Listin og aktívisminn – Töfrafundur áratug síðar

Listin og aktívisminn – Töfrafundur áratug síðar

„Töfrafundur – áratug síðar” var yfirskrift sýningar þeirra Libiu Castro og Ólafs Ólafssonar sem stóð yfir í Hafnarborg frá 20. mars til 31. maí s.l. Sýningin var beint framhald gjörningsins „Í leit að töfrum – Tillaga að nýrri stjórnarskrá fyrir lýðveldið Ísland” sem sameinaði tónlist, myndlist og kröfugerð um innleiðingu nýju stjórnarskrárinnar og fluttur var 3. október 2020 í Listasafni Reykjavíkur Hafnarhúsi, á götum úti við Stjórnarráðið og Alþingi Íslands. Gjörningurinn sem er einn eftirminnilegasti listviðburður síðasta árs var unninn í samstarfi við Listahátíðina Cycle og Listahátíð í Reykjavík en var einnig risavaxið samstarfsverkefni þeirra Libiu og Ólafs við sýningastjórana Guðnýju Guðmundsdóttur í Berlín og Sunnu Ástþórsdóttur í Reykjavík, Stjórnarskrár félagið og Félag kvenna um nýja stjórnarskrá auk fjölda annara svo sem aðgerða- og umhverfissinna, tónskálda, tónlistafólks og grafíklistamanna. Fyrir þetta verk hlutu höfundarnir Íslensku myndlistarverðlaunin 2020.

Sýningin í Hafnarborg núna í vor var yfirlit verka þeirra síðasta áratuginn sem eiga það sammerkt að fjalla um stjórnarskrárnar. Þessi verk eru þó ekki fyrstu verk tvíeykisins sem hafa pólitíska eða félagslega skírskotun enda hafa félagsvísindi, pólitík, samtal og samvinna við aðra listamenn, félagsvísindafólk og fræðimenn ávallt fléttast inn í list þeirra. Gjörningurinn “Í leit að töfrum” hefur þó sennilega sprengt met þeirra í fjölda samstarfsaðila því að þessum stórbrotna myndlistar-, tónlistar- og aðgerðarsinnagjörningi komu vel yfir 150 listamenn og aðgerðarsinnar.

Í gjörningnum var port Hafnarhússsins, Listasafns Reykjavíkur nánast þakið máluðum, áprentuðum og ísaumuðum textílverkum í formi áróðurstengdra borða og fána, auk þess sem stórar diskókúlur og lýsing ýfðu upp stemninguna sem var í senn hátíðleg, blönduð fögnuði, von og baráttugleði. Hver tónlistamaður eða tónlistahópur flutti sína kafla af tónlist hér og þar í salnum allt frá pönkútsetningum til klassískra kammertóna, raftónlistar og kórverka. Verkin voru ýmist sungnir, talaðir, rímaðir eða rappaðir stjórnarskrár kaflar, flestir fluttir á íslensku, en líka á pólsku, ensku og grænlensku auk þess sem barnakór, popparar og þjóðlagatónskáld tróðu upp.

Eftir um fjögurra klukkustunda gjörning í safninu voru risavaxnir borðarnir bornir út þar sem hópur fólks, bæði úr Stjórnarskrárfélaginu, Samtökum kvenna um nýja stjórnarskrá, náttúruverndarsamtökum, listamenn og aðrir aktívistar tóku þátt í að ganga með borðana hrópandi kröfur sínar í takt við gjallarhornið sem glumdi í forgrunni. Gengið var frá Listasafninu að Stjórnarráðinu þar sem staldrað var við en endað við Alþingishúsið þar sem skærbleikir risaborðarnir sem mynduðu setninguna „Nýju stjórnarskrána takk!” voru hífðir upp með krana framan við þinghúsið. Skilaboðin einföld en eins og risavaxin upphrópun fyrir þingheim og almenning að vera minnt á að þjóðin á nýja stjórnarskrá.

Myndband með „Aðfaraorðum“ Lag og söngur: Lay Low.

