The Importance of ‘What If?’

The Importance of ‘What If?’

Kwitcherbellíakin at Reykjavik Art Museum.

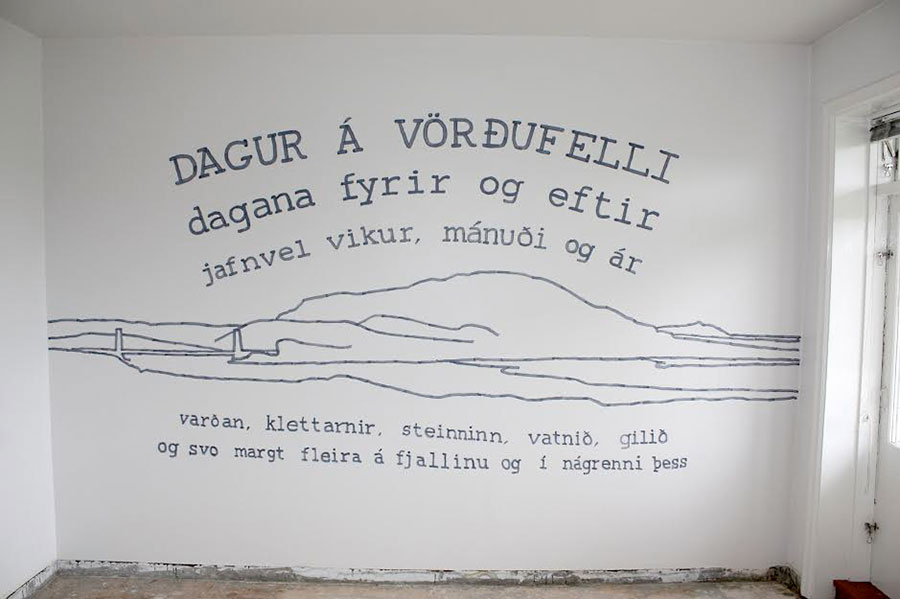

The two week installation Kwitcherbellíakin ended the last weekend of October at Reykjavik Art Museum as part of the Occupational Hazard project, a think tank which evolved around the former United States Naval air base, Ásbru. In the project, the former NATO-base plays a role as both a geographical place as well as a rhetorical meeting place where local Iceland meets global affairs. The site has now been reinvented as Ásbru Enterprise Park, a business development center for science, education and innovation. As Ásbrú is a poetic term (from the Snorra Edda) to describe the rainbow bridge leading to the home of the gods, it is a fitting description of the transitive identity of the place as a means to another place. The Occupational Hazard project focuses on the use of speculative fiction to rework past narratives and imagine future scenarios and conditions of being. A place such as this acts as a non-place in which to both rely on as a structure and to formulate the breaking of that structure through imaginative speculation.

