Arctic Art Summit 2019: The Arctic as a laboratory for sustainable art and cultural policy

Arctic Art Summit 2019: The Arctic as a laboratory for sustainable art and cultural policy

The Arctic Art Summit is a biennial event established in 2017 which brings together art professionals, academics, artists, and those involved in the cultural field from Arctic countries to discuss shared challenges and to both encourage and support the establishment of circumpolar collaborations. The Summit was created to strengthen the art community in the north of the world, to focus on local art and to create infrastructures and opportunities for the nordic art to develop. This second edition was held in Rovaniemi, Finland, the capital of Lapland and homeland to the indigenous Sámi people, with conversations centered on the theme The Arctic as a laboratory for sustainable art and cultural policy. The event stretched over three days with conferences, discussions, exhibition openings, and artistic event where Arctic art and artists were protagonists.

The characteristics of arctic countries such as isolation, extreme weather, small communities do not affect the quality of art production, on the contrary art in these countries has maintained throughout the years certain specificities related to the particular history of those populations, characteristic which make it highly valuable. It is hard to define what arctic art is, to whom or what the term applies and how strict this definition should be, however we can assume that arctic art generally addresses indigenous and non-indigenous cultures in the nordic region. Thanks to their similar characteristics and histories, the arctic countries constitute the perfect ground for arctic artists to share their works, and for communities to establish horizontal orientated bonds which would disrupt the north-south movement of art. Creating microcenters outside of the traditional international art routes would counter the conglomeration of art in the big European or American capitals.

In a thoughtful speech, Dieter K. Müller, professor in Human Geography at the Umeå University, Sweden, highlighted that the arctic circle is “moving south”: more and more countries want to identify themselves as part of the Arctic region because that denomination would make them look more attractive to tourists’ eyes; “the Arctic is hot, in many senses” he said. The Arctic is hot because it represents the promise of adventures, stunning landscape, and exotic populations, therefore tourism has been on the rise in this part of the world during the last decade. Global warming is affecting the North faster than other parts of the world, the Arctic is literally hot and environmentalists look at what is happening up here in order to predict the trajectory of climate change throughout the world.

Dieter K. Müller giving a speech on the second day of the Arctic Art Summit. Photo credit: Kaisa-Reetta Seppänen.

Dieter K. Müller giving a speech on the second day of the Arctic Art Summit. Photo credit: Kaisa-Reetta Seppänen.

Müller expressed his concerns that this interest in the Nordic countries from the rest of the world might instill misrepresentation of those countries’ identities: Arctic populations need to define themselves by themselves, their image shouldn’t be shaped by the rest of the world. These beautiful lands so attractive to tourists are in fact inhabited by people, sometimes indigenous people, and instead of stereotyping them to attract more tourists we should learn from them, and leave them free to define themselves and to share their understanding of the lands they have engaged with for generations.

In the publication What is the imagined North? presented during the last edition of the Arctic Art Summit in Harstad, Norway, author Daniel Chartier, professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada, wrote that there are two visions of The North: the one from the outside, the representation of not-Nordic people, who arrived one hundred years ago, but have been imagining The North for many hundreds of years, and the one from the inside, the actual culture of the Arctic, which stems from the indigenous or native populations’ understanding of their lives in these lands, a knowledge passed through generations of inhabitants, shaped through years of living there and adapting their lives to the geography and environment. The indigenous framing, experience and definition of landscape and the Arctic has long been ignored by colonial history, and as such the idea of an uninhabitable Arctic took hold. The colonial voice dominated.

The management of cultural institutions and museums which gives more space to internationally recognised curators was raised as a concern by Müller, the implication of this is that they are more skilled and capable of representation in major institutions then local practitioners. Müller highlighted that it is fundamental to value local art professionals and to develop a stronger awareness of local culture and art, focussing effort on studying and researching them, to provide artists’ with platforms and opportunities to show their work. The main goal should be to reach a balance for local and international professionals who both have something to offer and the reciprocal benefit that can manifest. Cultural products from both sectors should be presented on the same level, to pursue post-colonialist values and restore a balance of power between dominant and marginalised communities.

Panel discussion Sustainability through Art and Culture in the Arctic. From left to right: Tuuli Ojala, Jan Borm, Gunvor Guttorm, Daniel Chartier. Photo credit: Janne Jakola.

