First floor to the left / 1.h.v.

First floor to the left / 1.h.v.

At Langahlið 19 in east Reykjavík is the home gallery of Guðrún Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir, named after its placement in the building, 1.h.v. (Fyrsta hæð til vinstri), or first floor to the left. The first exhibition was in 2012. Guðrún lives in Finland and in Reykjavík during the summers, where she holds exhibitions in her flat. Before moving to Finland, Gúðrun was involved in The Living Art Museum (Nýlistasafnið) and participated in curatorial projects. 2016 is the fifth summer and the sixth exhibition at the flat. I visited 1.h.v. to have a guided tour and interviewed Guðrún about the space.

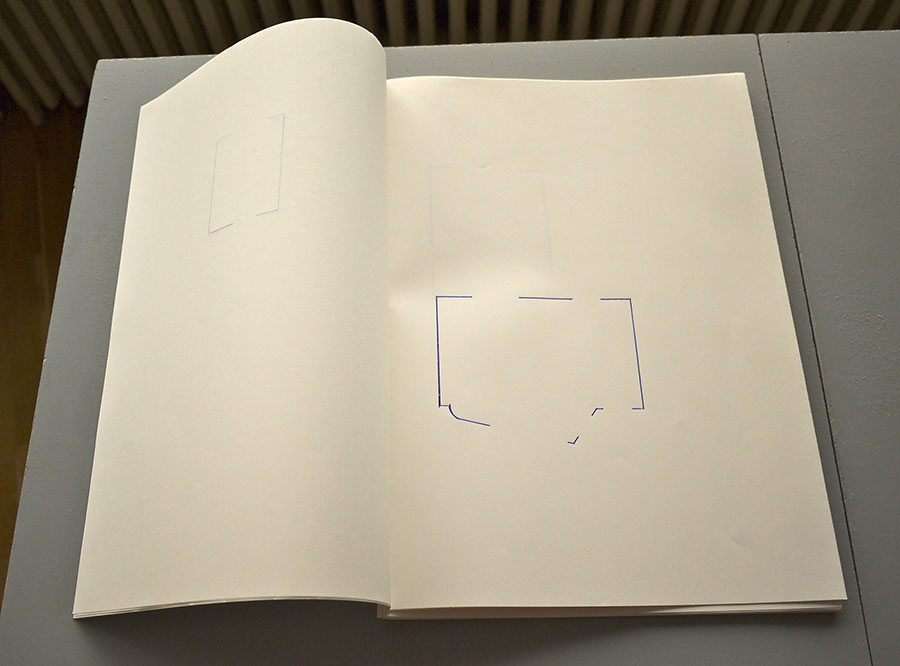

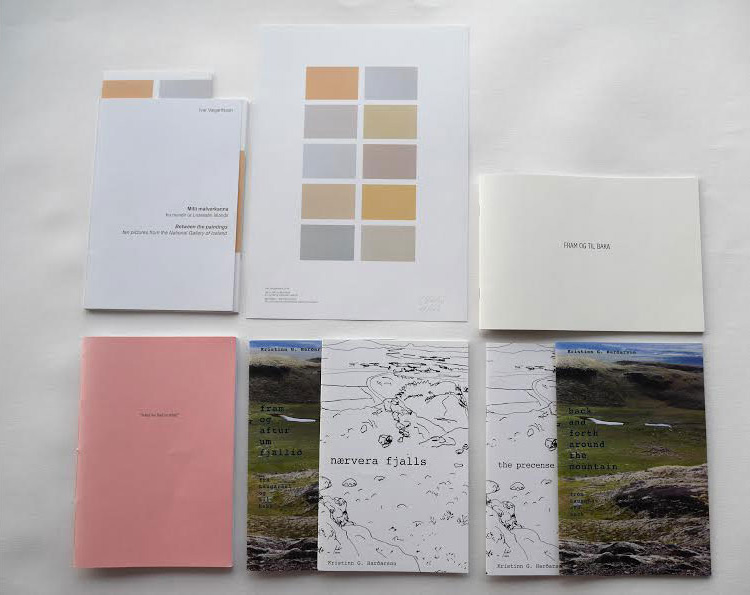

The first exhibition in 2012, of works by Sólveig Aðalsteinsdóttir, began as a bookwork project. In fact, the plan was to publish bookworks along with every exhibition. Bookwork by Sólveig from this exhibition consists of layers of six pages of tracing paper; the artist has drawn on the top page so the rest of the pages show softer and softer markings. The drawings represent the space of the apartment, which consists of six rooms. Sólveig created a drawing, a large outline of the architecural layout of the apartment, and an edition of ten sets of six handmade books. From a text accompanying the exhibition: “The subject of both the drawing and the book is the architectural layout of the apartment; explored through line, form, layout and the duplication. In the production of the book ordinary printing techniques are avoided as simple handmade methods are preferred.”

Guðrún chooses artists who she thinks can make a dialogue with the space and between the two artists who are invited to exhibit together in the flat. The first exhibition was with Sólveig, but then the project just kept evolving. She prefers the project to stay open-ended. The second exhibition was held in 2012 by Ingólfur Arnarsson, and Ingólfur’s work above the windows in each room has remained in the flat. It is a color palette on the ceiling reflecting the hues of the colors outside the windows. Ceiling Painting in front of a window in four rooms. Household paint on white ceiling. The chosen colors meet the visitor inside the apartment based on colors outside the window.

