Post-Digital World(s) of Icelandic Art

Post-Digital World(s) of Icelandic Art

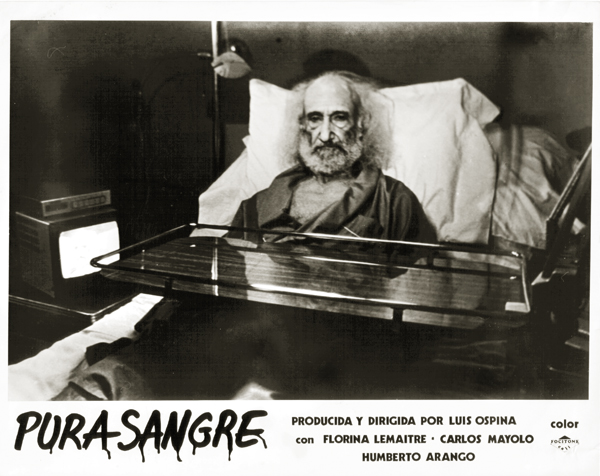

Writing about contemporary digital culture in mid-2020 has a different context than it did at the beginning of the year. In the midst of a global pandemic in which the Merry-Go-Round of the art world has been brought to a standstill brings a new consideration of the digital world as it has suddenly become the safest, available, and dynamic tool for continuing with life amongst new social distancing measures and limited travel possibilities. Like most sectors of daily life, the art world has been pushed to go digital. With the closure and alteration of how we experience some artworks in museums and galleries because of control measures, digital artists have been able to carry on as usual. Galleries and museums have offered virtual renderings and video walk-throughs of exhibitions, resurfaced 3-D tours, and more video content from the archives. One meme from the anonymous Instagram account @JerryGogosian captured the nuances of inhabiting a viewer’s perspective in the worlds of an online platform of contemporary art with a few chosen grammar decisions. (See featured image)

There is no doubt that the pandemic will influence the kind of art made during this time and in the years to come – especially in using the ever-present digital medium that has become even more a tool for carrying messages and presenting art on a digital platform. Digital artists already enmeshed in the medium are then at a certain forefront of these times ahead. Within Icelandic art history, the introduction of the digital came relatively later than other mainland art scenes. However, this has led to a particular relationship between the digital and more traditional art forms, especially traditions that are rooted in Icelandic culture, such as the landscape painting, which offers a tactile sense of the way people connect to landscapes both under the feet and in the mind.

A new publication titled Digital Dynamics in Nordic Contemporary Art focuses on the manner in which contemporary art is changing in the era of the digital. Margrét Elísabet Ólafsdóttir, author of one of the book’s chapters, “Divisions and Divides in Icelandic Contemporary Art,” offers a timeline of the digital and new media arts in Iceland – one can see how global art movements diffused in Iceland tend to take on a characteristic of being intensified and clearly traceable, just as smaller models are easier to trace. In Iceland, there are certain instances, for example, when in the 1960’s the discrepancy between Iceland and the US in terms of access to technological equipment was vastly different – the militarized US was leading research in the field, while Iceland had limited access. This discrepancy in hindsight can be seen to have allowed the Icelandic art scene to develop in unique pathways that did not so readily grasp onto the digital, but considered it from a distance for a few more decades, cultivating a sensibility towards the divisions and divides between the digital and more ‘traditional’ mediums and create an aesthetic bridge between them. In a panel discussion in conjunction with the book launch, artist Auður Lóa Guðnadóttir, for example, describes the way in which she brings the imagery from the digital into a physical space by making 3d objects of subjects and motifs of digital culture such as funny animals, cucumbers, and fruit emojis as a way to work within the barrier between those two worlds.

When in the mid-1980s, video became part of the curriculum at the Icelandic College of Arts and Crafts in the New Media department, there was one camera and no postproduction studio. Steina Vasulka’s exhibition in 1983 was shown in Iceland on limited monitors because of a lack of equipment. Compared with the rest of the contemporary art scene around the Western world, it allowed more time to reflect on actual and virtual worlds. In 1999, when Iceland Academy of the Arts replaced the College of Art and Crafts and opened specialized workshop departments, it was the first time art students had access to fully equipped video studios, post-production software, and digital cameras. As mentioned by Margrét, this resonates with questions asked by Egill Saebjornsson on equating the difference between actual and virtual worlds, with that of the different between nature and technology. At the Venice Biennale in 2017, Out of Control (2017), based on the characters of two trolls named Ūgh & Bõögâr, offered reflection on the ways that for more than a century, Icelandic art has been described as being grounded in nature: “The fusion of virtual and actual worlds, reality and fiction, encountered in Egill Saebjornsson’s work, also makes us question the distinction, not only between art worlds but just ‘worlds’. Today, the divide between contemporary art and media art, which characterized the past decades, has collapsed.” (329)

