Vanishing Crowd: Una Björg and COVID-19

From the 16th of January till the 15th of March 2020 Una Björg Magnúsdóttir had an exhibition in the D-gallery of The Reykjavík Art Museum titled Vanishing Crowd. It was, at the time, an intriguing exhibition: integrating the whole space, it was simple and slow but complex, engaging and intimate. It was her first solo-exhibition in a museum, a big opportunity to exhibit in a big space and to work with our biggest museum – an institution that wants to give young artists opportunities. In this exhibition, which could be described as an installation, where the whole space was the work, Una played with our ideas of the event, of magic, of our belief in our common, societal habits; she played with our ideas of rationality, our tendency to venerate and revere, our ideas of expectation and action.

I am not talking about this exhibition today because there is nothing to talk about in art today – no, there is a lot to talk about in art today. I am talking about this exhibition today because the meaning and idea of this exhibition has changed completely in the months that have passed since it’s opening. Our whole art scene is in flux, art everywhere has been cancelled, postponed, made virtual, taken on a completely different form. As I write this our museums are closed, art venues are treading a fine line between wanting guests and keeping them away. The crowd has vanished. We do not know when it will come back. It might not come back, completely, for a long time.

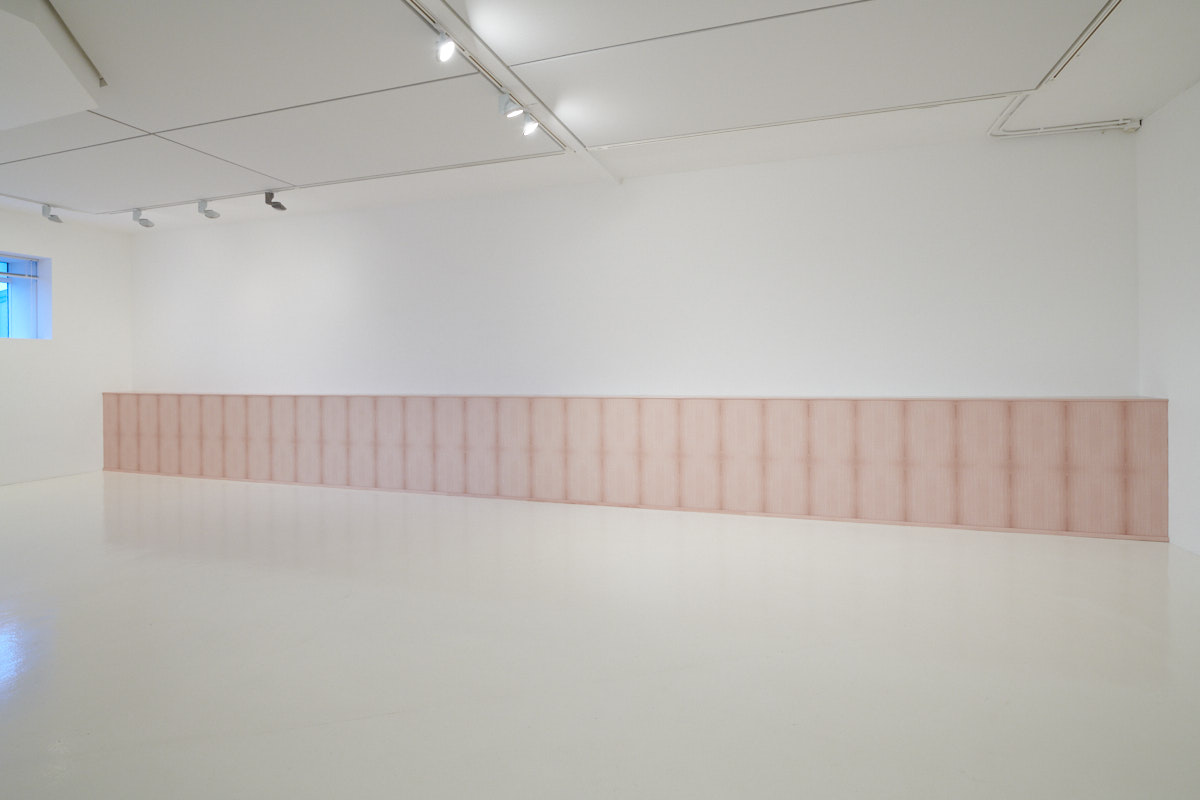

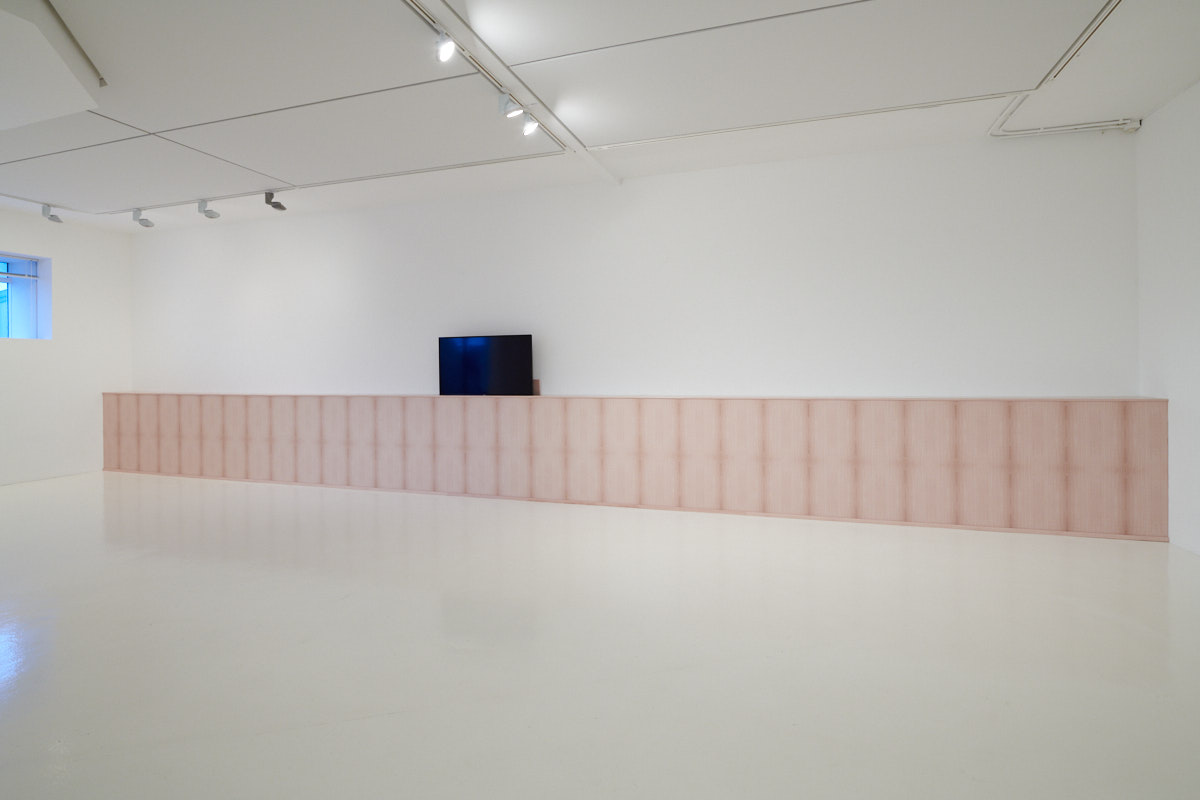

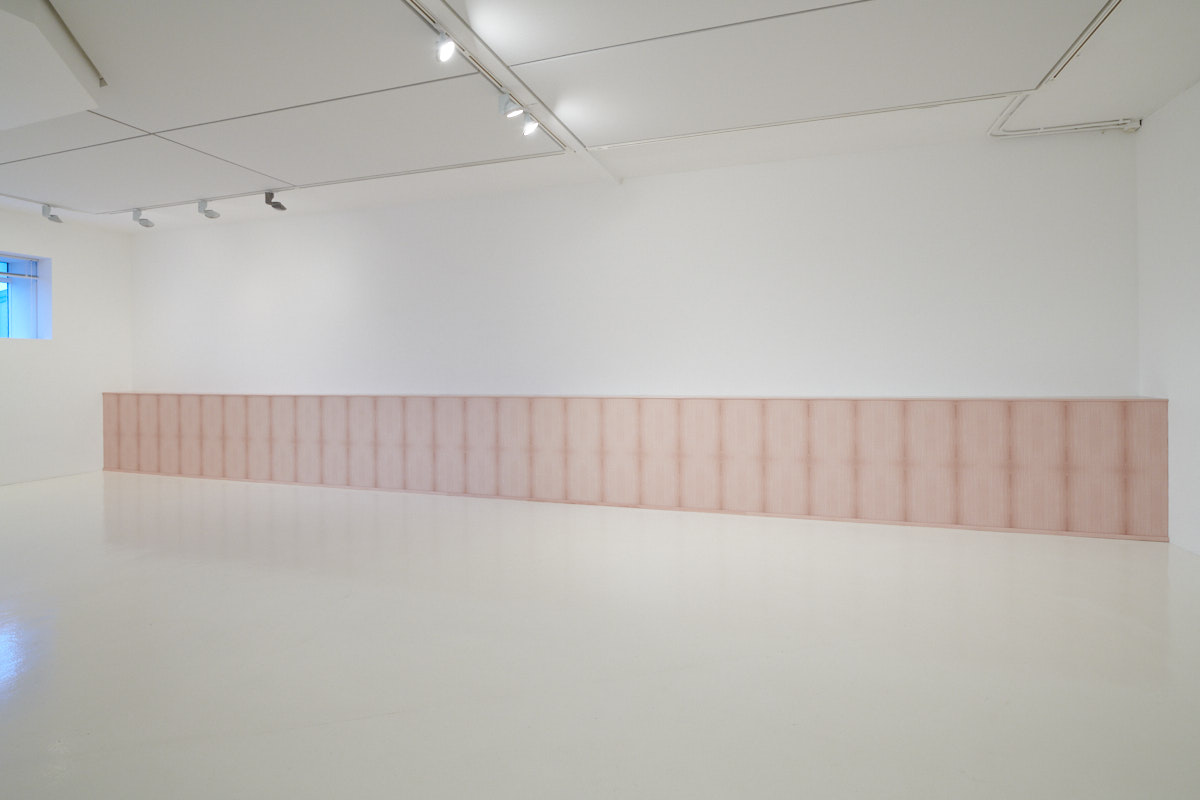

Vanishing Crowd, courtesy of the artist.

Vanishing Crowd, courtesy of the artist.

Una takes this title, Vanishing Crowd, from the magician David Copperfield. It is a trick he created where he makes a group of people vanish from a stage in a blast of smoke and noise and makes them reappear, almost instantly, somewhere else in the space where he is performing – to the audience’s shocked pleasure. In 2018, however, Copperfield had to explain, in detail, how he executed this trick when a volunteer sued the magician after being injured while taking part. The trick is sadly not as magical as Copperfield would like to have us believe. It mainly involves the people who vanish to go down a hole in the stage and to run, quickly, through a makeshift tunnel leading to the other side of the room. Magic does not have to be complicated, or necessarily a mystery, to work. This is where Una picks up the idea. The magic in her exhibition was partly in how she showed it to us, and then how she showed us how she showed it to us. If she asked us: is this magic? We would answer: no, this is not magic. If it is not magic then it must be reality.

