This year’s edition of Cycle Music and Art Festival is titled Inclusive Nation, and it aims to place the festival in a larger context, looking at what is happening in the rest of the world and reflecting on how countries and individuals deal with issues like immigration, integration and cohabitation of different cultures. Iceland has been isolated for many years, and just recently started to be a dream destination for migrants who choose Iceland for its nature’s stunning beauty and for the country’s welfare.

Sanna Magdalena Mörtudóttir of the Socialist Party, the youngest city council member and the first black woman in the Icelandic council ever, took part at the panel discussion Inclusive Flow at Iðno, and she unlighted how the homogeneous population of Icelanders is now facing a change: immigration is growing and cultures are getting mixed, the typical Icelander with blue eyes and blonde hair is no longer representative of the whole nation. However, Iceland had never really started any conversation about diversity, because it had never had to face this situation before. Cycle is taking place at the right moment: as immigration grows, racism starts to pop up here and there. About a month ago local newspapers reported an investigation about immigrants working in Iceland, showing to the Icelandic population a silent exploitation happening in front of our eyes.

Melania Ubaldo has been working on her personal experiences as victim of slight racism for quite a long time. The work consists of a huge collage of different canvas, assembled together through a long process, creating a dissonant unique piece in which the diverse parts find a kind of harmony despite their diversity. The bits of canvas sewed together are topped with a sentence written in quick movement “Is there any Icelander working here?”, a question the artist got asked while working, as she wasn’t Icelandic enough just because of her Filipino’s somatic features. Her work is part of the show Exclusively Inclusive, and it hangs on the wall of the Gerðasafn, just next to the reception, to contextualize the work in a physical place which recalls the one where the incident happened.

Meriç Algün, born and raised in Istanbul but educated in Sweden, lives between Turkey and Sweden, a living in the in-between condition which led her to explore concepts as identity and belonging. She contributed to Cycle with a series of billboards spread around the public spaces which report questions people got asked in the visa application forms to enter a foreign country. Questions like “Are you and your partner living in a genuine and stable partnership?” arise reflections about the travelers’ identity value, especially in the airports, places where privacy is suspended and the individuals are invasively checked and questioned, diminished, simplified to fit in a pre-established grid which will determine a person’s adequacy to enter the country. Airports fall under the definition of non places a category Marc Augé created to refer to those anonymous places of transition where the human beings just pass by without building any kind of emotional interaction with the surroundings, so that it doesn’t matter if you are entering France or Norway, in any case you’ll be asked “Do you speak english?”. This question also deculturalizes and reduces the values of the hosting country, affecting the experience people would get from it, emphasizing they are allowed to enter the country just as tourists, they are expecting to act as tourists, to have a touristic experience of the country, they are under control.

Melania Ubaldo, Er einhver íslendingur að vinna hér? (2018)

Melania Ubaldo, Er einhver íslendingur að vinna hér? (2018)

Meriç Algün, Billboards (2012)

Meriç Algün, Billboards (2012)