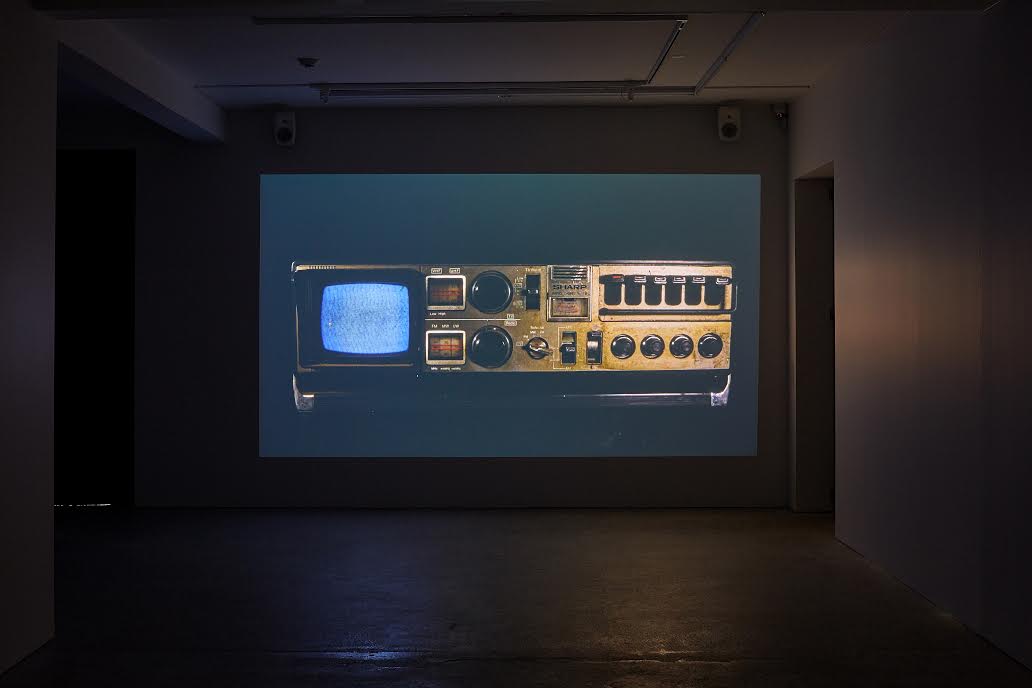

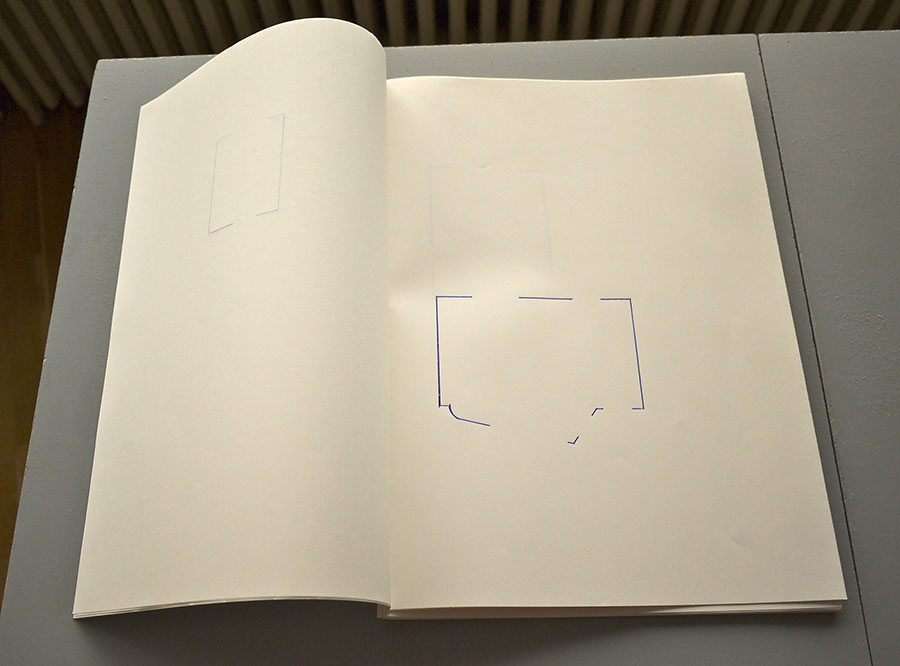

In the installation put together by Hannes Lárusson, Tinna Grétarsdottir, and Ásmundur Ásmundsson, we see an amalgamation of Land Art and Glitch Art meeting cultural detritus. Other artists collaborating in the installation were Pia Lindman, Unnar Örn Auðarson Jónsson, Skark and Ato Malinda/The Many Headed Hydra. The digital collages within the installation contained historical events, icons, and innuendos mixed with a wide sweep of Western Art historical iconography. The symbology juxtaposed with historical imagery spoke of the contemporaneity of the situation as the historical events’ power and influence was still as much a part of the current dialogue.

I continually returned to Foucault’s notion of heterotopias when attempting to unpack the layers of meaning involved in the installation and its context within the wider speculative project. Foucault’s heterotopia is one in which the suspension of time and place holds infinite possibilities of past and future. His account of institutions of power produce a contrasting space in which several incompatible spatial elements are juxtaposed in the same plane of possibility, encapsulating discontinuities. Time becomes weightless in the heterotopian conditions. Embracing seemingly everything but art, the installation makes an account of the condition of being spliced between neoliberal ideologies and capitalist junctures. Aesthetic engagement can bring a more sophisticated take on the reality which we are grappling with.

No title, 2016 (Ásmundur Ásmundsson, Hannes Lárusson og Tinna Grétarsdóttir)

In 2011, the artists created the controversial exhibition Koddu which highlighted political and socio-cultural changes taking place in Iceland since the 1990s. Their aim was to thread the relations between iconography and ideology in contemporary Iceland before and after the financial crisis and to address core ideas of national identity. In their analysis of Icelandic cultural politics, they brought into discussion some of the ways in which artists are used in the redefining of Icelandic culture to suit the needs of corporate branding, which can lead to a distortion of reality. In Kwitcherbellíakin, the artists continue to explore these themes in the direction of a model which aggravates the focus on utilitarian outcomes of art.

