Museums in the time of CoronaVirus – A Conversation Around Digital Efforts

Museums in the time of CoronaVirus – A Conversation Around Digital Efforts

The rise of Covid19 and the government imposed social gathering ban has taken its toll across all cultural platforms of consumption in Iceland, not least of all on the arts. Many museums like Hafnarborg, Gerðarsafn, Listasafn Árnesinga, and Nýlistasafnið, to name a few, have had to temporarily close their doors while our country comes to grips with this health crisis. The Icelandic art scene is a small but flourishing one, but one of course, like all others across the globe, which is dependent on social interaction.

How have art institutions been dealing with these imposed regulations and closures? Hafnarborg was forced to cancel or postpone all concerts and guided tours, and have rescheduled their DesignMarch exhibition until June. Gerðarsafn has postponed two exhibitions until the summer as well. Thankfully, having to temporarily close their doors won’t have massive repercussions on most museum programming, as Kristín Scheving at Listasafn Árnesinga explains: “as all museums in Iceland we needed to close the doors to the public but that didn’t really stop our programming, we just had to postpone some events and move some to the internet. As this situation will come to an end, it won’t change anything for us in the long-run.” This alienating time has then opened up possibilities for museums to take on important projects that have been on the back burner. At LÁ Kristín tells me they have been using the time for renovations, “We have been using this time usefully, with fixing interior issues for example: building walls, painting walls, installing a new major AC system with a dehumidification system which would have been hard during open times.” Nýló, Listasafn Árnessinga, and Gerðarsafn have all increased their use of social media and are thinking of ways to be more digitally visible. In this way museums have been making the most out of an unideal situation and creating something positive out of uncertainty.

Hafnarborg has used the extra time to create digital material that can be experienced online, for example sharing a concert recording of Jennifer Torrence performing Tom Johnson’s Nine Bells. Ágústa Kristófersdóttir, the museum’s director, explains that they signed a contract with Myndstef “which has been in preparation for some time now and allows the museum to share images of the collection through the online database Sarpur (www.sarpur.is). Then we are also producing short videos with guided tours of the exhibitions, as well as music performances – since our music program is a very important part of our work.”

At Gerðarsafn, director Jóna Hlíf Halldórsdóttir and her team have created an exciting live streaming project with the Culture Houses of Kópavogur (Menningarhúsin) and the newspaper Stundin called Culture at 13/Kúltur klukkan 13. “We have asked Einar Falur Ingólfsson and Halla Oddny Magnúsdóttir to discuss the exhibition ‘Afrit’ (e. Imprint), and then we got three artists to talk about creative projects for families, which we call Gerðarstundin (e. ‘Gerður’s Workshop’). The artists introduce fun and interesting ideas that children and grownups can create from simple and easily accessible materials at home. All the events can be seen through the Facebook pages of the Culture Houses and Gerðarsafn.”

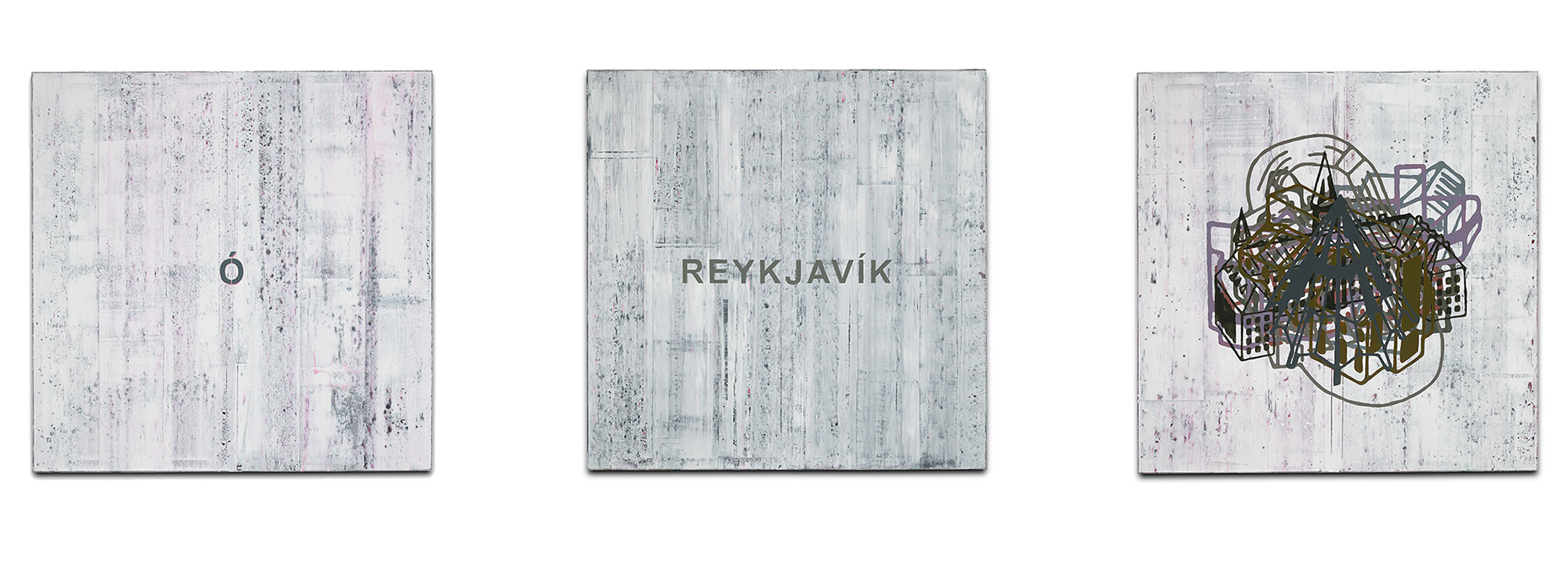

Courtesy of Hafnarborg.