Coinciding with the publication of the book Digital Dynamics in Nordic Contemporary Art, edited by Tanya Toft Ag and published by Intellect Books, Margrét curated the online exhibition Arts New Representations which was launched on Saturday, June 13th on the platform of the Icelandic online magazine Artzine.is. The five works shown in the exhibition cultivate a sense of where Icelandic media art has been and where it is going with the current generation and with the impact of current global events. Alongside the exhibition was a panel discussion with Icelandic artists that offered further analysis of the direction and sensibilities of contemporary Icelandic digital art.

In Margrét’s discussion of the early years of LORNA, an association for electronic arts that she founded in 2002, she observed a certain skepticism towards digital technology and media art within the mainstream contemporary art scene. In recent years she has observed a change in attitude to a certain extent – the artists on the panel make it clear that this early skepticism is no longer valid when such erudite discussion concerning digital art and individual artistic practices. The artists on the panel, Geirþrúður Finnbogadóttir Hjörvar, Freyja Eilíf, Auður Lóa Guðnadóttir, and Fritz Hendrik Berndsen aka Fritz Hendrik IV, are part of the younger generation of artists obsessed with the split between the digital and non-digital in what could be referred to as a post-digital era. The discussion offered many valuable insights into the online exhibition from artists familiar with the concerns of the digital medium, for example, the overwhelming nature of the digital in our everyday life and how it becomes a tool both for fabrication and as a medium itself.

(Screenshot) Saemundur Thor Helgason’s Solar Plexus Pressure Belt Trailer, ‘Working Dead’

(Screenshot) Saemundur Thor Helgason’s Solar Plexus Pressure Belt Trailer, ‘Working Dead’

Saemundur Thor Helgason’s Solar Plexus Pressure Belt Trailer, ‘Working Dead,’ introduced the prototype of an anxiety-reducing device engineered and designed by the artist in collaboration with fashion designer Agata Mickiewicz. The work is a continuation of a larger project called ‘Félag Borgara’, (eng. Fellowship of Citizens) an interest group founded by the artist in Reykjavik in October 2017 with the aim of lobbying for basic income in Iceland through apolitical means. Solar Plexus Pressure Belt™, inspired by Saemundur Thor‘s own experiences as a creative practitioner suffering from anxiety and panic attacks in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, uses the digital medium as a platform for content as well as representation of its material embodiment. The Solar Plexus Pressure Belt™ combines elements of design and social activism in carrying out one of the earliest uses of the internet, that of using it as space where a truly democratic zone can transform certain elements of society. The design of the belt simulates a finger pressing into the solar plexus area, a motion and coping mechanism Saemundur Thor discovered would reduce feelings of stress and anxiety, offers a palliative solution to late capitalism.

Where Saemundur Thor investigates the body’s internalized reaction to feelings of stress and anxiety, Anna Fríða Jónsdóttir’s ‘Thought Interpreter’ is the artists’ abstracted example of the mirroring of systems that every person assimilates on scales ranging from smaller bodily systems to massive societal systems and beyond. It is a representation of the way we are all connected through our biological engineering, mostly made of water. The artist asks: “Since water is the world’s best solvent, could something very personal from every living resident be residing underneath the city in the sewer system? Are we creating a sub-city of thoughts and emotions mirroring reality, a reflection of the overall emotional state of a city?” ‘Thought Interpreter’ is akin to walking in on a conversation through a medium whose language is nonverbal, subliminal. In light of the current global pandemic, the reality of an invisible, molecular disease that is carried between individuals and has changed the structure of many ways in which we carry out everyday life, it seems even more plausible to imagine the ‘Thought Interpreter’ as representing the conversation happening between our body and the world around us on a personal and global level.

(Screenshot) Anna Fríða Jónsdóttir’s ‘Thought Interpreter’ ( 2012). Jars, bathroom tiles, spoons, 9 servo motors, arduino.