In conversation with Tinna and Hannes after the closing of the installation, we spoke further about their intentions, inspirations, and the processing of reactions. Hannes spoke about how the installation openly addressed elements that continue to play themselves out in the arts, such as the local/global interaction, which, according to the artist, is a continuation of the agenda that began with Iceland’s independence from Denmark in 1944. World War II not only marks the turning point in the history of Iceland toward modernization; the blast of the atom bomb in 1945 marks the beginning of the Anthropocene. As Tinna pointed out, “the promises of the ‘good life’ of modern progress has turned into times characterized by precarity. It is not just the soil that is exhausted – the social structures and human rights that are supposed to secure human and non-human well-being are increasingly dysfunctional and ignored.”

The installation was a camp in many ways, something which Tinna brings to the wider sociol-political sphere in noting how the term has been used to characterize today’s socio-political developments. The notion of the camp has been described by the philosopher Giorgio Agamben as “the fundamental biopolitical paradigm of the Modern” (see Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life). The sociologist Pascal Gielen uses the term to describe the art world and the false sense of freedom that it evokes, as the encampment of the art world is continually defined by the inevitable enclosures of capitalism. Tinna notes how Kwitcherbellíakin was the name of a camp in Reykjavík whose commander planted two palm trees and gave it this name. Other camps had very different names after generals or military history. As stated in the introductory text, it could be seen as the first art installation in Iceland, and the first contribution to the local scene.

Image: Kwitcherbellíakin, Reykjavik Art Museum (Court yard). Ingvar Högni Ragnarsson.

The ‘camp’ composed in the installation consists of a variety of elements each carrying a plethora of messages with which to assimilate into a consensus, but perhaps the heterotopic nature is best put into context here where the aesthetic statement is one of disjunction, certainly not an easily quantified outcome. The scale of the installation is immense for a two week time frame: 81 pieces of cloth painted as a rainbow by asylum seekers at Ásbrú during a separate project (the Broken Rainbow Project) hang on the railing amongst pieces of “trash” (none of which is made locally), 15 enlarged digital collages held up by 20 used Lazyboy recliner chairs resting on 40 tonnes of soil. There was also sound installations, videos, a diesel electricity generator, freezers, a compound microscope for viewing the tardigrade – one of countless organisms living in the soil, and three tonnes of stones from the demolished turf house, Litlabrekka.

Tinna described the reactions to the role of the soil in the exhibition space and how reactions to it were a case in point:

„While entering the exhibition space the audience becomes part of the installation. They need to find their feet to move around in the space ‘wearing’ blue plastic shoe covers – a telling image of our relationship with the soil and non-humans others. The 400 square meter exhibition’s soil-covered floor seemed to irritate many of the museum staff – they saw it as creating mess, infecting other spaces of the museum etc. Children were the most enthusiastic about the soil – curious and relating to it and its inhabitants. Soil is not simply a base of life. It is a world of relationality – a ‘multispecies muddle’ to use the words of Donna Haraway. The urgency of our times has called for reconfiguration of how to live with the planet and its inhabitants. Moreover, understanding the multiple temporalities of soil, its organisms and ecological assemblages might prove valuable to disrupt and resist the Modern progress of the anthropocentric, capitalist timescale.“

No title, 2016 (Ásmundur Ásmundsson, Hannes Lárusson og Tinna Grétarsdóttir)

While all of the digital collages in the installation are untitled and meant to be seen as a continuous iconography, it is possible to look at them individually. This image is meant to mark the beginning of the worldview that began with independence from Denmark in 1944. World War II was taking place at the time, a fact that the artists feel the impact of which is missing from historical narratives. In using speculation about the past the artists have the ability to bring up discussions about the commonly held narrative that has not been very present in public discourse. In the image are references to these global affairs such as the Russian tank and the American pin-up postcards on the table where the document is being signed. The absence of women at the signing is notable, although one of the men wears a woman’s hat from the Icelandic national costume. As the image tries to contextualize the place of Iceland in world affairs at the time, the dire situation is painted with humor. According to Hannes, “Iceland is always in dialogue with colonization, something which is not from Iceland, but the rest of the world. Even in current affairs,” he says, “the idea of maintaining independence while taking part in the global economy is a constant struggle.”