The exhibition held during the summer of 2013 was of work by Carl Boutard and Eggert Pétursson, artists who had never previously worked together. Carl, from Sweden, started with an illuminated vitrine containing objects in pairs. Eggert showed small floral paintings and photos showing the inside of the paintings. Later they decided that everything in the apartment should exist as a pair: two tables, two chairs, two dressers, two flowers, two vases etc. The bookwork was a reworking of Eggert’s book from 1980, „what I had in mind“. The new version was called „what we had in mind“. Eggert explains the bookproject:

Early in the year 1980 I sat at the desk of my studio of the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht, Holland, with a pile of paper. I closed my eyes and waited for images to appear in my mind. The moment something appeared I quickly sketched an image and soon a substantial pile of drawings had accumulated: pictures of houses, landscape and so on. Faces were excluded. In the following weeks I cycled around Maastricht and the surrounding area with a camera in hand. Whenever I noticed something in the environment that resonated with my drawings I took a picture. This resulted in nine drawings and nine photographs, which were later printed in a small booklet called “what I had in mind.” Two years ago Guðrún Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir showed Carl Boutard the book. When she invited Carl and myself to exhibit at her home gallery, 1 h.v., Carl came up with the idea to repeat this process which I agreed on. Early this year I sat down with a pile of paper in my apartment in Stavanger, Norway, and drew sketches in the same manner as I had done thirty-three years ago. I sent the pile to Carl, who immediately started to search for subject to photograph inspired by my drawings. What I had in mind became what we had communally in mind. Countless participants can now repeat the piece in multiple different ways.

Having a gallery in your home could bring many variable outcomes, however, it seems that the conceptual art exhibited here is often unobtrusive and minimal. “The quality of being in a home,” Guðrún says, “is that it automatically ties things into the everyday. I think also when you exhibit in a home you see new possibilities because it’s very different than a gallery space. It changes very much how the visitor approaches the gallery. They start to talk more perhaps. I think the artists definitely take into account that they are exhibiting in a home. I hope the two artists exhibiting can create some kind of dialogue, but it comes about naturally based on who exhibits together.”

The following summer of 2014 Magnus Pálsson exhibited drawings from different times. They were ideas and sketches for works.