Courtesy of Hafnarborg.

Gerðarstundin (e. ‘Gerður’s Workshop’). Courtesy of Gerðarsafn.

Gerðarstundin (e. ‘Gerður’s Workshop’). Courtesy of Gerðarsafn.

Courtesy of Hafnarborg.

Courtesy of Hafnarborg.

In considering potential economic repercussions, for Hafnarborg at least Ágústa explains that the museum is run by the municipality of Hafnarfjörður and only a small percentage of resources come from other sources of income: “aside from our more apparent activities, collection and preservation are an important part of our roles, which we have chosen to focus on during this crisis – a part that quite often gets put aside due to the hectic schedule around events and exhibitions.” Similarly at Gerðarsafn, crowd control measures will not have major impacts on the museum in the long run, as Jóna Hlíf tells me: “Of course this unsettles our exhibition program and affects our artists and technicians. I think this is a challenge, but we are in a favourable position as we are not all-dependent on income from tickets or visitors.”

In this vein, at a time of such global distress and panic, it is easy to question why we should even be worrying about art and culture when the global perspective requires much more dire attention. Why is art still important, relevant even, in times of global crisis where more urgent matters seem to take the forefront? As Dorothee Kirch at Nýlistasafnið says “art is food for the brain and heart. It will always be important and relevant.” Art has the potential to “release people from the constraints of fear, oppression and prejudice”, as Jóna Hlíf explains: “as a mirror for society, as an influencer and as the critic’s voice. Art is by its own nature indestructible and unbreakable, yet at the same time constructive for the mind and the soul.” Kristín relevantly points to the important healing possibilities within art as well, particularly in a time like this: “It can help you reflect on the situation, it can move you and it can teach you.” Art is perhaps especially important precisely in such a moment of global uncertainty – as Ágústa mentions, “Art can make us see the world and ourselves through a different lens and when, if not now, isn’t that necessary?”

The increased virtual presence of museums in these times does however in a way function as a “band aid” solution for our current situation, as Dorothee comments: “I am happy to wait until the pandemic is over to enjoy an exhibition with all my senses again. For me, the virtual platforms will never replace the real bodily experience of an artwork or exhibition, no matter what medium. It has too much to do with our perception of our surroundings in relation to our body. No virtual platform can create that. I believe that Art is a reflection on how we stand in the world, but to experience it we, well, have literally to stand in the world… not look into a window…” Of course nothing can replace an in person visit to a museum, but like Kristín at LÁ points to, “I think (digital efforts are) a wonderful way to reach those who can’t come here. Not only during these times, I have been talking with artists who are making a project with inmates in Litla Hraun (a prison in the county), which I am very interested in collaborating with them in. A virtual tour of an exhibition for someone who can’t come here could be a really interesting way to reach out. Also to people who are in hospitals and so on, children who live far away from the museum etc.” Jóna Hlíf also comments on the importance of the physical museum space in itself. “Museums are not just places to experience art, but also places to come and meet other people, enjoy and create. Gerðarsafn is a venue for active discussion and powerful collaborations and we seek to connect to our guests in new ways, to deepen the discourse, interest and understanding of art and culture. Museums are places to pause and to be with others, for contemplation and fulfilment and for channelling provocative and/or challenging ideas.”

In this way, although we cannot fundamentally experience art in the same way through a computer screen, some positive implications to our current situation can be gleamed. Ágústa says that the current closures “have really helped us gain confidence in that (digital) matter and take more active steps in that direction. Of course, it will not replace the real thing, but it is a very welcome addition, I believe. Like many others, we have thought about branching out in this way before, increasing our visibility on social media, but such ideas or projects often get put aside in favor of the day-to-day schedule.” Similarly, the Culture at 13 programming at Gerðarsafn is something Jona Hlíf plans on utilising in the future; “It is both a great way to access art by those who do not have a chance to go to museums, or are forced to stay away because of sickness or distance. Also, this can become an important archive for the museum and the artists.” These virtual efforts raise interesting debates for how our society may permanently change after the Coronavirus, with regards to how we experience culture. Perhaps post virus we will see a society that is more and more characterized by virtual art experiences and online platforms. How can we continue to support our favorite producers, exhibitors, creators of art in such uncertain times? Visit Gerðarsafn after the crowd controls are lifted, “and even invest in an ‘árskort’ (e. annual ticket) to the museum. We will have a need for meeting, seeing something new, living, creating and enjoying again.” At Nýlistasafnið, Dorothee suggests becoming members or “Friends of Nýló” through their support program, or buying Christmas and birthday presents in their museum shop. Kristín similarly asks the public to be supportive of Listasafn Árnesinga on social media, “keep on reading and learning about things. Use the internet in a positive way. Learn things!” Ágústa recommends supporting Hafnarborg by watching “the content we are creating, ‘like comment and share’ with family or friends. This is a time when we all must find new ways of establishing connections with each other, both as individuals and institutions.”

Daría Sól Andrews

Gerðarsafn: https://gerdarsafn.kopavogur.is/

Hafnarborg: https://hafnarborg.is/

Listasafn Árnesinga: http://www.listasafnarnesinga.is/list/

Nýlistasafnið: http://www.nylo.is/en/