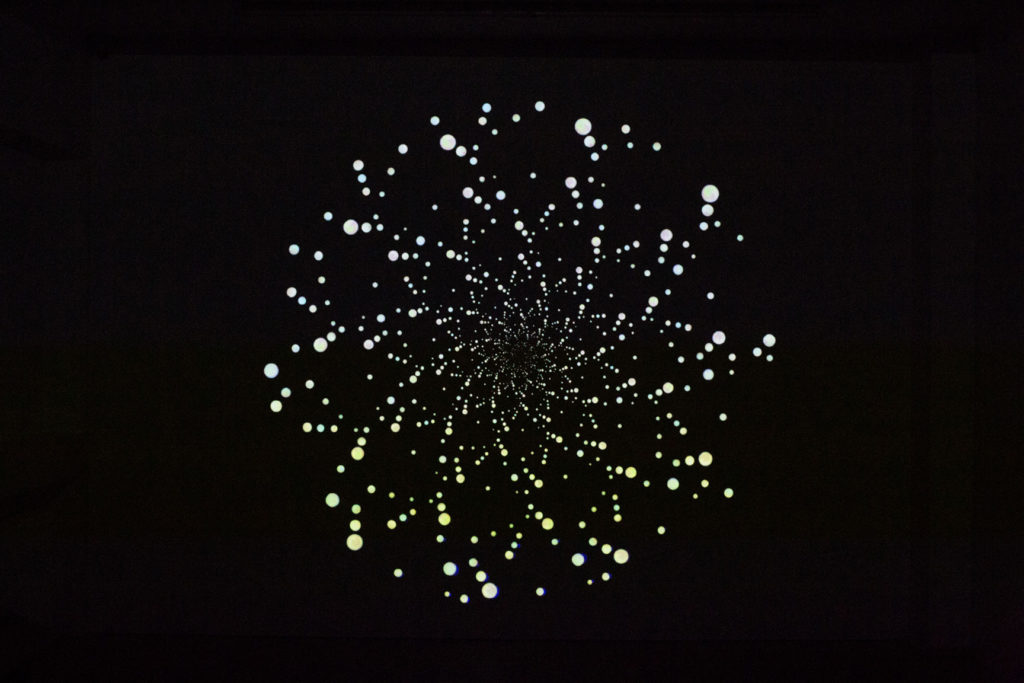

Dodda Maggý’s exhibition Variations is on view at BERG Contemporary from August 18th to October 21st. The artist was recently awarded the ARoS – Aarhus Art Museum’s Young Talent Award. Using sound and music as departure points, the artist further compounds their intertwining by using rhythm and narrative to engage the senses. Her animated symmetrical compositions explore the experimental possibilities of translating sound into visual form with a technical mastery of the formalities of harmonics and how these form the basic formations of the universe. With a dynamic interplay between the parts and the whole in the image, the patterns appear as though in perpetual evolution, like a kaleidoscope. In an in-depth interview, the artist explains her complex working methods as we walked amongst her work.

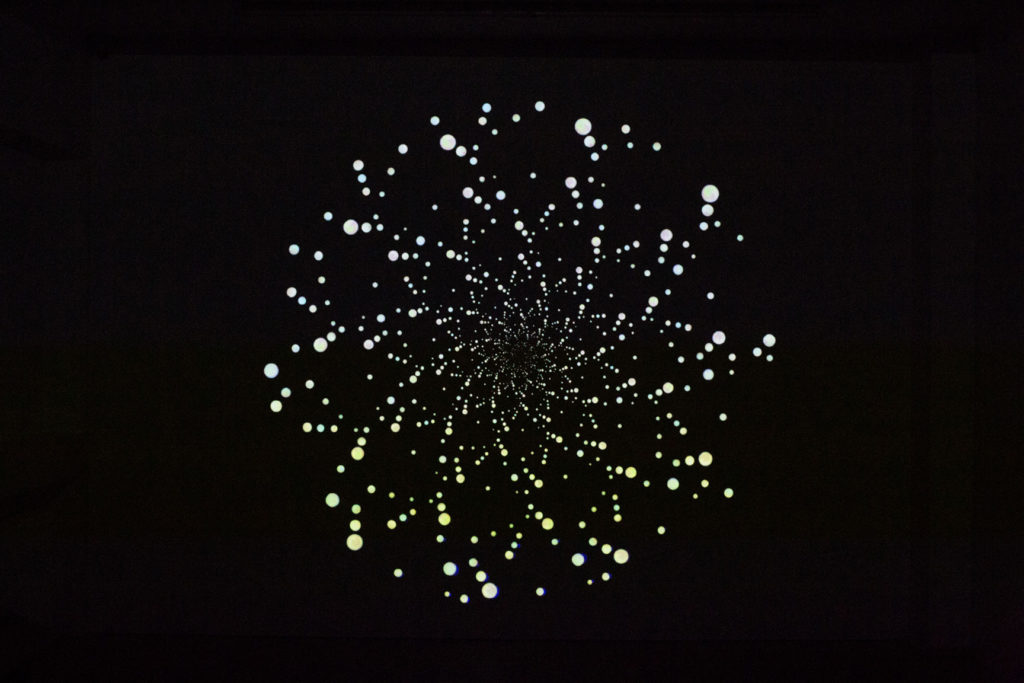

Erin: Can you tell me about this piece (DeCore (etude))?

