Ólafur Elíasson Opens a Retrospective at the Tate Modern, Activates a Participatory Togetherness

Ólafur Elíasson Opens a Retrospective at the Tate Modern, Activates a Participatory Togetherness

Ólafur Elíasson’s In Real Life at the Tate Modern presents a deeply moving collection of work that encompasses a full range of emotion, medium and perception into one intensely thought proving experience. Nodding to Elíasson’s 2003 The Weather Project at the Tate, In Real Life combines a sensory interaction of people, experience, time, and space. The exhibition is totally and fully immersive, both inside and beyond the exhibition walls. Historically, Elíasson’s practice has revealed a deep and curious examination of light and environment in both an intricately scientific exploration and a delicately artistic unpacking, and In Real Life pays homage to just how massively prolific his career has been. Elíasson’s works prompt us to examine how we think about nature and perception, encouraging us to navigate our environments in new, playful ways. In a moment of temporary interaction, viewers become one in intimate experience, uniquely together. Around forty works spanning over three decades draw the viewer to ponder: how do we acknowledge others, our environment, and our own senses? And what necessary implications for action does this have in a world wrought with climate disaster?

The word experience is key: entering the exhibition, the interaction begins immediately upon stepping into the elevator. The viewer exits into monochromatic light, people mill around in black and white, bathed in yellow. In a way Elíasson here forces our perceptions to be reduced, rather than expanded, to something more minimal – literally black and white. Perhaps the artist is urging us to see the world as it is, without our obliviously rose-tinted glasses. This subtle action orients us into a curated emotional mindset before we enter the exhibition space.

In the first gallery is Model Room (2003) a large, room sized box of intricate curiosities, orbs and containers of different materials, sizes and levels. The work challenges our preconceptions of building and ways of architecturally using space. Next, the viewer enters into a large gallery presenting a combination of earlier works from the 1990s and alongside new creations. Yellow tones compliment green hues, earthly tones vibrate throughout. A massive wall is filled entirely with subtle green Scandinavian reindeer moss that creeps down to the floor. Guests are allowed to touch the installation, together; it is remarkably soft. As an Icelander I associate to home, summer, picking blueberries in the countryside.

Olafur Eliasson in collaboration with Einar Thorsteinn, Model room, 2003. Wood table with steel legs, mixed media models, maquettes, prototypes. Dimension variable. Installation view: Tate Modern, London. Photo: Anders Sune Berg. Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Purchase 2015 funded by The Anna-Stina Malmborg and Gunnar Höglund Foundation. © 2003 Olafur Eliasson.

Olafur Eliasson in collaboration with Einar Thorsteinn, Model room, 2003. Wood table with steel legs, mixed media models, maquettes, prototypes. Dimension variable. Installation view: Tate Modern, London. Photo: Anders Sune Berg. Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Purchase 2015 funded by The Anna-Stina Malmborg and Gunnar Höglund Foundation. © 2003 Olafur Eliasson.

Olafur Eliasson, Moss wall, 1994. Reindeer moss, wood, wire. Dimensions variable. Installation view: Tate Modern, London, 2019. Photo: Anders Sune Berg.

Olafur Eliasson, Moss wall, 1994. Reindeer moss, wood, wire. Dimensions variable. Installation view: Tate Modern, London, 2019. Photo: Anders Sune Berg.

Courtesy the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles. © 1994 Olafur Eliasson

A reflected pane of window light mimics the outlines of some recognizable urban structure. Made from negative space, the work imitates a natural phenomenon, a reality, like the title of this show suggests. Four long trays of chemical yellow water line the floor, as if in some sort of photosynthesis or development process. The water sloshes back and forth in a synchronized movement, a quiet reference to the ocean’s waves. A window mimicking the rain – the mechanical imitating reality, quite masterfully. Outside is an artificial waterfall built out of scaffolding; Waterfall (2019) of the few new works in the exhibition, again brings together the mechanical and the natural in an imitating replica. These works suggest to the growingly blurred lines between man-made and organic.