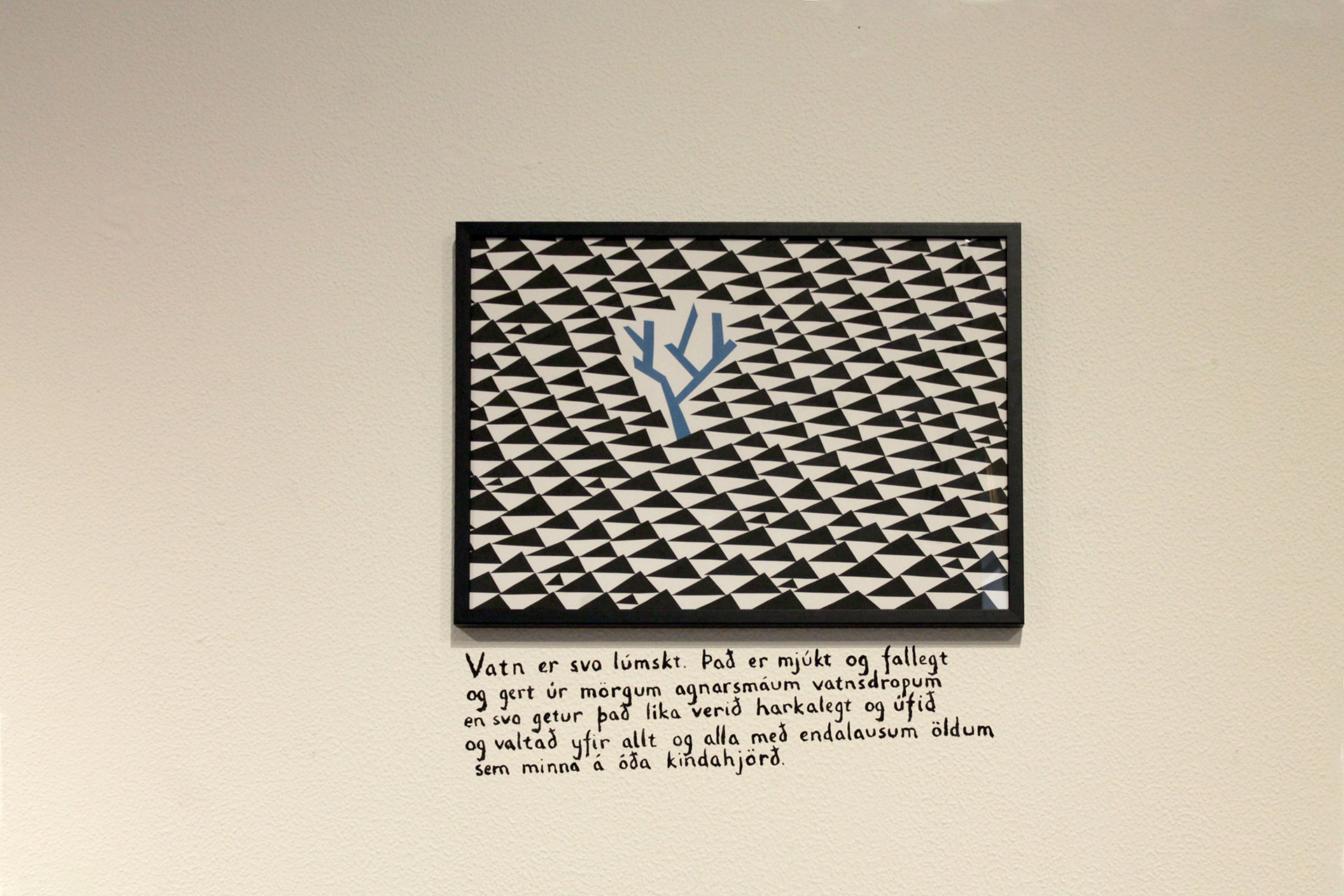

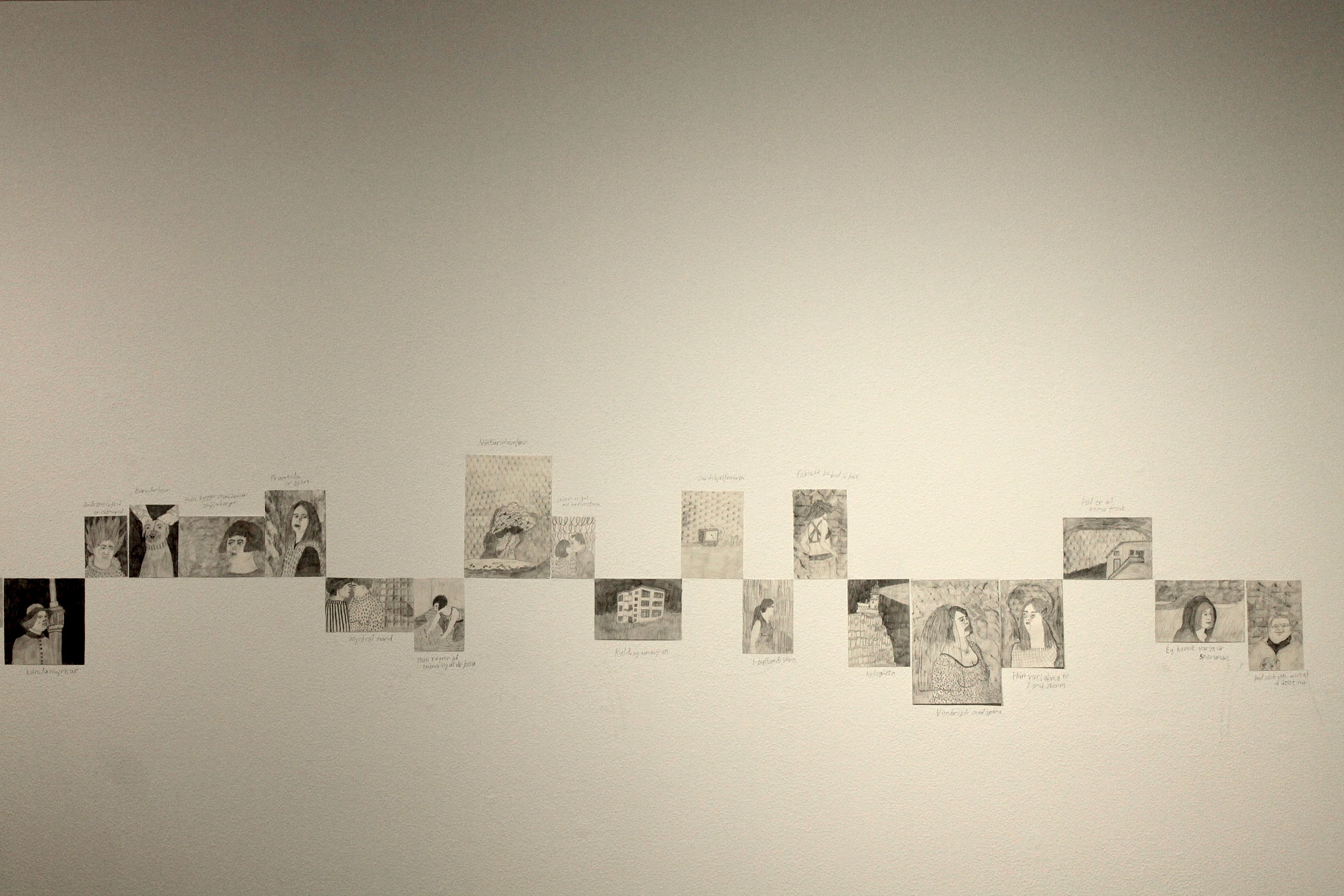

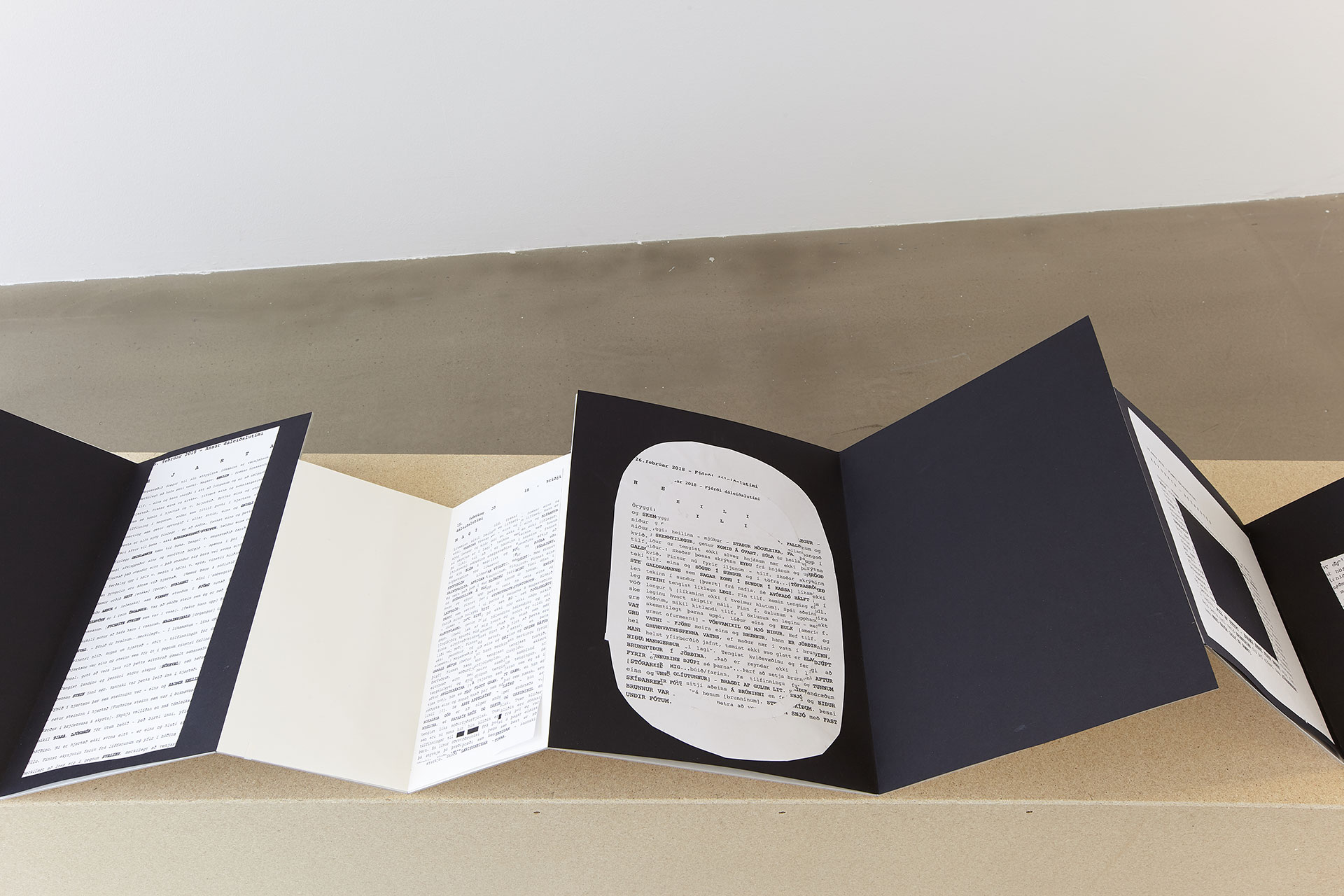

Ragnheiður Getsdóttir, Who created the timeline? (2016) and Meriç Algün, Billboards (2012)

Ragnheiður Getsdóttir, Who created the timeline? (2016) and Meriç Algün, Billboards (2012)

Magnús Sigurðarsson, Requiem for a Whale

Magnús Sigurðarsson, Requiem for a Whale

Childish Gambino, ZEF – This Is France (2018), Falz – This Is Nigeria (2018), Fox – This Is Turkey (2018)

Childish Gambino, ZEF – This Is France (2018), Falz – This Is Nigeria (2018), Fox – This Is Turkey (2018)

Magnús Sigurðarsson, Icelandic Parroty

Magnús Sigurðarsson, Icelandic Parroty

Inclusive Nation aims to open up a discussion about our approach to the otherness. If we look up for the world “nation” in the dictionary we will find “A large body of people united by common descent, history, culture, or language, inhabiting a particular state or territory.”, a definition which underlines the importance of descent, history, culture, all characteristics which can be inherited and can determine a person’s belonging to a certain nation. That definition could, on one hand, sound kind of problematic nowadays when people move abroad so often, and, want it or not, they bring their motherland’s culture with them. On the other hand, exclusiveness is a logical consequence of the existence of borders, countries need to be exclusive in order to define themselves and their population. We ourselves are defined by a process of exclusion: we build our identity by excluding what we are not. The main venue of Cycle, Gerðasafn, hosts the show “Exclusively Inclusive” which, by playing with the words, invites us to reflect about those two important concepts: can we a nation be inclusive while maintaining its identity? If yes, how? At what point exclusiveness becomes racism? And so on.

