Mapping Time both Eternal and Material with Gretar Reynisson

Mapping Time both Eternal and Material with Gretar Reynisson

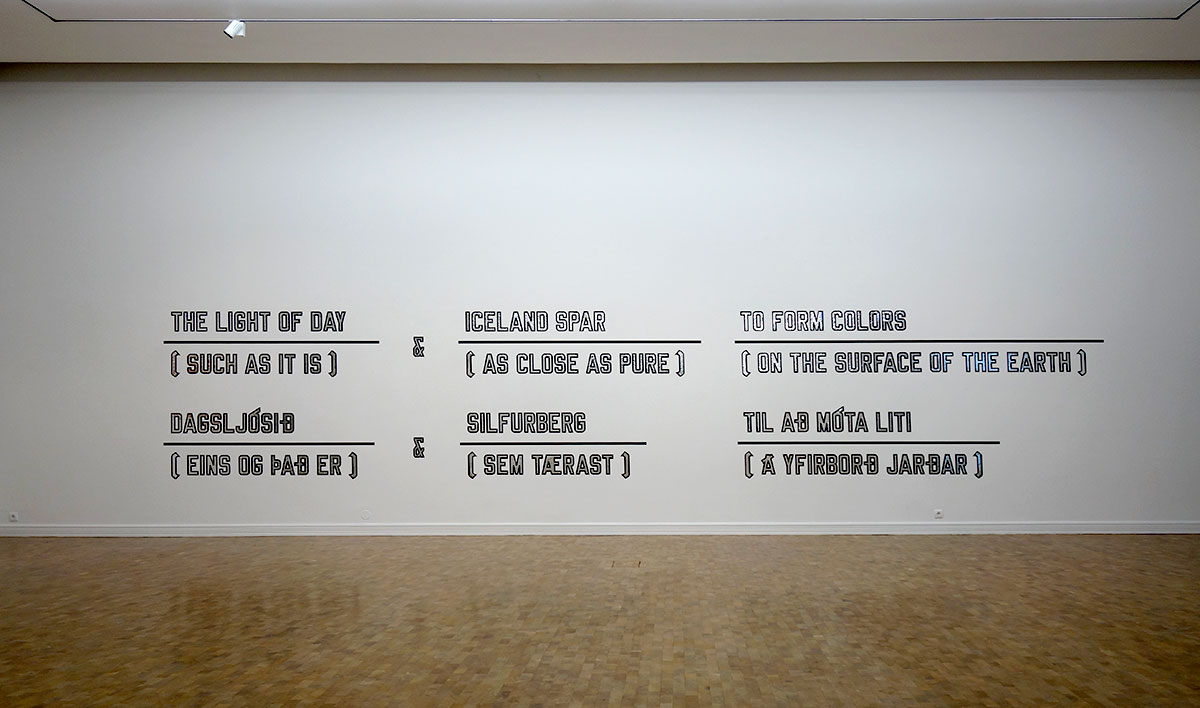

Although possessing a material reality, time exists without needing to be represented nor is its representation necessary in the experience of time. With time-based artwork such as that by Gretar Reynisson, the experience of time is visualized into a form on the minute line between the personal and the universal. The experience of time is given aesthetic effect as ‘the time of art’ itself. It is not comparable to the time of the museum’s opening hours, or the duration of a film, or the time it takes to get from one place to another, although it can contain all of these elements.

Space and time, as the foundations of human perception, fragment and perform a distortional effect on the senses depending on how it is framed. Time appears as linear with the past disappearing and the future on the horizon, with the present as a stepping stone balanced somewhere in between. This is the place, the moment, and the vicinity in which Gretar Reynisson expands his timeline, creating a ripple in the timeline of those who come into contact with his work. These time-based works create a ripple all their own, affecting the ‘time of art’ itself.

By measuring time with the precision of its material reality, he has expanded the present moment by mapping time with ritual and material, but it is not the ritual that would require any incantation, as it is the expanded moment of daily life where it is lived every day in the very physicality of the body and its processes that the real transformation from one moment in time to the next is charted. Something in the experience of this mapping of time automatically gathers a momentum all its own, and it is part of the map that you don’t have to see to know that time will indeed continue without this mapping. This knowledge overlaps with the everyday map of time, and you see and know that time will continue into eternity and we are tiny blips on that eternal map.

20 40 60

At Neskirkja from April 2nd to June 25th, 2017, the artist presents the exhibition 20 40 60, celebrating the 60th birthday of the artist as well as the 60th birthday of the church itself. The title comes from a photograph the artist took 40 years ago at age 20, of his hand next to the impression his hand has made in mud, which the artist restaged earlier in 2017. Both photographs can be seen in the exhibition, each referencing the line from Genesis 3:19- By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return.