(Screenshot) Anna Fríða Jónsdóttir’s ‘Thought Interpreter’ ( 2012). Jars, bathroom tiles, spoons, 9 servo motors, arduino.

In this way, the digital medium allows both Anna Fríða and Saemundur Thor the possibility to explore reality in an impossible way by creating a scenario for a possible world, implementing it as a digital reality, and entering it for effect. It is for this reason that the term ‘cyberspace’ was first coined by a Science fiction author, William Gibson, as it is literally the realm where possible futures begin to be implemented.

In the panel discussion, Geirþrúður Finnbogadóttir Hjörvar mentioned the post digital’s relationship to the post-apocalyptic as a historical manner and political scheme in which the ideas, programs and grand schemes come into play in an ideological sensibility that is becoming more and more pessimistic:

“We have abandoned this sense of progress and we are just living this dystopic unfolding of futuristic stuff but none of it seems to have any meaning so this dystopian sensibility has become so strong… the most relevant post-digital is the post-apocalyptic. It seems like we thought there would be an event but instead, it’s just a steady decline that leads to nowhere. That’s the idea of post-apocalypse, if we don’t have a vision of a future collectively, that’s what’s on offer, nothing apocalyptic, because that would be an event, but it’s just that things don’t happen.”

(Screenshot) Ágústa Ýr Guðmundsdóttir aka Ice Ice Baby Spice

(Screenshot) Ágústa Ýr Guðmundsdóttir aka Ice Ice Baby Spice

Digital artist, Ágústa Ýr Guðmundsdóttir aka Ice Ice Baby Spice, readily embraces the digital realm as a studio, and as such, accepts the limitations of it as a zone of possibility for self-expression of her own anima through social media as well in her work digitizing fashion for casting directors and labels. The process of photographing, scanning, and editing brings many opportunities to investigate the aesthetics of the realm between the digital and the physical. When making videos, she uses a camera within a 3D world that she has made, and is using the same settings as a normal camera, moving it digitally instead of holding it physically.

In the panel talk, Geirþrúður, an artist from an earlier generation, also discussed how she has come to accept the digital world as her studio, however, she notes that the awe of what is possible that first overcame her in the first days of digital art affects how she looks at the materiality of the digital. Becoming recently interested in 3D modeling (which can be seen to great effect in her work featuring renderings of Real Estate advertisements), Geirþrúður said that the relief from physical law is a huge inspiration as she can decide to which degree what she creates in the digital space becomes material: “This also brings me to a sense of what is the materiality of the digital, so the more I get drawn into its immateriality, the more I also get interested in the materiality of the digital but also the materiality of real life, so it has this pretty intense dialectical relationship.”

This dialectical relationship between the two mediums is an eloquent conversation that is what makes the world(s) of digital art such a fascinating receptacle of processing how we live in the contemporary moment. Freyja Eilíf’s commentary in the panel discussion on what has intrigued her with the digital also relates to the processing of how we live in and of the digital in our everyday lives – she sees it as a hybrid reality that we are collaboratively creating with the digital realm: “I think of it as an alien, really, and something otherworldly. That’s what intrigues me about the internet. I also think about where it was before it became the internet. Was it just lying dormant?”