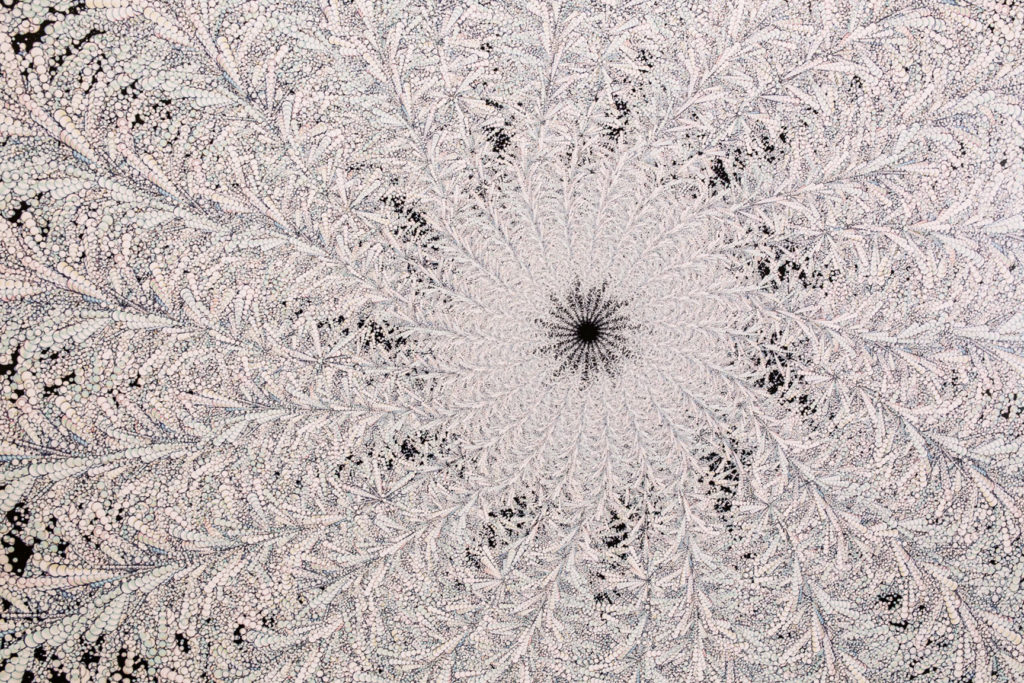

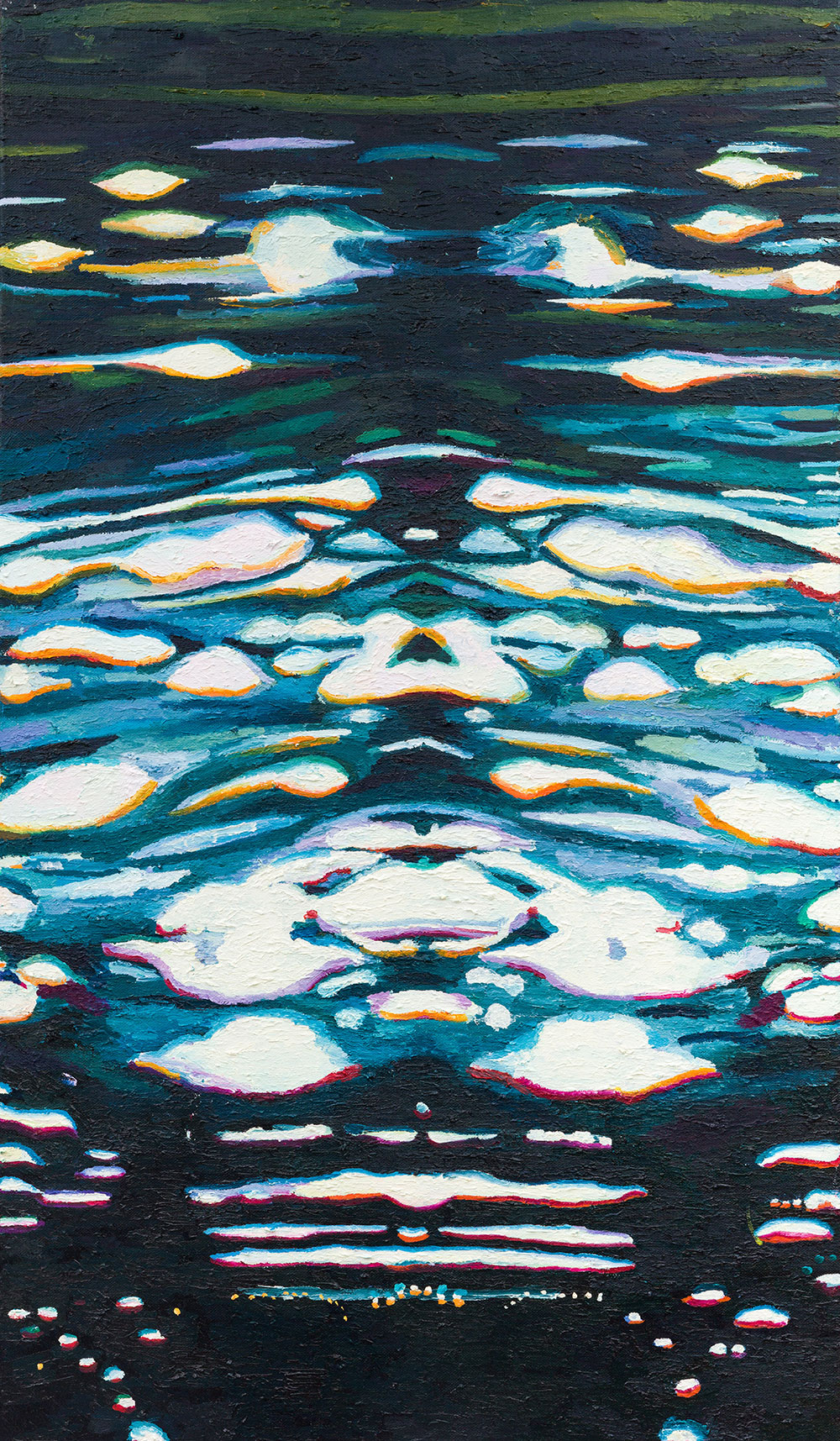

Dodda: So this is an ongoing series called DeCore that started in 2008. When it started as a video I was working with methods of applying field recordings and sounds to video. I basically went around with my video camera and filmed flowering plants and trees and then started to manipulate that material to create new organic forms. The first version, which was called DeCore (aurae), took me three years to figure out the right form. I was thinking a lot about visual music as well as synesthesia, the state of having your senses crossed that causes people to see music or experience forms as colors. I was applying these methods and sounds to video and also thinking about how to represent music. DeCore was then installed as a large silent installation, followed by another version, and now I’m showing two of the newest versions here, DeCore (etude), and DeCore (loom). It’s the same source material of trees and flowering plants, actually.

I’m continuing to resample in this exhibition. However, I’m not re-sampling the works themselves but going back into the source material and making new manipulations- almost a remix of the original recordings. With this piece, I actually wanted to take the source material and create print stills. It’s another thing to really create the image rather than take a still, so I created the video in order to take the still image.

There is a lot of crossing of mediums in the show. I wanted to create a technique in order to create prints as this is my first show exhibiting prints. Usually, I’m only working with video, music, and sounds so I had to create a technique that I could relate to in order to create still images. When you’re used to working with time-based art, which is always moving, you have to recalibrate how to translate this movement into a still image.

Erin: It’s going from 3D to 2D, so of course, it’s a huge recalibration.

Dodda: You have to think about it differently. So this is like the DeCore series but evolved. I’m still thinking about music here and I think music is still the understory of everything I do. I start with music before visual arts.

Erin: You studied both right visual art and composition, right?

Dodda: I studied both. Before I went to university I felt like I had to make a decision between going further into music or visual art and I chose visual art because I felt there was space for both. Later, I finished studies in composition as well. I think as a visual artist, I really connected with video and this time-based medium because I understand it as it relates to music.

Erin: It’s as though your process of making videos is an image of harmonics itself, so your work is both in the medium and the resulting image.