Another of Elíasson’s new works, a black orb entitled Your Planetary Window (2019) playfully disrupts our sense of depth perception in a mirroring illusion. It is not until we encounter the other side of this orb in a separate room that the game of this work is revealed. The face of the viewer on the opposite side is plastered across the orb, like a fish eye lens. The work functions as a one way mirror to another person’s interactions with the piece, the minutiae of the person and their experience on full display. As private participants, we interact together in this work, unknowingly at first, in an element of voyeurism.

Following, in a black room, a soft misting of rain falls to the ground, a dim spotlight highlighting it. The room is warm and damp, fresh, the sound is soothing, taking us to a quite specific place, personal to each. This is Beauty (1993) and it is, quite simply, beautiful; pristine, quiet, intimate. The movement of the rain captured in the colorful light is bodily and emotional, physical. We want to grab it, but feel only it’s wet ethereal touch. The drops crystallize on the ground in a mirroring effect. It is seamless, continuous.

Olafur Eliasson, Waterfall, 2019. Scaffolding, water, wood, plastic sheet, aluminium, pump, hose. Height 11 metres, diameter 12 metres. Courtesy the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles. Installation view: Tate Modern, London. Photo: Anders Sune Berg.

Olafur Eliasson, Waterfall, 2019. Scaffolding, water, wood, plastic sheet, aluminium, pump, hose. Height 11 metres, diameter 12 metres. Courtesy the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles. Installation view: Tate Modern, London. Photo: Anders Sune Berg.

© 2019 Olafur Eliasson.

Olafur Eliasson, Beauty, 1993. Spotlight, water, nozzles, wood, hose, pump. Dimensions variable. Installation view at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 2015. Photo: Anders Sune Berg. Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles. © 1993 Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson, Beauty, 1993. Spotlight, water, nozzles, wood, hose, pump. Dimensions variable. Installation view at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 2015. Photo: Anders Sune Berg. Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles. © 1993 Olafur Eliasson

Throughout this exhibition there is a warmth and happiness, a curiosity in exploration. We interact together, yet separately, as one participant. Elíasson captures an essentialness of group and simultaneously individual experience. For example, in Din blinde passager (Your blind passenger) (2010). Viewers enter into a 39 meter long room filled with fog and a soft yellow, monochromatic light that gradually turns white blue. Visibility extends only see a few feet in front, and the rest dissolves into a soft fuzz as your eyes work to adjust. People disappear and reappear, come in and out of focus. You are together, yet in solitude. And still, there is a calm serenity to this fog, like one is entering into the rays of the sun, welcoming a dewy unknown. You don’t know where your next step leads, but you walk forward, trusting, enveloped. Alone in the fog, something in me pauses. I rest here in this abyss of nothing, of sound and perception and smell, knowing that I am not, in fact, alone.

After, the viewer encounters another familiarly perplexing work of Elíasson’s, Big Bang Fountain (2014). Entering into a pitch black room, interactors are guided by the sounds of water splashing and crashing in a black abyss. At few second intervals a bright strobe flashes, showing for a split second an image in light of a drop of water. The drop is static yet in movement, imprinted into the interactor’s mind as glowing after image. Just outside, a circular shadow screen projects an image of a wisp of light that rainbows in color in an ethereal, otherworldly fashion. This object of light feels familiar but I can’t place it. DNA? The Milky Way? As people walk behind and around it the shape changes and morphs with shadows, mystically mesmerizing viewers.

Next, a kaleidoscope series; for example one life size creation that visitors can walk through like a shimmering black hole. One kaleidoscope piece reflects the viewer, the sky, the earth, and the city in endlessly repeating iterations. This coning of mirrored repetitions into one conflated object forces a cognitive shift as we perplex at new perspectives. As Elíasson explains in a wall text “kaleidoscopes offer more than just a playful visual experience. Multiple reflections fracture and reconfigure what you see. You are offered different perspectives at once, and understand your position in new ways. You might let go of the sense of being in command of space, and instead enjoy a kind of uncertainty.”

