What’s more monumental than buildings? a show and tell with Melanie Ubaldo

Until we take the time to know any place intimately, our awareness is often limited to our associations with their landmarks and stereotypes. When I visit new places, I pay extra attention as I trace the land with my feet to orient myself until foreign feels familiar. The more I walk, the more I know. I gain my bearings in life through walking, and trusting that my feet will eventually reveal to me something I did not previously know. Paths I walk again and again are imprinted in my memory with each footstep – familiar textures, ways of moving, views and rituals that are, over time, carefully imbedded into the soles of my shoes. I walk to understand, to see more (or all) sides and angles, and to instill considered consciousness.

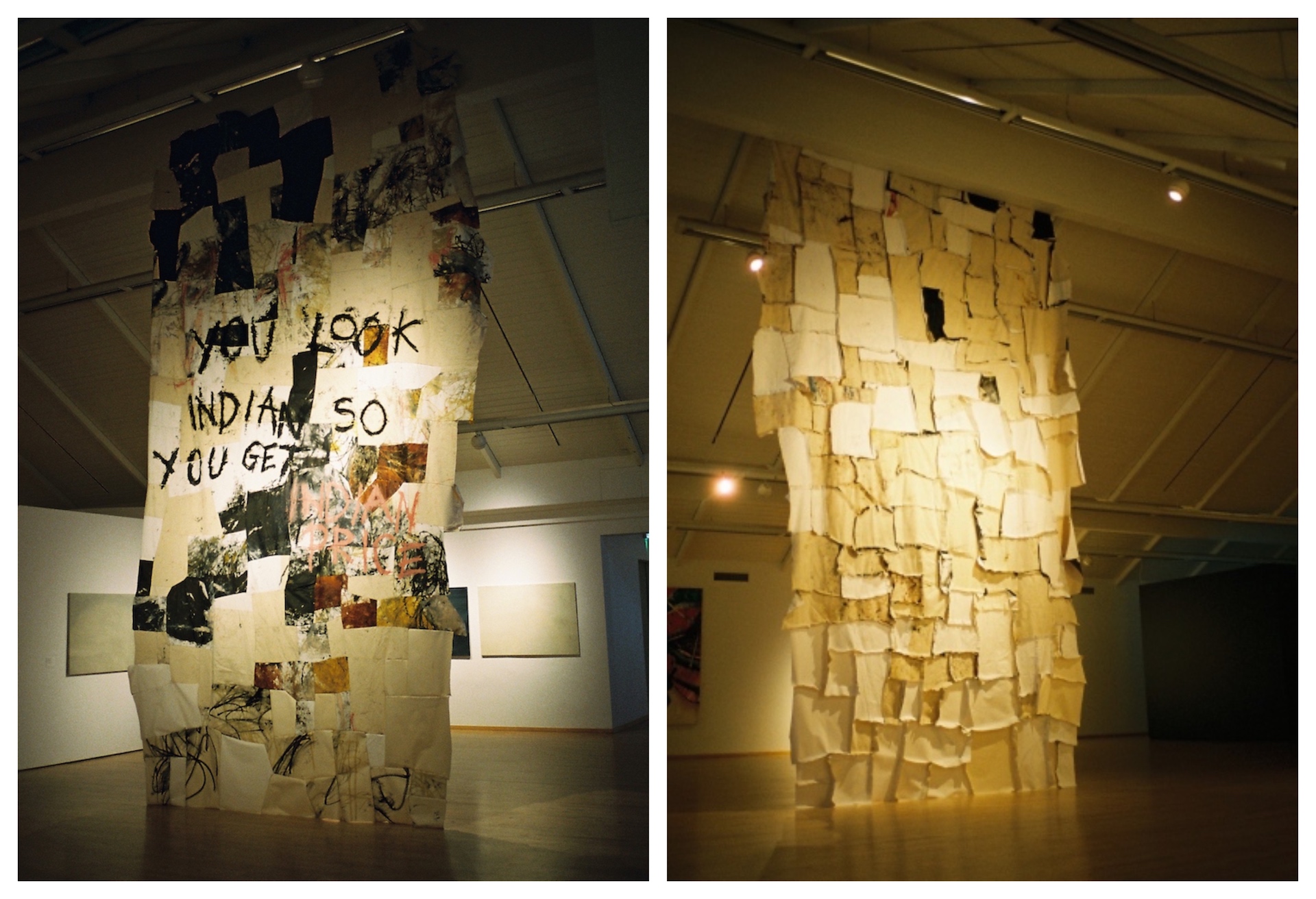

Reykjavík-based artist Melanie Ubaldo makes work that activates my whole body. I need to walk around it, move closer, step back, smell the thick brushstrokes of paint, and visually take in all the textures and materials, often wishing that I could experience these puzzle-like paintings through the touch of my fingertips. I’m constantly aware of their scale, towering over me, unable to be ignored. Personal phrases are so boldly written across the raw, unstretched, paint-splattered, patched and sewn canvases, which catch my eye immediately. Her work celebrates her Icelandic-Filipina identity while also confronting the challenges of intersectionality. The core of her work is rooted in her relationship with her mother, with some phrases even coming directly from their past conversations. A chaotic mix of vulnerability and (dis)comfort, Ubaldo’s work acts like a billboard or banner documenting her lived experiences.

