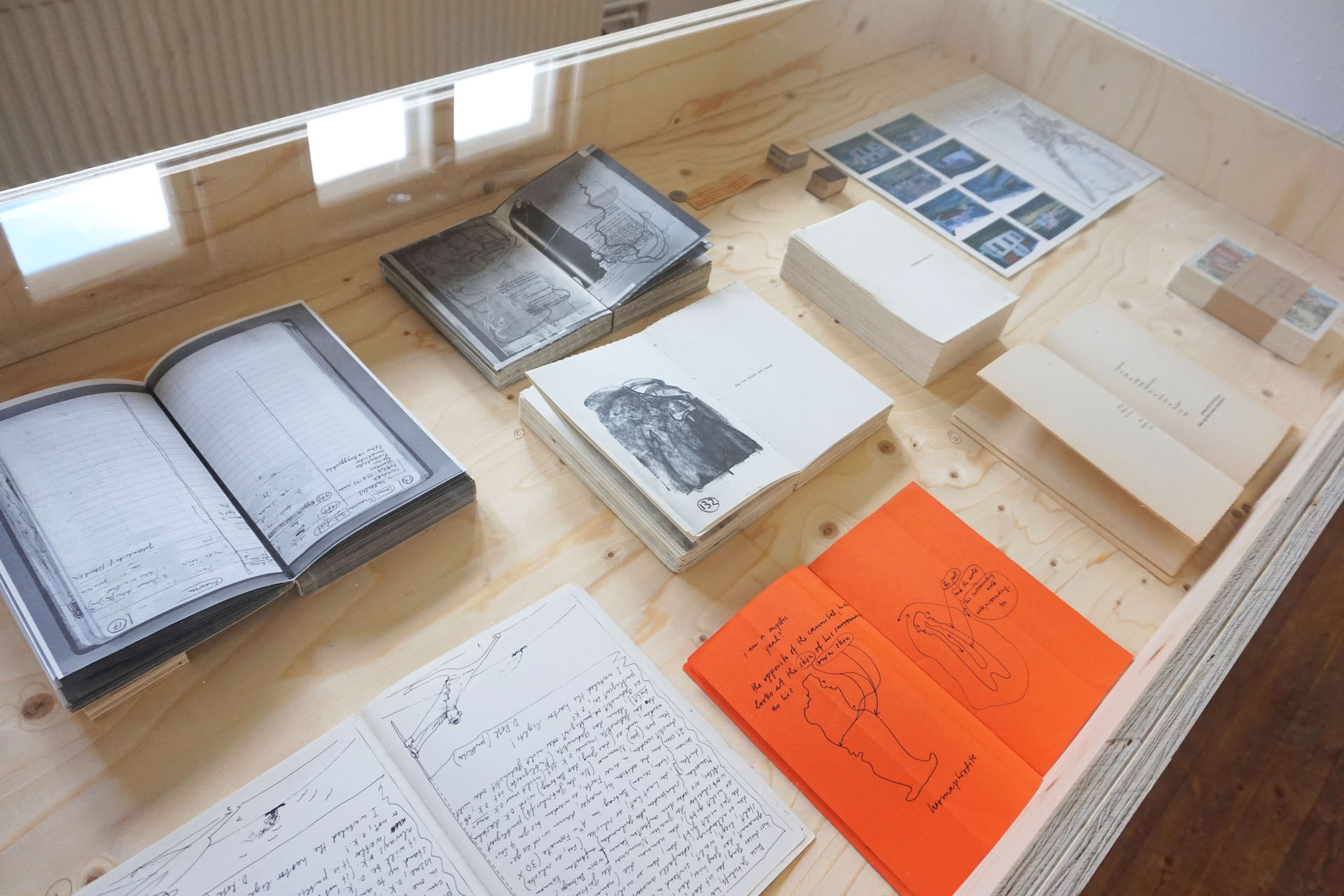

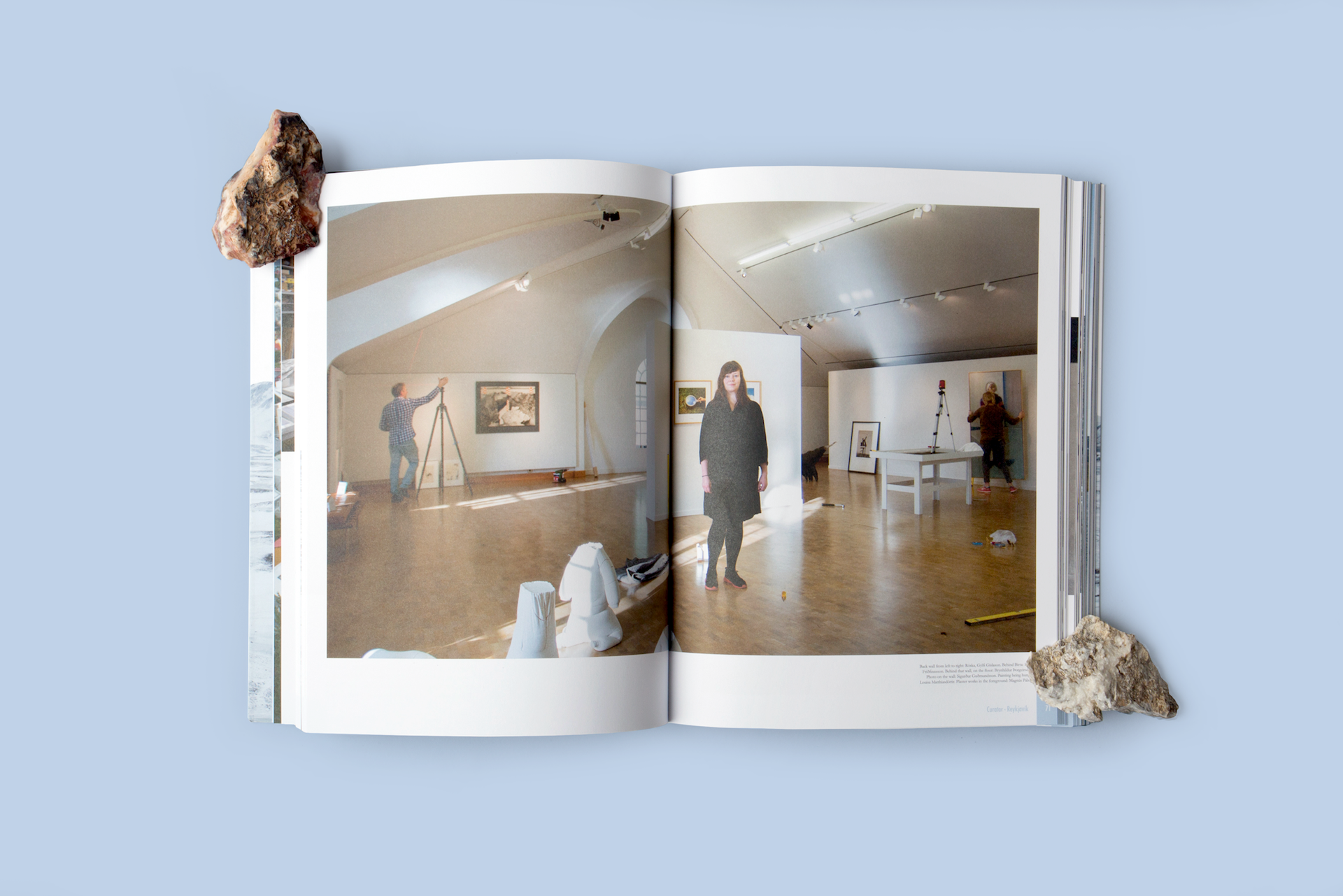

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Olson unpacks the process for me: “the work that appears to be primarily sculptural comes out of a series of forms that are actually designed to create images by way of light and shadow cast over the protruding edges and inward curving surfaces. Overhead lighting works on their structure to relay a shadow-image of a minimal, absent body. Though these works are not at all photographic technically, their relationship to light (both artificial and natural sunlight) does function as a parallel metaphor for photography, which at its root is described as ‘drawing with light’. And conversely, the works that can be easily referred to as photographic are also equally sculptural in their activity, structure, and presence. The pictures capture performative sculpting of the body and space, with handmade props or found objects that work to camouflage or conflate the figure with its surrounding space. The printed images are then again bridged into the sculptural by way of their deep Plexiglas frames that extend far into their frontal airspace, forming a simultaneous barrier and open container.”

These photographic objects (plexiglass, dye sublimation print on aluminum, MDF) extend out from the wall, surgical yellow, pasty tones interrupting the sterile gallery space. She calls these three works ‘blinders’, working with an analogous relationship to interior architectural space. “The deep sides become wall-like, in that they cordon off the recessed image from full view when approached from an oblique angle. They put limitations on the completeness of vision and dictate how much and when the framed image can possibly be seen. The frames work to orient the viewer towards full-frontal, conscious looking.” It is only when we come to face the object that we encounter the work within. Because of their physical walls, we cannot fully experience the sculptural forms unless facing them head on, entering them, almost. It is in this that Olson allows us to be alone with the piece, carving out a space from which a work and an experience emerges from within the depths of an empty wall. An object, out of moment, for us to privately revel in.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

The body is present throughout. Olson hides her face, but it is present. As she explains, “the body as ‘malleable construction’ has givens, but they can be adapted, changed, and altered. I think this quality of the lived-body is related to lived-architecture, in that there is the initial design of the space, versus the eventual built building that succumbs to time and changing circumstances. Bodies and buildings both need consistent upkeep and adaptation in order to fill certain changing roles, or needs. There is the given nature of things in the beginning—and then there is manipulated, altered, embodied experience.”