Olafur Eliasson, Your spiral view, 2002. Stainless-steel mirror, steel320 x 320 x 800 cm. Installation view: Tate Modern, London, 2019. Photo: Anders Sune Berg. Boros Collection, Berlin. © 2002 Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson, Your spiral view, 2002. Stainless-steel mirror, steel320 x 320 x 800 cm. Installation view: Tate Modern, London, 2019. Photo: Anders Sune Berg. Boros Collection, Berlin. © 2002 Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson, The Expanded Studio, 2019. Installation view: Tate Modern, London. Photo: Anders Sune Berg. © 2019 Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson, The Expanded Studio, 2019. Installation view: Tate Modern, London. Photo: Anders Sune Berg. © 2019 Olafur Eliasson

Elíasson’s spectacularly comprehensive exhibition ends with a large educational center, the Expanded Studio, that encourages a focus on climate change and our environment, alongside a background into his studio practice and its connection to these social issues. This is a space to play and create and experience together in an extension of the galleries. Here Elíasson presents a continuing effort to invoke a change in consciousness, a sensitivity to our planet and ourselves, a reawakening of a sense of agency and proactiveness in all of us. In profound fashion, the overwhelmingness of this exhibition is educational in such a subtle way, bringing us together, without the viewer quite even being consciously aware of it. It is beautifully all encompassing, yet simultaneously simple and distinct in its message, awakening us.

Yet, perhaps some of this social commentary could be turned back around onto Elíasson himself, and his own studio practices. While projects like Green Light, Ice Watch, Riverbed, the solar-powered lamp initiative Little Sun, and his eco-friendly restaurant endeavors are all commendably environmentally oriented, to what extent does the Ólafur Elíasson Studio promote self-directed sustainability? For example, what is the environmental footprint of shipping blocks of glacial ice from Nordic environments across the globe, of transporting a massive wall of Scandinavian moss to London? What carbon footprint do his studio staff leave on the earth, with the endless air travel of Elíasson, his 90 people on staff, and his artworks and installations. Elíasson actively works with the World Health Organisation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and policy makers and UN officials across Europe in the interests of climate change and renewable energy, such as the Sustainable Development Goals and the 2030 Agenda to fight against institutionalization and the slow progress of climate change efforts. Elíasson is certainly no self-proclaimed pioneer of zero-waste, fully sustainable practices, and he must have a self-awareness to this, but the irony can still be pointed out. Perhaps this is part of the point, to turn this critical eye to ourselves and the never-ending possibility to do more amidst the seeming impossibility of living a truly sustainable and zero-waste lifestyle. Like Elíasson stated in an interview with Wired Magazine in 2015, “I am very respectful of the people who are knowledgeable, and I say, ‘I don’t have an answer to the challenge, but I have a tool — it’s called creativity’ As an artist, I think I can co-produce answers.“ Perhaps through pondering this dichotomy, we can bring our own daily actions into some self-critique as well.

Daria Sol Andrews

Articles for Reference:

Dazed Digital 2018: https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/39096/1/artist-olafur-eliasson-little-sun-diamond-environmental-crisis-art

The Art Newspaper 2017: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/olafur-eliasson-there-is-ultimately-no-space-in-which-art-cannot-work

Art Territory 2017: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/art/what-to-see/olafur-eliasson-the-return-of-the-sun-king/

The Telegraph 2016: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/art/what-to-see/olafur-eliasson-the-return-of-the-sun-king/

Wired 2015: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/art/what-to-see/olafur-eliasson-the-return-of-the-sun-king/

It´s Nice That 2015: https://www.itsnicethat.com/features/its-ok-to-disagree-the-divisive-work-of-artist-olafur-eliasson

The Guardian 2015: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jun/21/olafur-eliasson-i-am-not-special-interview-tree-of-codes-ballet-manchester

ArtReview 2014: https://artreview.com/features/december_2014_feature_olafur_eliasson

Cover picture: Olafur Eliasson, Eine Beschreibung einer Reflexion, oder aber eine angenehme Übung zu deren Eigenschaften (A description of a reflection or, a pleasant exercise on its qualities), 1995. Spotlight, mirrors, projection foil, motor, tripod. Dimensions variable. Installation view: Tate Modern, London, 2019. Photo: Anders Sune Berg. Boros Collection, Berlin. © 1995 Olafur Eliasson.