Throughout my recent conversation with Melanie, she spoke fondly about her curiosity with architecture, and what makes something (or someone) monumental. Her paintings and their phrases dominate any given space they are placed within, ensuring that we hear her messages loud and clear. There is an undeniable reference to architecture with her paintings as they mimic posts, pillars, buildings and obelisks, along with an unwavering awareness of space, as they tend to be supported by the architecture themselves.

You look Indian so you get Indian price, 2017

You look Indian so you get Indian price, 2017

Part of the exhibition Málverk – ekki miðill / Painting – Not a Medium at Hafnarborg, Curated by Jóhannes Dagsson.

While it’s easy to correlate scale with dominance and aggression, the core of her work and her person simultaneously brings forward a delicate quality. As much as these paintings draw inspiration from the grandiose of buildings and billboards, I consider them just as much a reference to shelters: tarps, coverings or perhaps even a slight nod to a child’s comfort blanket. There are clear parallels between Melanie’s paintings and Korean artist Do Ho Suh’s sculptures and installations as they both touch on notions of space, home, memory and (dis)placement. Suh’s intimate sculptures replicate and reference various places he’s lived and worked (as well as many of the objects within them) out of delicate steel frames and sheer gauze-like fabrics, almost mimicking tents as they exude a sense of portability. Their material lightness gives them a transitory quality, while being so conceptually present that they concurrently call to be contemplated. Melanie’s work, much like Do Ho Suh’s can only benefit with more time and care spent in their vicinity as the layers slowly unravel to let you in.

I also can’t help but be reminded of the strong women who led the Feminist Art movement as I reflect more on Melanie’s practice. The Guerilla Girls’ The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist (1988), for example, directly confronts the countless injustices and prejudice that women continue to experience in the arts. There also exists some striking similarities in Tracey Emin’s mark making and Melanie’s that firmly places their work in close dialogue with one other. Many phrases and sentiments in these works continue to ring true over 30 years later, and I wonder (and fear) if the words and sentiments in Ubaldo’s paintings will also remain true in decades to come. The works of all these women are vulnerably bold, courageous and unapologetically blunt, laced with an honesty that quivers between comic and devastating. The longer I spend with Melanie’s work, the more I realise how genuine it is, and I never know if I should laugh or cry.

What are you doing in Iceland with your face?, 2017

What are you doing in Iceland with your face?, 2017

Initially exhibited in Slæmur Félagskapur in Kling & Bang in 2017 and most recently shown in the Borgarbókasafn in Tryggvagata as part of the project Inclusive Public Spaces.

Alongside her individual painting practice, Melanie works in a collective with Darren Mark and Dýrfinna Benita Basalan. Brought together through their shared memories and experiences of all being Icelandic artists with Filipino origins, their collaborative work as Lucky 3 is rooted in nostalgia and diaspora shown through their common culture(s). Their recent exhibition, Lucky Me? at Kling & Bang affectionately gathered key elements of Filipino life and culture – from karaoke, to playing basketball in the streets, to a colourful sari-sari store[1]. Speaking of this exhibition led us to speaking about her family, and the struggles she’s had with often feeling like she’s disappointing her mother by pursuing her art practice. Melanie divulged that she felt as though this recent project with Lucky 3 was perhaps the first exhibition that her mother was proud of, but that the pride likely stemmed more from seeing that Melanie (and in turn, her Filipino culture) was accepted by the community and her peers rather than pride in the work itself, or of her daughter.

One day while Melanie was sitting the show, she told me that a guest (an older white male artist who was visiting Iceland) felt the need to mention that he had already made an identical or similar work to theirs, but decades earlier. His comments were specifically targeted towards a sculpture that referenced a broken glass concrete block wall. These types of concrete walls with shards of glass scattered atop of them are common in the Philippines as a means of property security and to deter trespassing. Perhaps his comments were meant simply as gallery small-talk, but they came across to her more so as a microagression that unnecessarily asserted inherent power dynamics. Melanie also mentioned that some local guests visited the show as a means of “research” as they were planning to visit the Philippines in the near future. These instances only further instill the fact that the identity and heritage of visible minorities is still overall irreverent or exoticized in the arts, rather than respected as a means of auto-biographical storytelling, self-expression or sociocultural critique.