Panel discussion Sustainability through Art and Culture in the Arctic. From left to right: Tuuli Ojala, Jan Borm, Gunvor Guttorm, Daniel Chartier. Photo credit: Janne Jakola.

2019 is the United Nations’ year of indigenous languages, this was acknowledged by Arctic Art Summit through giving prominence and focus on indigenous art, culture and language. Recurrent conversations asserted the importance and understanding indigenous language in order to understand indigenous art and culture. Gunvor Guttorn, professor in Duodji (Sámi arts and crafts, traditional art, applied art) at the Sámi University College in Guovdageaidnu/Kautokeino, Norway, highlighted the importance of keeping Sámi languages alive since they are key to understand the development of Sámi culture for they are strongly intertwined with the history and lifestyle of these communities. The Sámi University College, in facts, offers education in Sami languages, providing Sami people with the opportunity to be educated in their own language, a right of which everyone should be entitled. Tiina Sanila-Aiko, president of the Sámi Parliament of Finland, emphasised the importance of indigenous languages by giving a speech in Sámi language, an interesting experience for those in the public who didn’t speak the language, the particular sound of Sami words did however unveil certain characteristics of the culture itself. She stressed that language constitutes a mirror of a culture, it reveals the philosophy of existence, the values, and the perception of things. Language is a powerful tool giving insight into a culture, and for too much time indigenous’ languages have not been heard. At this year’s Summit, David Chartier empathized that “we have to preserve languages for ecological reasons, if we lose languages we lose ideas”. He explained that we are all connected within the world, and ecology is not just about nature and environment, but it is also about preserving humans’ cultural heritage. We need an ecology of the real, which takes into account everything existing around us.

Panel discussion Decolonizing Research Practices. Speakers: Krista Ulujuk Zawadski, Charissa von Harringa, Pia Lindman . Moderator: Heather Igloliorte. Photo credit: Kaisa-Reetta Seppänen.

Panel discussion Decolonizing Research Practices. Speakers: Krista Ulujuk Zawadski, Charissa von Harringa, Pia Lindman . Moderator: Heather Igloliorte. Photo credit: Kaisa-Reetta Seppänen.

Panel discussion Duodji in Contemporary Context. From left to right: Irene Snarby, Duojár Katarina Spiik Skum, Svein Aamold, Gunvor Guttorm, Anniina Turunen. Photo credit: Janne Jakola.

Panel discussion Duodji in Contemporary Context. From left to right: Irene Snarby, Duojár Katarina Spiik Skum, Svein Aamold, Gunvor Guttorm, Anniina Turunen. Photo credit: Janne Jakola.

People from different Arctic indigenous communities and people from dedicated art and cultural institutions which support indigenous’ art and culture took part to the summit, discussing the situation of the communities they work with and sharing how they operate with respect to indigenous communities, raising consciousness and discussing better ways to valorise indigenous art and promote an understanding of it from inside the community, avoiding displaying such works from a western standpoint, as mere exotic object. Indigenous’ art requires specialized engagement, and at the same time it’s important to open these dialogues to the world and placing them in conversation with mainstream art. Such works demand a presence global art community and to be engaged with at an international level.

The situation of indigenous art is delicate, in fact in order to understand and connect with their art one needs to be familiar with their culture and the way they live, indigenous art is often inseparable from indigenous people’s lives, their art is often expressed through objects used in everyday life, art research and functionality are often combined. Therefore, indigenous people should be included and consulted when art from their communities is the subject. Indigenous art professionals exist, and art institutions who wish to work with objects from indigenous communities need to have members from that specific communities operating on all levels of the institution. This falls within the process of de-colonisation, a hot topic in every cultural and non-cultural sector. Giving opportunity to those who had been deprived of any kind of powership over their own land, culture, image, of taking back their histories and validating their specialised knowledge and skills is important to re-establishing a balance between powers in the world.

The Arctic Art Summit left everyone with a positive feeling for the future of the Arctic. Thoughtful conversations, inspiring speeches, and insights into institutions who are really making a difference though their work with and for indigenous communities’ cultures, left participants of the summit hopeful that a future based on respect, understanding, and inclusivity can and will exist and that the research of and engagement with marginalised cultures will keep them alive.