If we are going to construct a convincing narrative for this year 2020, artists – if given the chance – could be the ones to do it. As has been said by others now as we come to terms with this in-and-out dance with the virus, art (maybe especially visual art) can be a tool to look at, interpret, see clearer what it is we are getting used to, what we are being asked to do, what has changed and what is changing.

Today we see the title of Una’s work in a completely different light, obviously, but everything about the work has changed. In a piece for the radio program Víðsjá Sunna Ástþórsdóttir said: Since suspense and excitement are highly infectious emotions, this exhibition is best experienced in a crowd. The crowd, and the different way people behave themselves in a crowd as opposed to alone, changed the way the work was magical, even artistic. Today the most magical thing about this exhibition is possibly that people were able to see it. The opening on the 16th of January was the last “normal” opening of the D-gallery before our present touch-free society took over. At the opening there were lots of people – close to each other, hugging, touching, together – it seems a long time ago. Our idea of the crowd has become complicated. The first COVID-19 infections in Iceland were confirmed on the 28th of February. The Minister of Health instituted a ban on public gatherings on the 16th of March, the day after Una’s exhibition closed. The crowd vanished, overnight. Not by magic but by a forceful intrusion of a very real event into our lives. This reality has changed Una’s exhibition. And it has changed every other exhibition since. And we should think about how it has done so.