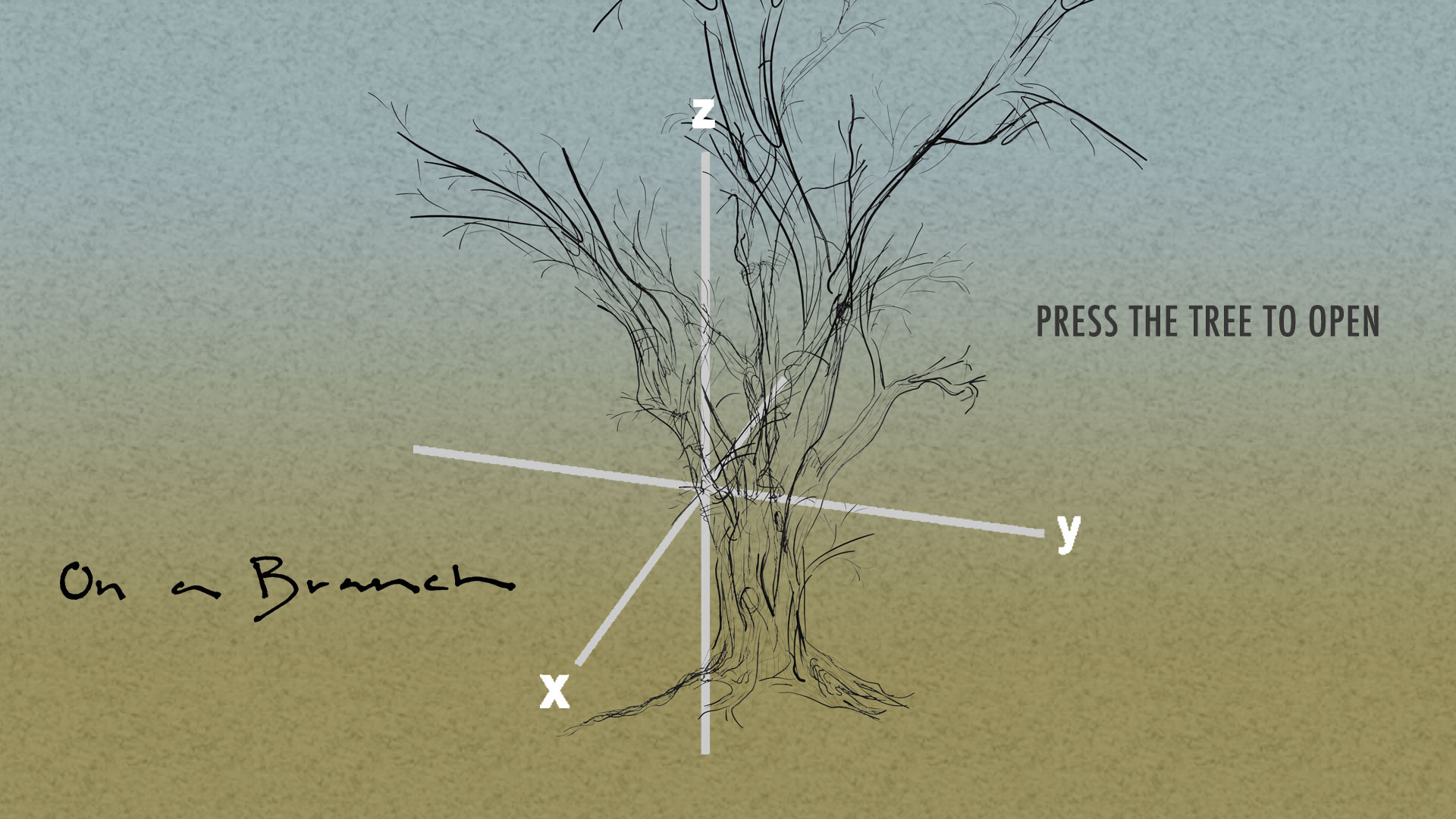

(Screenshot) Hákon Bragason, On a Branch, (2020)

(Screenshot) Hákon Bragason, On a Branch, (2020)

In a similar thread of questioning the space of communication within the digital, as well as the longevity of digital spaces and their mechanism as a component of time is digital artist, Hákon Bragason´s 3D interactive work. In ‚On a Branch,‘ viewers become visitors in a virtual realm with its own illuminating sun that gives the sensation of experiencing the sun from another planet. The transportive world´s hazy pink glow features a lone tree, sketched with branches reaching towards the sun. Here the artist is able to examine the presence of people within a 3D internet space where it is not possible to have normal communication and people only are made aware of the presence of others through the number of leaves that appear on the tree. The non-verbal realm literally goes out on a branch to examine how we communicate presence as well as the mode in which history is recorded in the digital.

(Screenshot) Haraldur Karlsson´s ´Snæfellsnes Broadcast Station´

(Screenshot) Haraldur Karlsson´s ´Snæfellsnes Broadcast Station´

In ´Snæfellsness Broadcast Station, Haraldur Karlsson reports live from Snæfellsnes, the artist playfully presents the surrounding landscape in which he has created a simple set up of a wooden chair. A child occasionally shares the screen, waving to observers. Interspersed with the landscape scenes and the overlay of different video warping effects are weather maps of the Snæfellsnes peninsula with dramatic overlays of fire-spitting and tornadoes swirling. The work is seemingly a commentary on the role of the Snæfellsnes peninsula in local lore: it is the place where French author Jules Verne begins his 1871 Science Fiction classic, Journey to the Center of the Earth, with entering a dormant volcano. The peninsula is also known for its heavy mythology of elven lore or ´Hidden People´. The lore attached to this geographic location in Iceland is now part of every marketing campaign introducing tourists to the area.