Ana Victoria Bruno

Sámi band Soljio playing on the last evening of the Arctic Art Summit. Photo credit: Janne Jakola

Arctic Art Summit website: https://www.ulapland.fi/EN/Events/Arctic-Arts-Summit-2019

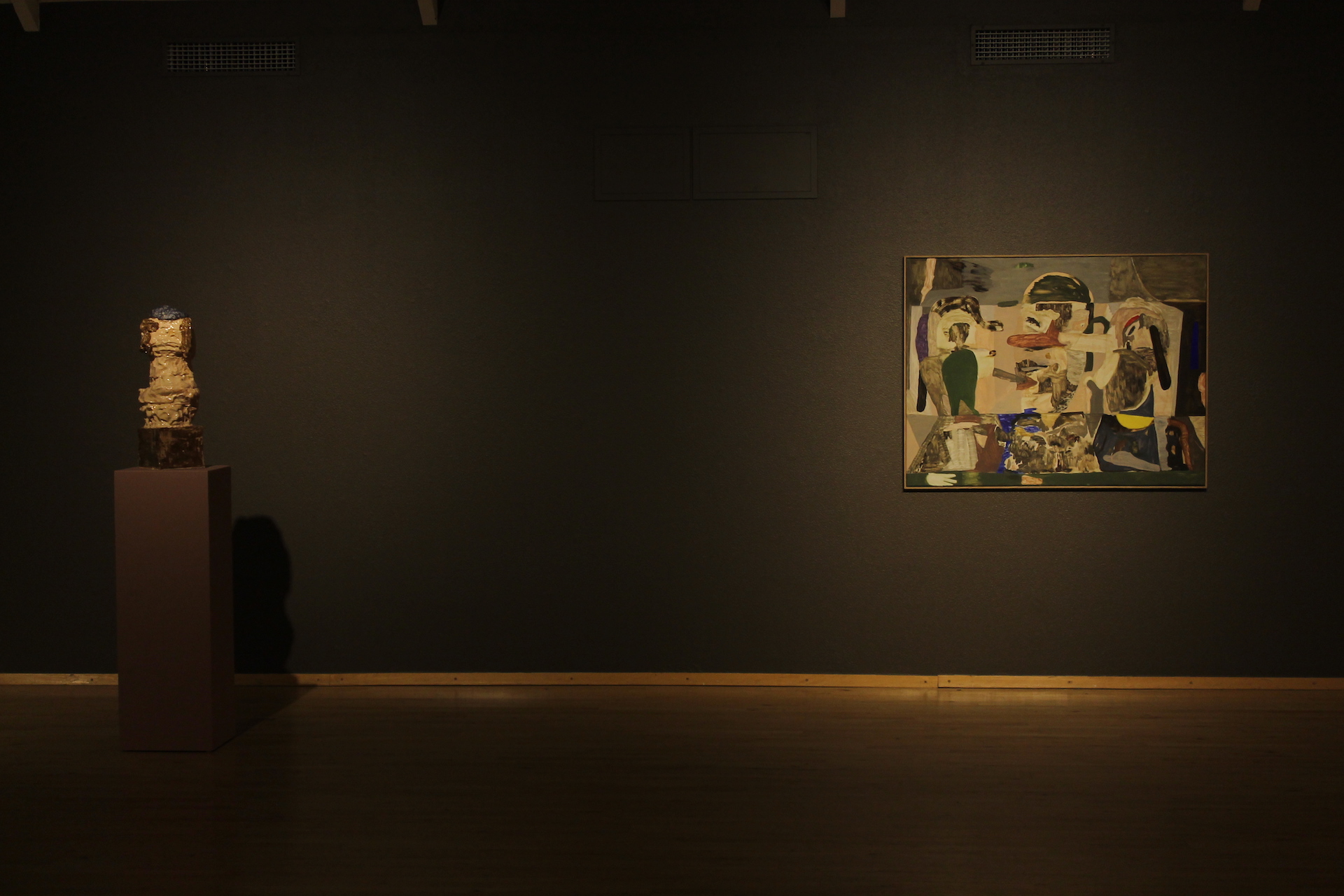

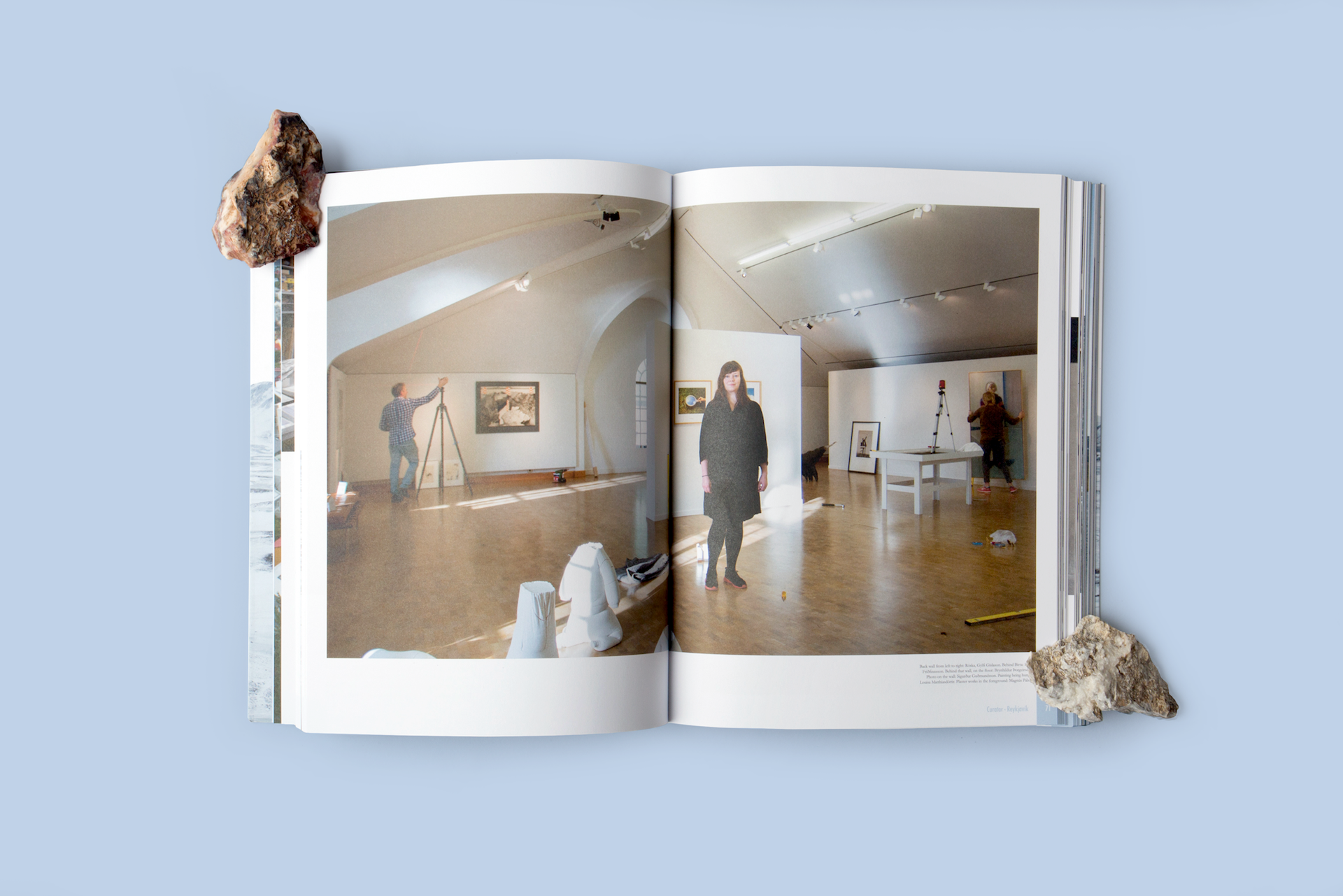

Cover picture: installation view of the show Fringe at Galleria Valo, Arktikum. The exhibition focused on art and crafts from the Arctic periphery runs from June 4 – August 11, 2019. Photo credit: Kaisa-Reetta Seppänen.

Sigurður Guðmundsson, Eggin í Gleðivík, Djúpivogur, 2009.

Sigurður Guðmundsson, Eggin í Gleðivík, Djúpivogur, 2009.