Hreinn Friðfinnsson’s assistants on the outside looking in (from the inside)

Hreinn Friðfinnsson’s assistants on the outside looking in (from the inside)

Recently on view at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin from September 28th, 2019 to January 5, 2020, was a retrospective of Hreinn Friðfinnsson’s work To Catch a Fish with a Song: 1964 – Today. It was organized in partnership with Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève where the exhibition was on view from 24 May – 25 August, 2019, coinciding with a new book on the artist’s career launched in Geneva and Berlin.

Befitting the intricate storylines of Hreinn Friðfinsson’s work, which often contain notions of time interwoven with revelation and concealment, I decided to talk to three of his current and former assistants about the artist instead of taking the usual research routes into the gathering information. I realized while walking around the exhibition To Catch A Fish With Song at KW that, although I had been writing about Icelandic art for a few years now and had even interned at his gallery, I8, in Reykjavik, for a year, the artist had somehow slipped from my focus.

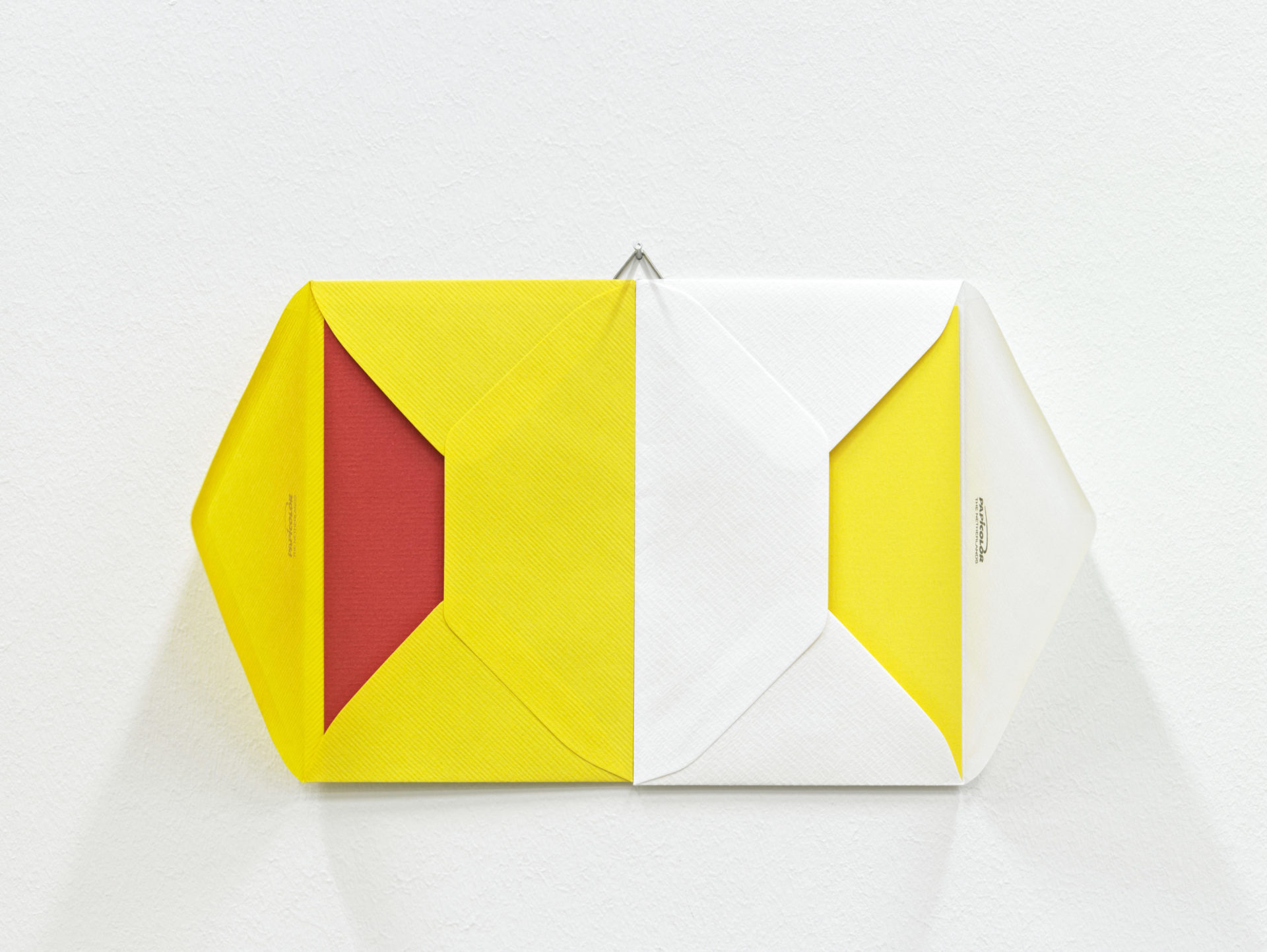

Hreinn Friðfinnsson Correspondence, 1991-2014 envelopes, paper 14 x 18.2 cm. Courtesy of i8 Gallery.

Hreinn Friðfinnsson Correspondence, 1991-2014 envelopes, paper 14 x 18.2 cm. Courtesy of i8 Gallery.

An opportunity to study his work closely never arrived, and perhaps, I never felt the push as he is such a mythological figure in the Icelandic art world, like a godfather of Conceptual art in Iceland. He is often mentioned in context with the brothers Sigurður and Kristján Guðmundsson of his generation, who studied in Holland in the 1970’s and returned to Iceland, mixing the international modes of conceptual art with a distinctly poetic Icelandic gesture, really using our connotations with words as a work in itself in this fluid play with words. I always got this sense that there was a level of respect that you just have for the Eddas and poetry in general when you grow up in Iceland. I always thought about these old stories about how poets in the Sagas didn’t use swords or, but if you wanted to fight you would have a battle with words as though they were real physical weapons themselves. What these magic words are I have often thought about, especially in making a connection to a specifically Icelandic style of conceptual art.

