Last Saturday I attended the inaugural Plan B Art Festival in Borgarnes, a town just an hour’s drive north of Reykjavík. It was a free event, organized by a group of artists, an art theorist, and an architect, many of them hailing from Borgarnes. The festival was arranged through an open call for submissions which ran earlier this year, from April to July. The exhibition spaces were filled with paintings, sculptures, videos, and installations, while the fourth space, Studio Mjólk, was a venue for a few works and performances on Saturday night. A foggy day filled with structured gallery hopping in the city ended with an emotional spasm when I completely gave myself up to the performances at Studio Mjólk—they each demanded a different type of mental effort and level of concentration to process and understand. In case you didn’t make the performances on Saturday night, I’ve got you covered: this is a short summary of my thoughts.

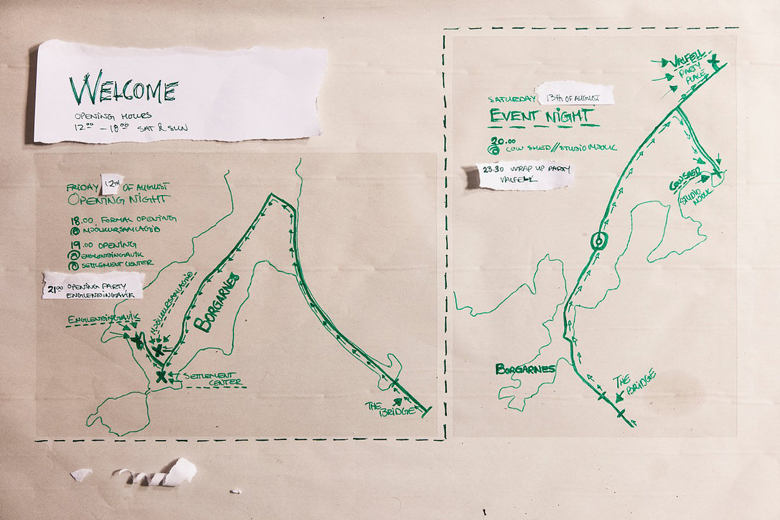

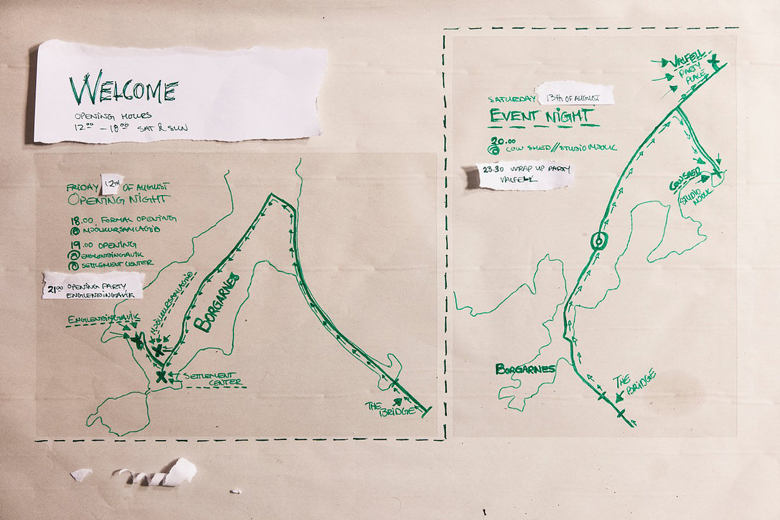

First, in order to get to the performance venue from downtown Borgarnes, you had to hop into a car and follow a treasure map that was drawn up for the event. If you scanned your eyes to the right side of the map, you would have found a large X surrounded by three arrows, labeled COW SHED. Yes, indeed, Studio Mjólk was located on a farm but the space, entirely cleaned up and converted, fit the performances perfectly.