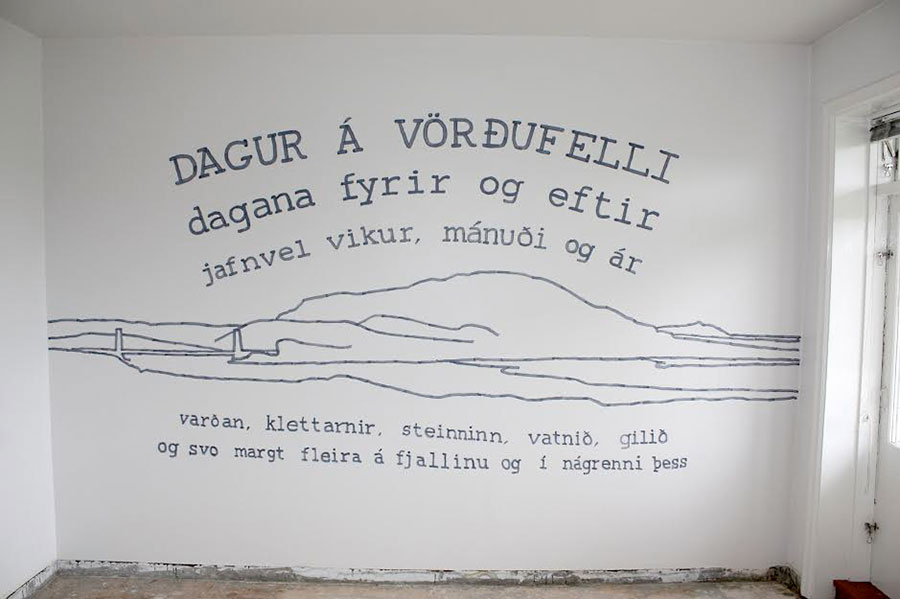

Kristinn Guðbrandur Harðarson did an installation around Mount Vörðufell. Excerpt from a text about his contribution:

Kristinn’s works in the exhibition form a type of portrait of Vörðufell in Biskupstungur. Kristinn has had a number of close connections to the mountain and its surroundings for years. The artworks are diverse in style and form. A travel-story in the form of a book narrates the story of climbing the mountain last autumn. A second book is a reflection on the artist’s closeness to the mountain and knowledge about it gathered throughout the years. Simultaneously the book contains biographical fragments, although those are set within a frame limited by time and location.

Another work consists of text attached to a doorframe. The text presents fragments from walks on and around the mountain over the past decades. There are also two photo collages, firstly focusing on Úlfsgil gully on the southern slopes of the mountain and secondly focusing on the nearby area of Birnustaðir farm. Finally a mural poses as a kind of title page for all the works in the exhibition. During the past few years Kristinn has created works based on his excursions and research of his local area. The works in this exhibition as well as many of his previous works are inspired by oral history, travel stories and the exploration of Icelandic nature by landscape painters such as Kjarval, Ásgrímur and others of their generation.

The summer of 2015 was more of a private exhibition showing many artists: Guðrún Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir, Ragnar Jónasson, Sólveig Einarsdóttir, and Guðrún’s brother Jónas Ragnarsson. The exhibition included mainly drawings and photos created by Jónas when he was a young man. Jónas’ son Ragnar made an installation of his father’s drawings of boats sailing at sea, which were hung on one wall and on the opposite wall Jónas’ sea landscape slides were projected. The other exhibiting artists, Guðrún Hrönn Ragnarsdóttir and Sólveig Einarsdóttir, also referred to Jónas’ work in their own work.