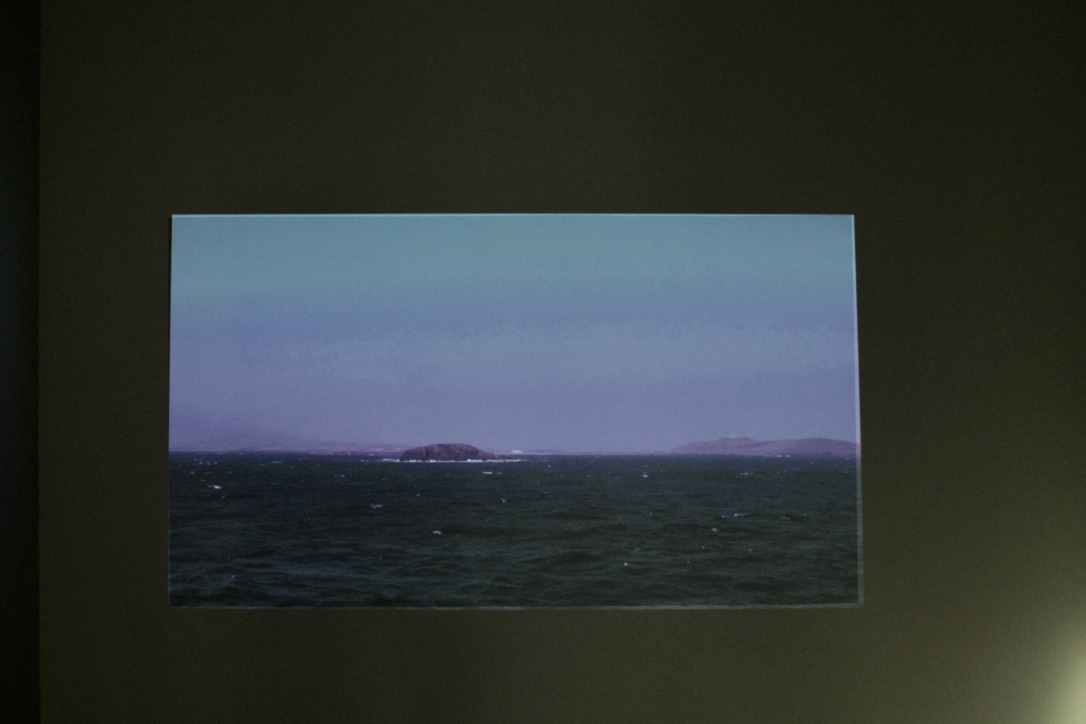

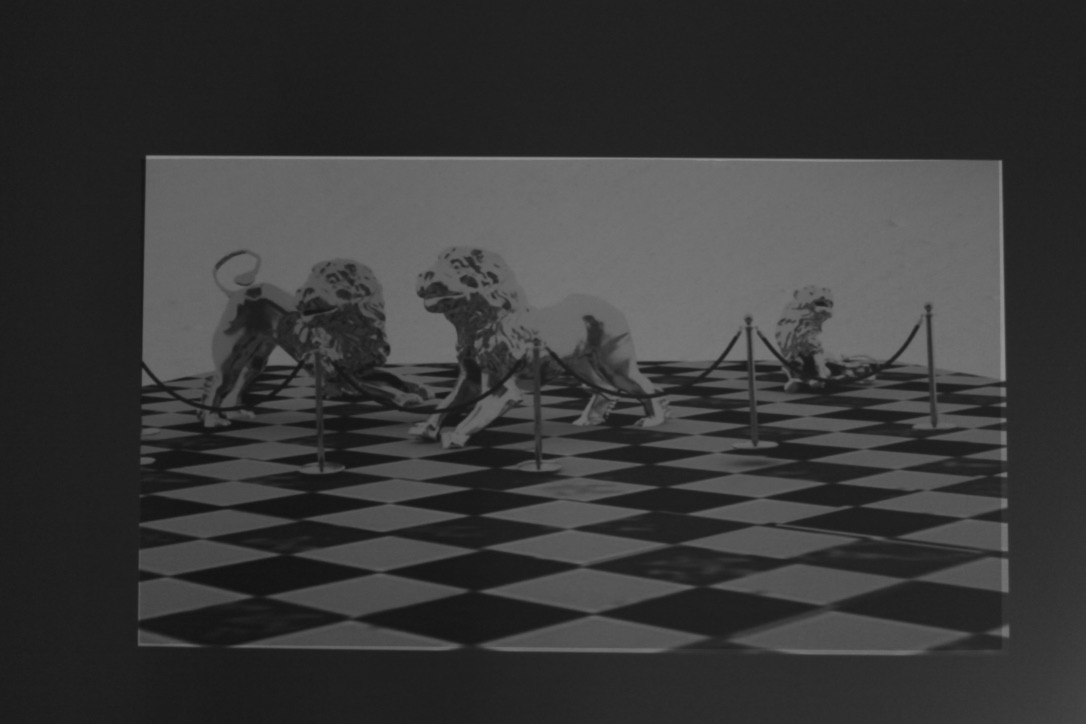

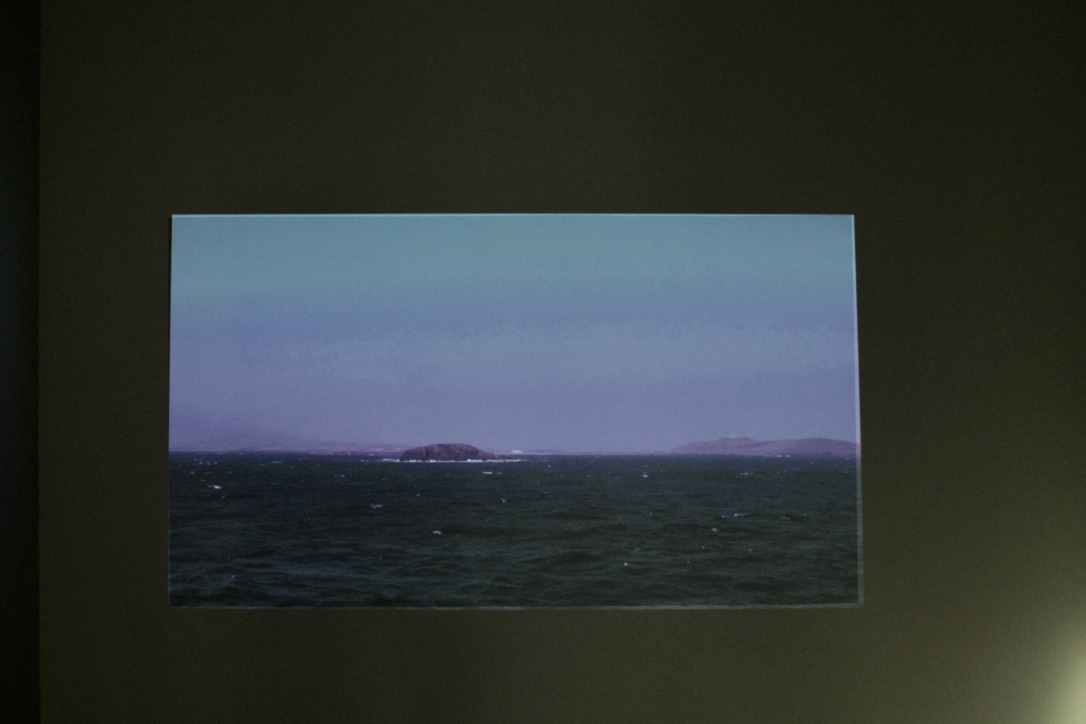

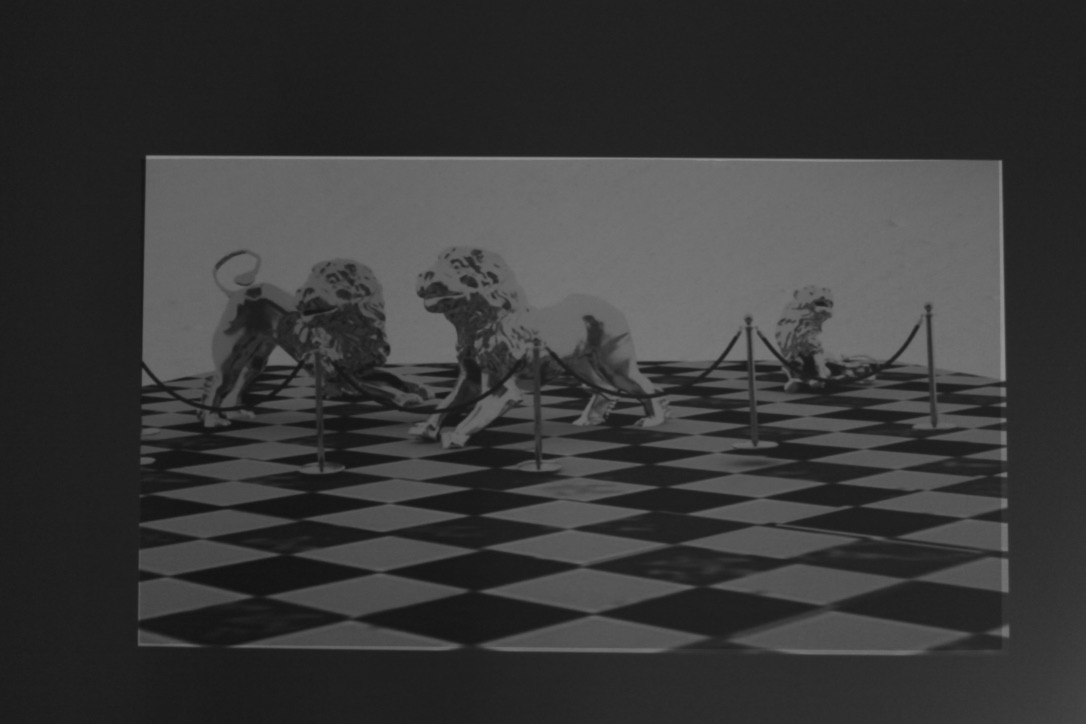

This year Iceland celebrates the centenary of its independence and sovereignty, and its relation with Denmark as well as the impact of its colonial history are taken into account in the festival. The work of Sara Lou Kramer, Norröna Voyage, on show at Gerðasafn, developed from a theory which says that around the 16th century the Danish colonists collected all of the silver goods from Iceland and brought it to Denmark, where they melted the silver and probably used it to make the three lions which are nowadays in the “Knights’ Hall” at Rosenborg Castle. Kramer has been traveling from Denmark to Iceland on the Norröna ferry, she documented her journey and edited the material to make a video of the three silver lions returning back to Iceland and melting again on the Icelandic land.

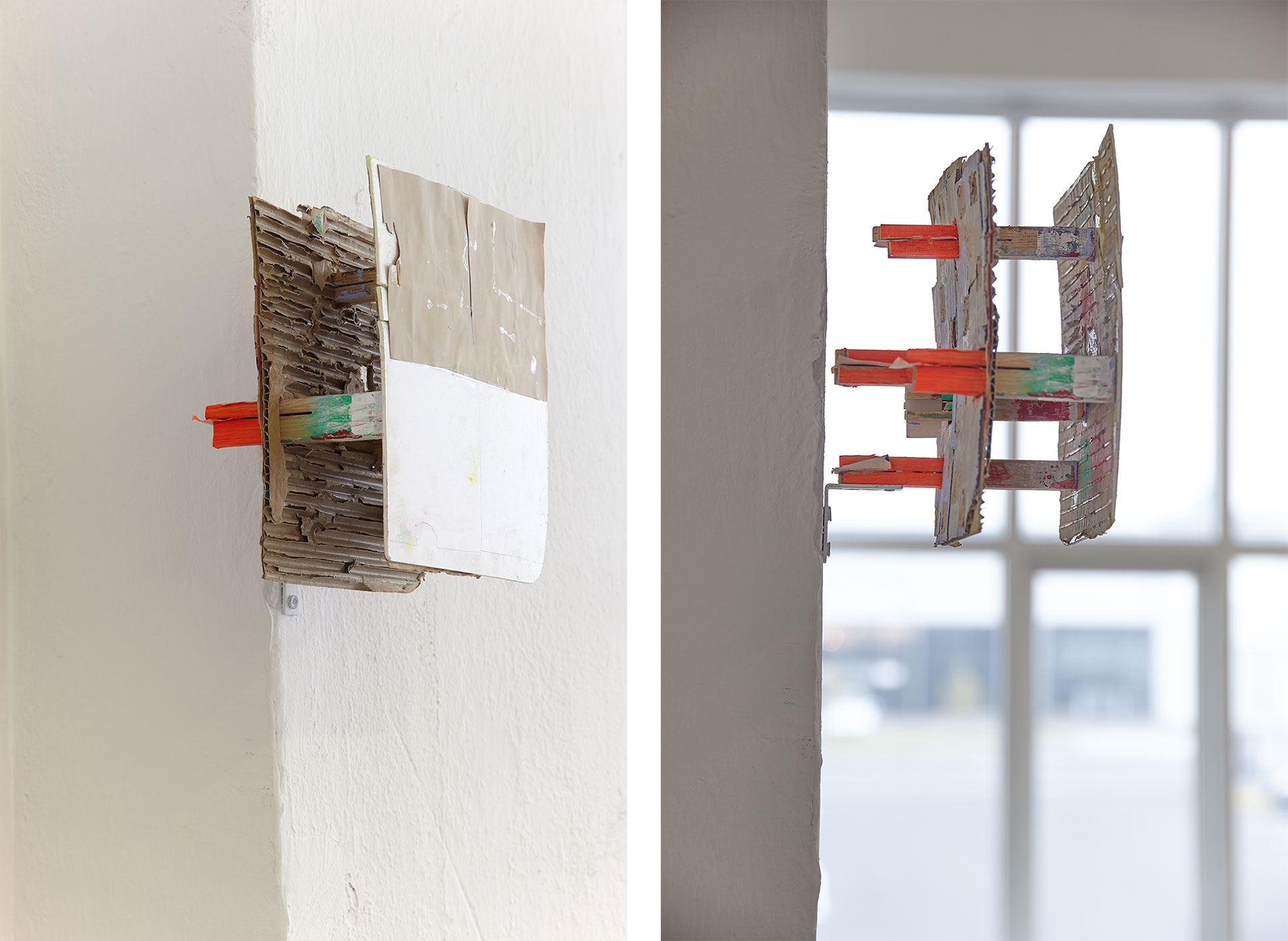

Standing right next to Norröna Voyage, Bryndis Björnsdóttir’s installation De Arm started with an act of reappropriation: the artist picked a splinter off a plantation master’s chair from the Danish West-Indies colonies, which was exhibited in a historical show in Copenhagen. The colonists used to withdraw the sulphur from Iceland to make gunpowder, an extremely important resource to maintain their colonies under control and to conquer more territories, and Björnsdóttir unified these two symbols of the colonial time – the wooden splinter and the sulphur – in a match. A third element closes the conceptual