They want to murder the patriarchy -Sita Valrún and Bergrún Anna tell us about Murder Magazine

They want to murder the patriarchy -Sita Valrún and Bergrún Anna tell us about Murder Magazine

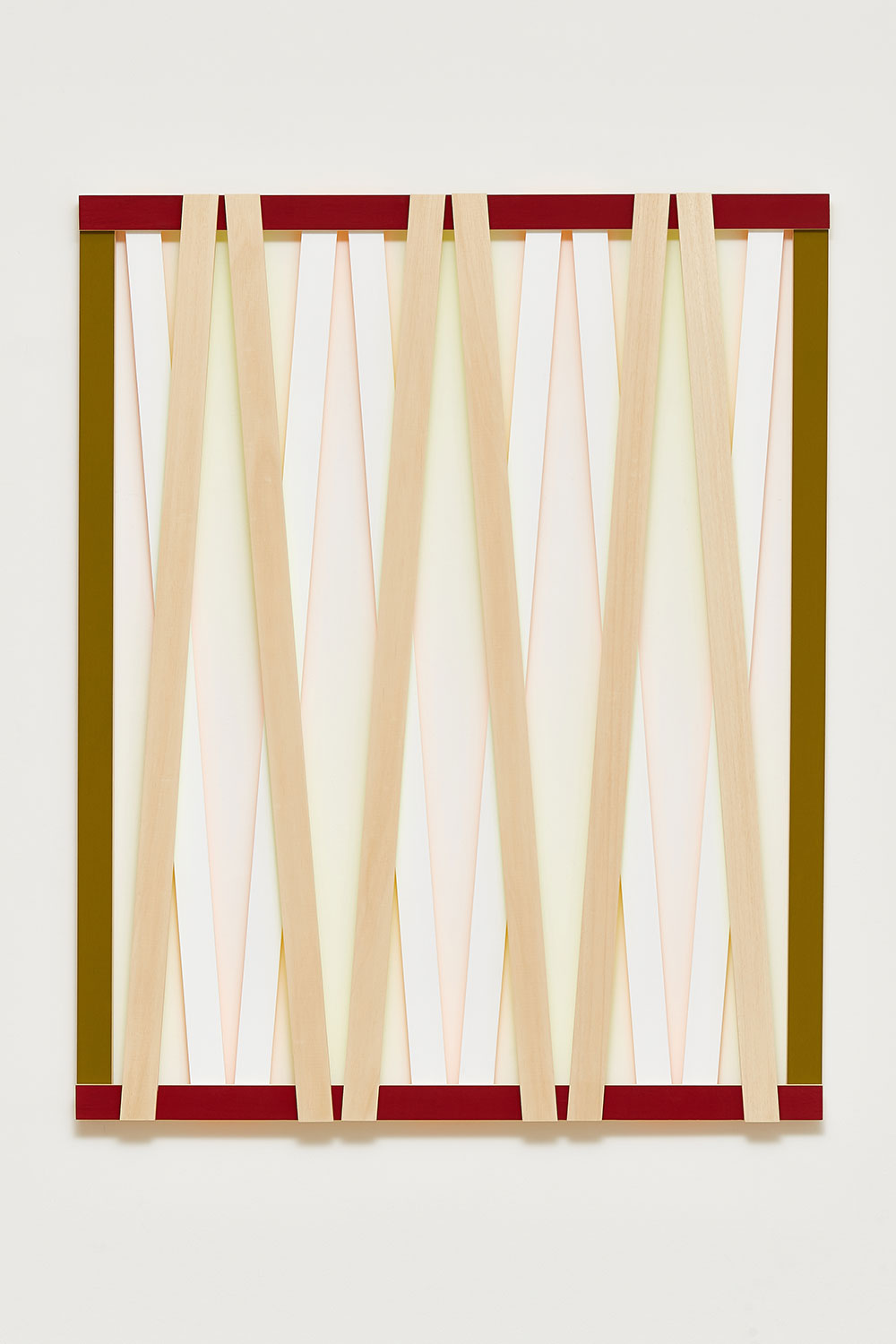

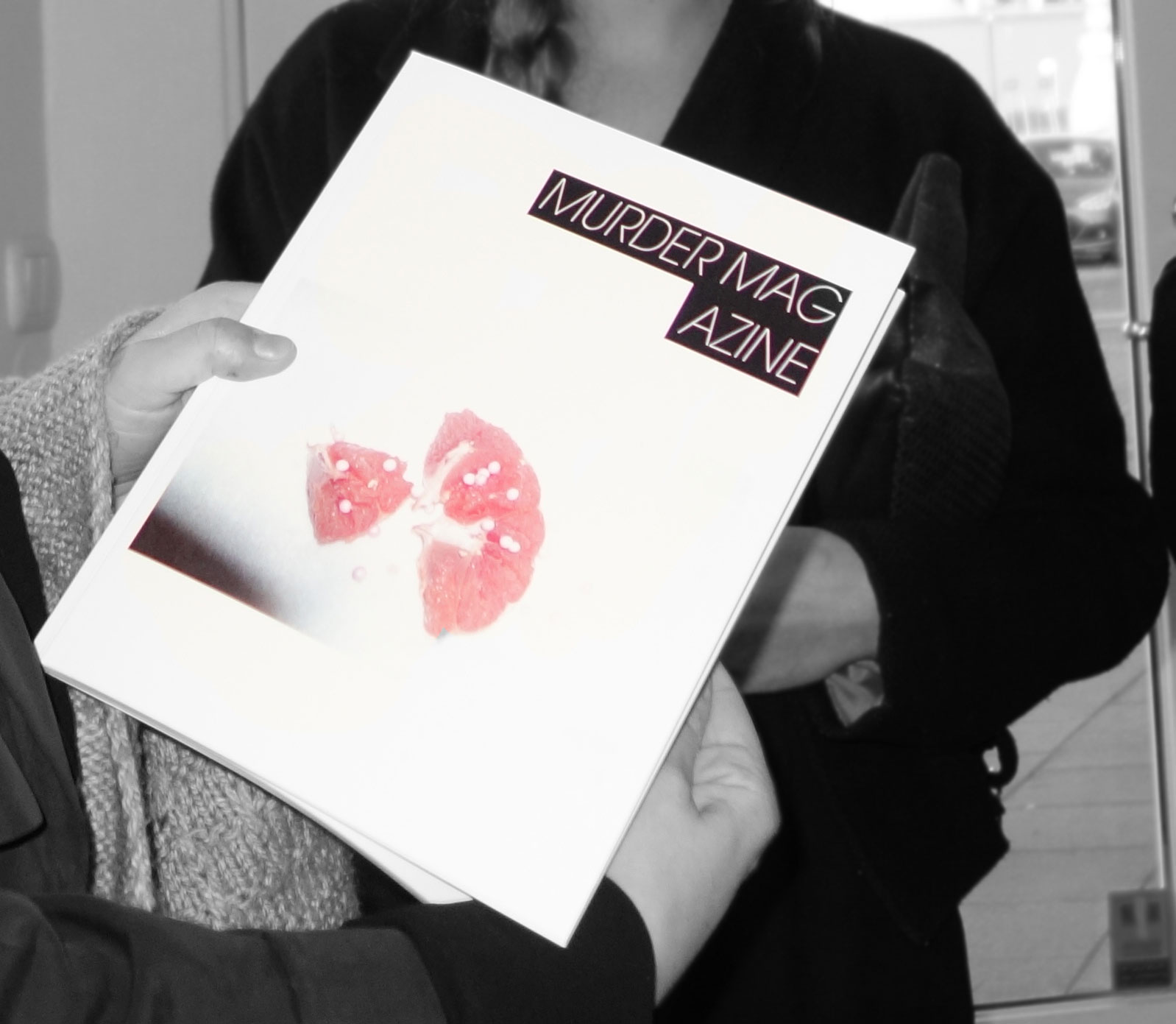

The first edition of Murder Magazine was published in May 2017. The editors/curators are writer/artist collaborators Bergrún Anna Hallsteinsdóttir and Síta Valrún. The magazine will have a different theme for each edition which will be published every three months. The theme for the first edition is ‘Body/Invisible’. I asked the creators a few questions about their new artistic platform.