In the panel talk, Fritz Hendrik Berndsen discusses the way in which Icelandic art history is full of landscape paintings created before the digital marketing of Iceland to tourists began, but it´s also where it began because Icelandic painters did not appreciate the value of the landscape before Danish poets began writing about their majesty. In ´Snæfellsnes Broadcast Station,´ Haraldur portrays a landscape being consumed by the digital, however, it is not only happening on a consumer level, but as part of surveillance culture. “The Icelandic landscape has a completely different meaning after Google Earth appears because now, you’re not alone in nature,” added Geirþrúður in the panel discussion, “there’s always a satellite above you.”

In the context of Haraldur´s previous work with themes of expressing a holistic philosophy of science and art in which art reflects reality in its relation to man, the artist is the anti-hero, using the medium to be more human. There‘s always a Google Earth satellite even in the most isolated landscapes, making the world more known, and giving with it a „human angle“ permeated with the factors of being human, which also means seeing it, as Haraldur does with video editing software, through the historical prism of science and philosophy.

Erin Honeycutt

Photos: courtesy of the artists.

Acknowledgement: This text is commissioned by the project Digital Dynamics: New Ways of Art based on the book Digital Dynamics in Nordic Contemporary Art

(Intellect, 2019) and supported by the Nordic Culture Fund and Nordic Council of Ministries. www.digitaldynamics.art„