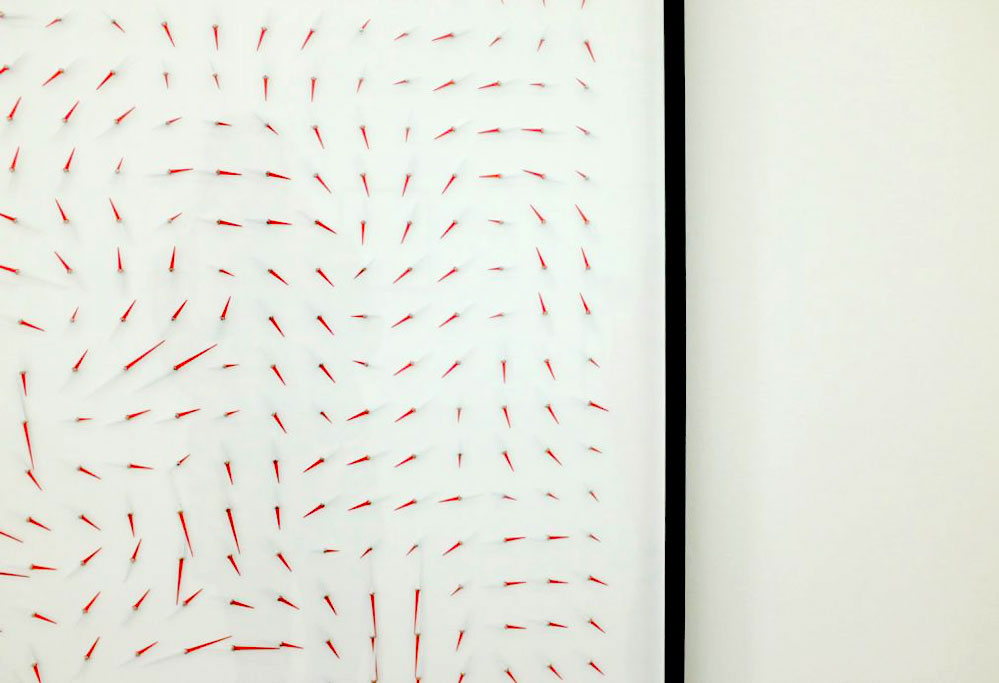

Dodda: That’s my aim, but we can debate whether it comes forth. In this piece with these small sorts of flowers, each flower is made out of many recordings of flowers, so there are many details combined. In just one little flower there are multiple processes happening at once. I like the size of it because you can see the details.

Erin: You’re making your own language, it seems, by working with each note in itself and making them work together to become its own vocabulary. What programs are you using?

Dodda: I use a lot of programs of all kinds and am mixing all of them. It’s my own method of layering that I developed with many variations.

Erin: The last exhibition here at BERG was of Steina and Woody Vasulka, the video art pioneers. They were some of the first to make tools that would manipulate audio into visual and vice versa.

Dodda: There is definitely this link. Steina actually was also trained as a violinist first. Having a background in music seems to be the case with a lot of video artists, especially in Iceland.

Erin: Narrative and rhythm seem to be two intertwining themes in the exhibition, each carrying the other forward.

Dodda: That is definitely the case with the videos, especially this one that I’m making to create prints from. I’m making the videos with this musical application and thinking about proportions. Just like with different chord combinations and sounds that make major and minor chords, we also have these proportions visually which create tension or harmony in the image so there is also geometry involved. I’m applying a set of movements to this, as well as colors obviously. This is much more monotone, I would say, but maybe baroque monotone. The first DeCore had each frame changing and was more chaotic but this is more still. It holds the shape but it still changes in color. This looks a lot like rhythms, almost like beats.

Erin: I was reading another an early article about your work about how your work engages the viewer visually but the rhythm engages your body, so it somehow traps you between these two states of being when you’re watching it. Perhaps this was more the DeCore installation when the viewer could be part of the projection and be very physical, but I think it still has a very mesmerizing effect on both body and mind.

Dodda: I’m very interested in these sensorial effects. My earlier work was more portraying these different states while now I’m more interested in creating this effect for the viewer. I know I can never estimate how the effect will be on the viewer, but I can stimulate some senses, definitely.

Erin: Where does the name DeCore come from?

Dodda: DeCore comes from something on the verge of being decorative, which is a total taboo. When I starting working on DeCore in 2008, to do something decorative or visually appealing was almost like porn. So I’m playing with crossing that line and questioning if it being visually appealing makes it less interesting. I’m playing with these aesthetics about how the proportions and harmonies bring affects. It’s also on a fine line to do something flowery so there is also a play on that. There is so much information in each frame, really, so I’m just pumping information out.

Erin: Isn’t it like that with music? Why is music allowed to be harmonious but not visual art?

Dodda: It goes in circles. After the Second World War, Romantic music was just not allowed. So, really serious, atonal music came into fashion because this Romantic music was connected to nationalism and it was totally out. It really just goes in circles depending on what is accepted at the time, beautiful music or atonal music. I think there’s been a shift in the last ten years, although it’s almost hard to say this out loud. I feel a shift from a focus on very theoretical to a slightly more Romantic, or more spiritual aesthetic. I think the themes I have been flirting with are actually being more accepted whereas before they were a little bit ‘outsider’.

Erin: I think it is definitely a noticeable shift.

Dodda: I don’t know if it is a trend, but it is definitely more accepted. Even before, to talk about energy, was a bit out there. It wasn’t really what my teachers were going for when I was in school, either. I can’t generalize it but I can definitely feel a shift in the atmosphere of what is going on and what is accepted.

Erin: The new age needs a new age, it seems. Is all of the work in the exhibition a variation of DeCore?