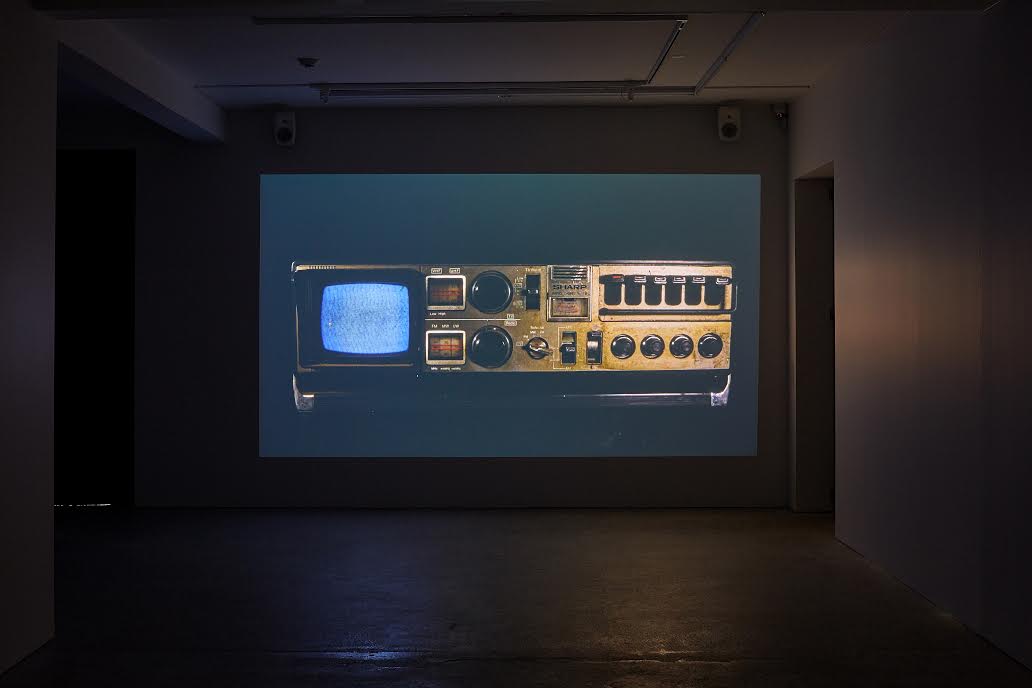

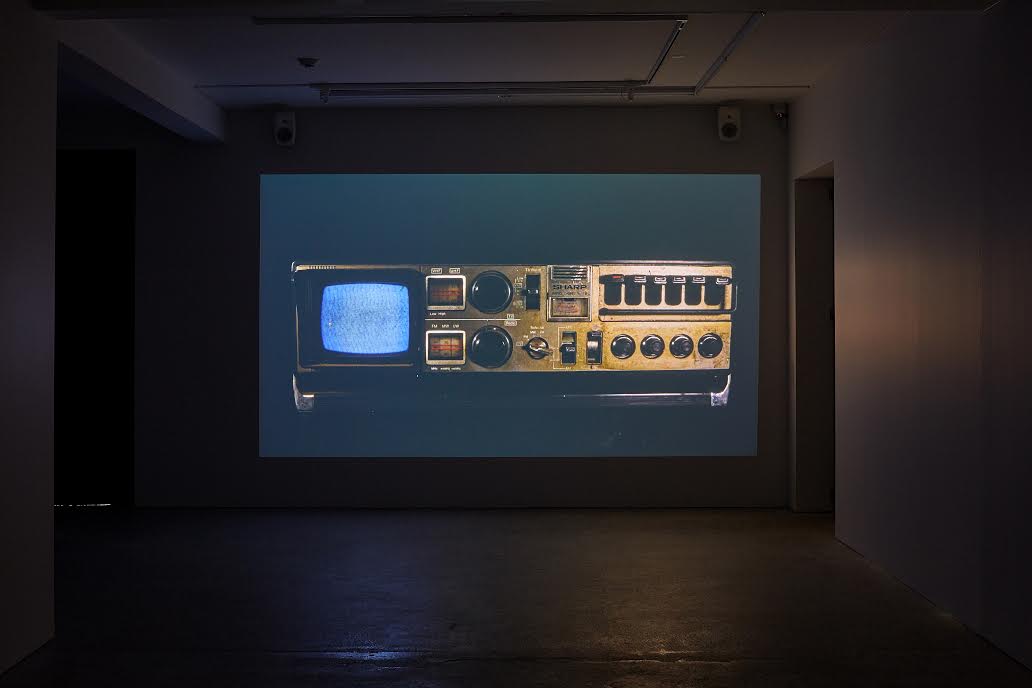

The night began in the first part of the shed, where digital projections were displayed around the room, showcasing the works of Harpa Einars and Jakob Veigar. In the back of the room, artist Maiken Stær was unsuspectingly reclining in a hay filled stable as an early part of her performance “strap-on butterfly.” After 8 pm, more visitors filled the barn and grabbed a beer. (See image on top of article)