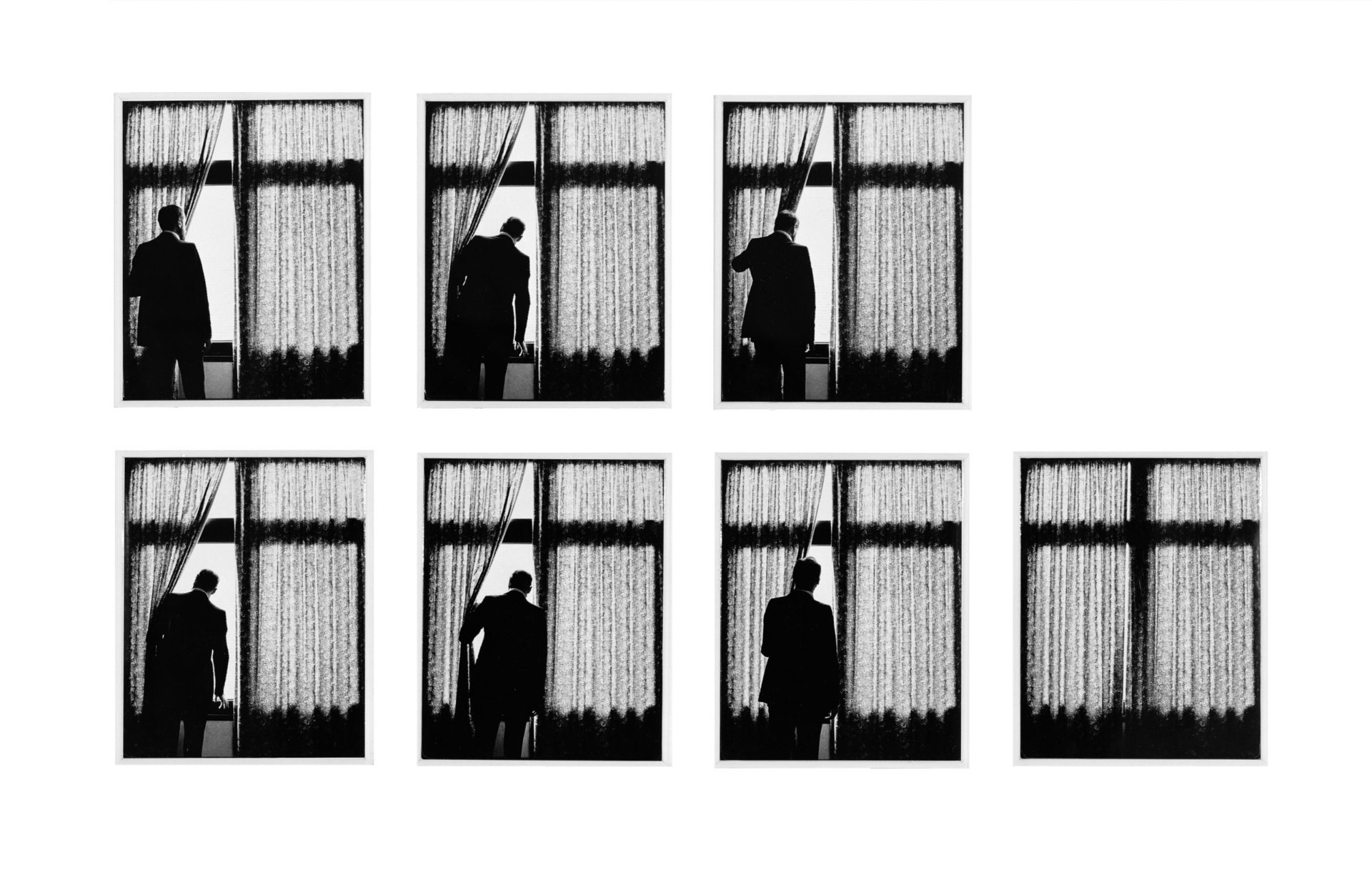

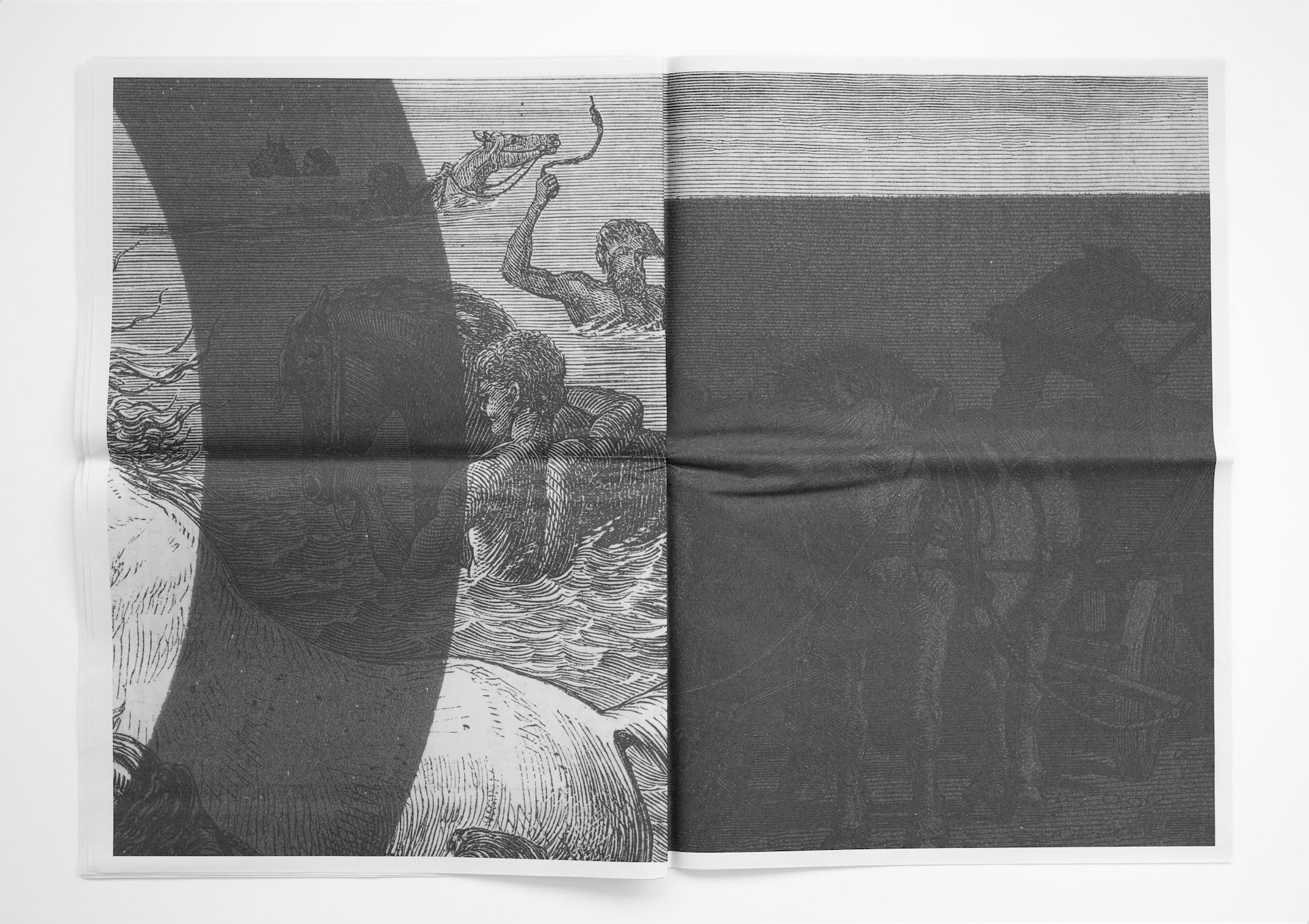

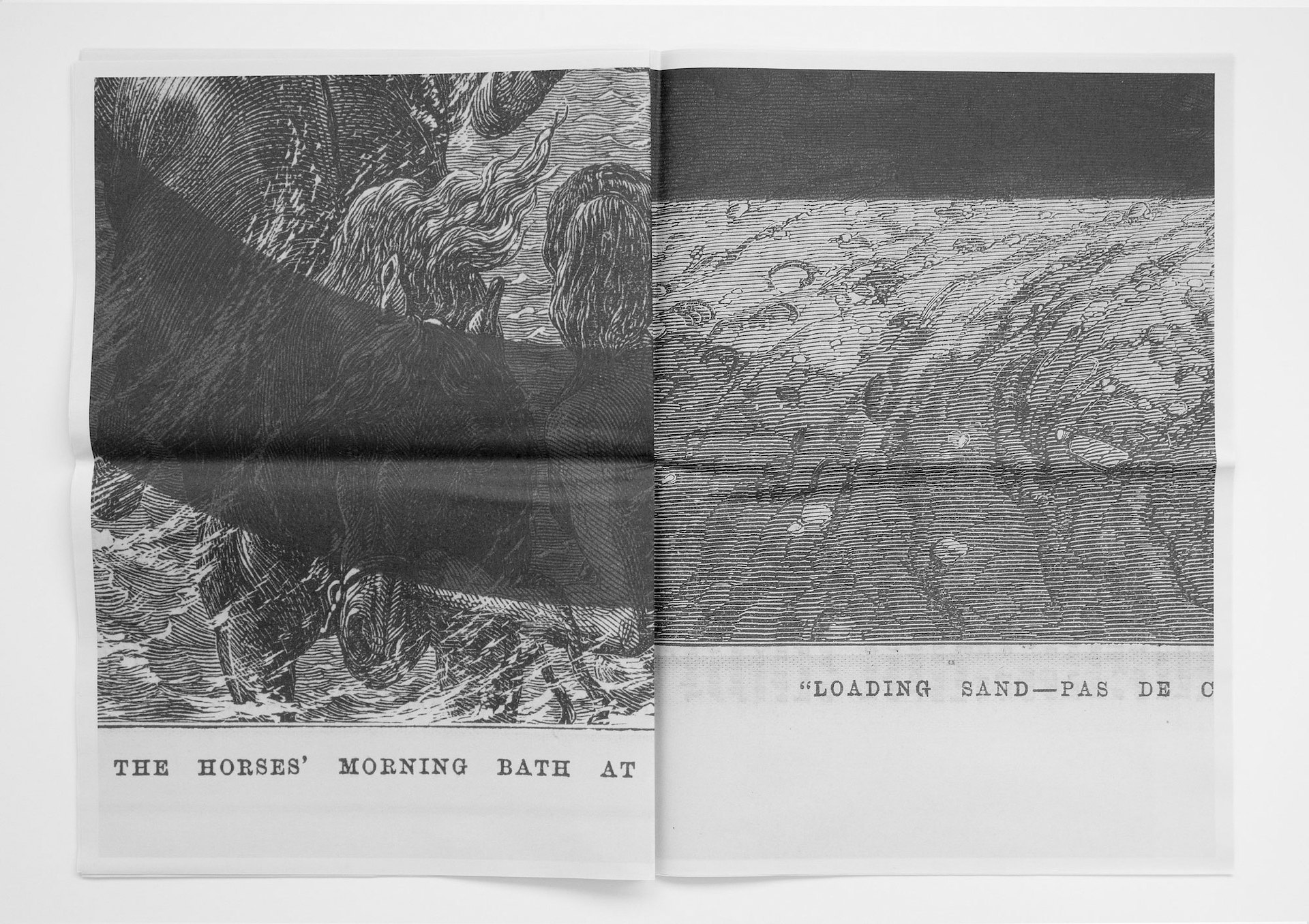

