The Fabric Created the Form: On Artistic Potentials Of Covering

Plastic animals

In september last year I saw a work at the Miró foundation in Barcelona that sparked my thinking about the act of covering, and its artistic potential. An installation by Gerard Ortín titled Reserva includes some fake, plastic animals that are manufactured as hunting dollies. The worn-out surfaces of these foamy creatures suggests a lived experience. They are placed in forests so that hunters can practice their skills on them, long before they approach real wildlife with real animals. Within the installation, the plastic animals are presented on a big screen, in their appointed role. Placed, standing still in a wild-life situation, they blend with the environment, immersed with their surroundings. Endured, still frames are presented to the viewer, giving her the time to actually find the subject hidden within the frame. Boars, bisons, mules, deers and other creatures imitate a natural setting, where the animals are frozen in place.

Each time an animal is found, the video cuts to the next frame, where the process of spotting may begin again, separating the subject from the background. Next to the screen, the foamy animals are exposed as what they are, piled together (physically) as plastic objects full of holes and wear from their days of being hunted over and over again. The dimly lit space blurs the boundaries of each body so they actively camouflage each other. Their collective shape remains a large, blurry, foggy, body of legs coming out here and there. These moments of revealing make it possible to identify animal from animal and manifest my initial interest in looking at the inherent duality of covering and revealing. In this way, going from representations on a screen and being superimposed in a space, the act of covering could be the participation in a collective body. A collective body which fluctuates in a dynamic consisting in constantly hiding something, and as a consequence, revealing something of it at the same time.

A blind tent, a camouflaged shelter made for photographers hiding in the woods (Stock photo)

A blind tent, a camouflaged shelter made for photographers hiding in the woods (Stock photo)

Artists are hunters in the many ways that they collect materials. Seen through the lens of mere commodities, these animals become figures in a constant limbo. That is to say, they continue to play dead even though they are to imitate the living. Immobile in the space they are presented in, the animals reflect the way humans have hunted for many, many years. Humans hunt with stillness as their weapon. Stealthy, sleek, and above all, hidden from the one who is being hunted. In the woods, camouflage patterns are worn by hunters to disguise them as their surroundings. Imitating the animals that have the color palette of the forests that engulf them. The environment covers, the animals are the covered, and humans have appropriated this fashion to their advantage.

Concealing coloration and the invention of camouflage

The modern understanding of camouflage can be traced back to the artist Abbott Thayer and his research in to the colors of the natural world.

“In natural camouflage, a wide range of animals benefit from an inverse coloration scheme. That is to say, their bellies are white or lightly colored while the color of their fur turns progressively darker as we scan towards the top of their body. 1”

Especially when still, animals can remain mostly undetected to the naked eye. Thayer did paintings and studies of natural inversions of color, proving that opaque, three dimensional objects can be flattened out and effaced in to their surroundings by light hitting their surface. Animals, naturally, become living optical illusions this way and other solid things too if shaded correctly. The contrast usually highlighted by the outlines of opaque objects breaks by nature’s ability to erase it. The things in the foreground start merging with the background.