The exhibition In Real Life is on view at Tate Modern in London until January the 5th, 2020: https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/olafur-eliasson

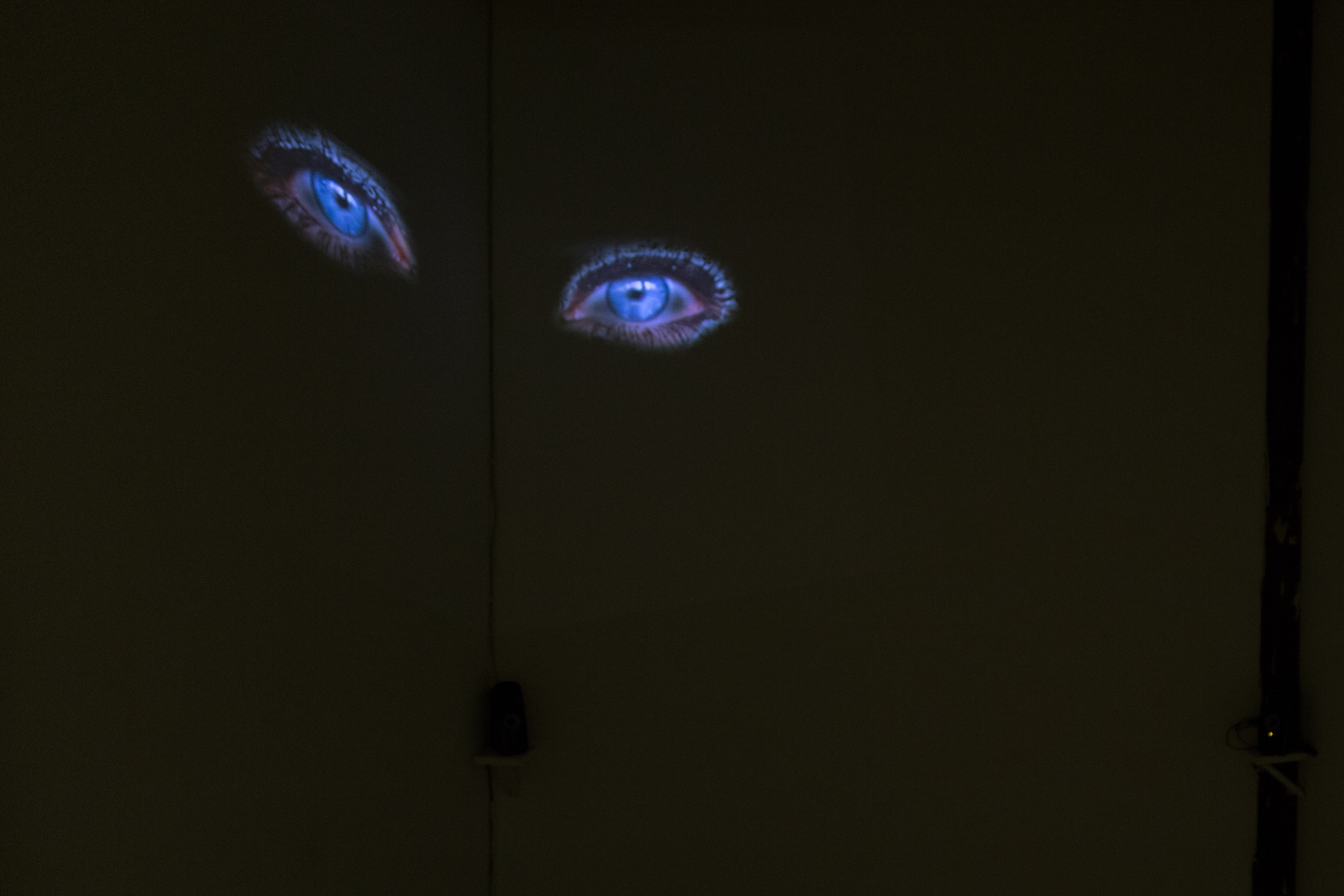