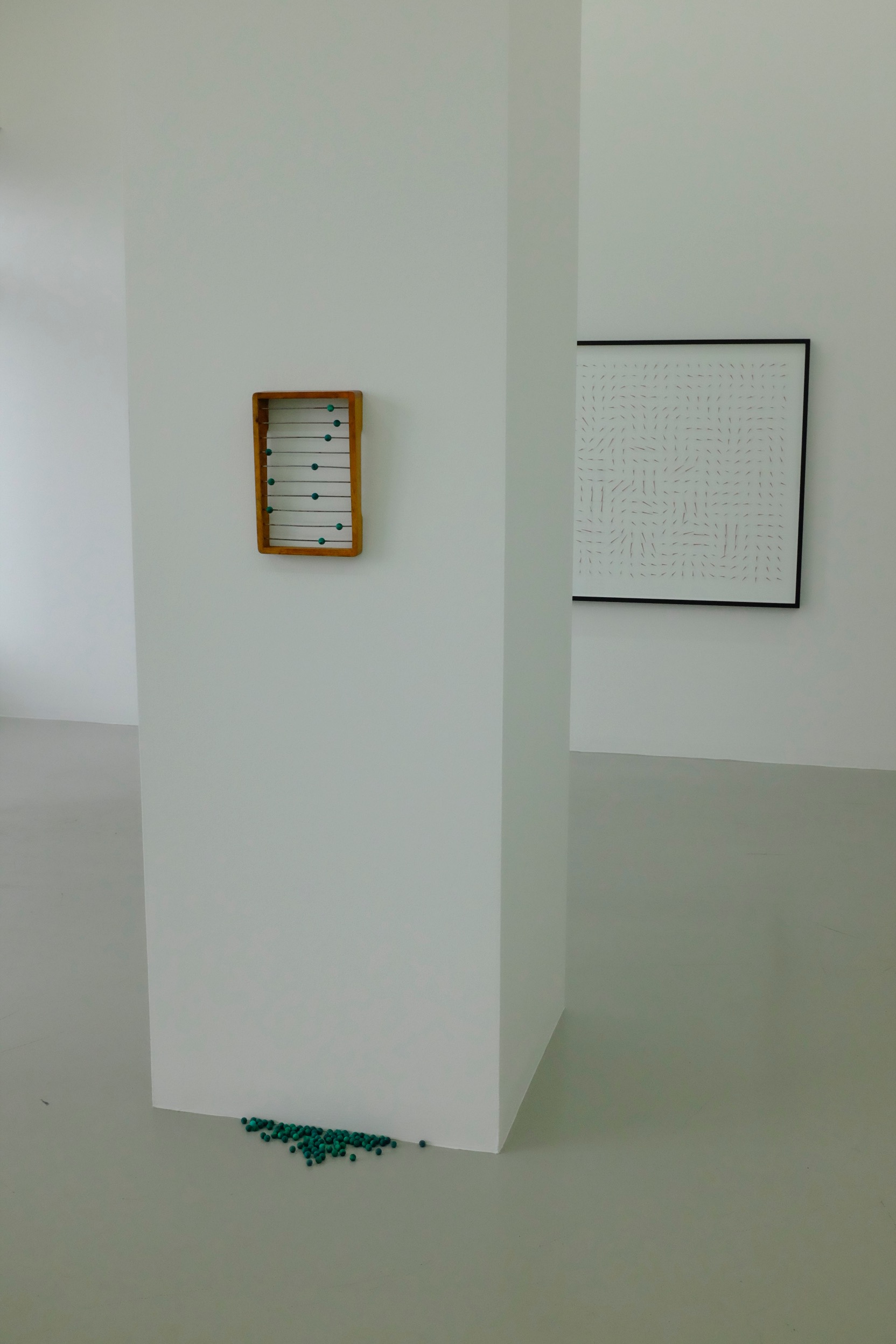

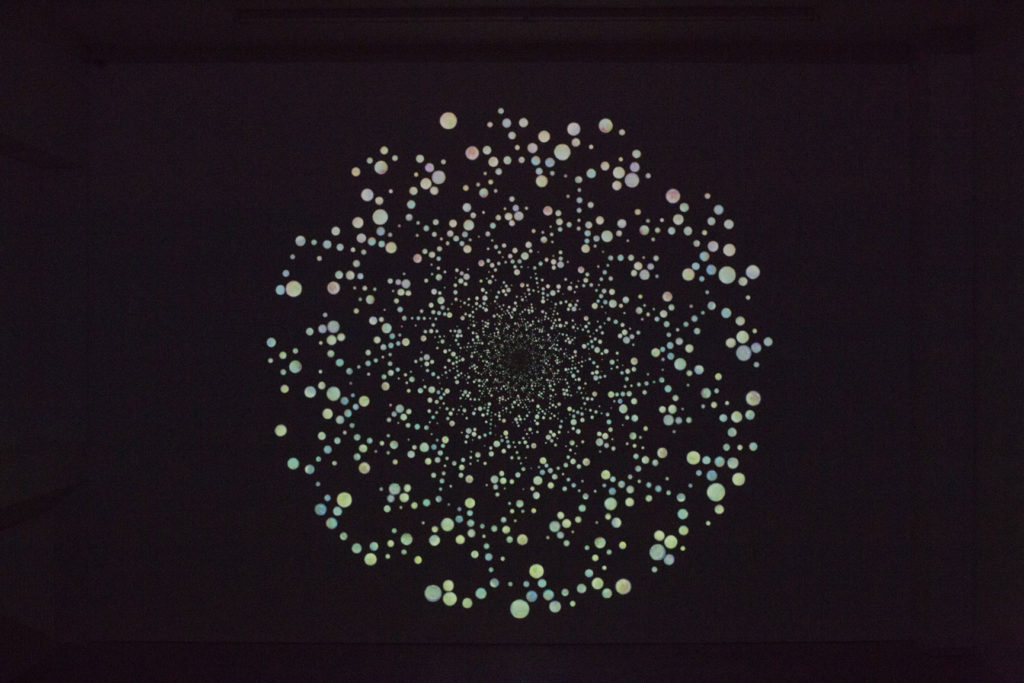

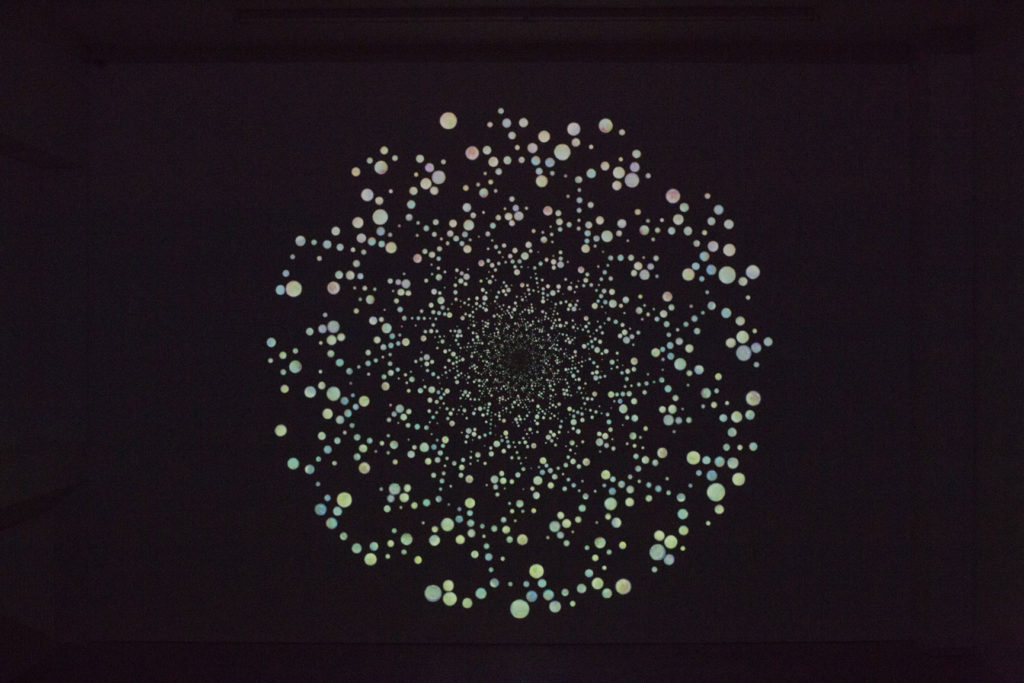

Dodda: No, there are three variations. We have three main pieces: DeCore, C Series, and Étude. Moving from DeCore to C Series, I am really continuing to investigate this relationship between the visual and the aural. I was interested in making a technique of composing using video and music but here I am much more in composition mode. I’m studying the flute as an instrument. I picked fifteen notes to work with and composed them in this one composition that is part of the exhibition, a nearly 18-minute long piece.

I made these video forms, a circular form with different proportions, for each of the 15 musical notes. Then, I connected each note to this form and I created a video animation with the music corresponding to what is happening in the video. With each composition, I pair a note to a form, which creates the musical composition. Later, I decided to remove the video and compose on the base of sound. I have one video from this process, but I’m only going to show the notes. When I was making the composition, I made another video from the same source material which became Coil, a part of C Series.

C Series is the focal point for the composition and so the accompaniment for the music, but then in the working process, I realized I didn’t need it. I’m just showing the music, like a work in progress, that shows how I composed this piece. If we go into the purely musical side of it, it appears as though I’m working in music. However, I’m not that interested in just composing. I’m interested in detuning.

We have this modern way of tuning instruments at 440 hertz. All instruments are tuned after that, but there is an older tuning at 432 hertz. When we tune after that the harmonics are a little more balanced. There are a lot of different theories about why we changed it, mostly conspiracy theories, but no one is really sure. So the tuning today is a little bit harder. You can see in visuals of chords how the frequencies make different forms.