The Wall, 2019

The Wall, 2019

Installation shot from Lucky 3 presents Lucky Me? at Kling & Bang.

Sari-Sari Store, 2019

Sari-Sari Store, 2019

Installation shot from Lucky 3 presents Lucky Me? at Kling & Bang.

In Roxane Gay’s essay, When Less is More, she poignantly states that “this is the famine for which we must imagine feast[2],” as she unpacks the many racial tropes in Orange is the New Black in spite of it being globally praised for its diverse cast. Gay is essentially saying that there remains so little diversity in pop culture, that the presence of minorities is praised even if they’re present as a means of feeding into cultural stereotypes. Roxane Gay’s statement is in line with of how Audre Lorde eloquently explains that it is not our differences that divides us, but that it’s rather our inability to recognize, accept and celebrate our collective differences[3] that in turn leaves us divided. This reality still exists in most (if not all) aspects of our world to this day, and the arts is far from neutral in regards to this. I couldn’t help but notice that an overwhelming majority of the shows and projects that Melanie has been curated into were about race, sometimes under the guise of “inclusivity”. I find this problematic as it then suggests that work aside from hers (or other work like hers) is “exclusive,” meaning that her voice is in turn excluded from those other dialogues. It’s deeply personal work, and while Melanie willingly confronts the conversation of race through her work, to place her practice solely under the umbrella of being about race feeds into a deeply systemic problem in and of itself. Her work is autobiographical, so it naturally draws connections to her identity and heritage, but there are so many other streams and subtleties that her practice flows in and out that are seldom acknowledged. When I contemplate Melanie’s work, I see the angst of parent-child dynamics, strong references to architecture and building, relatable and satisfyingly self-deprecating humour, commentaries on our collective (mis)use of language, a visceral relationship to her materials and tactility, and nods to various art movements – all through the complex lens of her personal lived experiences, heritage and culture. Frieze London’s Artistic Director Eva Langret, in a recent interview with Aindrea Emelife, explains that to mostly (or only) work with BIPOC[4] artists within the context of race and identity results in a lack of nuance when it comes to integrating their voices within wider artistic discourses[5]. What may often be done with genuine interest and good intentions can further be read as an uncomfortable mix of voyeurism, othering and performative solidarity. Art can foster diversity and practice proper inclusion if we let it, so to continue this pattern deeply dilutes the power of art, making it to fall stagnant and complicit to the dangerous narrative that marginalized artists can not take up the same or as much space without the additional emotional labour of tokenism.

At the time of our conversation, Melanie mentioned that she was immersed in various fiction novels as a means to escape and rest her mind. She said that she’s taken by how they’re written, and they act as her way to pause on the weight of reality. That statement hit me immediately, as it made it all the more clear how real and raw her practice is. She can’t escape reality through her work, as she’s given no space for the division of who she is and what she does the way that many other artists (perhaps unknowingly) have the privilege of doing, but she rather needs to confront her world head on. To know Melanie’s work wholeheartedly is to spend time with it, letting the words really sink in, acknowledging their scale, and walking around them in order to see and know more. As the intensity, aesthetics and boldness of her work alone can be seen as monumental, the energy and courage that fuels it undoubtedly takes precedence.

Juliane Foronda

[1] A sari-sari store is a neighbourhood convenience or variety store in the Philippines.

[2] Roxane Gay, When Less is More in Bad Feminist: Essays, 2014., p.253.

[3] Audre Lorde in Berlin, Audre Lorde – The Berlin Years 1984-1992, 2012.

[4] BIPOC stands for Black, Indigenous, and People/Person of Colour

[5] Aindrea Emelife, ‘“There Is a Lot of Hard Work to Be Done”: How the Art World Can Step up for Black Lives Matter | The Independent’, 2020.

Melanie Ubaldo (b. 1992, Philippines) is an Icelandic artist based in Reykjavik. In Melanie’s work, image and text are inextricably linked, where deconstructionist paintings incorporate text with graffiti like vandalism, oftentimes of her own crude experiences of others preconceptions, thus exposing the power of immediate unreflected judgment. She received her BA in Fine Arts from Listaháskóli Íslands in 2016.

Cover picture: Thanks Mom, 2016. This work’s phrase is from a conversation that Melanie had with her mother about going to art school. This was her BA graduation piece from LHÍ.