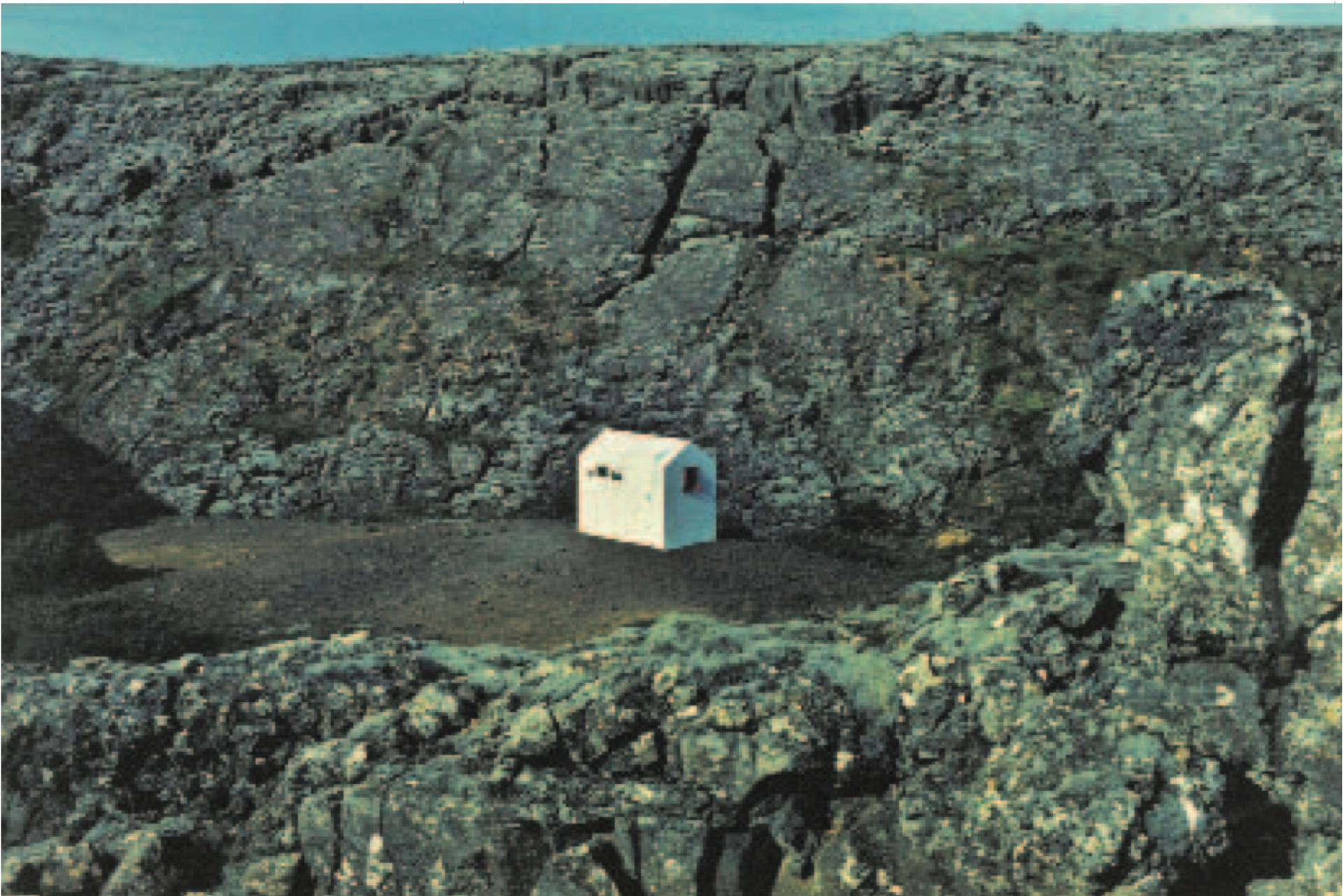

HREINN FRIÐFINNSSON A View in A (1), 1976 black and white photograph 52.5 x 64.5 cm. Courtesy of i8 gallery.

HREINN FRIÐFINNSSON A View in A (1), 1976 black and white photograph 52.5 x 64.5 cm. Courtesy of i8 gallery.