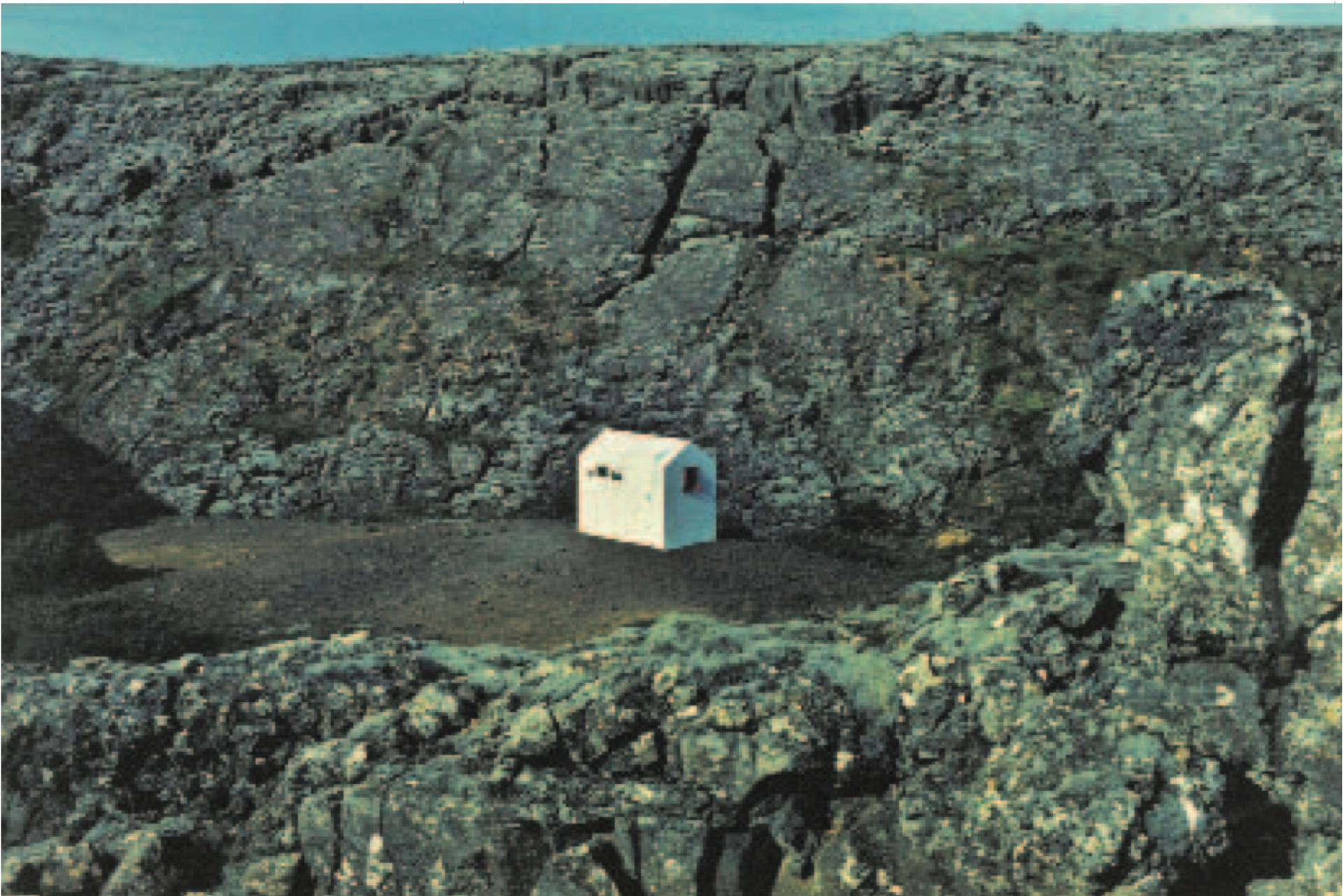

Hreinn Friðfinnsson House Project, First House, 1974 Mixed media. Courtesy of i8 Gallery.

Hreinn Friðfinnsson House Project, First House, 1974 Mixed media. Courtesy of i8 Gallery.

Perhaps I never wanted to penetrate the elusive figure of Hreinn and rather wanted to keep him in this lofty and unreachable place of inexplicable poetry that was somehow tied into a tradition of poetry that the language just oozes, in the way it adjusts to situations and objects, like a phenomenological lens of the world in itself. This is very much an outsider of the language looking in, although I speak it enough to get by, but not with an inner sense for the language. I don’t have a feel for words. This was the golden halo I had wrapped Hreinn inside, faithful to the truth or not, at least it was conceptual. I was familiar with Hreinn through the exhibition and book called Homecomings edited by Annabelle von Girsewald and Cassandra Edlefsen Lasch, which looked at Georges Perec’s Espèces d’espaces (Species of Spaces, 1974) in the context of Hreinn’s House Project which also launched in 1974. In talking to his assistants, I saw the form of my gaining knowledge of the artist as being akin to this most sustaining narrative work of his career, the House Project (1974 – ), which began as a gesture that would successively take many different forms.

“In the summer of 1974, a small house was built in the same fashion as Sólon Guðmundsson intended to do about half a century ago, that is to say, an inside-out house. It was completed on the 21st of July. It is situated in an unpopulated area of Iceland, and in a place from which no other man-made objects can be seen. The existence of this house means that ‘outside’ has shrunk to the size of a closed space formed by the walls and the roof of the house. The rest has become ‘inside’. The house harbors the whole world except itself.” (1 Hreinn Friðfinnsson, House Project: First House, Second House, Third House (Crymogea, Reykjavík, 2012).)