A finger over the lens. Mirrors smudged by bodily interaction. An oddly covered female crotch. Smaller sculptures dispersed along the floor and walls reference to knees, holes, body rolls, hips. A loose sculptural representation of an eye, also just barely noticeable in a photograph, imprints of kneeling, a place where two feet might once have stood. The gallery space is physically marked and molded by the body, the image taking a tactile form.

Each photograph, sculpture, and malleable form informs the other, Olson explains, in their difference in speed. “Images work with immediacy, quickly on the eye, whereas sculptural objects are much slower. The photographic images have a sense of simultaneous time inherent to them, inviting a mental jump to a past time and place. The sculptures are (questionably) ever-present, existing as objects to be encountered by the body, in the here-and-now. It is my hope that the sculptural will slow the photographic, and the photographic pieces will prod the sculptural components, causing them to shiver a bit.”

In the smaller sculpture works, the corporeal nature of craftlike fabrics, the delicateness of the cloth, for example, draws out a physical moment from the image. One sculpture is made out of light reflective paper, which she uses in her images as well to create shapes and distortion over her body. The photographic method is then brought out into an embodied form, into physical space, for us to engage and respond to.

When I ask B Ingrid from where she draws artistic influence, she tells me that she tries to “spend time with and approach things or ideas that I strongly dislike. Repulsion or anger is the opposite of attraction and affinity, so it only seems natural to try to find a point of entry into the uncomfortable or the unwanted so they can inform their opposites in some way, or at the very least so they create some itchiness by way of their difference.” And in fact, the harshness of this reflective paper, harnessing a sterile and extreme light, invokes a very specific and familiar feeling in the viewer. It is an uneasy feeling, an itchiness even, and we don’t quite know why. A prosthetic, surgical quality, invokes the naked, gritty, harsh lights of a hospital. Uncomfortably sickly tones and artificial body parts create a corporal form out of something mechanical. A shrine of the body, mixing physical and artificial, plastic and organic, natural and constructed. In this uneasiness we become distinctly aware of our own bodies, whether they are not quite surely still whole, amidst this chopping of others.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

In closing, I notice that a quarter of sales from an offset print in the exhibition will be donated to the American Civil Liberties Union and to Stígamót Education and Counseling Center for Survivors of Sexual Abuse and Violence in Iceland. Perhaps this is part of the derived implication, in Olson’s focus on the body and the unwanted, that our bodies are threatened, of not being sacred, ravaged, torn apart, manipulated. An extra layer for private reflection is unveiled, a space for us to consider a safe place for our bodies, where we revel in their beauty, uninterrupted.

Olson’s aim from this exhibition? Put simply, “to slow an image down, to create, in its ideal outcome, an image that will contain multiple readings, or entry points—to make an image that will only reveal itself fully over a longer period of time.” And successfully achieved, in intriguing fashion.

Daría Sól Andrews

Fingered Eyed is on view at i8 Gallery until August 10th, 2019.

Cover photo: B. Ingrid Olson, Eye, Camera, Body, Room, (Horizontal), 2019.

Photo credits: Vigfús Birgirsson

Photographs courtesy of i8 Gallery.

Artist’s website: http://bingridolson.com

i8 Gallery: https://i8.is

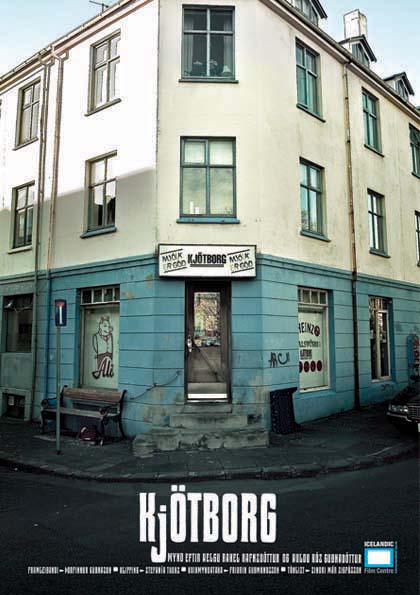

The Cornershop / Kjötborg (2008) poster.

The Cornershop / Kjötborg (2008) poster.

Sigurður Guðmundsson, Eggin í Gleðivík, Djúpivogur, 2009.

Sigurður Guðmundsson, Eggin í Gleðivík, Djúpivogur, 2009.