Images: No title, 2016 (Ásmundur Ásmundsson, Hannes Lárusson og Tinna Grétarsdóttir)

The frivolity which has marked the media sensation of the US presidential elections can be seen in these two images representing the dichotomy that has become the figures of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. Their respective icons have become synonymous with certain ideologies mashed together to create their monstrously heavy identities. The exhibition was held at the same time as the Icelandic elections with the US elections on the horizon; a precarious temporality, which in hind-site seems worlds away. The condition of time in the camp of the exhibition is effectively multilayered to address this sensation.

Like figures from the collective subconscious, they are composed from an array of sources that the viewer may not take into consideration consciously. The Medusa from Caravaggio is wearing a skirt from Degas that covers the tail from Nina Sæmundsson’s mermaid sculpture. Her outstretched arm is holding the balls of David from Michelangelo. Tinna notes that the male anatomy here is more like a handbag, which poses the question of how we are going to inherit this history: “…what kind of luggage are we going to bring with us into the future?” Thinking about future speculations and what kind of future we have ahead of us, this is why the Medusa is so important in this image. She pops up and has been used in philosophy and cultural discourse throughout history. As the original ‘nasty woman’ she has been brought up in the US elections as an allegory for Hillary Clinton. There are again many narratives to choose from. Tinna notes that these two images “…are not just the state of mind, the state of the world, or the state of art, but the state of the post-human…” The amalgamated figures are barely human, a branded interspecies pair who de-center the human from the Anthropocene.

No title, 2016 (Ásmundur Ásmundsson, Hannes Lárusson og Tinna Grétarsdóttir)

The Anthropocene, the epochal term that is marked by significant human impact on the earth’s systems, plays a large part in the exhibition. Covering a very broad timeline and embracing many system’s processes, it gives us glimpses of the role of speculation and imagination as a powerful tool in coming to realize the tensions inherent in any narrative. This embrace can allow a consideration of a wide spectrum of potential futures. To answer one of Tinna’s questions, “What can artists do in this system?” I think a potential answer is to continue wielding a way of thinking and creating that pushes the boundaries of our imagination where systems of oppression and fear would have us encapsulated by small-mindedness. We can turn judgment into curiosity and use fear to rouse empathy. In continuing to let “What if?” permeate our convictions and narratives, a plethora of possibilities and perspectives is opened. As political dichotomies seem to be approaching radical opposition in many places in the world, the need to break out of this binary thinking seems more important than ever. Speculative tools, as these artists have shown, can lead to different realities, some more dystopian than others, but it is the ability to be adaptable and authentic in our thinking that could make all the difference.