Hreinn Friðfinnsson House Project, Third House, 2011 stainless steel 64.027060, -22.070652. Courtesy of i8 Gallery.

Hreinn Friðfinnsson House Project, Third House, 2011 stainless steel 64.027060, -22.070652. Courtesy of i8 Gallery.

Sólon, to add another layer to the project, is a character set in 1912 in the novel ‘Íslenskur aðall,’ (“Icelandic Aristocracy,” published in 1938 by Þórbergur Þórðarsson. Using the story of Sólon, the artist made an inquiry into the boundaries of space, an inquiry that has continued to unfold in different iterations. The work continuously shapes to its environment through dematerializing by making an inversion of the surroundings or by mirroring them. In my conversations with his assistants, their perspectives of the artist become a metaphorical practice in the exterior of the house of Sólon looking in at the character of the artist known as Hreinn Friðfinnsson. His assistants are the outside looking in (from the inside).

Styrmir Örn Guðmundsson, former assistant

Hreinn is on the phone with the whole world. He just sits at home and calls whoever he’s working with. When he’s producing work or a show, I feel like he is a puppet master.

Or maybe it’s better to put it this way: he will get an idea that has something to do with astrophysics, let’s say, and then he’ll call an astrophysicist in Iceland that he knows and asks him how something works and why some object is turning like that. And then he’ll get an idea for something physical so he calls a carpenter in The Netherlands and starts building something, and then calls the assistants, and then he calls the gallery. He calls a hundred times in one day and then everything sort of falls into place. I’ve always been very fascinated by his way of working. I think it is interesting that he isn’t working in the studio himself but he makes these correspondences, directing this whole process of conceptual art production.

At the end of the day, it is all Hreinn. That’s the fascinating thing is that he is so brilliant at capturing ideas that otherwise would just fly by. Often people all around him are, in a way, reflecting on something that he’s talking about and then this idea of a work comes into the open. He’s really good at capturing these ideas going on on the telephone, calling immediately the next day someone who starts working on it. So, what I meant to say is that I think there are a lot of people around him that play a big role in his way of making things that in the end, of course, are his creation. Even though he is a conceptual artist working with found things and readymades, there is still this Friðfinnsson style.

He is definitely a super storytelling artist and he uses text especially in his 1970’s work. It was really what he was busy with just combining text and images, but also Icelandic ghost stories, so he’s really a good example of an artist who is big with storytelling, even though later it is maybe less. His work is not literary, but when I am with him in his house, he is always making up stories, rhymes, even raps, especially after I was infecting him with my rap practice. He was immediately coming up with some rap lyrics because he comes from that old Icelandic tradition. So he has that really in him, deeply rooted, to make up rhymes and that’s really amazing.

I think Hreinn is a sorcerer at times in his works. He doesn’t know physics on an expert level but he uses it in this way that you describe that is like a kind of sorcery. He is even like a sorcerer in the way his phone conversations is him just picking up the phone, without even having an agenda, and he becomes like a bit-torrent that is just downloading as long as he’s reaching out to people. I imagine it’s like a remedy for any artist to just be active making phone calls and emails and slowly having everything assemble into a whole show.

HREINN FRIÐFINNSSON A View in A (1), 1976 black and white photograph 52.5 x 64.5 cm. Courtesy of i8 gallery.

HREINN FRIÐFINNSSON A View in A (1), 1976 black and white photograph 52.5 x 64.5 cm. Courtesy of i8 gallery.

Hrafnhildur Helgadóttir, current assistant

There is a word that kept coming up during the process of making the publication, which ended up not being in the publication, a word that was often used to describe Hreinn: Titlaflakk. Literally, titla (title) flakk (wanderer).

Being busy with the archive and the chronology of his work we were really going through his whole career, and for people who are working with the installation, we saw how some titles return again and again. In the 1980s, everything was untitled which was very popular then, but very annoying for registration.