circle of the installation: a rope on the floor. During the opening ropes were ignited just outside of the museum: the performance invites the viewer to reflect on the double usage of gunpowder presented in slow matches, a bivalent element which, on one hand, ensure that the explosion will take place and, on the other hand, guarantees a safe time frame between the ignition and the explosion.

Steinunn Gunnlaugsdóttir’s work The Little MareSausage is an ironic sculpture of a sausage with an elegant fish tail, sitting on a rolled hot-dog bread. The piece is placed in the Tjörnin pond, and it has been broadly discussed, dividing the inhabitants of the capital in two groups: those who love it and those who criticise its phallic shape. The statue is a sort of new creature which merges the Danish iconic The Little Mermaid sculpture and one of the more famous Icelandic dish: the hot-dog. The work provokes in the viewer reflections about the particular connections arising from coloniser-colonised relationships, cultural exchanges, appropriations, revisitations and new developments are unavoidable, interactions which influence the identities of the involved nations and individuals, determining cultural contaminations which will soften the borders between the countries. But if the Icelandic history and culture is tied to the Danish one, does this make Icelanders a bit Danish and Danish a bit Icelanders? After all, a nation is “A large body of people united by common descent, history, culture […] ”

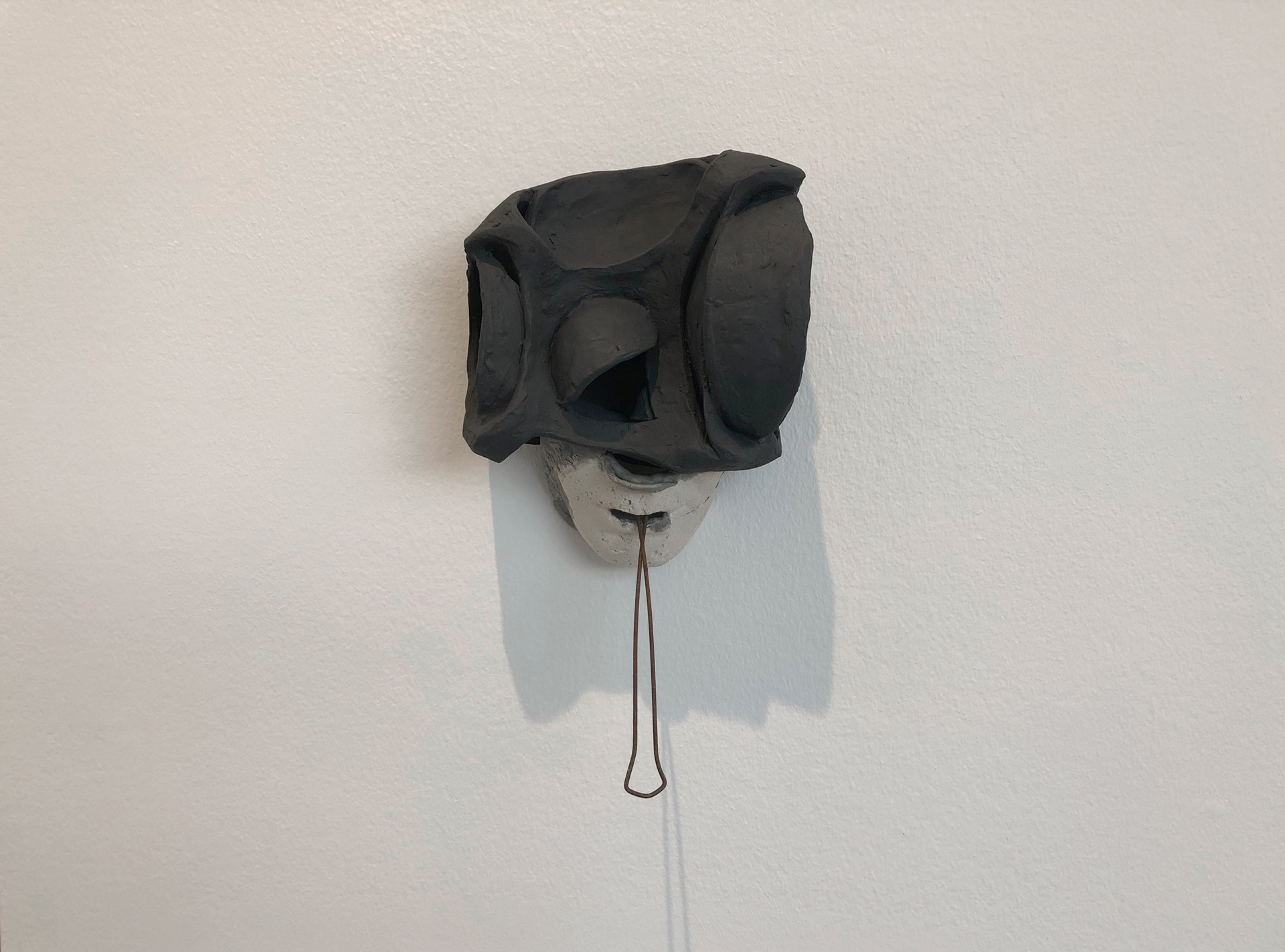

Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018)

Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018)

Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018)

Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018)

Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018)

Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018)

Sara Lou Kramer, Norröna Voyage

Sara Lou Kramer, Norröna Voyage

Sara Lou Kramer, Norröna Voyage

Sara Lou Kramer, Norröna Voyage

Steinunn Gunnlaugsdóttir, The Little MareSausage (2018)

Steinunn Gunnlaugsdóttir, The Little MareSausage (2018)

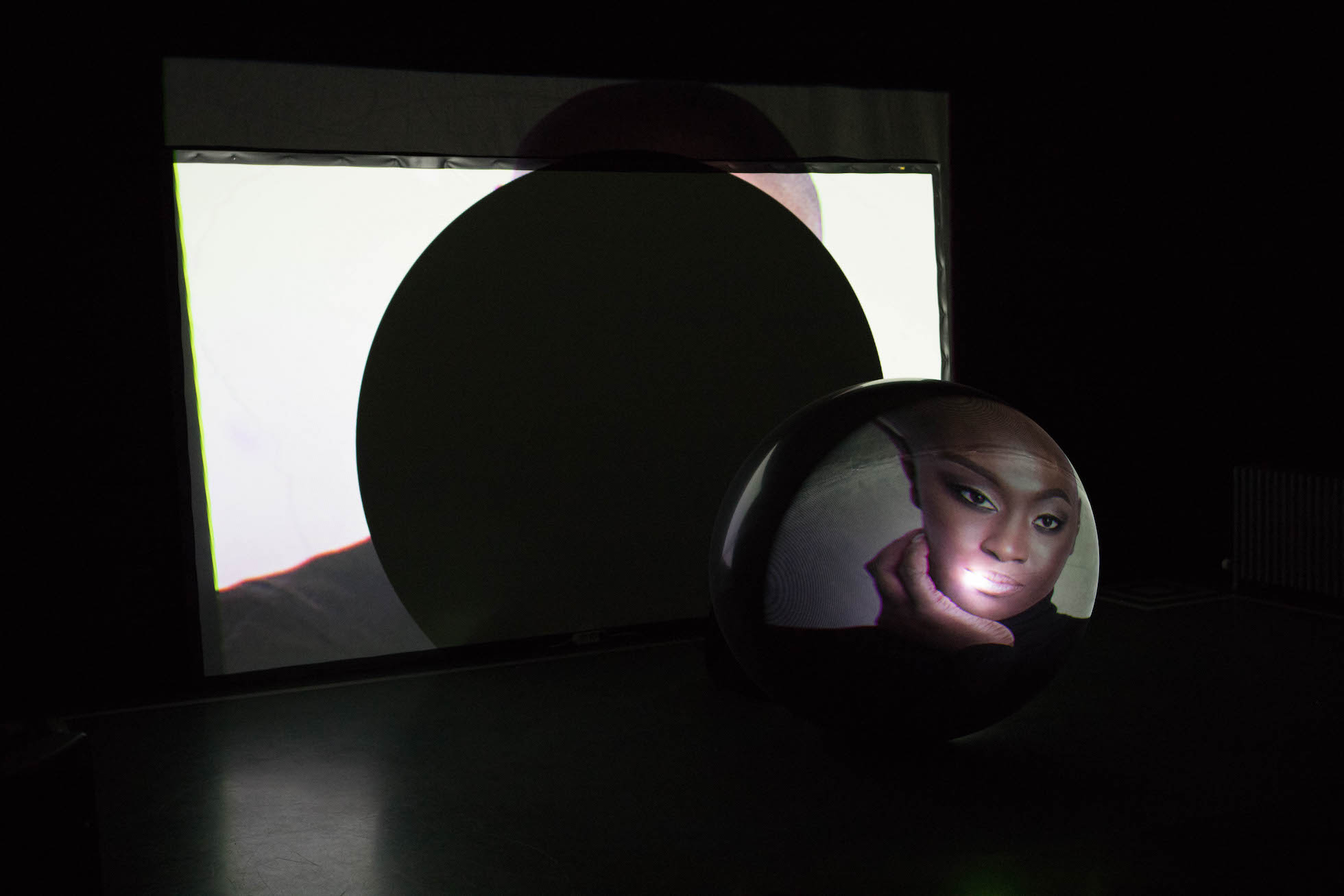

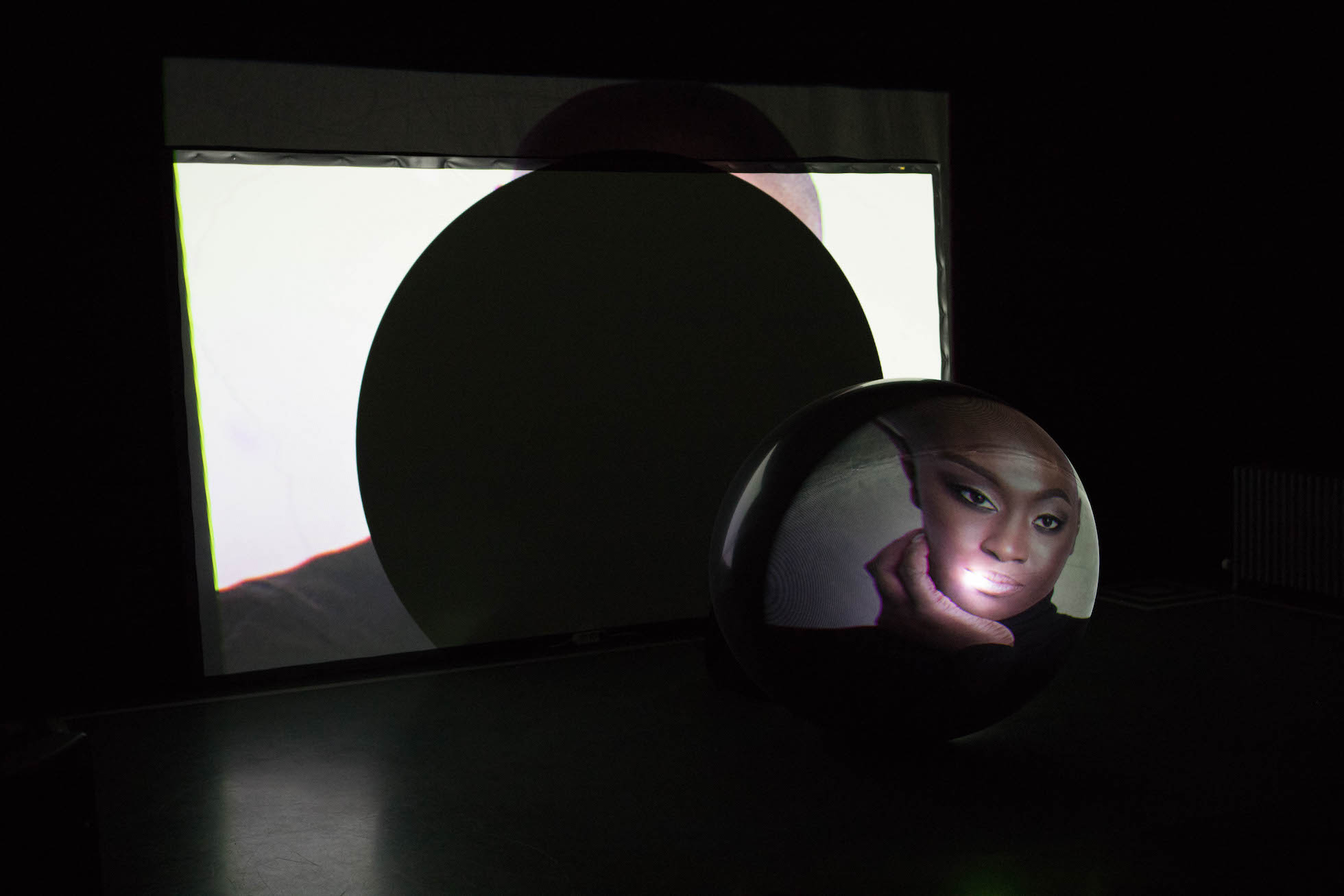

Jeannette Ehlers, Black Matter

Jeannette Ehlers, Black Matter

Jeannette Ehlers, Black Matter

Jeannette Ehlers, Black Matter

The definition of “nation” given by the dictionary mentions also the role of language in delimiting a culture, and in fact the first problem the team of Cycle (the curator Jonatan Habib Engqvist, the artistic director Gudný Gudmundsdóttir, the co-artistic director Tinna Thorsteinsdóttir and the co-curator and researcher Sara S. Öldudóttir) had to face was the lack of an Icelandic word corresponding to “inclusive”, so that in Icelandic the festival is called Þjóð meðal þjóða (A nation among nations). This led them to reflect upon the role of language in terms of defining the nature of a country and of enlighting peculiarities of a given culture. Ludwing Wittgenstein states in the Philosophical Investigation that the meaning of a word lays in the use of the word itself, and in order to grasp its meaning in any given context we need to look at the non-linguistic activities in which a given group of people engages. These activities plus the specific use of language of the community create a “form of life”. Our understanding of the world is therefore shaped by our language, since it is the means by which we represent the information we get from our experiences. Language became a sort of red thread in this edition of the festival, because of its qualities of being both the consequence of the development of a culture and, in some way, the cause of a population’s understanding of the world.