A voice then emanated from a speaker and announced to us that we were being invited, or possibly being summoned, into the following room. I heard banging and clanging from behind the interior double doors, and a bright red light shined through the crack in between them. After the first two audience members abandoned the comfort of the beer and projection room, and left the rest of us standing in the dark, we quickly decided to follow suit and entered the performance space: an industrial environment flooded with bright spotlights and bits and pieces of used metal. “This feels like a dungeon,” I remember thinking, and in my head I knew we were all going to be in for a surprise. I had just entered Olga Szymula’s installation but had not anticipated to become a part of it along with the rest of the audience. What ensued was a brilliant ensemble of aluminum-foil-rattling, horseshoe-banging, hand-holding, circle-walking, and balloon-kicking, in a dark room in an empty cowshed in the middle of nowhere. We began to hum a song together, led by Olga, who walked around in the center of the room with a microphone in her hand, encouraging us to hum a certain way. When the room was completely filled with “uhms” and “ahms,” and when we were all holding hands, walking around in a circle, I felt that each of us in the room and even the baby being pushed in the stroller had become a family. That baby became my baby. Olga became my sister. I loved every minute of the performance and I want to relive it every week for the rest of my life.

Olga performing “national song.” Photograph courtesy of the author.

Some time later, a naked boy emerged crouching on the floor by the far wall of the room, surrounded by computer monitors on red cloth-draped pedestals. We curiously huddled around him. He looked like a beautiful kinetic statue in that moment, demanding attention to his softly lit body in the the dim room. He then stood up and perched himself atop the concrete floor with a bowed head and his arms at his side. This was Anton Logi Olafsson’s performance entitled “ROOSTING.” He reached for a pair of shorts on the ground, and before I knew it, he was leaving the room and heading out of the shed. I headed for the door as well, entranced, confused, fascinated. I felt his adrenaline pass itself onto me, and I wanted to run away with him. But I never did, and I never caught up to him, because he headed down the road and ran away from the shed and the farm. I don’t know what happened to him. Anton, are you okay? I thought about what he could be running away from so determinedly, and I feel that his instinct to run away from a technologically reliant enclosure and into an open, natural space is one we could all relate to.

The next performance was a continuation of “strap-on butterfly.” I was suddenly standing in front of a girl with her wrists chained to her body, positioned in front of an industrial white double sink, and she was diligently pouring water from one sink to the other. The lighting in the shed was haunting and dramatic. The sinks rapidly but rhythmically dripped water from their bottoms. Maiken wore a lopapeysa with no sleeves, and her entire body glimmered as it reflected the only two lights in the dark room. An unexpected whale vertebra became the center of her attention and she eventually abandoned the sinks, but the interplay between these objects was flawless—Maiken’s body connected them and brought them to life while the rest of us watched with curiosity and unpredictability. Crouching on the floor, she began to cradle the large vertebra, and this intimate dialogue between the two actively progressed as she went on to wrap her chains around the bone, rode it, caressed it, and worshipped its presence.

Emma Guðnason brought the laughter to the evening with her performance “shitcore; a loud statement against all wars!!!” Clad in an eclectic homemade costume with a cape made of Bónus and Krónan shopping bags, an aluminum foil cap, and a toothbrush attached to her forehead, Emma revealed a complex relationship with a metal sheet and an amplifier, generating chaotic but epic sound clashes through the whole performance. Frustrated but actively moving around the littered paper on the floor, Emma revealed a sign and taped it to the wall – the title of the performance. The pink pigs on Emma’s cape occupied my vision as I listened to the persistent clanging of the metal sheet, and I was then transported to a reality of bizarre, but here in the shed, totally normal happenings. Energy and angry emotions filled my own body while I watched Emma, whose performance motivated me to think about our members of humanity who continue to fight for our freedom of speech and expression, freedom to react and to protest, and freedom to fight for peace in the midst of “all wars.”