Erin: When I Google ‘Murder Magazine Iceland’ the first things that come up are about the death of the young woman in Reykjavík earlier this year. I began to think about her story, walking home from a night out alone, and how it fit so well with the contents of this first issue of the magazine. It could almost be a tribute of sorts: the ultimate ‘Body/Invisible’. Did you come up with the name before or after this tragedy?

Síta/Bergrún: It’s interesting because the name came at the very start. At that point, we were in a very punk feminist vibe and the choice to use murder magazine came as part of that. The idea was that we wanted to murder the patriarchy 😀 since then we developed and de-labeled, cleaned up the aesthetic but we kept the original idea, we still want to murder the patriarchy but we want it to be an action, however small or large it ends up being. Not something we announce, but something we do. We did have a conversation about the murder here, earlier this year… it’s definitely sensitive. And we thought now when you described that it could even seem like a tribute, that this was very beautifully put. It’s not a tribute to her consciously but it’s a tribute to the invisibility of women and therefore, very much to those women who are murdered by men. The inclusion of ‘fanmail’ to Ana Mendieta is definitely a part of that tribute. In the end though, we are aiming to address the oppression of women, both by publishing primarily women, and also choosing material like “alchemy of pain”…well, all of it actually, where women are able to describe their experiences on their own terms and in their own words, or visually.

Erin: Can you tell me the brief story of how Murder Magazine came about? Your initial ideas, inspirations, visions, etc.

Síta/Bergrún: The story of how the project came about is kind of funny. We wanted to hold an exhibition together, so we would meet up to plan it. The conversation would somehow move in the direction of feminism and we would end up just sitting there, really pissed at the world and so we never managed to plan the exhibition. Then we had a break and came back to it with the idea of a newsletter instead of an exhibition, but then we were moved to make something tactile first, something which people could hold onto, and feel the weight of, so the idea of a zine which was more like a magazine in appearance and quality came about. Something where we could maintain our independent thought, but which would be a publication that people would value and take seriously. Not just a crazy rant, as it could be. Also, very important was to create something beautiful, a piece which people would enjoy owning, rather than being something that would end in the trash.

Erin: What can an artistic platform in the form of a magazine (or is it a zine?) offer that other mediums cannot?

Síta/Bergrún: The thing that attracted us to the form of the magazine is its compact nature which lends itself well to sharing. It’s moveable. Basically, it’s a Mary Poppins exhibition space, where people can put it in their bag but it can contain the whole world. We also liked the idea of being able to easily show art and poems we liked ourselves, without logistical difficulties. We made an open call, sent out fliers through friends in different countries; Mexico, Australia, New Zealand, America and various European countries and it was great to be able to make something so big and so small. We also contacted artists that we admired or if we thought that they would fit.