Erin Honeycutt

Featured Image, overview of courtyard: Ingvar Högni Ragnarsson

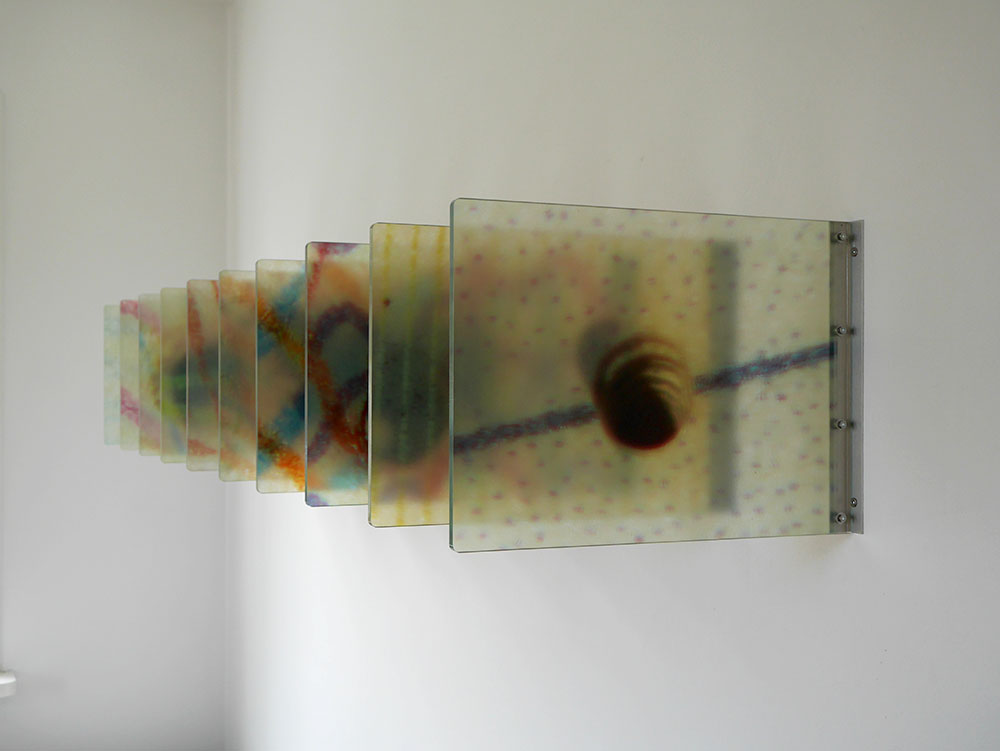

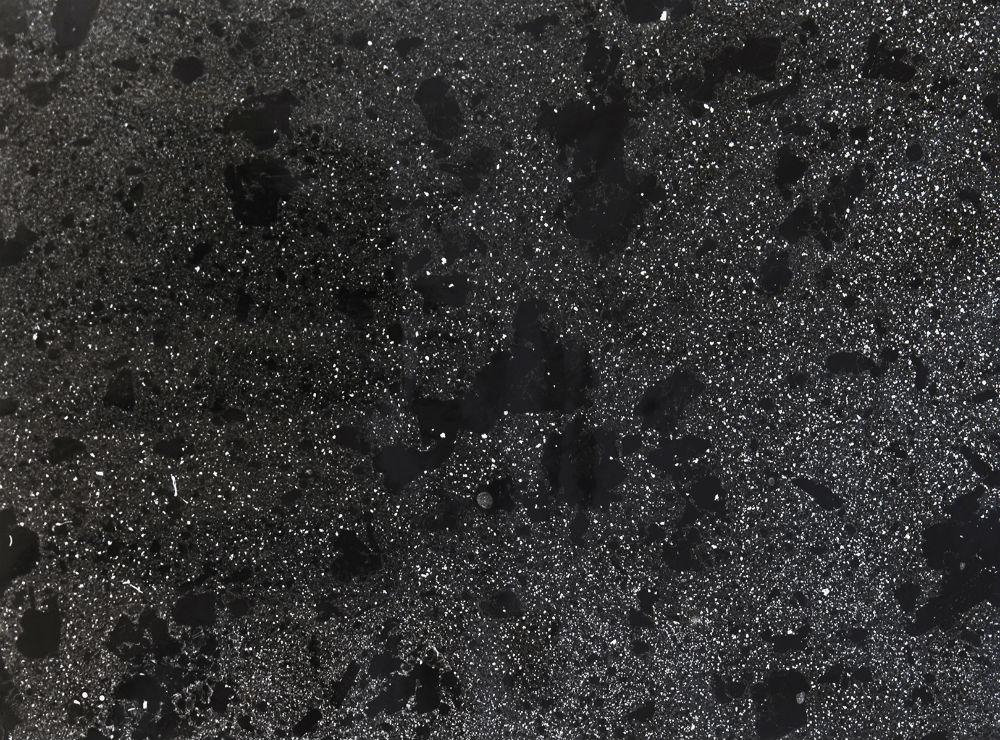

Detail of Hraun (2016)

Detail of Hraun (2016) Hraun (2016) No. 6281 and 6285, Gelatin silver print, 100 x 150 cm, Rock type: Gabbro xenoliths from silicic tuff, Place: Kambsfjall, Króksfjördur, Vestfirdir, Iceland, Age: 10 million years old, Petrographic slides borrowed from the Icelandic Institute of Natural History

Hraun (2016) No. 6281 and 6285, Gelatin silver print, 100 x 150 cm, Rock type: Gabbro xenoliths from silicic tuff, Place: Kambsfjall, Króksfjördur, Vestfirdir, Iceland, Age: 10 million years old, Petrographic slides borrowed from the Icelandic Institute of Natural History Holuhraun lava field

Holuhraun lava field Geologist Morten Riishuus and microbiologist Anu Hynninen at work

Geologist Morten Riishuus and microbiologist Anu Hynninen at work Geologic tool

Geologic tool Víti Crater

Víti Crater Lava from Holuhraun eruption

Lava from Holuhraun eruption