The only appropriate ending to the night had to be epic and highly intensive, and Ylfa Þöll Ólafsdóttir’s performance did not disappoint. Ylfa pulled into the barn shed in her small car, parked it, and darted out of the vehicle. Wearing a car mechanic’s outfit, she opened the doors and trunk of the car and hopped onto the roof. A deep, primal roar came out of her throat: “DAME MAS GASOLINA.” She would continue to demand more gasoline as she assumed various positions both inside and outside of the car and, ahem, – humped—the car. Fast and furious, potentially painful, and completely serious, it was difficult to look away. Her moans and groans, and the frequent repetition of “dame mas gasolina” penetrated every corner of the shed. The emergency lights on the car blinked, the windshield spray shot out and away from the car in a completely sexual way, and Ylfa continued pounding the car for the entire length of the performance. No door or seat was safe from her hips. At one point, she smeared what looked to be car oil on her face, and the act quite visibly satisfied her. I imagined the type of response the car would had given if it could have given one—was this rape or was this consensual? Ylfa’s costume filled in the gaps for me. A hilarious situation came to life before my eyes—a desperate, gasless car mechanic, with no physical gas around, took a final attempt to revive the car and exhausted herself in the process. When Ylfa finished, she shut the gas tank, the doors, and trunk, got into the driver’s seat, miraculously turned on the car, and backed out of the shed to a clapping frenzy from the audience. It must have worked. While I was watching Ylfa I was also scanning the room, looking at the faces of the audience. Some were at total peace, their faces completely neutral, while others were entirely giddy with laughter. Even some children were watching. Ylfa’s performance challenged me to accept her behavior. I tried to identify what it was about the performance that initially disturbed me. Was it her seriousness, or perhaps the sound of the satisfaction in her voice? I was caught off guard and without an explanation. Thinking about the act of putting gas in a car, I realized that the gas pump is entirely phallic and the act of putting it into a hole in the car really emphasizes this analogy. When the performance ended, I was relieved in the sense that I finally understood Ylfa’s efforts—she fueled up the car by fully committing her body to the cause. I think we all walked away a little bit changed by “Gasoline,” and maybe quite relieved that we actually put gas in our cars in a less demanding way. I would have enjoyed a Puerto-Rican ready made cocktail as a mid-performance refreshment.

Ylfa performing “Gasoline.” Photograph courtesy of Gissur Pálsson.

If you missed Plan B Art Festival this year, do not worry, because it will be back to Borgarnes next summer. You can still view works that are up at Mjólkursamlagið, the venue on Skúlagata, as it will run its exhibition through August 27th. However, an entire set of artworks were not covered by this review, but you can read about the full selection of artists who participated and find more information on their work at www.planbartfestival.is. The weekend proved to be a fantastic engagement with the Icelandic community, but the festival also brought international artists to Iceland and even provided some of them with a residency studio leading up to the date of the festival. You can read more about Plan B Art Festival, and stay up-to-date with news, access more photos, and hear about the next open call applications by following their Facebook page: facebook.com/planbartfestival. If this first festival is any indication of the festival’s projection, I say come prepared to be completely unprepared for the newest, weirdest, coolest art being made in Iceland and internationally.

Anna Toptchi is an art history graduate student living and writing in New York City.

My background is primarily in theatre, although my work is quite interdisciplinary by nature. So I’ve ended up working in other art forms too – I’ve made films and done a bit of performance art. I just like to make work by whatever means is necessary for telling the story, so that can include any relevant medium. Although theatre is certainly my home, I trained classically as an actor.

My background is primarily in theatre, although my work is quite interdisciplinary by nature. So I’ve ended up working in other art forms too – I’ve made films and done a bit of performance art. I just like to make work by whatever means is necessary for telling the story, so that can include any relevant medium. Although theatre is certainly my home, I trained classically as an actor.