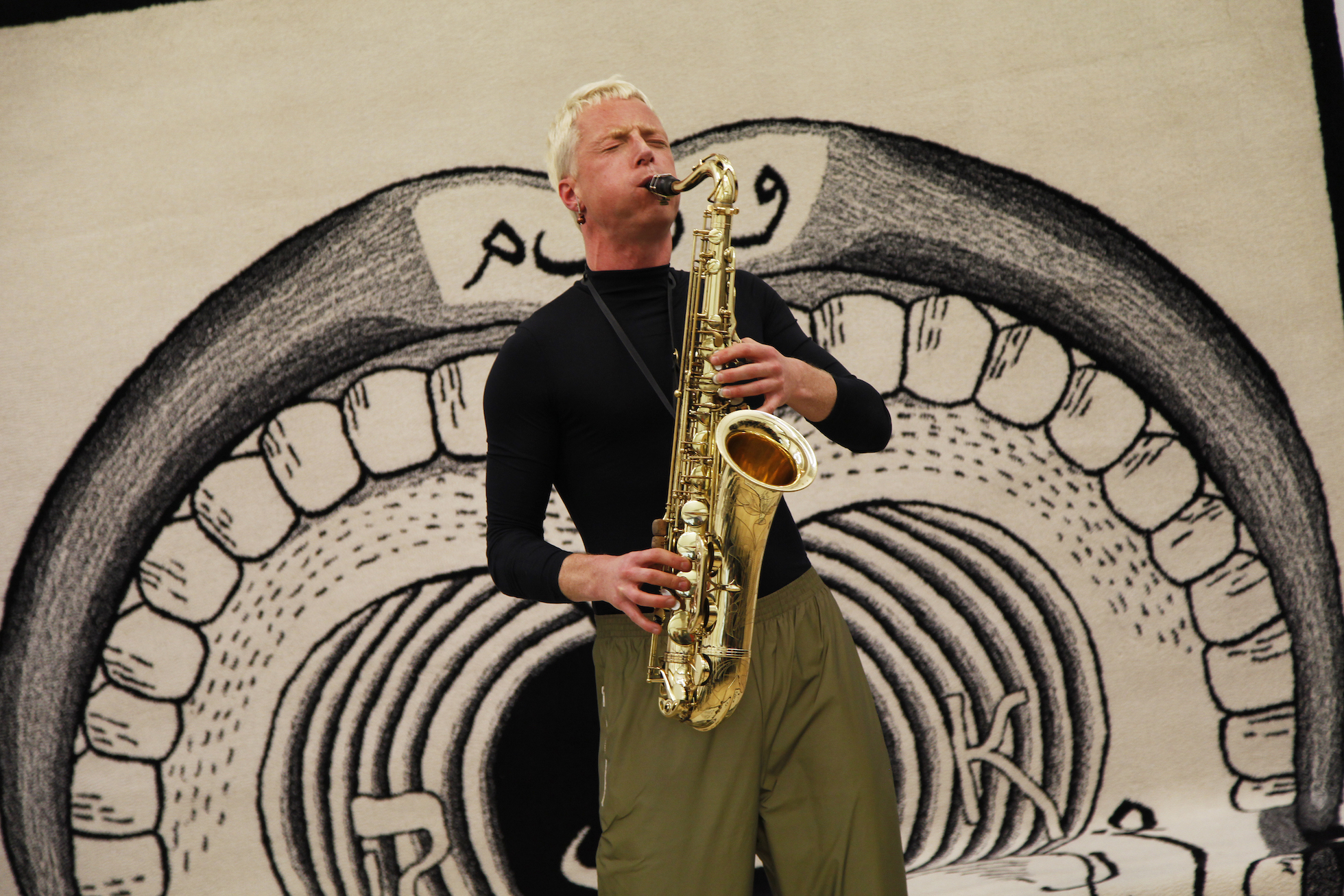

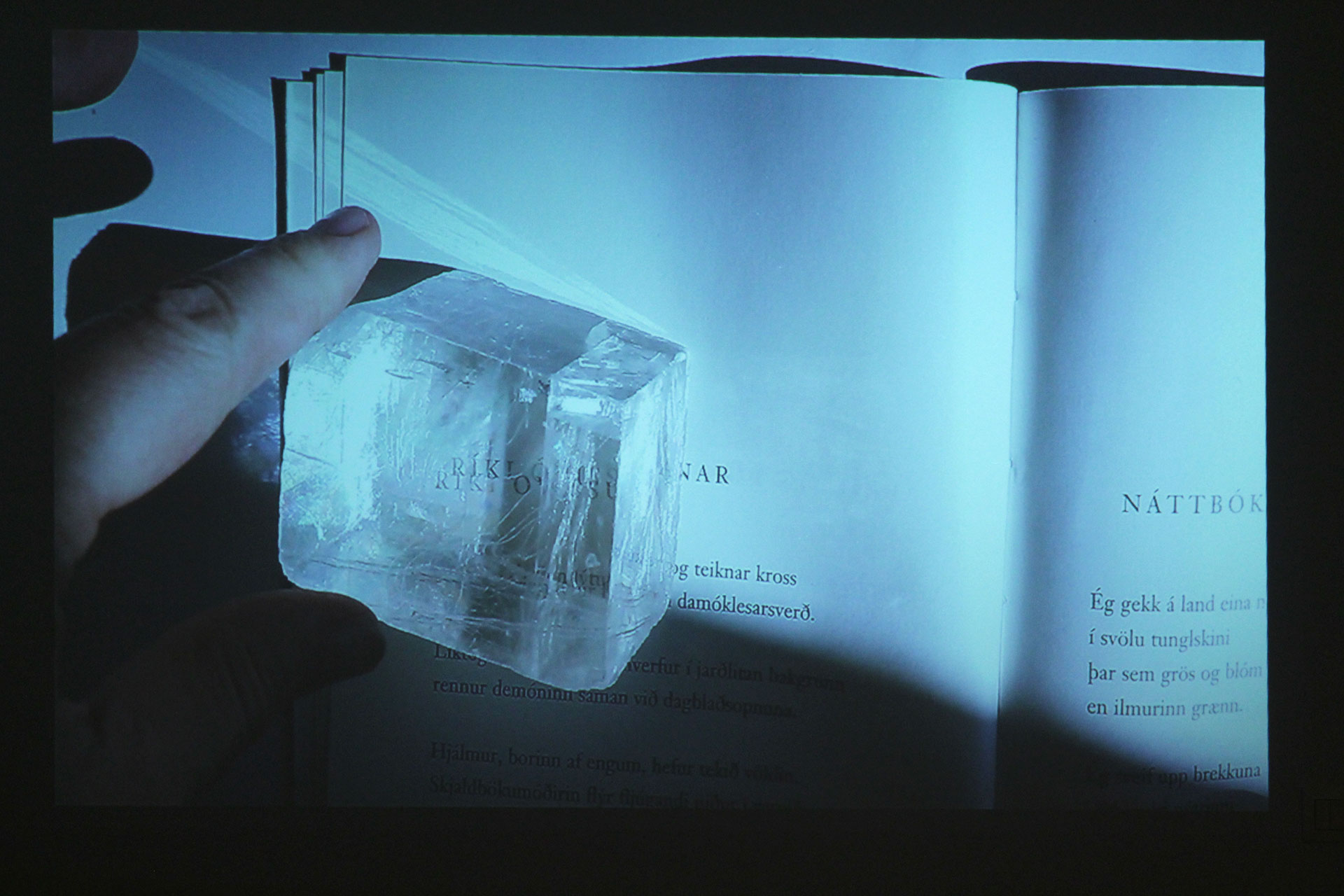

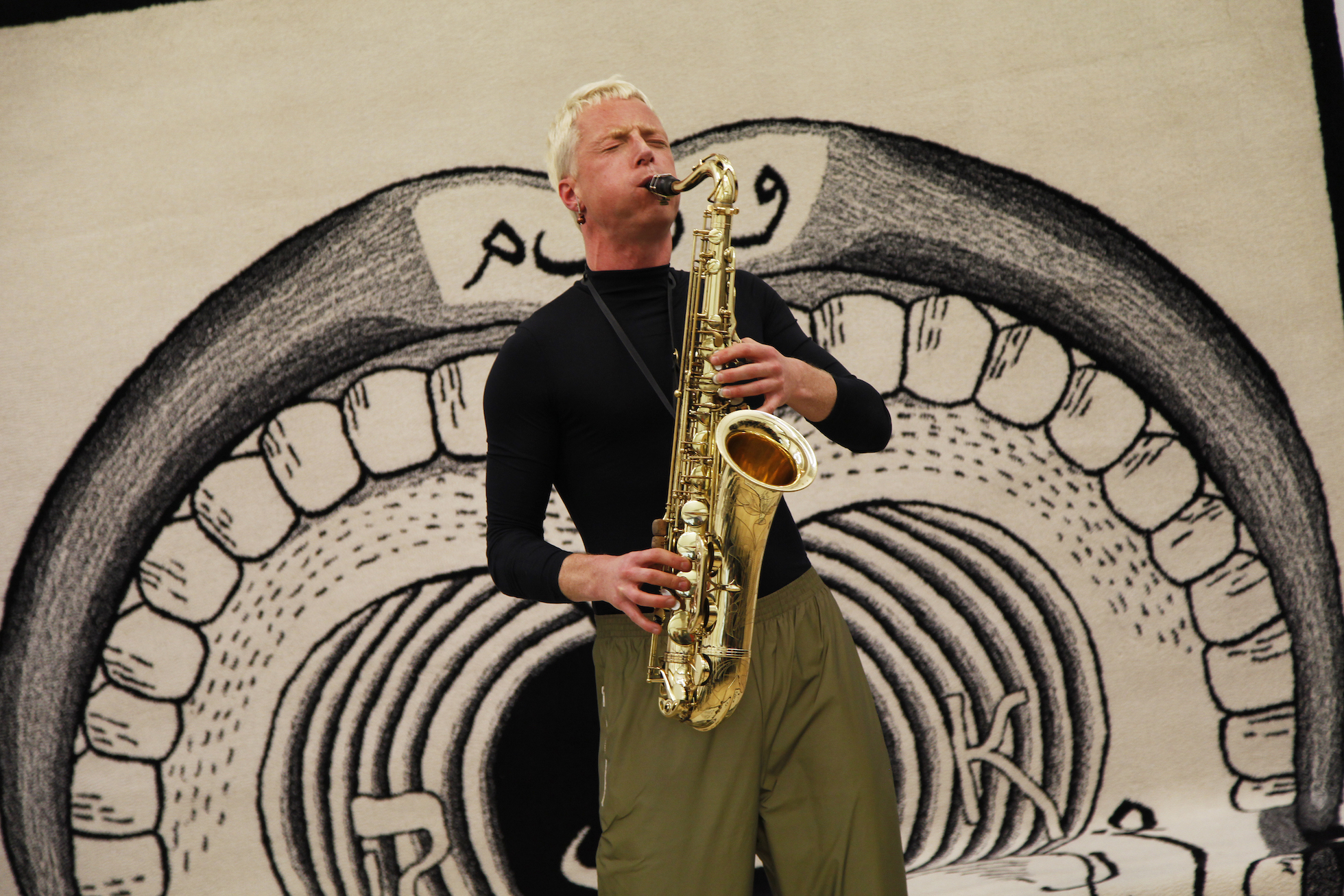

The piece Mother Tongues and Father Throats by the art collective Slavs and Tatars, which is part of the show Exclusively Inclusive, reflects on the “khhhhhhh” sound that is used in many Arabic languages but does not exist in most of the Northern European ones. The work presents a diagram of the mouth where different letters from Middle East alphabets are placed to indicate which part of the mouth is used to pronounce them. The piece is also a tapestry, it hang to the wall and it goes down to the floor forming a sort of soft bench for the viewers to sit and rest. The “khhhhhhh” is usually perceived as an abstruse sound from non-Arabic people, it sounds primitive and strange as it’s not completely understood, but the piece combines this sound with a space for people to relax and to feel comfortable in, attempting to modify the perception of that sound and of linguistic in general, which is usually seen as a tough subject to the exclusive competence of academics. During the opening of the Cycle Bendik Giske performed playing his saxophone while walking around the exhibition. He goes beyond the classical way of playing the instrument by incorporating sounds of the mechanics and his own breath. At some point he stood on the work Mother Tongues and Gather Throats and created an interesting and intense interaction between the particular way he uses his mouth and his throat to produce a wide range of sounds and the mouth and throat diagram behind him.