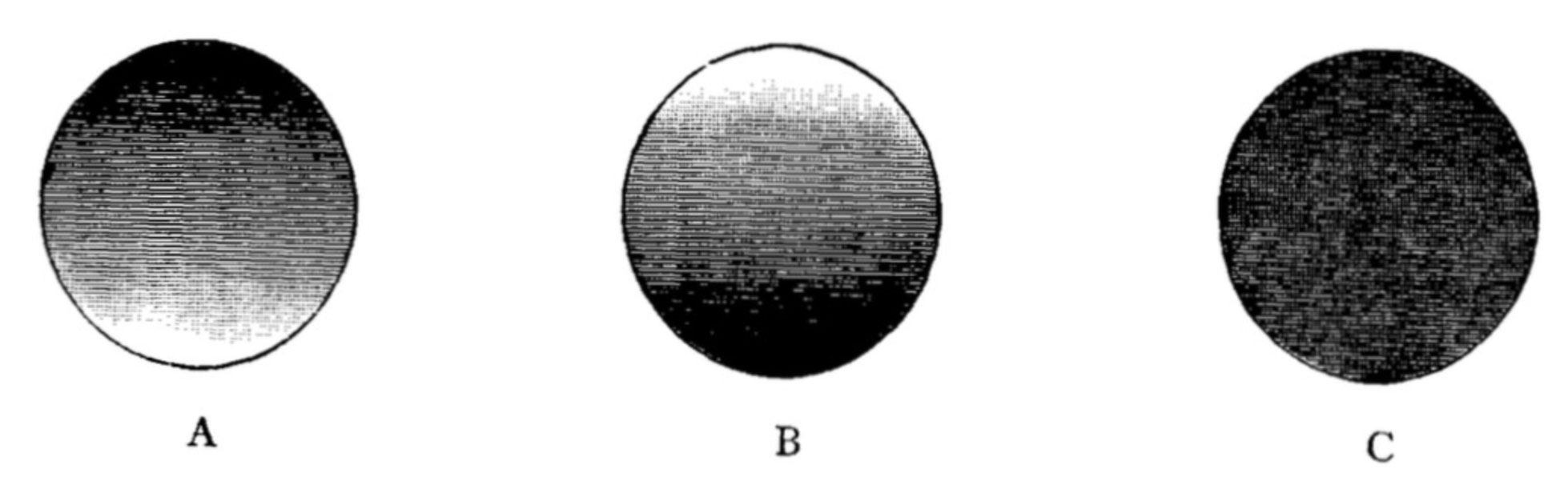

“Animals are colored by Nature as in A, the sky lights them as in B, and the two effects cancel each other, as in C. The result is that their gradation of light-and-shade, by which opaque solid objects manifest themselves to the eye, is effaced at every point, and the spectator seems to see right through the space really occupied by an opaque animal.” Illustration of the inverse coloration scheme from Abbott Thayer’s lushly illustrated “Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom” (original released in 1909).

“Animals are colored by Nature as in A, the sky lights them as in B, and the two effects cancel each other, as in C. The result is that their gradation of light-and-shade, by which opaque solid objects manifest themselves to the eye, is effaced at every point, and the spectator seems to see right through the space really occupied by an opaque animal.” Illustration of the inverse coloration scheme from Abbott Thayer’s lushly illustrated “Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom” (original released in 1909).

Thayer elaborates further on the two ways in which nature erases contrasts. One way is by blending. The natural coloration of birds, mammals, insects and reptiles mimics the creatures environment. The second way is by a disruption. Strong, elaborate patterns of color break outlines and flatten colors. So as to trick the mind by using a repetitive motif. This we are also familiar with in design, when we see a patterned surface and anticipate that its sameness will stay unchanged. In our anticipation we miss what might be lurking underneath the surface 2. Going back to Reserva, another film by Ortin shows a still shot of trees and bushes. It’s a bright day. The video-frame is perfectly still, almost like a photograph if it weren’t for a faint wind blowing through the branches. The visitor has time to absorb the scenery, as the wind synchronizes with the breath of the viewer, and the image evokes an uncanny presence. This is the presence of a figure that sits in the tree, right at the center of the frame. A spastic movement happens, a change in posture on top of the tree-branch. And from the moment we spot the figure, our gaze will not leave it. Let’s say that before we noticed, there was a pattern that covered the entire image-frame – a pattern of forest landscape. Like a design, the strong patterns of color flatten contrasts and break up outlines, so that the figure disappeared in to it or seemed to be something other than what it is. When the figure moves, a visual break occurs. We find something we can identify. The cover is blown by a sudden movement. To cover a person is to camouflage her. That person is not only hidden to the eye, but also, embodies the environment. Just like the bird blending in to branches of a tree.