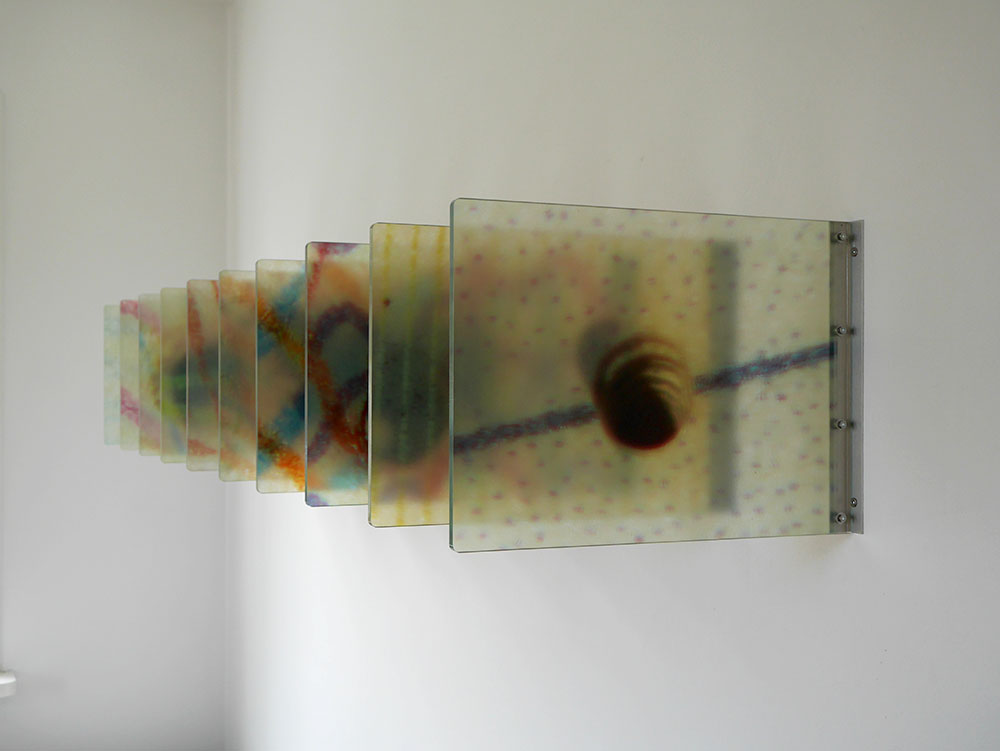

Now on view at 1 h.v. are works by Inga Þorey Jóhannesdóttir and Ivar Valgerðsson. Inga Þorey presents Fram og til baka, a walk through passports representing the borders between Syria and Iceland. A very organic texture, like tattooed skin, is photographed and set on clouded glass. Each passport has its own aesthetic of pattern and emulsion where the enlarged punchholes create a tunnel linking them together. Each page in every passport has the passports number punched or laser burned. (these holes can be seen on the bottom of each page in every single passport). The ten countries include Syria, Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, Hungary, Austria, Germany, Finland, and Iceland.

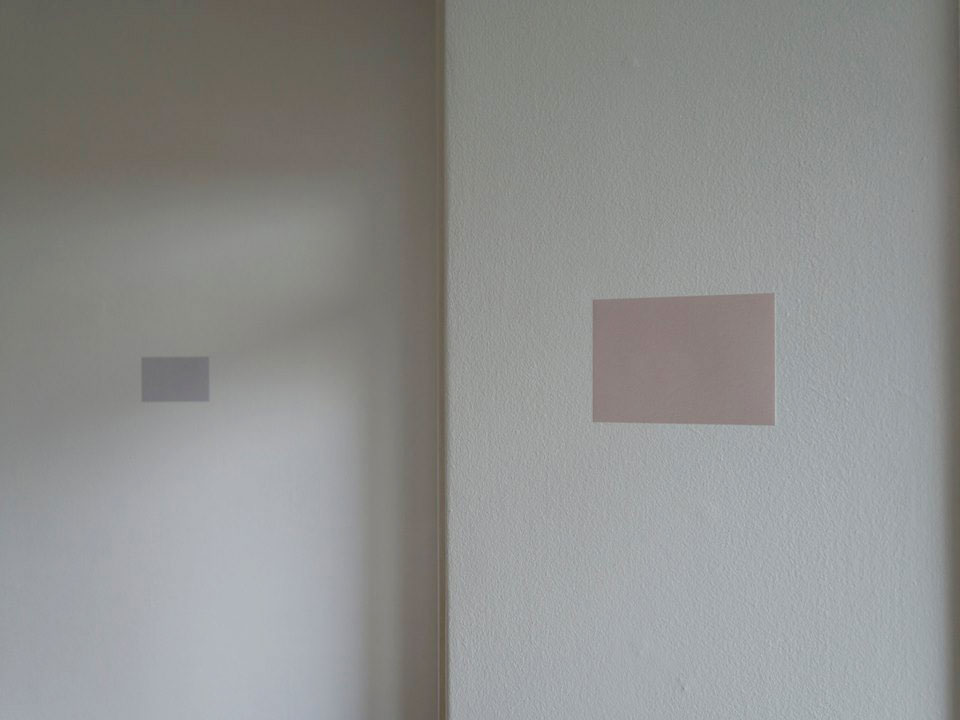

Ivar’s work Between the Paintings: ten pictures from the National Gallery of Iceland is an installation placement of what appears as paint sample cards on the walls. These are photographs taken of the empty white walls in between the paintings in an exhibition held at the National Gallery of Iceland. They display the camera’s diverse interpretation of color nuances, light, and surface in the museum halls based on their placement. Ivar created a bookwork in connection with the installation.