I was thinking about how interesting this conflict is and wanted to start to detune my notes. I’m working from the range of 440 down to 432 up to 448 hertz so my instrument is mistuned. What happens when you have these fine misattunements is you get these frequencies that meet and give off all these vibrations, overtones, and new frequencies that erupt. Even if it is fifty notes, and three octaves, they are all in a different tuning and when they meet they create this friction. I also took the notes I created and manipulated into each of these movable forms. I changed the speed of the vibration, so it was shaped by how quickly the note reverberated.

As you can see, I’m really going into the material and treating musical notes as material. Each note is carefully created and then manipulated. Afterwards, I layer them and compose them together. You can hear this piece on the record and you can also see these two projections in these two projections on the wall. They are still part of the piece and part of them will be in the daylight, so they kind of disappear into the light in a mystical way.

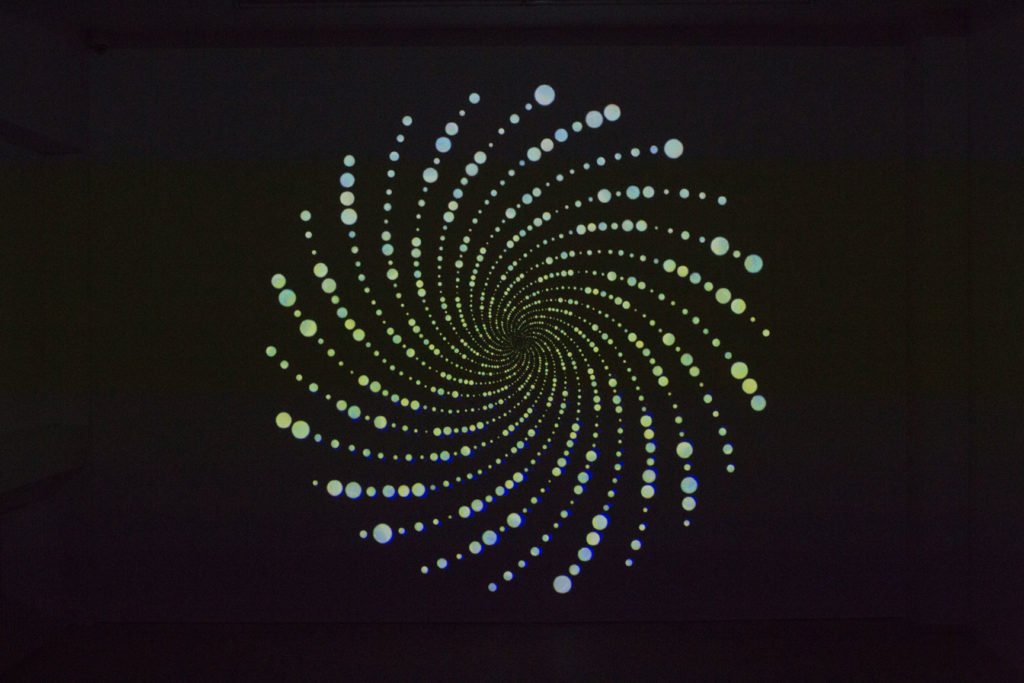

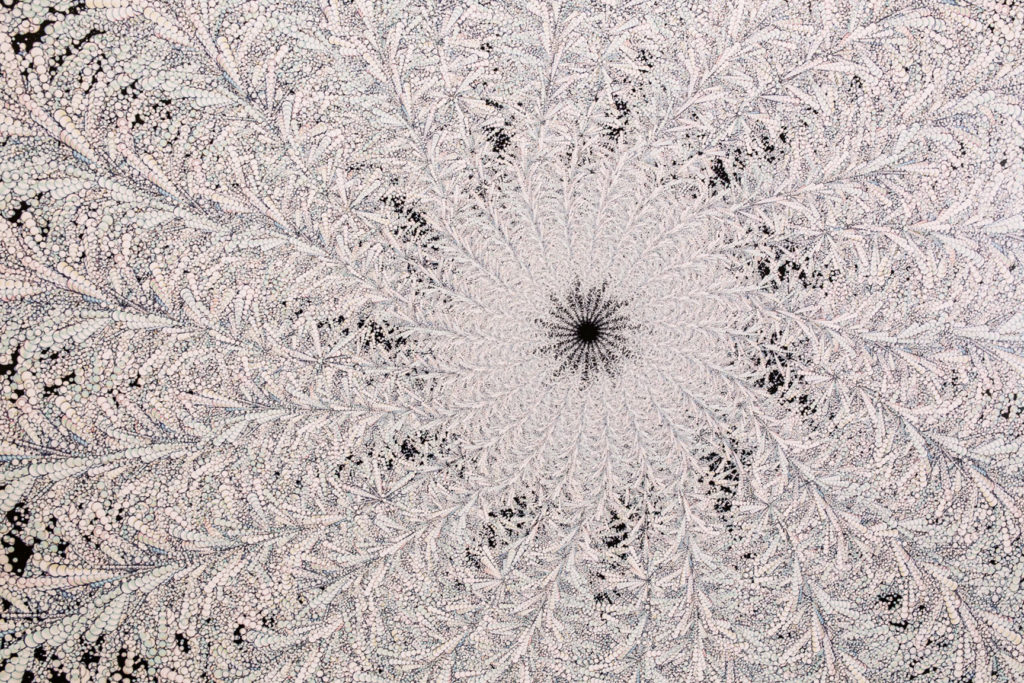

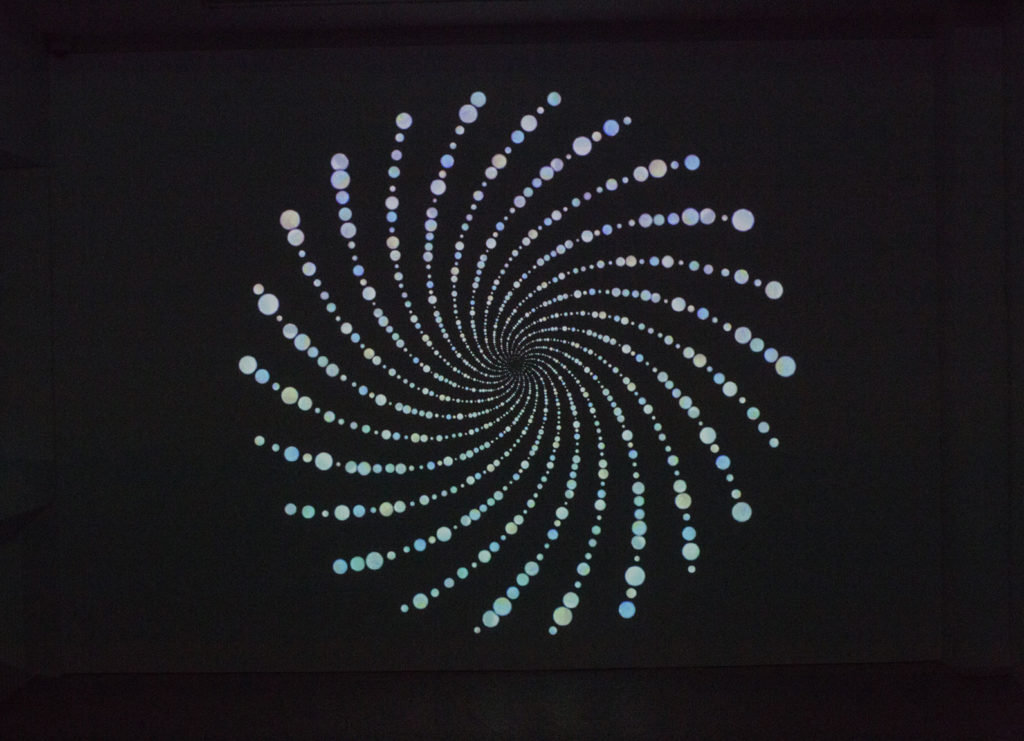

Erin: Can you explain this visual (the animated projection in C Series) a bit and how it correlates to your vertical investigations?