For example, Above and Below hasn’t been with a title for ages until now. It’s almost like a work can be seen as being in process until the title comes. In the publication, you can even trace the title of the works and how they changed. For a lot of artists, this is part of their practice. It was nice to put it in the book as an official thing. Sometimes I’ll come to the studio and suddenly there is a title where there wasn’t one before. Sometimes just one word inside of a title has changed, such as ‘my’ sky or ‘your’ sky.

Also, all the people who work for him have nicknames for works as well. For example, a video work at KW made in 2018/2019 of Hreinn’s hand and a candle. Like many of his works, it is an illustration of scientific discovery. The staff nickname is ‘reaching out’ but the official title is: Reaching out: left-hand shadow sent on a journey to infinity through the window in the small room. Once you project the shadow in space there is nothing keeping it in the room…. It is on a trajectory to infinity. Words chosen have to carry the meaning. It took months to choose what the title was going to be and moving between English, Icelandic, and Dutch. It was almost like knitting.

The title of the show, How to Catch a Fish With a Song, comes from a series of text works by Hreinn called Clues because they are actually sentences taken from NY Times crossword puzzles. Hreinn doesn’t know the answer to the puzzle.

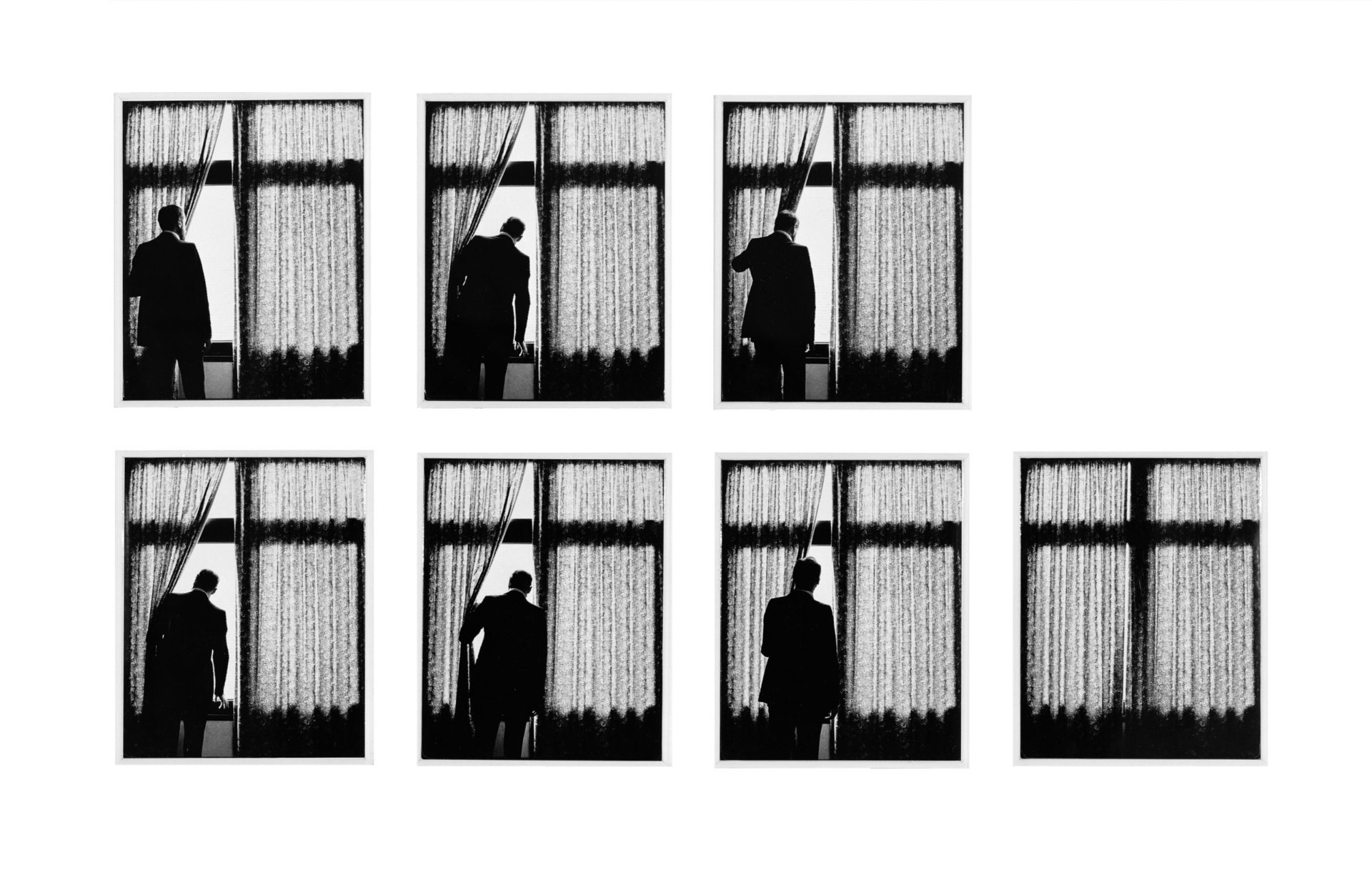

Hreinn Friðfinnsson Seven Times, 1979 seven black and white photographs each: 29,8 x 20,3 cm. Courtesy of i8 Gallery.

Hreinn Friðfinnsson Seven Times, 1979 seven black and white photographs each: 29,8 x 20,3 cm. Courtesy of i8 Gallery.

Halla Einarsdóttir, current assistant

He is fluid with words, but also a bit greedy. For example, if he liked a title he would put it on several things and as time went by he would neglect the fact that he had already used it. Greedy in a funny way, but at the same time very ready to cancel out the fact that he has already used it. He can also be controversial with himself which was a funny wall to hit constantly as we were gathering things for the publication. We came across the fact that he is writing his history with this book, so there is a constant struggle because with some works, which is also perfectly his decision, but works he didn’t like to take out of the canon but the editors liked it. So it was a constant back and forth process.