Blending in

Harry Potter wearing his Cloak of Invisibility. A magical fabric produced to render anyone who wears it or whatever it covers invisible to the outside world. Screenshot taken from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Harry Potter wearing his Cloak of Invisibility. A magical fabric produced to render anyone who wears it or whatever it covers invisible to the outside world. Screenshot taken from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

In our day to day experiences, we often think to blend in, to act natural, to be as if not there. Covering is a way of becoming invisible, so in order to become visible, the question becomes; how do we break these flattening patterns? A body can be represented identical to a surrounding surface, but having a totally different essence. Let’s imagine ourselves as a fabric with such an intense and complex pattern that its appearances fluctuate as we move around. The fabric is capable of producing all kinds of gestures, creatures and figures. Our fabric is a make-shifter with countless possibilities and mirrors the way we are seen and see ourselves in the multitude of roles that the part-time worker (artist) has. Similarly to seeing an abstract silhouette in the dark. Each time you see it, it appears as something else compared to the night before. A fabric like that creates form and meaning as it moves and is watched. The forms in themselves formulating meaning after meaning after meaning. The inexhaustibility of the fabric’s surface as something not so different from the creativeness of shadow imagery or camouflage in itself. An inexhaustibility brought about by this game of hiding and revealing. I ́m talking about a flexible fabric that unfolds and generates meaning in a performative manner. In this way, and going from blending in, to cover can mean to become the other. The goal here is to obliterate fixated identities, which already shift around so much in our day to day experiences. With this fabric, we gain the aesthetic agency to shift and convert in to a multitude of objects by means of pattern, posture and movement.

LOIE FULLER: Research by Ola Maciejewska a performance report

The limits between the active agency of a performer and the agency of such a fabric are investigated in Ola Maciejewska’s project LOIE FULLER: Research. In a performance I was fortunate enough to witness in December 2017, Ola constantly re-defined a Dancing Dress using her performing body to give it new forms and representations. Two dresses, one black, the other a yellow-white one. Each one appears as a cloud of never-ending possibilities for representations. In describing the practice behind it, she writes that “It’s a physical practice stimulating the movement of matter receiving form, a movement that emerges as a result of the relationship between the human body and the object […] it focuses on facilitating forms that make that relationship visible. 3” What becomes visible only exists for a brief time, as a real-time metamorphosis is allowed to happen. The distinctions between performer and matter, form and movement start to erase. Ola’s practice is inspired by Loie Fuller, author of the Serpentine Dance, a choreographic piece which played with lightning effects and movement to create its spectacle. Fuller discovered that there was movement outside the body, this extension manifested itself in the Dancing Dress. To obliterate its true form even further, Ola makes use of the design to investigate its possible implications today. The motivation of the work is to shed light on to this in- betweenness, being between the body and the fabric and to overcome simple binary codes implemented in our way of perceiving. The distinctions between background/foreground, body/fabric, human/non-human casually blend with each other to create a more holistic relationship. The artist, being immersed in this piece of clothing, joins a new type of body which rejects conventional recognitions as something one. The real body here, is in something that the performer shares with the fabric, something that plunges in to our preconceived notions of a/b relationships and disrupts it. The pattern of binary thought breaks when we realize that a performer and an object have a more complex relationship. They might become the same, at least temporarily. Together they take on many shapes as the performance escalates and unfolds. The historic object (the dancing dress originally designed by Fuller) is recreated (more than a century later) and used as the generator of new meanings. This generates a longing to dwell in the in- between states of the mysterious relationship we can have with matter. Covering, in the way I perceive Ola’s work, not only refers to becoming other or enhancing an artist’s material relationship, but also has an agency in the way it pays a tribute to an existing art work. The Dancing Dress is not merely a small footnote in the work, but it is to continue the work. Appropriation is way to pay homage to, and seeing the possibilities that a work has today. A double rupture can happen when we trace the bigger history of a work like this. Ola presents a rupture for the now and the echos of a rupture that was created more than a century ago (when Fuller started performing with her Dancing Dress). The intention is to break the understanding of what it means to see things, and to experience them as constantly shifting in their identities and appearances. Of seeing them as they appear and disappear, making visible and blurring boundaries between objects and humans, assigning agencies to both of them.

Promotional image of Loïe Fuller: Research by Ola Maciejewska Photo credit: Martin Argyroglo.

Promotional image of Loïe Fuller: Research by Ola Maciejewska Photo credit: Martin Argyroglo.