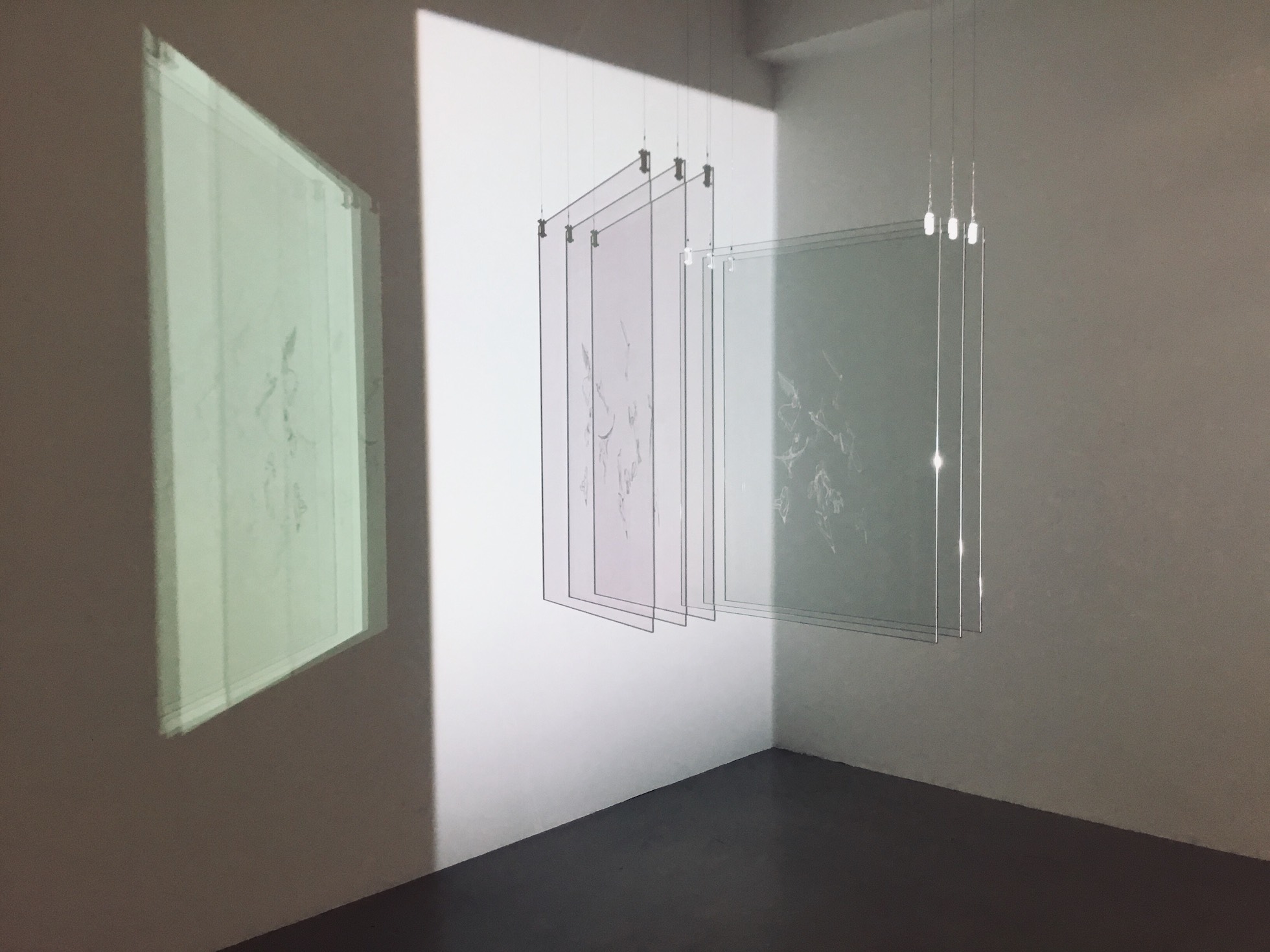

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery. Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery. Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.