Iceland has a history of innovative exhibition spaces. There was Gallery GÚLP! in the mid-90´s which held exhibitions in a shoebox-sized box. There is Gallery Gangur (The Corridor), another small home exhibition space. There is also Gallery Gestur in a small briefcase, which creates the atmosphere of an exhibition opening in whatever space it is opened. There is also a gallery in a rusty shed, The Shed, which migrates around different inconspicuous locations around Reykjavík.

Guðrún has created an innovative space for conceptual and minimal art that is not separate from where she spends her daily life. The production of bookwork from each exhibition adds to the architectural study of the space, as some aspect of the 3-dimensional transforms into 2-dimensions.

Erin Honeycutt

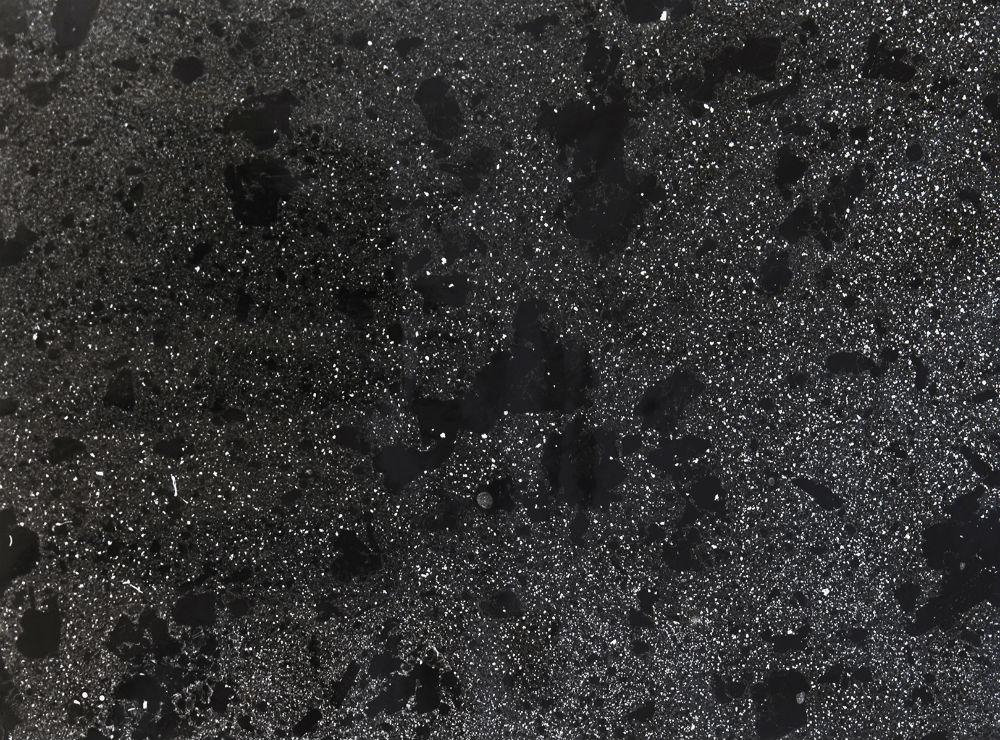

Detail of Hraun (2016)

Detail of Hraun (2016) Hraun (2016) No. 6281 and 6285, Gelatin silver print, 100 x 150 cm, Rock type: Gabbro xenoliths from silicic tuff, Place: Kambsfjall, Króksfjördur, Vestfirdir, Iceland, Age: 10 million years old, Petrographic slides borrowed from the Icelandic Institute of Natural History

Hraun (2016) No. 6281 and 6285, Gelatin silver print, 100 x 150 cm, Rock type: Gabbro xenoliths from silicic tuff, Place: Kambsfjall, Króksfjördur, Vestfirdir, Iceland, Age: 10 million years old, Petrographic slides borrowed from the Icelandic Institute of Natural History Holuhraun lava field