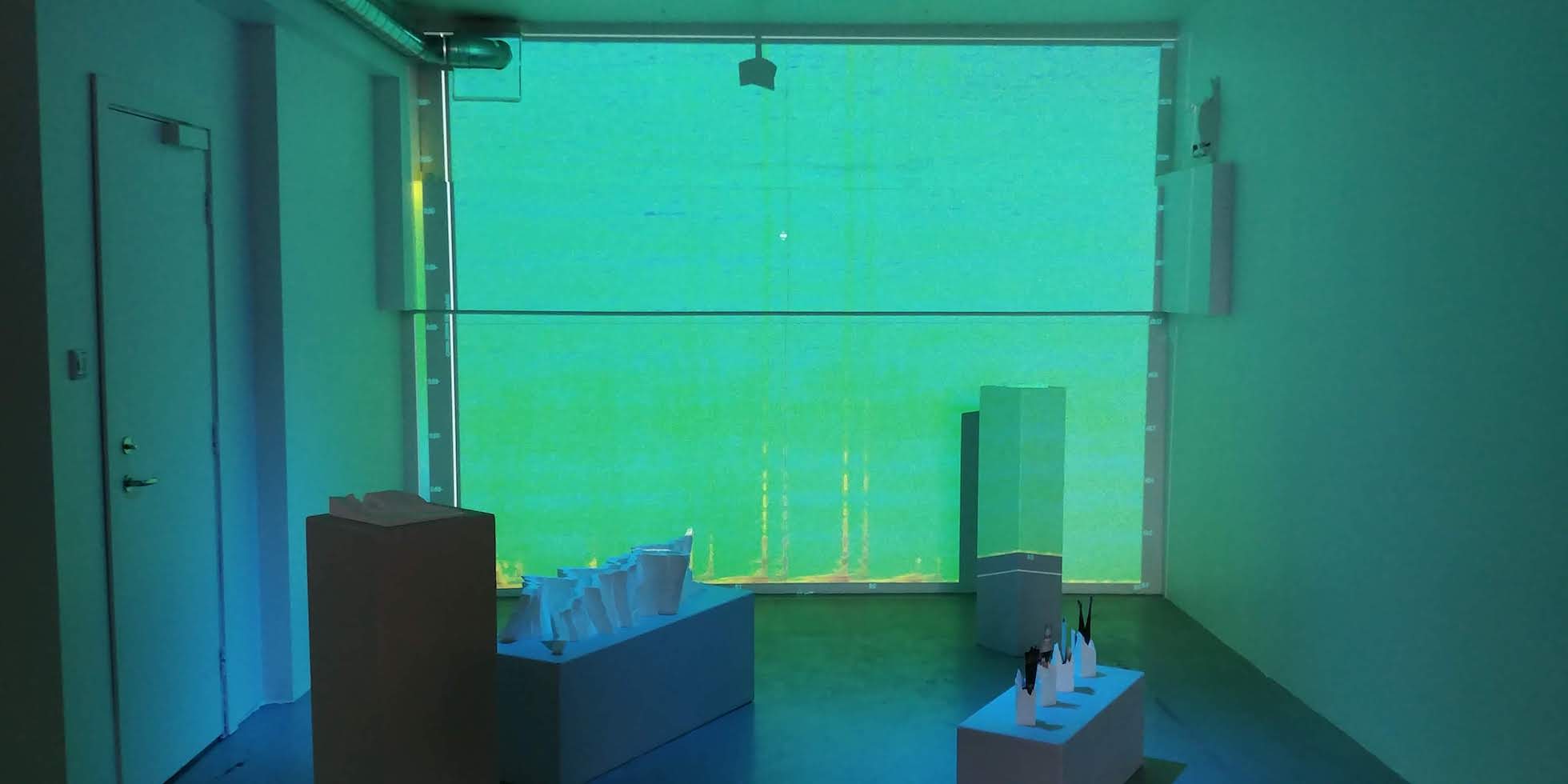

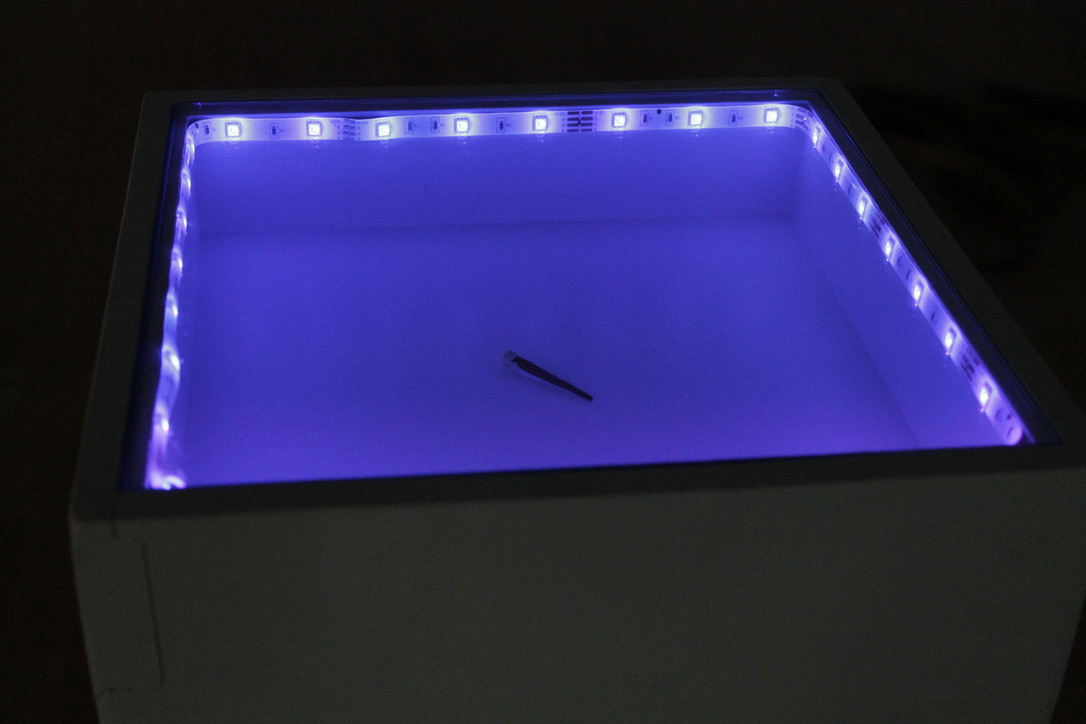

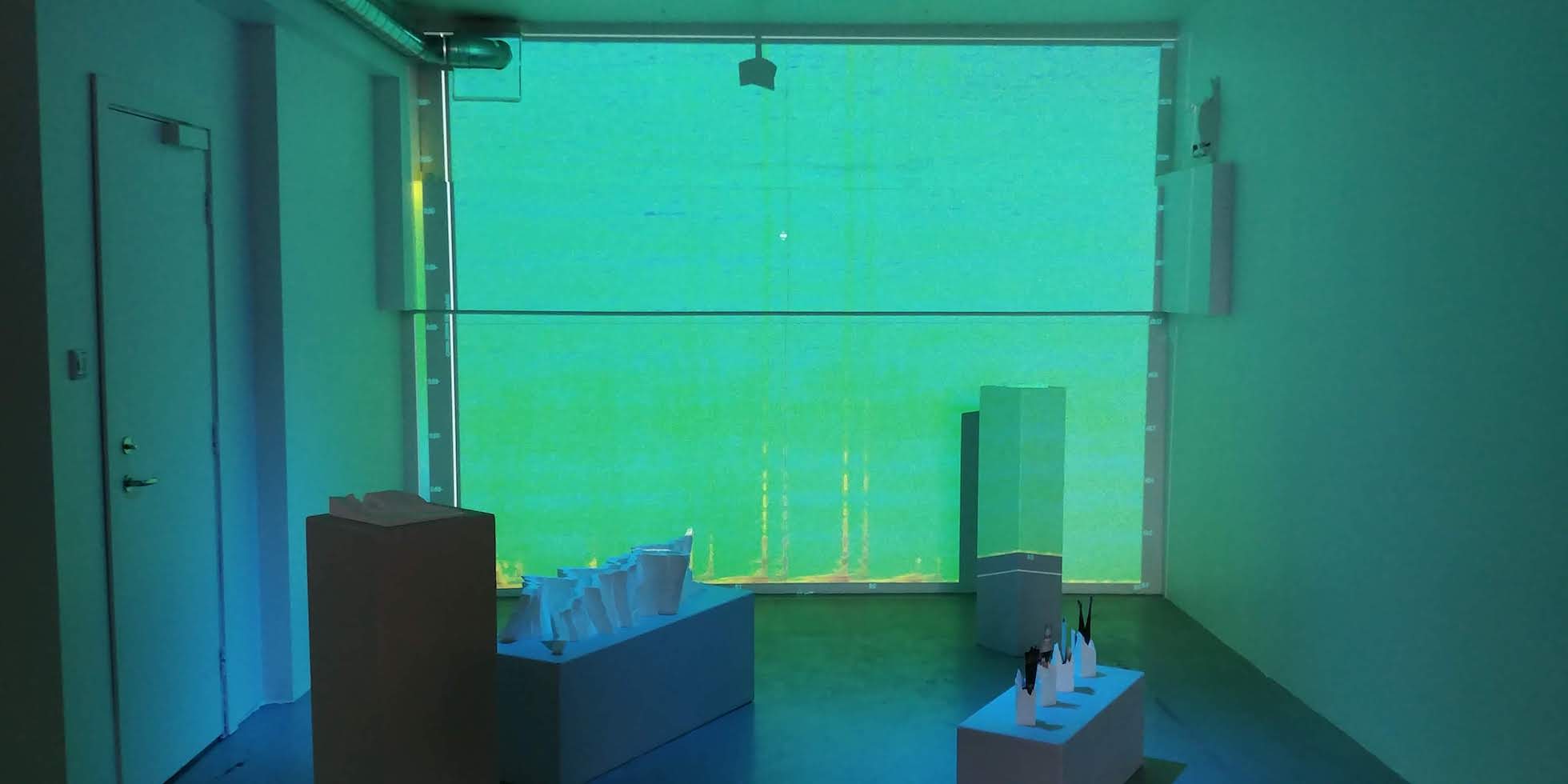

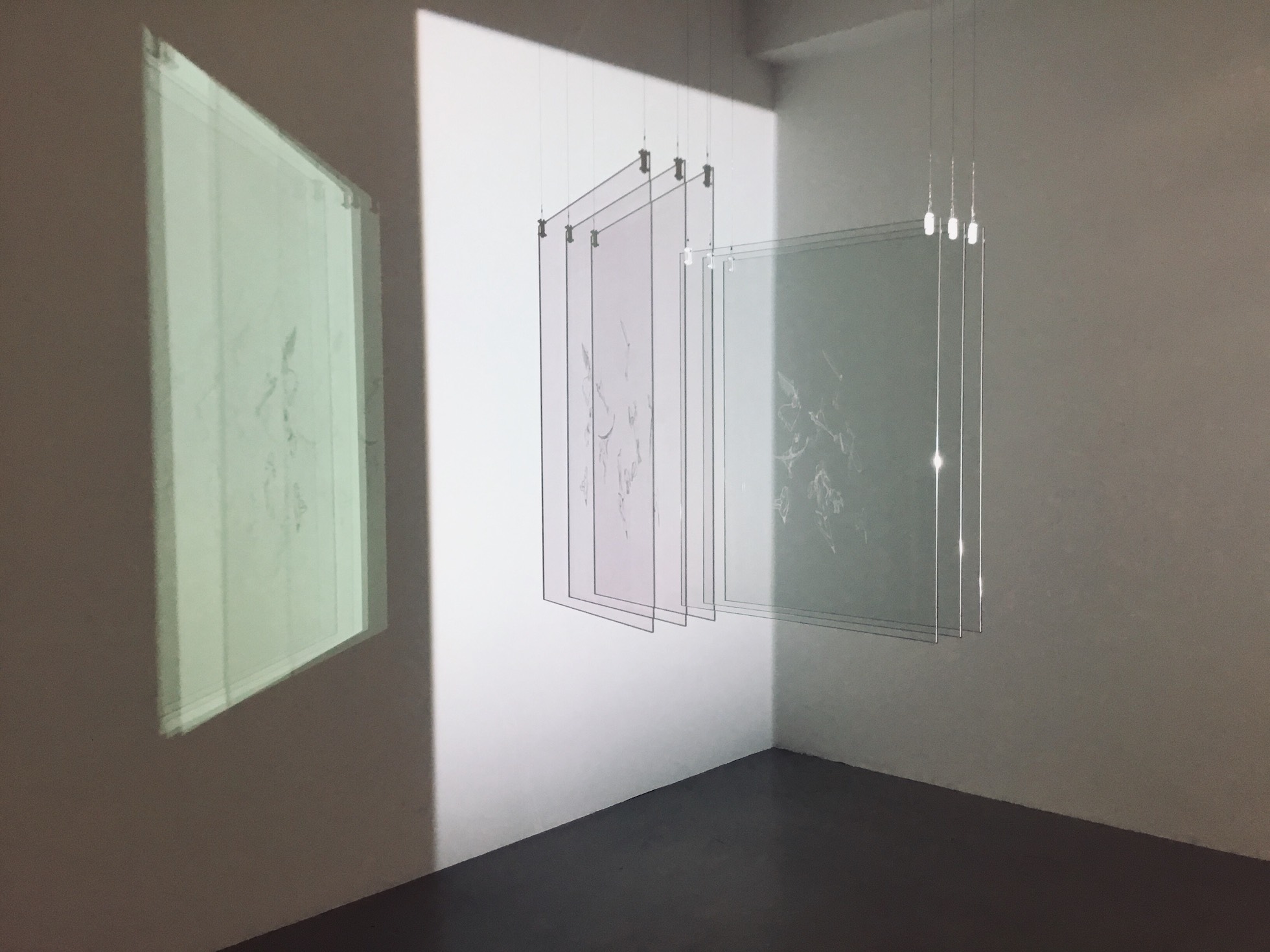

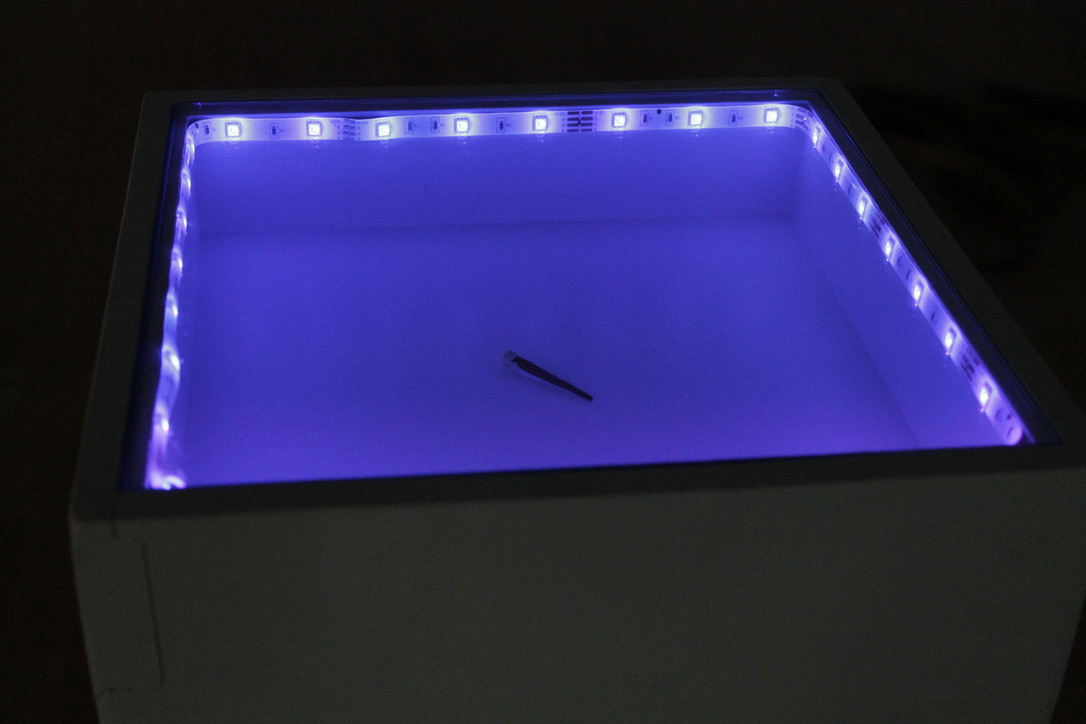

Jeannette Castioni & Þuríður Jónsdóttir have collaborated on the work “Sounds of Doubt”, a piece which investigates the possible connections between the sounds of a certain language/country and the local culture, asking through their work if such a connection exists. A microphone placed in the room detects the sounds from the surroundings and passes the information to a projector which creates a visualisation of the sounds we produce, while models of the seabed surrounding Iceland are scattered in the space. One of these models in particular has been made by merging the submerged peaks and the sound waves of the Icelandic national anthem, showing the similarities of their profiles and shapes. A video work presents the culmination of a process started during Cycle 2017 when through Sounds of Doubts – Workshop groups of artists worked with participants from different Nordic Countries. The aim was to unveil the influences of natural and cultural environments on the participants’ behaviour. The video shows alternately an interview with two Greenlandic ladies, holding inflatable balls depicting the planets of the solar system, and recordings from starships traveling through the universe. Sounds of Doubts creates a parallelism between our existence in the world as highly evolved creatures, with our cultural and knowledge luggage, and the universe invisible structures, primordial forces moving by nature’s laws which constitutes the starting point of it all. There is a flux of life which unifies everything existing in the universe, which we can’t avoid because we are part of a wholeness. We tend to forget where we come from, blinded by idea that we are some kind of superior beings just because we can build tools and we have technologies, but we just assemble or transform preexisting items. As Aristotle’s theory of act and potency says, every substance existing in nature has already the potentiality to become the actual objects in which they develop / are developed by the human beings. We are, indeed “[…] such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.”, and here is where inclusiveness becomes a matter of accepting and embracing the wholeness we are part of.

Jeannette Castioni & Þuríður Jónsdóttir have been working together as an artist and a musician, bringing together different experiences and points of view to create a multi-sensorial work which communicates through different media and through different languages. Cycle, in fact, embraces the idea of language in a comprehensive way, languages are not just about spoken or written communication, they are also about the individual’s different ways of expression: the festival brings together visual art, music, design, poetry and even architecture, artists are encouraged to maintain the characteristics of their own art, but also to open conversations and to work across the borders of nations and arts.

Slavs and Tatars, Mother Tongues & Father Throats (2012)

Slavs and Tatars, Mother Tongues & Father Throats (2012)

Bendik Giske

Jeannette Castioni & Þuríður Jónsdóttir, Sounds of Doubts, (2017 – 2018)

Jeannette Castioni & Þuríður Jónsdóttir, Sounds of Doubts (2017 – 2018)