During a performance accompanying the exhibition, guests were invited to make their own fingerprint impressions with mud on the walls inside the church’s gallery- 500 to be exact. This corresponds to the 500 years that have passed since Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg Germany, which marked the beginning of the Reformation and changed the course of history. At Hallgrimskírkja, the artist has filled the vestibule of the church with 500 nails each with a corresponding tag for the years between 1517 and 2017. This exhibition, titled 501 Nails is on exhibit from May 21st to August 21st, 2017.

On the exhibition walls at Neskirkja, the fingerprints are like constellations with the tiny crevices of individual lines inside each marking visible. On the opposite wall, you see the white towels that each person used to clean the excess mud from their fingers as another kind of memento mori of the body in its interaction with surfaces and materials. With these impressions, it is as though the material evidence is what holds the memory of time between realms. The material tells us everything we know and brings the viewer or participant into the epic story in which we all take part. There is something reminiscent of a wall of prayer where people come to meditate in the mud fingerprints. With the ancient text reminding us that we shall return to this earthly material, the span of time between becomes impressionable- as the fingerprints pressing on the walls of the church are attempting to weigh the structure itself and what it stands for against the existential weight of time that we face every day.

Like the still-life painting theme memento mori which began as early as the 16th century and was most renowned in Northern Europe, the mud fingerprints are one in the same as the objects so often depicted: rotting fruit and vegetables, withering flowers, skulls, hourglasses, smoke, bubbles, and usually a surface with the glint of a reflection of the artist themselves. These objects symbolized the ephemeral quality of life in its fleeting nature, a precursor to time-based artworks. The artist considers the quality of time as a subjective, interactive entity in which the practice of image-making is tandem with learning how to visualize time. The phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty described the act of perceiving as an act akin to drawing: “definite qualities only draw themselves in the confused mass of our impressions if it is put in perspective and coordinated by space.”[1] In this way, Gretar Reynisson’s mapping of time with material objects in his everyday life brings order to this massive array of perceptions shaped and gathered by time and space. He maps the coordinates as a meditation on being present in the everyday.

More About the Artist’s Previous Time-Based Works

1,461 Days

Twenty years ago, Gretar Reynisson began a series of works in which time and the objects making up the artist’s everyday life were interwoven. Work produced in this manner was exhibited at Kjarvalstaðir in 2001 under the title 1,461 Dagur (1,461 Days) corresponding to the time period from January 1, 1997 to December 31, 2000. In 1,461 Dagur, the artist methodically worked over four years, with each year documented according to, in chronological order: days, weeks, months, and finally, a year.

In 1997, each day was recorded as a graphite drawing onto a 12 x 12 cm wood plate and corresponding to this were face rubbings made by the excess graphite dust created by each day’s drawing. In 1998, weeks were recorded as graphite drawings onto 21 x 21 cm wood plates. These more detailed works gave further inquiry into the weight of time and how it shapes our actions. Accompanying each day in 1998, the artist also baked a small loaf of bread, a religious allusion that straddles both eternal and physical time. In 1999, a 31 x 31 cm wood plate is created for each month of the year as a graphite drawing. The graphite mandalas of subtle circular impressions pull the viewer into the spiral of existential time. Corresponding to the plates are coffee diaries, one with a coffee stain for each day from the artist’s daily coffee cup. The year 2000 was measured by objects left behind after their initial purpose expired. Taken as a whole, the year is exhibited as 52 bath towels, one from each week of the year, with the accumulated bodily impressions of the artist in the object. The artist presents a 100 x 100 cm wood plate for the year as a graphite drawing showing repeating undulating spirals, like the zoomed in reflected material from a painting by a Dutch master, an esoteric reflecting glass held in the palm of a child.

Decade

Gretar was honorary artist at Sequences festival in April 2013, at which his work titled Áratugur (Decade) was exhibited, involving works from 2001 to 2010. Decade shows ten graphite plate drawings, one for each year in the decade, 52 white button-up shirts- one for each week of 2001, 12 pillows- one for each month of 2002, 365 labeled drinking glasses- one for each day of 2003, notebooks from 1999-2004 with the same sentence written repeatedly, 12 invoice spikes for each month of 2004 each full of invitations and envelopes, 12 doormats for each month of 2003, and all the way to 2010 including doormats, skin flakes, paper. This meticulous attention to the subtleties of living and the way that time takes its toll on us has the transformative effect of making time appear as extremely malleable and as a structure which bends at our will, not the other way around. Decade compresses ten years into a ten-day exhibition. The tediousness of documenting time is well preserved.

Erin Honeycutt

[1] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (London: Routledge Classics, 1962), 251.

Photo courtesy for all photos by Edda Björnsdóttir