Dodda: So the music is a vertical investigation and that’s the translation from lyrical film where I’ve been working in video with this vertical investigation with video that I’ve been applying to music as well. This piece is the one I made after the composition was finished and is actually a result from starting DeCore and investigating proportions, going into geometry, and alchemist’s graphs. This is actually created from an alchemist’s graph and shows an Egyptian energy key. I don’t make my work after other images, though, I have three works where I’m working with alchemists’ graphs. Usually, I never use outside material but I was just interested in these geometric images that have this visual energy to them. There is some message being told and I’m not exactly interested in finding out what it is supposed to tell me but I’m interested in the energy of them. That is why I wanted to assimilate it into my own process.

Erin: The name of it even, ‘alchemist’s graph’, sounds like a parallel investigation to the work you’re doing. What an alchemist does is tries to transmute gold out of these chemical elements.

Dodda: But it’s all symbolic in the end. When they’re talking about gold they’re actually trying to find spiritual gold. It’s spiritual, not material. Alchemist’s search for gold was sacred knowledge.

Erin: Even that transition between material and spiritual knowledge and matter is like a parallel investigation to what you’re doing.

Dodda: Especially in this one because I’m working with the base material in C Series which is actually these 3D computer generated spheres. I basically took snapshots of 3d images and took them through a very 2d way of working, almost to this old school level of animation. So I’m working with this artificial form to create this alchemist’s key. To me, it feels like energy plugged into this loop. It also reminds me of the music symbol where you have an F key or G key and you ascribe a key to your composition.

I’m also breaking a lot of musicology rules here by playing with terminology and using it inaccurately on purpose. The tradition is such a long one and can be quite fixed, so it is perhaps good to playfully skew it a little. I also did this with Études by really playing with the terminology. We’ll be releasing a record on the opening, a limited edition vinyl of 30 editions that will also be on Spotify. I’ve been working with music for such a long time and it has been such a nice experience, materializing these prints, so releasing the prints and materials and music as materials is quite exciting.

Erin: You’re working in such an immaterial realm, so I can imagine it is exciting to have such a material outcome in an exhibition.

Dodda: It’s a new development in my work for sure. Here are the different forms of the notes for C Series, screened as just a small projection in the exhibition. I find the musical compositions much more interesting than the visuals actually. The original animation I made doesn’t add anything to the composition so when I’m working with video and music together there always has to be a purpose. If there is no reason I usually take it out as I would rather have silent videos or stand alone sound pieces. You can see this is just how a material note might materialize. I’m just opening up ideas of what music might be. This almost could be presented as a sound piece as I’m working with sound ideas even though it is silent.