He basically had to trace his life from the 1960s, emotionally as well. It was amazing how much he remembers and is very quick to remember. It’s this self autobiographical work with the fence that began my archiving part. It’s basically that he walked, when he was 24 or 25, since he comes from the west of Iceland on a farm, for a summer job for two years where he was guiding a fence that had been set up because of the sheep disease. It was an insane distance, like 50 km every other day. He would walk one distance and his brothers would drive and pick him up. He made this work in 2014/15. I was reading these yearbooks from a newspaper around this area and from then on it escalated and I started to scan his archive which was loads of work. As Hrafnhildur probably mentioned, he hasn’t been consistently updating the archive. I picked up where Styrmir had made his own logic and it wasn’t until then that I realized how great it is to have many people in on the logic of organizing it.

Conclusion

Styrmir observes that Hreinn is on the phone with the whole world like a distant puppet master, or a „bit-torrent that is just downloading as long as he’s reaching out to people.“ Hrafnhildur observes Hreinn as being a ‘title wanderer’, never settling on a name for an artwork and letting it drift throughout his career, signifying his careful attention to words to specify artworks or to connect them to otherwise disparate works. Halla observes the importance of having many people involved in the logic of organizing an archive. Hreinn is writing his own history, being controversial with himself, writing his own history, being ‘greedy’ with words and wanting to use it everywhere. Hreinn’s assistants give us a different perspective on the artist, clues to the artist that are poetic, indirect, and perfectly befitting, just as the title for the show at KW was borrowed from a NY Times Crossword puzzle clue for which the answer is irrelevant. The clue to the answer contains all the poetry and points of departure needed, like a Koan for which there is no answer but the thought processes involved in trying to solve it are the answer itself.

Erin Honeycutt

Cover picture: Hreinn Friðfinnsson, House Project Fourth House, 2017, polished stainless steel, 255 x 325 x 195. Courtesy of i8 gallery.