My way

In music, a cover is a new performance of a previously released song by someone other than the original artist (Wikipedia definition). This means an artist appropriating an already existing song and delivering it with her own interpretation. This has to be done with utmost care and has layers of intentions; homages, tributes, alternative versions… What I see in the cover is a temporal rip in time, a way to seize something that exists and wrap it in the fabric of another type of music. But this fabric has some tear in it. Unlike the dancing fabric that helped describe the make-shifting dances and representational silhouettes caused by constant movements and patterns, this fabric is tubular. Tubular in the way we can see in to it, and through it. When artists weave this fabric of covering, there must be something they leave behind that references the original. Original here means the previous cover, or the song as performed by the previous artist. A cover is nothing without its revealing supplement. Revealing something about the past, or something about passions, interpretations. Any interpretation comes with layers of temporalities, voices, meanings, intentions, relevancies… Improvisation is possibly the only gate-way out of this binary between covering and revealing. Something of a freer sort, something that spins its own fabric, in real-time, in the making, in the moment.

Screenshot from a YouTube karaoke version of My Way by Frank Sinatra.

Screenshot from a YouTube karaoke version of My Way by Frank Sinatra.

Let’s look at what happens when a song is covered. Listening is learning through sound. Learning in the way you get to know someone, of repeatedly listening and gaining an understanding that way. I like to believe that an obsession with a song is behind every cover. And that obsession turns in to an active sharing made possible with the making of a cover. A song increases its territorial domain with each sharing, made possible by all the performing bodies. The performers make choices on the way as to how much of the original is left in there. Karaoke can be a way of covering. When somebody is on the stage performing Frank Sinatra’s My way, the performer embodies an image of Sinatra for that brief time. And in that time, the territory of a song increases, even if it disappears again when another song is performed. This temporal embodiment and voicing involves a reference to the real thing inside a staged event. Their distinctions lose their relevance. T h e My way contamination reaches new territories as it is brought out of the music industry and enters the karaoke bar via a performing body. To sing karaoke is to temporarily bring a spirit in to the space and increase a songs territory by means of simply sharing a passion.

One last example of covering I can give is one from myself. When I was younger, I used to enjoy pretending to be other people. People I looked up to, rock stars, actors… I’d try to get similar clothes, haircuts, attitudes from images or knowledge that I had of these people beforehand and just go for it. Stand in front of a mirror, imitating, going out, imitating. Not as to think that I was literally them, not up to the point where I was introducing myself as them, but more as a curiosity who I could become. To see how I’d feel experiencing myself as him/her. I would remain me, but I realized I could switch between identities. The image of the teenager holding a hairdryer in front of a mirror comes to mind. An embodiment that actively performs a duality but includes only one audience. The self splits in two, the image is in the mirror, the self becomes the one who gazes there and adores what he sees. This way, the adorer is the adored. A one-person show, one-person audience. Being immersed in the other, temporarily, is an act of covering. And there is a subliminal level of fandom. Whatever the circumstance (be it singing in front of a mirror with a hairdryer, singing Frank Sinatra in a karaoke bar), it offers a meeting of two realities. Becoming the other and seeing oneself as the other, simultaneously. The uncanniness brought about with seeing yourself and experiencing yourself seeing as an other brings about a radical self-referentiality in perceiving 4. In this sense, covering is felt in its utmost immediacy.

Being tucked away in a private space where this embodiment, in all its intimacy is possible. I ́m talking about covering as a breaker of boundaries between self and other. About it giving a multi-perspectival agency to the self, in a practical, artistic way. Try it out, an example would be re-interpreting Robert DeNiro’s famous performance from Taxi Driver… “You talkin’ to me?”

Bergur Thomas Anderson

Featured image: Gerard Ortín, installation view. Photo credit © Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona.

Foto: Pere Pratdesaba.

- http://www.mascontext.com/issues/22-surveillance-summer-14/abbott-h-thayers-vanishing-ducks-surveillance-art-and-camouflage/

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/a-painter-of-angels-became-the-father-of-camouflage-67218866/

- https://olamaciejewska.carbonmade.com/projects/5685373

- Brian Massumi, The thinking-feeling of what happens: A semblance of a conversation page 6