Holuhraun lava field Geologist Morten Riishuus and microbiologist Anu Hynninen at work

Geologist Morten Riishuus and microbiologist Anu Hynninen at work Geologic tool

Geologic tool Víti Crater

Víti Crater Lava from Holuhraun eruption

Lava from Holuhraun eruption

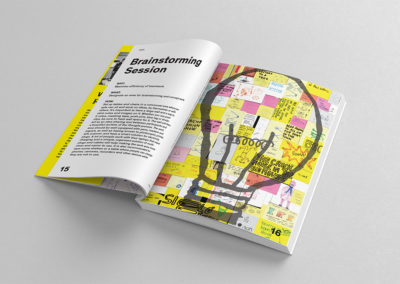

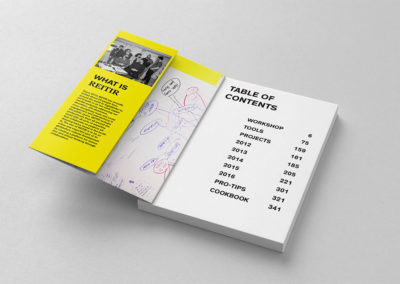

For the past months they have immersed themselves and a few other trusted collaborators in a comprehensive and detailed examination of the elements and structure of REITIR. The outcome is a book that is set to be published later this year.

For the past months they have immersed themselves and a few other trusted collaborators in a comprehensive and detailed examination of the elements and structure of REITIR. The outcome is a book that is set to be published later this year.