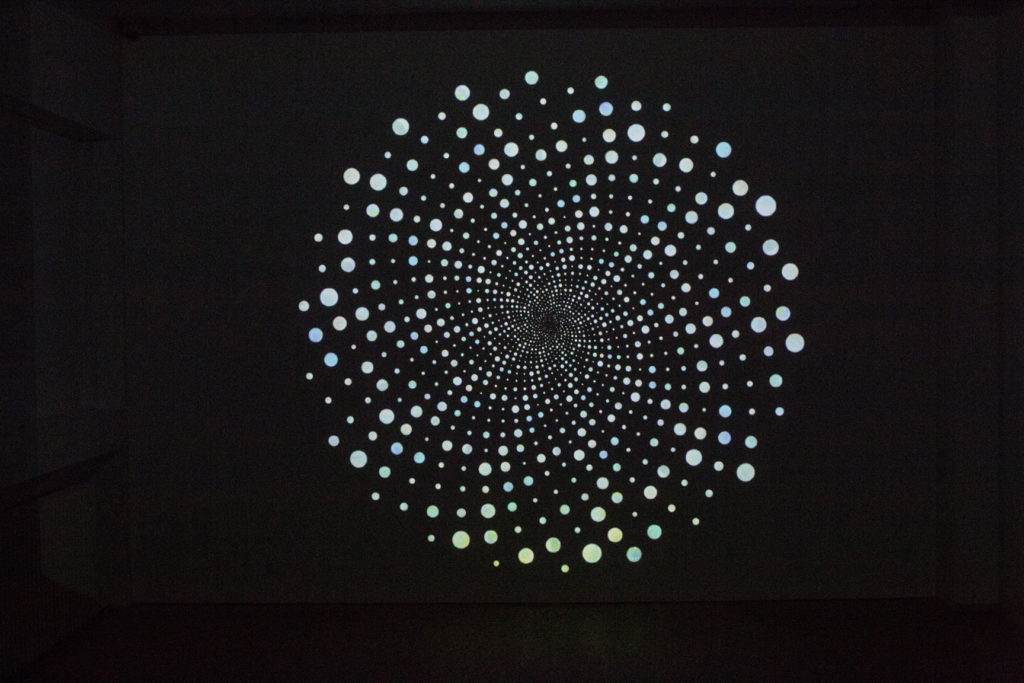

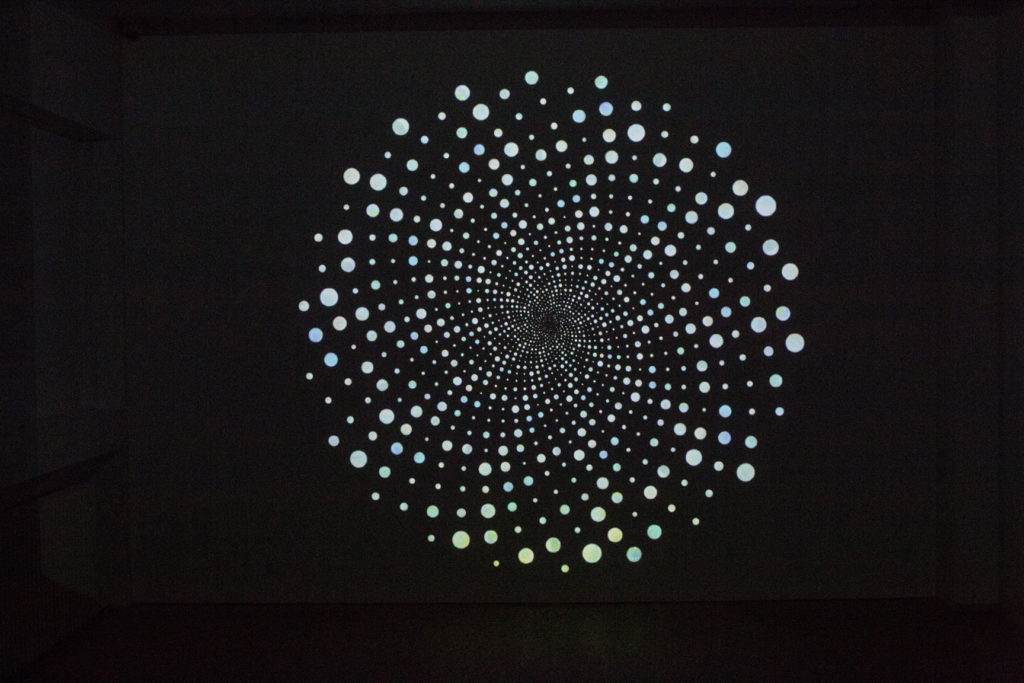

Erin: This is a similar shape to the Mandelbrot set, a fractal named after the mathematician. Anytime you zoom in or out into one specific part you come out eventually into the same shape for infinity.

Dodda: You can find it in nature and in the cosmos. The environment is just the basic building block of everything around this fractal relationship. Even in these snapshots of planets of stars, it’s always fractals. Even the path Venus moves around the sun is a fractal. It makes one wonder how everything is connected to these forms.

Erin: You can look at your work very formally. You don’t have to go there, but it’s laid out for you if you want to, however you can also just recognize the mathematical and musical harmony in the formalities.

Dodda: If people are interested in certain subject matters they pick it up or they don’t. There are different perspectives of looking at my work- very formal, very sensorial, and sometimes working with more mystical ideas. I’m always questioning and never offering answers.

Erin: You’re still very technical in your mystical notions, which is a beautiful combination.