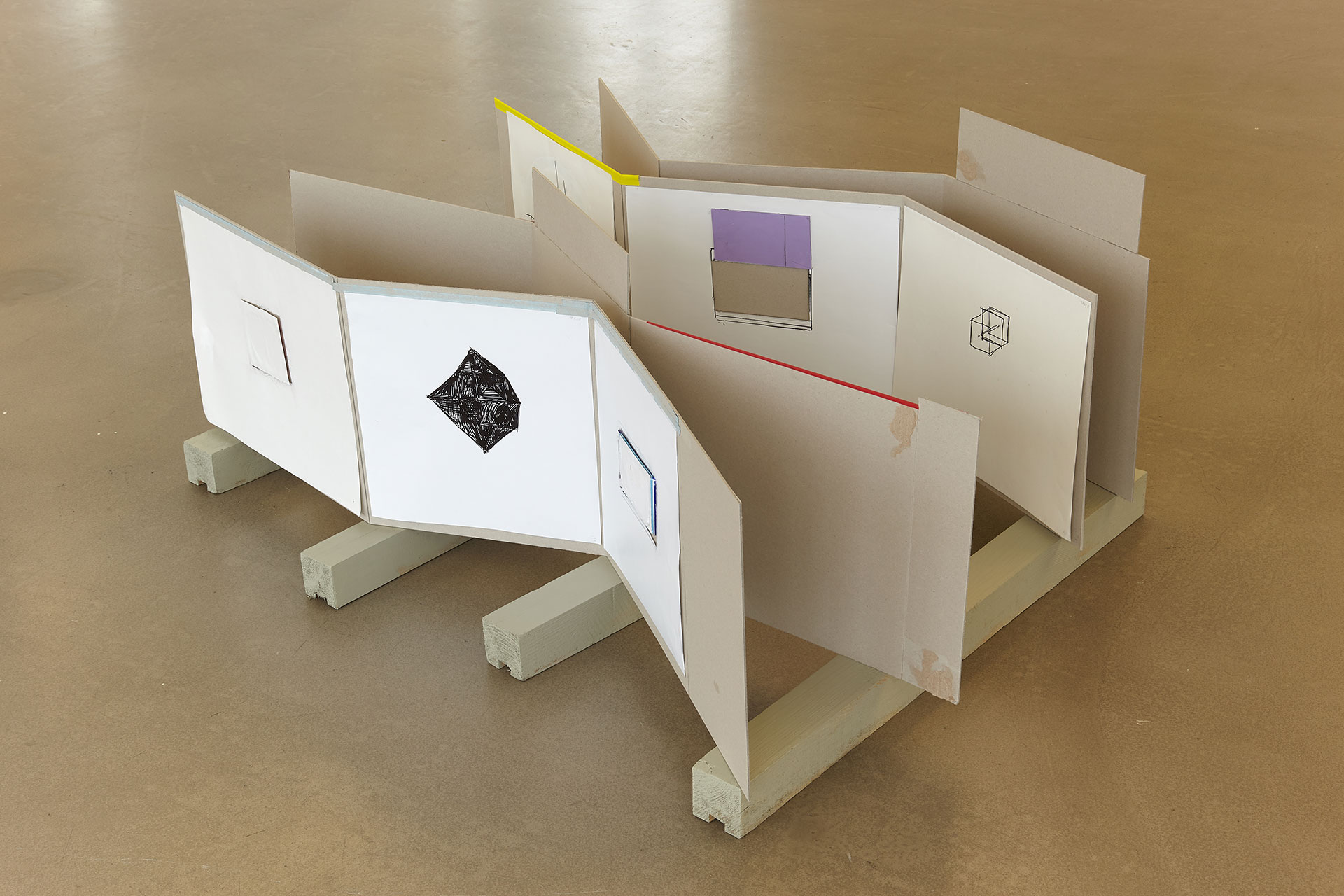

Exclusively Inclusive, installation view

Exclusively Inclusive, installation view

The Circle Flute

Libia Castro and Ólafur Ólafsson, In Search of Magic

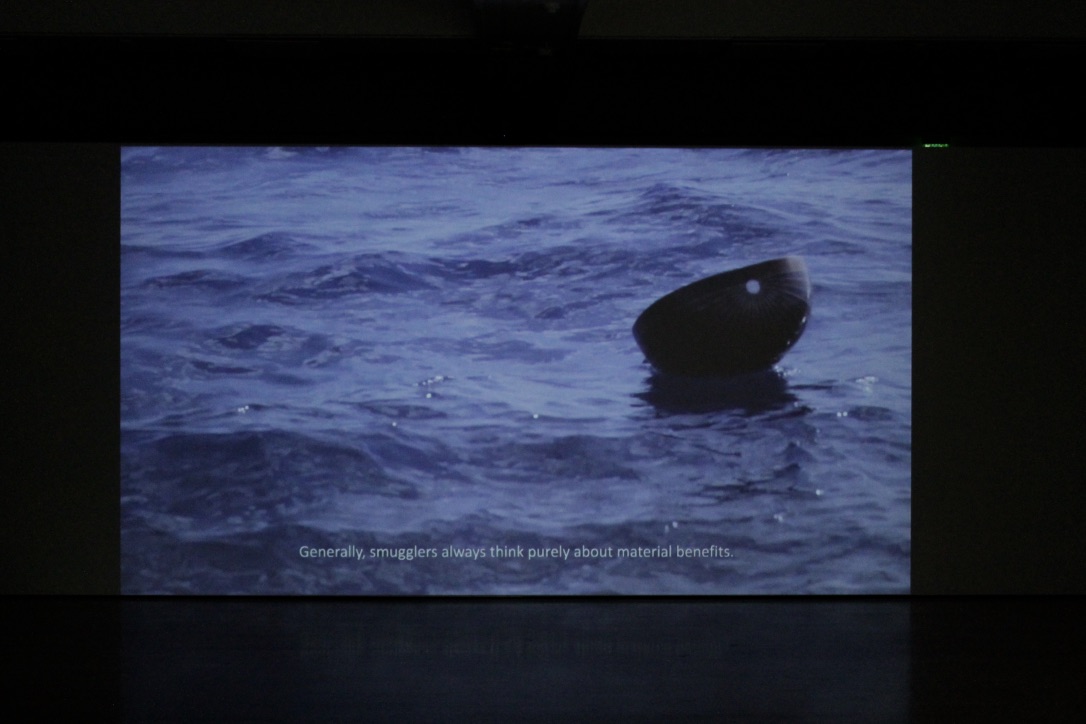

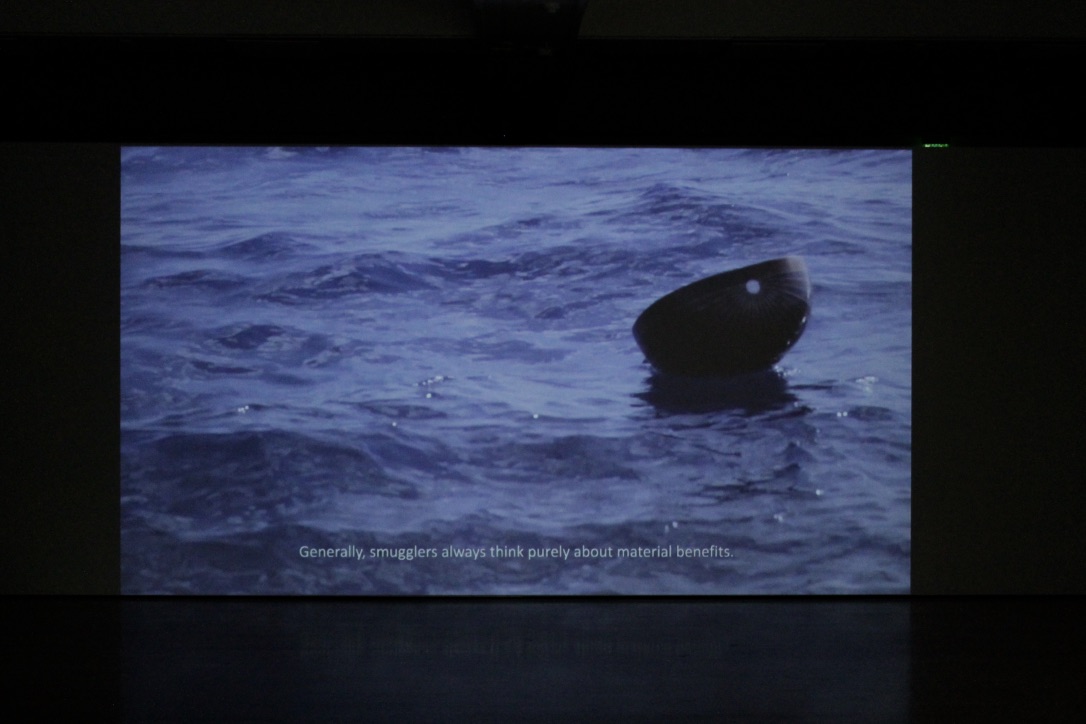

Pinar Öğrenci, A Gentle Breeze Passed Over Us (2017)

The Circle Flute is the perfect example of a borderline object placed on the edge between art and design. It has been designed by Brynjar Sigurðarsson and Veronika Sedlmair to explore and expand the possibilities of a normal flute: the instrument combines four flutes to form a one big and circular instrument which needs four people to be played and it’s able to produce a wider interaction of sounds than a simple flute. The work opens up to a collaborative use of the object, four people need to coordinate their movements and their actions since the Circle Flute is a combination of four curved flutes attached to form a single instrument. The Circle Flute is thought to be played for one listener who is supposed to stay in the middle of the instrument to get an immersive experience of the music, embraced by the flute and its sounds.

Libia Castro and Ólafur Ólafsson’s contribution to the festival fits into this process of unification of different forms of art. They started the project In Search for Magic in May 2017 with a group of musicians and composers, bringing together people with different approaches to music to compose songs on the Proposal for a new Constitution for the Republic of Iceland written in 2011 which was approved by the Icelandic population through a referendum in 2012 but hasn’t been approved by the parliament yet. The idea behind the constitution is to give voice to the people, the constitution has in fact been created through a collaborative project, people would bring new ideas and would discuss them together, everyone was welcome to contribute to the drafting of the constitution. In Search for Magic moves toward the same direction, the project is rooted in a collaborative effort which engages with the public, in fact viewers were invited to take a look at the workshop when musicians and composers were working, and to actually take part in the work by reading a sentence from the constitution which was recorded and will be edited in a single recording which will literally unify the individuals’ voices. The project embodies the utopia of a different world in which people take actively part in the building of their future, and the borders between artists and non-artists are torn down.

The artworks presented in the show Exclusively Inclusive and in the public spaces stay true to their nature of artworks even when the subject is placed in a social/political context. The video work by Pınar Öğrenci, A Gentle Breeze Passed Over Us, reflects about the terrible journey people from the Middle East have to go through to reach Europe’s lands, the piece is based on the story of a professional musicians from Iraq who was forced by human traffickers to leave behind his oud in order to fit more people in the ship. Despite the strong thematic, the video treats the episode in a highly delicate way, it does not show violence, but it communicates through poetic and emotional images, addressing the story to our humanity. Art doesn’t need to become a cold documentary about political and social situation in the world, there are many ways to tell stories, and art needs to keep its own touch.

Manifesta 12 in Palermo has been dealing with similar issues, but the biennial consists of mostly video works documenting the immigrants’ life in Italy or their original culture, a format which tends to repeat itself and does not fit such a big exhibition. Moreover, the works are often reduced at pure documentation, the glimpse of art and creativity is hidden somewhere behind technology, the message keeps repeating itself in each video, progressively losing its emotional impact on the viewers. Exclusively inclusive, instead, takes the opposite approach: the selected works do deal with tough themes, but the re-elaboration of the material made from the artists, the multiple collaborations which bring to multimedia outcomes, the way artists address their works to different senses to get the viewer/listener/smeller totally involved, all these qualities manage to give a new conformation to those images to which we are so inured, a comprehensive experience which talks to us on a new level.

Ana Victoria Bruno

Photo credits: Ana Victoria Bruno, Anita Björk, Leifur Wilberg

Website: www.cycle.is

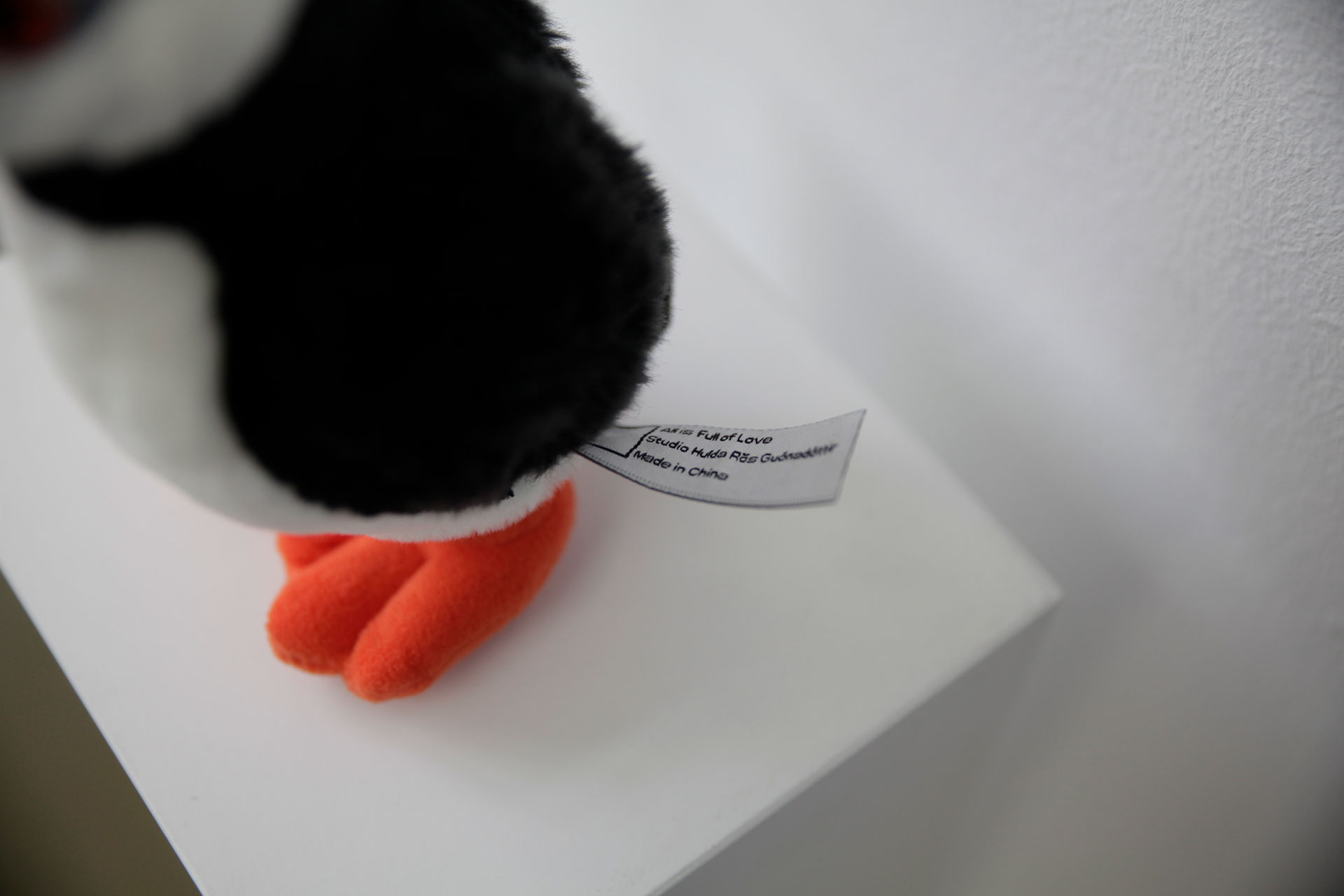

All is full of Love – Studio Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir. Curtesy of the artist

All is full of Love – Studio Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir. Curtesy of the artist From the studio. Photo: Craniv Boyd

From the studio. Photo: Craniv Boyd

Melania Ubaldo, Er einhver íslendingur að vinna hér? (2018)

Melania Ubaldo, Er einhver íslendingur að vinna hér? (2018)

Ragnheiður Getsdóttir, Who created the timeline? (2016) and Meriç Algün, Billboards (2012)

Ragnheiður Getsdóttir, Who created the timeline? (2016) and Meriç Algün, Billboards (2012) Magnús Sigurðarsson, Requiem for a Whale

Magnús Sigurðarsson, Requiem for a Whale Childish Gambino, ZEF – This Is France (2018), Falz – This Is Nigeria (2018), Fox – This Is Turkey (2018)

Childish Gambino, ZEF – This Is France (2018), Falz – This Is Nigeria (2018), Fox – This Is Turkey (2018) Magnús Sigurðarsson, Icelandic Parroty

Magnús Sigurðarsson, Icelandic Parroty Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018)

Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018) Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018)

Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018) Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018)

Bryndís Björnsdóttir, De Arm (2018) Sara Lou Kramer, Norröna Voyage

Sara Lou Kramer, Norröna Voyage Sara Lou Kramer, Norröna Voyage

Sara Lou Kramer, Norröna Voyage Steinunn Gunnlaugsdóttir, The Little MareSausage (2018)

Steinunn Gunnlaugsdóttir, The Little MareSausage (2018) Jeannette Ehlers, Black Matter

Jeannette Ehlers, Black Matter Jeannette Ehlers, Black Matter

Jeannette Ehlers, Black Matter Slavs and Tatars, Mother Tongues & Father Throats (2012)

Slavs and Tatars, Mother Tongues & Father Throats (2012)