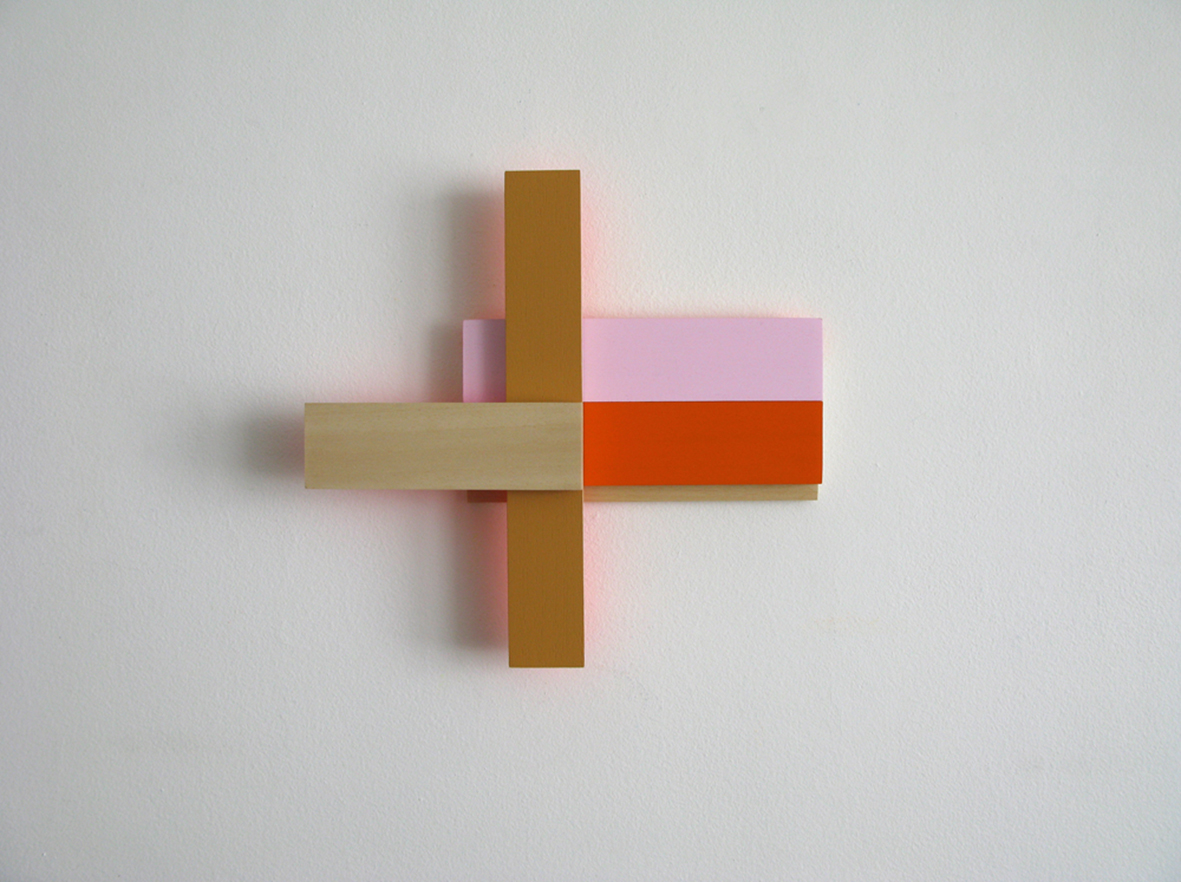

Erin: The theme for your first issue, ‘Body/Invisible’, brought about visuals and poems that are distinctly feminine… Do you have an outcome in mind when you decide your themes?

Síta/Bergrún: With the theme we did chose particular works so it was steered in that way. However, the majority of the work shown is the contributors’ interpretation of the theme ‘body/invisible’. This created an interesting outcome and was fun to curate with, working with knowns/unknowns. So yes, the feminine aspect could be due to many things. The fact that it is mainly women whose work we showed. The fact that we are women, choosing the work. The theme of body/invisible is perhaps also leading. The dichotomy of man/woman, mind/body leaves women very often connected to physicality and bodily-ness, so the connection of women to the body in a sense leads to this erasure… if that makes any sense? It does to us at least.

Erin: After being with the magazine in its entirety for the first time, I was struck by notions of pain and beauty. Do you think this came about from the theme of Body/Invisible as well?

Síta/Bergrún: Pain and beauty. We definitely see a clear red thread of pain and beauty running through it all. Which is in a sense also connected to that erasure. Like we were writing in the editor’s note, somehow we have to be hyper-visible, but not exist at the same time. Beauty is such a complex phenomenon, a much-used word which we feel entails so often making oneself vulnerable, in a myriad of ways. And that is painful.

Murder Magazine will be available in Mál og Menning, Listasafn Reykjavíkur-Hafnarhús, and Kiosk.

Erin Honeycutt

Photography: H.G.Ó.