Sýningin í Hafnarborg

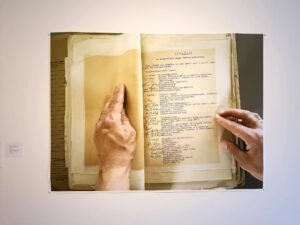

Sýningin í Hafnarborg var stór myndbandsinnsetning sem lýsir ferli verkanna síðasta áratuginn ýmist í formi heimilda úr fréttum eða gjörningum um efnið, endurbirting muna svo sem á upprunalegum handritum stjórnarskránna frá 1874, 1920 og 1944 og tillögu Íslendinga frá 1873. Sýningin var einni vörðuð ýmsum þáttum sem tengdist gjörningnum í byrjun október svo sem textílverkunum/borðunum, skissum unnum fyrir gjörninginn og litskrúðugum stærri myndverkum sem lýstu tónlistabræðingnum. Einnig mátti þar finna potta og pönnur sem minntu okkur á búsáhaldabyltinguna sem nýja stjórnarskráin spratt upp úr.

Í innra rými sýningarinnar sem vísaði til stofu í heimahúsi með sjónvarpi og fjarstýringu mátti setjast niður og leita að völdum köflum myndbandsins. Sýningin tók ýmsum breytingum yfir sýningartímann en samhliða henni var rekinn pop-up markaður á silkiþrykktum bolum og varningi með slagorðum. Auk þess voru settar upp vinnustofur – Töfrasmiðja – með prent- og saumaverkstæði og fundaraðtöðu fyrir aktívista. Þá var hengt upp verk á gafli Hafnarborgar sem seinna var fjarlægt og svo hengt upp aftur en það olli miklu fjaðrafoki innan bæði stjórnmála- og myndlistaheimsins.

Artzine ræddi við þau Líbíu og Óla um stjórnarskrárverkin og þann tíu ára feril sem leiddi til sýningarinnar í Hafnarborg, gjörninginn sem færði þeim myndlistarverðlaunin og samtalið milli listar og aktívismans síðasta áratuginn sem inniheldur baráttu þeirra fyrir nýrri stjórnarskrá.

Artzine hitti þau Libiu og Ólaf og spurði þau hvaðan þessi mikla samvinnugleði sprettur og hvaðan áhuginn á því að vinna með pólitísk álitamál í myndlistinni kemur.

Libia: „Við höfum orðið fyrir áhrifum úr ýmsum áttum. Við heilluðumst sérstaklega af suður amerískum listamönnum, m.a. frá Chile frá sjöunda og áttunda áratugnum og af Neo-concretista hreyfingunni í Brasilíu. Einnig hrifumst við af Fluxus sem alþjóðlegri myndlistahreyfingu sem brúaði vestrið og Asíu. Staðan fyrir þann tíma í Evrópu var okkur einnig mjög hugleikinn í gegnum aðferðir Situationistanna en þeir voru bæði félagshyggjulega og pólitískt þenkjandi auk þess að koma úr fjölbreyttum áttum. Þar varð ævinlega til samtal mismunandi listamanna t.d. myndlistarmanna við ljóðskáld og arkitekta. Ef maður er að vinna með lífið og umhverfið út frá gagnrýnum félagshyggjulegum nótum þá er ekki hægt að horfa bara út frá einum fleti eða sjónarhorni. Það beinlínis kallar á samvinnu úr ýmsum áttum. Útkoman verður þá ekki eingöngu bundin myndlist heldur verður til víðara samtal svo sem samtal milli listarinnar við heimspekina, við sviðslistirnar, við blaðamennskuna og fleiri greinar”.

Ferill hugmynda og verka?

Libia: „Við hófum vinnuna við stjórnarskrárverkin árið 2007 – útfrá þeirri hugmynd að gera innihald gömlu stjórnarskrárinnar opinbert og sýnilegt. Fyrri hluti þess verks var þá frumflutningur á tónlistargjörningi í Ketilhúsinu á Akureyri í mars 2008 sem liður í sýningunni Bæ, bæ Ísland í Listasafninu á Akureyri en við höfðum fengið tónskáldið Karólínu Eiríksdóttur til að semja í samstarfi við okkur tónverk við alla núgildandi stjórnarskrá.“

Ólafur: „Á þessum tíma hófum við samningaviðræður við RÚV um hvort áhugi væri fyrir því að sjónvarpa verkinu beint en svo reyndist ekki vera. Einhver áhugi hafði þó kveiknað og hafði fréttastofa RÚV samband við safnið í kjölfar flutningsins og óskað eftir myndbroti sem svo var sýnt í fréttunum. Í áratugi hafði myndlist nær eingöngu verið sýnd í lok fréttatíma sem enda innslag eða niðurlag frétta og textinn jafnvel runnið yfir listina með undirspili úr frægum kvikmyndum.