Vanishing Crowd, courtesy of the artist.

Vanishing Crowd, courtesy of the artist.

We could say a ghost has gotten into Una’s work, has taken possession of it. It is unnerving, the exhibition has become a bit frightening, and it has maybe become less understandable, but extremely relevant. Now vanishing means vanishing, we know what that looks like. Vanishing from the streets, from the museums, the pools – to no longer see or be seen in the shared arena of our society. Vanishing means to stay home, to be forced back home, to be sick. For too many people it means to grieve, to pass away. Last winter vanishing meant to go away but it still also meant to come back. We expected to come back, that it would be possible to come back, like the screen in Una’s work that appeared and disappeared on a regular schedule. Today it looks like this timeframe could be longer, the coming back more complicated. It might become a regular thing to open up and close again according to how the virus spreads each time. This is not only forcing postponements and cancellations of events that were supposed to take place over the summer or this autumn, but now having an effect on how and what we organize in the coming year, and even beyond. An indefinite timeframe will only continue to complicate our work. How can we make this situation clearer, more accessible, less claustrophobic?

Because the question now is not if we can come back to normal but rather what will be the new normal we come back to? Should we expect a crowd or not? How important were openings to us? What is an extended opening? Hopefully this will be a normal where there is a vaccine and a definitive answer to this threat has been found. Not a normal of apathy, tiredness, and an aggressive politicization of this situation. And even though we might sense that there has been a rupture between then and now, between pre-virus and post-virus, we cannot look at this event in a vacuum. This virus happened to a society with a certain structure and a certain context and the response to it exists within that same context.

We are seeing, in real-time, a reevaluation of how we perceive the value art has in our society. For the first time, it seems, a sitting Minister of Culture has a clear idea of the challenges an artist faces in their day-to-day work, and how the cultural infrastructure in Iceland is not at all prepared to deal with an emergency, of this sort or indeed any other. We are seeing a conversation start to develop around how we should value museums, galleries, art institutions, when that value cannot be counted in attendance figures and ticket sales. That is not to say that ticket sales were ever a reliable indicator of, say, the success of a museum in Iceland, but there is a clear difference between 1,000 guests (with the goal of attracting more) and none. Maybe especially so in the eyes of a government official attempting to leverage artistic production as, say, a tourist attraction. This is a necessary conversation that we need to engage with.

The first lockdown in the early spring did not last long enough for us to be forced to think deeply about what effect this would have on art in Iceland. We were able to open back up relatively quickly, and we quickly tried to get things back to normal. Now, however, we see that this could very well take a long time, and that art as we knew it will not come back overnight, but most likely gradually and in steps. And if we take that position we must take time now to develop these conversations. What does art look like without the usual relationship between artwork and exhibition guest? Can moving art into the virtual realm ever do more than to remind us how much, in our constantly distracted online existence, we now miss actually physically interacting with objects, spaces, people? If COVID-19 has forced us to look at our world and think about what we really think is important then we might also be able to ask ourselves how brave and how new we can remake our world? Or are we looking for it to be the same as it was? In any case, the money that the government is now putting into the culture sector should spur us to take on this conversation and to bring it to a wider audience.

Vanishing Crowd, courtesy of the artist.

Vanishing Crowd, courtesy of the artist.

It is not possible to fully express how Una’s exhibition has changed or will change, or will mean in the end. We might not even know really what the magic there is or was, or what or where the art was exactly. Because we are still too deep inside this event. Where the pillars of this society we have built are trembling, possibly shaking. Where nearly all of the day-jobs that artists have relied upon for the past decade have disappeared. Where meeting friends and family, or going to the studio, has become a threat and a calculation of odds and safety precautions.

We know that this virus has already changed art because it has changed the world. It is important to think about what has changed. It might not be obvious. This virus enters into us now and we will come to see our history from a different body. Hopefully we will see the stage at some point from the other side of the room – appearing again in the crowd as if by magic. But we are still running somewhere through the tunnel. The masked audience is looking through the smoke to the stage and still do not see anyone.

Starkaður Sigurðarson