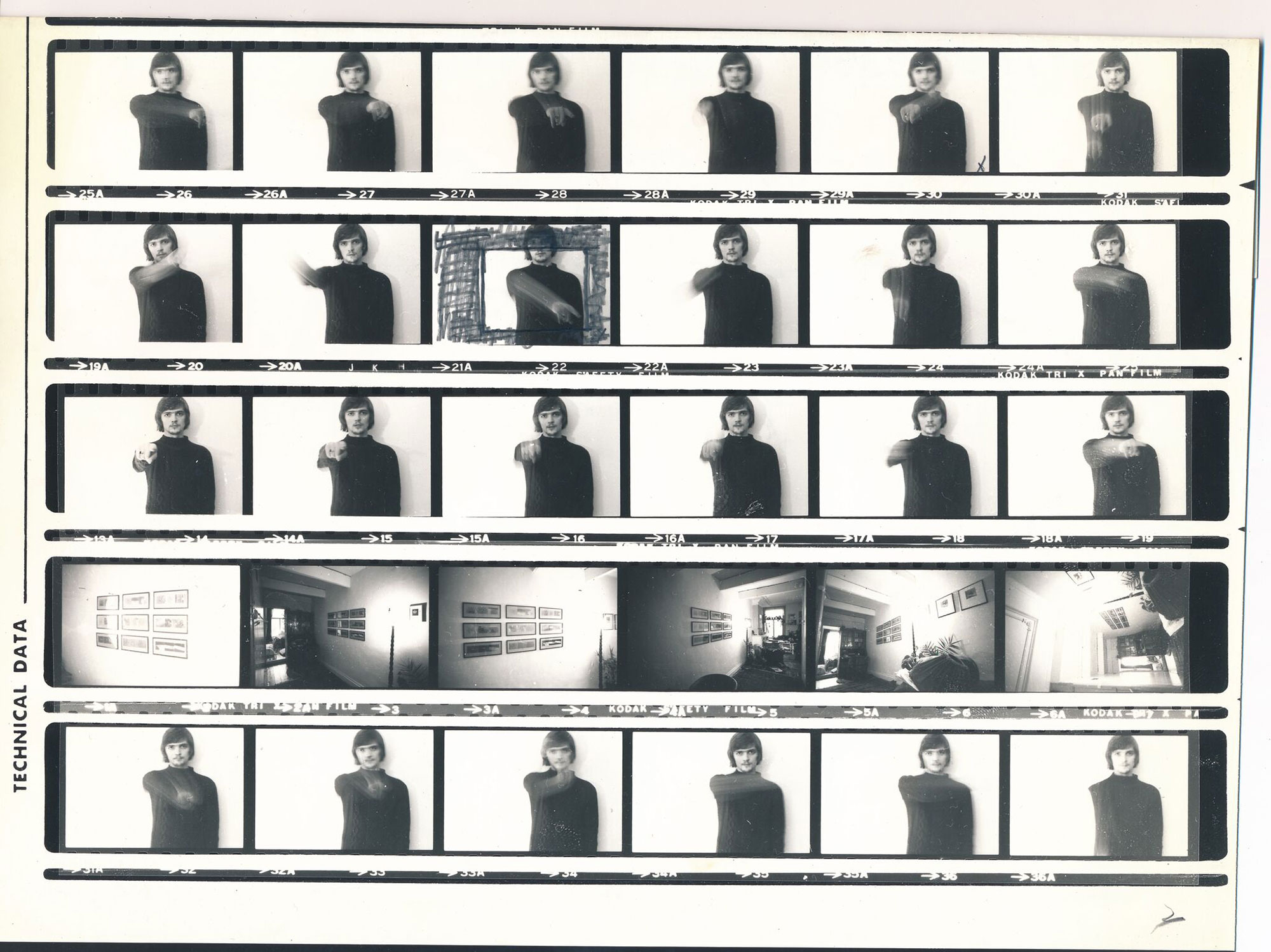

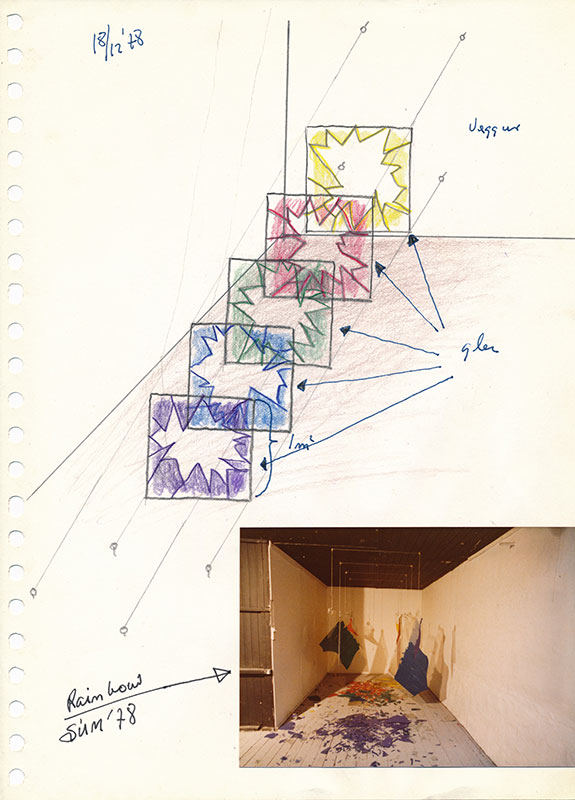

Curators Þorgerður Ólafsdóttir, Director of the Living Art Museum and Collection Manager Becky Forsythe have titled the exhibition Rolling Line, the namesake to a photographic work Ólafur completed in 1975. The artist himself is seen somersaulting through nature within Rolling Line, and the work references the possibility of a continuous line always ending in a circle. This reflection is well related to the core of the exhibition, which aims to shed new light on the process and period of the artist, from 1971 when he started as a student in The Icelandic College of Art and Craft, until the early eighties when Ólafur began to turn away from one of his main mediums, the photograph.

Curators Þorgerður Ólafsdóttir, Director of the Living Art Museum and Collection Manager Becky Forsythe have titled the exhibition Rolling Line, the namesake to a photographic work Ólafur completed in 1975. The artist himself is seen somersaulting through nature within Rolling Line, and the work references the possibility of a continuous line always ending in a circle. This reflection is well related to the core of the exhibition, which aims to shed new light on the process and period of the artist, from 1971 when he started as a student in The Icelandic College of Art and Craft, until the early eighties when Ólafur began to turn away from one of his main mediums, the photograph. Rolling Line, 1975

Rolling Line, 1975