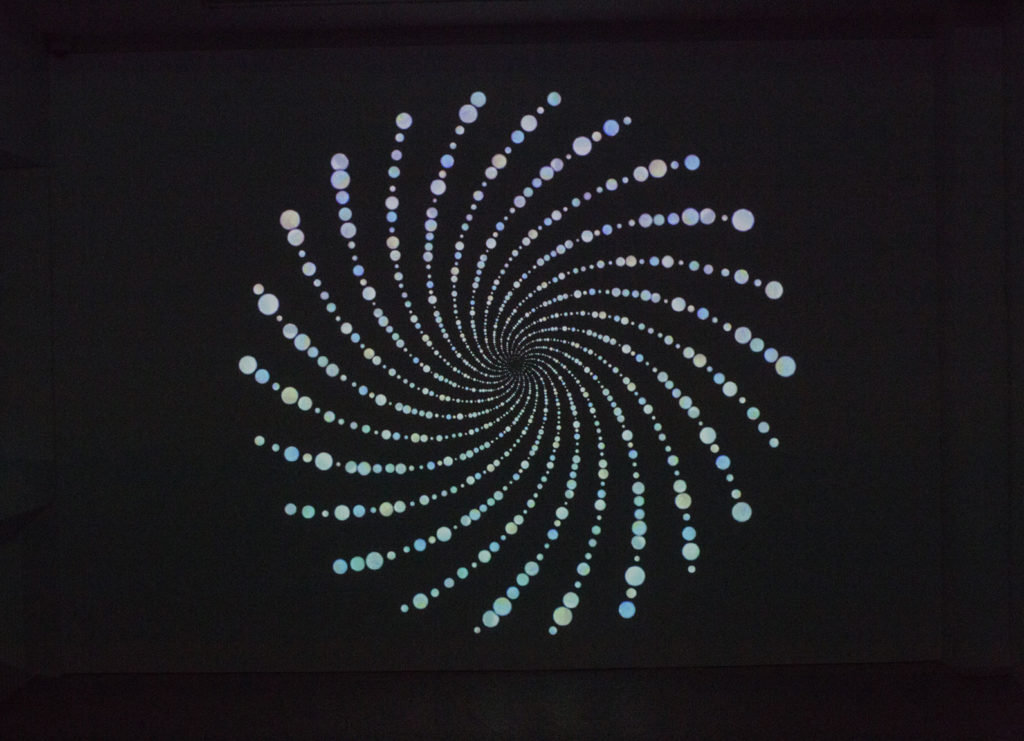

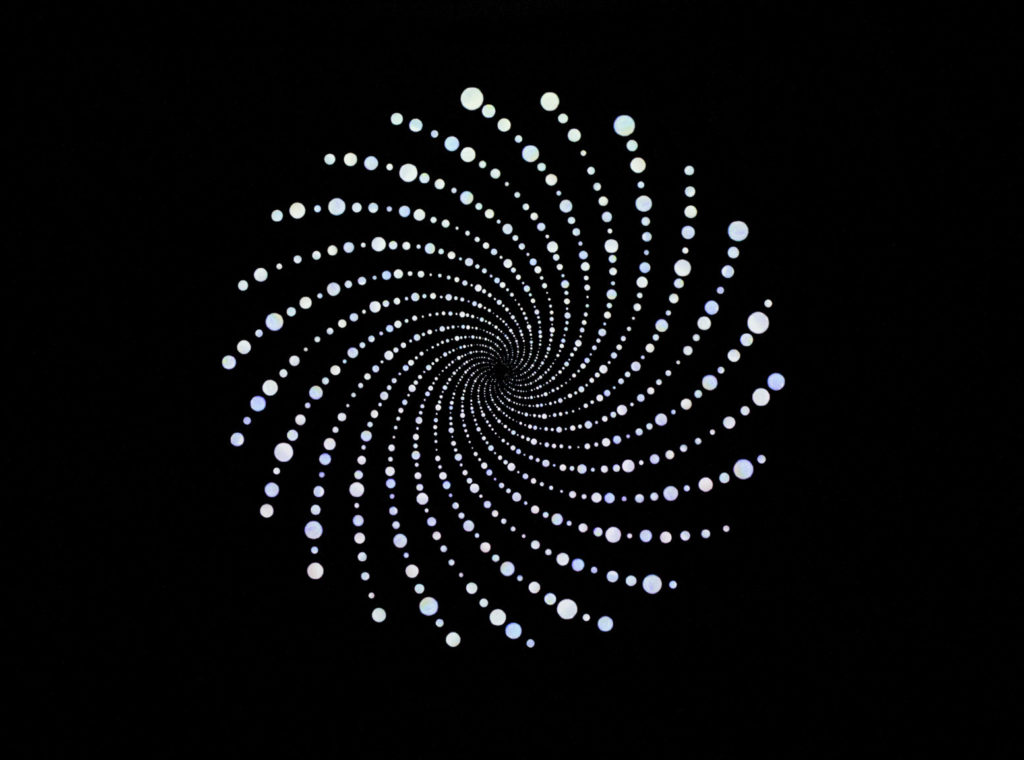

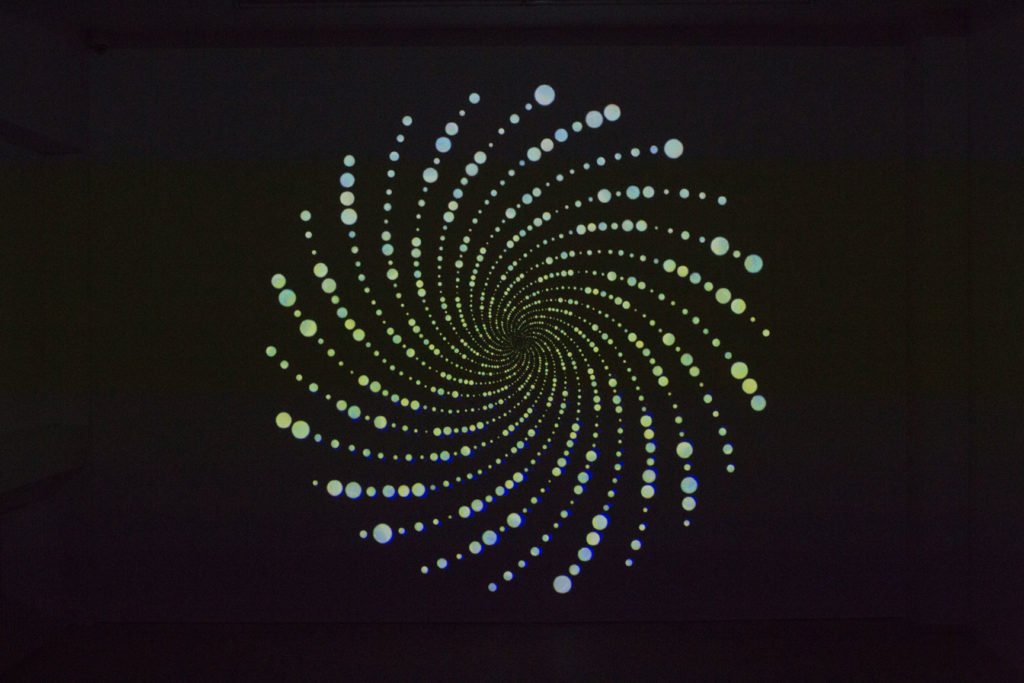

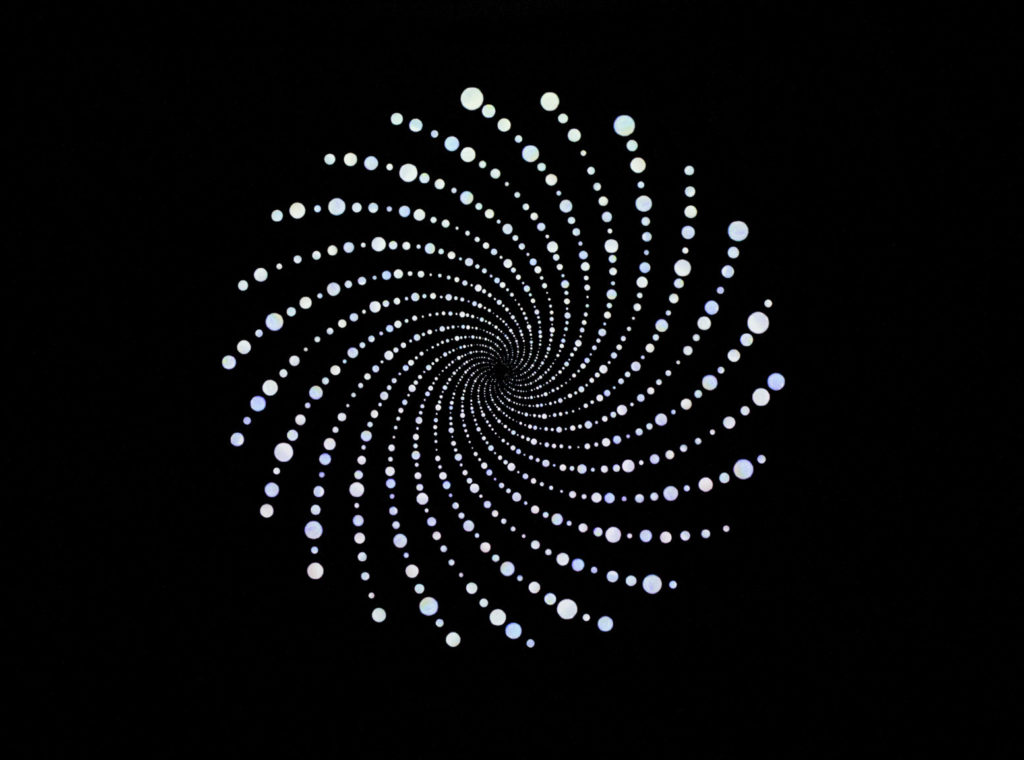

Dodda: The last part of the exhibition is called Étude for which the basic building blocks are these Opal forms. There are different investigations into visual music which started in the 1910s and 20s by visual artists trying to find ways of composing music visually. It’s hard to define as a genre because it crosses all these styles between animation and structural film, but the umbrella term is ‘visual music’ which began in Europe and was developed later in California. One experimental filmmaker, in particular, was intriguing for me, John Whitney. He regarded himself as a composer but his instrument was the camera. He spent his career trying to develop ways of translating visuals into music. So I was quite inspired by his technique and wanted to experiment with his technique to apply it to my own experimentation. So I’m not duplicating but I am interested in how he structures entities together in a visual. I think there is definitely a visual reference to his work in Étude. Étude pays a little bit of an homage to him in the name Étude, which is usually a musical composition that a skilled composer creates for his student to practice. I’m using it as an exercise for practicing visual music.

I want to make a visual music piece in this tradition and so I regard this as my practice piece in visual music with a certain methodology. I’m also making a wordplay between the use of “Opus” in music which stands for the “work number” and is written as Op. In Étude, Op. stands for the number of opal stones, so the first piece is actually 88 Op. I’m also examining the piano in particular by working with 88 stones which represent the 88 notes of the piano.

In the Étude series of prints, you can see the full 88 notes, as well as compositions with 22, 33, 44, 55, 66, and 77. So I’m making up these rules, imagining how to materialize chords into a visual. I created these seven structures that are in the composition and I these as my elements in the installation. So this is a very formal piece but the idea actually came from a dream. In the dream, somebody took me up to the cosmos into black space and showed me opals growing in the darkness. I was being told that they have energy and frequency. So I was quite intrigued by these stones mined from the earth that have a measurable frequency. So even if it was a dream, it is still quite formal, personal, yet very formal. I was also interested in working with the relationship between the visual and the sonic/aural/musical in this piece and exploring perceptual experiences involved in translating internal experiences into the external to represent different states of consciousness.

Erin: This cultural critic named Gene Youngblood wrote a book in the 70’s called Expanded Cinema about how all of these expansive techniques in film have been parallel with the expansion of consciousness.

Dodda: Compared to where video was in 2000, you had to have a video camera and know how to use it, but today it’s totally part of our daily life. It’s so interesting how video is the same material as our memory, like our current state of consciousness.

Erin Honecutt

More information about the artist: www.doddamaggy.info

Ljósmyndir: Daníel Magnússon.

Photo: Vigfús Birgisson

Photo: Vigfús Birgisson

Photo: Daníel Magnússon

Photo: Daníel Magnússon