Við vorum því nokkuð ánægð með að fá pláss í sjálfum fréttatímanum og þótti það fréttnæmt í sjálfu sér. Eftir þetta hafði RÚV samband við okkur og vildu fá að flytja verkið í heilu lagi í útvarpi. Við höfnuðum því þar sem við vildum reyna áfram að fá verkinu sjónvarpað og töldum að það gæti dregið úr líkunum á að fá það í gegn ef verkið hefði verið flutt í heild sinni í útvarpi. Að endingu samþykktum við gerð langs útvarpsþáttar sem byggðist einnig á viðtölum við okkur og Karólínu. Hluti af tónlistinni hennar varð svo þematónlist þáttar sem Ævar Kjartansson og Jón Ormur gerðu seinna um stjórnarskrárnar.“

Libia: „Árið 2011 gerðum við svo annan hluta verksins en á þeim tíma var búið að kalla saman stjórnlagaráð og skrifin við nýju stjórnarskrána hafin. Ólöf K. Sigurðardóttir hafði boðið okkur að vera með einkasýningu í Hafnarborg og við ákváðum að leita aftur eftir samstarfi við RÚV sem í þetta sinn gekk eftir. Við tókum verkið upp í samstarfi við sjónvarpið í myndveri RÚV og var það bæði sýnt í Hafnarborg og því sjónvarpað. Á þeim tíma var áhuginn fyrir stjórnarskránni orðinn meiri í samfélaginu. Þá hjálpaði það til að við værum fulltrúar Íslands á Feneyjartvíæringinn þetta sama ár.

Fundurinn í Gerðarsafni 2017 var svo haldinn á fimm ára afmæli þjóðaratkvæðagreiðslunnar um nýju stjórnarskrána á samsýningunni Sovereign | Colony sem Listahátíðin Cycles stóð fyrir en þar sýndum við frumrit stjórnarskránna frá 1874, 1920 og 1944, ásamt prentaðri útgáfu af dönsku stjórnarskránni frá 1849, fjölrituðu eintaki af nýju stjórnarskrártillögunni frá 2011 og fl. Þetta urðu ákveðin tímamót hjá okkur einnig því þarna leggjum við grunnin að áframhaldandi vexti verksins. Við heilluðumst líka af umrótinu sem nýja stjórnarskráin spratt upp úr en pólitíski jarðvegurinn sem hún verður til í er svo gjörólíkur þeim sem sú gamla kemur úr. Hún verður til í eftirleik hrunsins, samin af stjórnlagaráði, 25 manna margbreytilegum vinnuhóp sem var kosinn til verksins af almenningi. Fundurinn í Gerðarsafni átti að spegla það og innihalda mismunandi raddir en við buðum stjórnmálafólki og listafólki til fundarins að ræða innihald og samanburð nýju og gömlu stjórnarskrárinnar. Okkur langaði að halda nýju stjórnarskránni á lofti og sjá til þess að hún félli ekki í gleymsku strax.

Það hefur verið stöðug barátta stjórnarskrárfélagsins að halda nýju stjórnarskránni á lofti með markvissum aðgerðum og stemma stigu við þögguninni sem hefur átt sér stað í samfélaginu gagnvart henni. Verkin okkar eru hluti af þeirri baráttu. Við gengum til liðs við Stjórnarskrárfélagið á sínum tíma og fórum samhliða því að þróa þá hugmynd að setja alla krafta okkar í að vinna að framgangi nýju stjórnarskrárinnar. Setja hana í tónlistarlegan búning og kallast þannig á við verkið sem við gerðum með gömlu stjórnarskrána.“

Textílverk eða áróðurfánar?

Ólafur: „Vísirinn að þessari textílmaníu, varð eiginlega til þarna í Gerðarsafni 22. september 2017 þegar við málum textann „20. Október 2012” á vegginn. Dagsetningu þjóðaratkvæðagreiðslunnar um nýju stjórnarskrána. Á sýningunni okkar í Hafnarborg sýndum við „textílverkin” okkar sem í öðru samhengi kallast „bannerar” eða „áróðursfánar”. Í upphafi máluðum við á vegginn en fórum svo að mála með akrýlmálningu á textíl. Við færðum því kjurra veggjalist yfir í hreyfanlega textíllist sem svo sprakk út í allskyns textílverkum, saumuðum, máluðum og þrykktum. Ég talaði oft um textílverkin okkar sem „bannera” sem er ekki hugmynd úr listheiminum svo núna er ég meðvitað farinn að vísa til þeirra einnig sem textílverka, sem þau líka eru.“

Tónlistarleg hámenning og lágmenning:

Ólafur: Í vinnunni með gömlu stjórnarskrána ákváðum við að nota klassíska nútímatónlist og þá annars vegar þar sem form hennar er svo teygjanlegt. Þannig getur t.d. tímarammi slíks verks auðveldlega spannað 8 blaðsíður af texta. Hinsvegar höfum við lengi vel skipt menningunni í há- og lágmenningu og þar sem klassísk tónlist hefur jafnan flokkast undir hina svokölluðu „hámenningu” þá ákváðum við að nota klassíska nútímatónlist. Í ljósi innihaldsins og virði þess fyrir samfélagið var það meðvituð ákvörðun að nota svona gildishlaðna „hámenningarlega” tónlistartegund. Karólína valdi í samtali við okkur að semja verkið bara fyrir píanó, kontrabassa, tvo einsöngvara og kór. Í gjörningnum í október vildum við svo hafa aðra nálgun. Okkur tókst ekki að hafa allar mögulegar tegundir tónlistar innan verksins, ha, ha…. Þá unnum við með fjölda tónskálda auk þess að reyna að innvikla eins mikla samvinnu og samtal inn í verkið og hægt var.

Libia: Við byrjuðum að vinna með níu tónskáldum, bjuggum til þrjá hópa með þremur í hvorum svo tónskáldin áttu líka sitt innbyrðis samtal. Svo ákváðum við í sameiningu að tónsmiðirnir fengju tilfallandi greinar til að vinna með, úr hinum ýmsu köflum stjórnarskrárinnar, þannig að verk þeirra fléttuðust saman, en endanlegur flutningur var þó línulegur.

Faraldurinn:

Ólafur: Þegar við hófumst handa við að vinna að gjörningnum í Berlín og þegar við vorum að prufukeyra fyrstu hugmyndir tónsmiðanna á Íslandi haustið 2019 höfðum við ekki hugmynd um það sem koma skyldi. Upphaflega vorum við að hugsa um að gjörningurinn gæti rúmað þátttöku allt að 800 manns auk almennings. Seinna vorum við komin með spurninguna um hvort við gætum yfir höfuð framkvæmt þetta vegna Covid faraldursins.

Libia: „Það er í raun ekki hægt að horfa á verkið án þess að setja það í samhengi við Covid. Það hefur verið krefjandi í þessu ferli að vinna í kringum það. Við þurftum að breyta ýmsu vegna faraldursins en við náðum þó að halda í þá grunnþætti sem við vildum. Uppsetning verksins hélt flæðinu sem við höfðum hugsað okkur en var líka ákveðin málamiðlun þar sem dregið var úr ýmsu og við þurftum auðvitað að takmarka hópa áhorfenda í ákveðin tímahólf. Þá var verkinu einu sinni frestað og dagsetningin færð frá júní fram í október og næstum einnig frestað þá, en við ákváðum að halda okkar striki.“

Samvinnan og stærðarskalinn?

Libia: „Ferlið við gjörninginn var unnið með sýningarstjórunum Guðnýju Guðmundsdóttur sem hefur tónlistarlegan bakgrunn og er framkvæmdastjóri Cycle listahátíðarinnar og Sunnu Ástþórsdóttur í Reykjavík sem hefur sinn bakgrunn í listfræði og starfar á Nýlistasafninu. Ferlið var bæði skipulega unnið og kaotískt í senn. Í upphafi vorum við bara fjögurra manna teymi en svo förum við að vera í sambandi við tónskáldin og tónlistarfólkið, Listasafn Reykjavíkur, sjónvarpið og svo auðvitað aktívistana og aðstoðarfólk svo þetta var stundum dáldið brjálað. Covid kallaði auðvitað líka yfir okkur þetta dásamlega kaotíska ástand. Þá var samvinnan á fjölbreyttum grunni og mikil samskipti sem urðu á köflum yfirþyrmandi en þetta var líka ferli sem tók tvö og hálft ár í vinnslu.

Þar sem við erum að vinna með lifandi ferli þá á verkið sér einnig sitt sjálfstæða líf. Verkið krefur okkur um að vinna á þessum stærðarskala því málið sjálft er samfélagslega á þessum stærðarskala. Við erum að tala um lög og grunnstoðir þjóðríkis. Stjórnarskrárfélagið er lífræn hreyfing sem hefur þurft að glíma við þöggun og þá jafnvel minkað en svo aftur stækkað á víxl. Þetta er eðli aktívismans. Hreyfingar þróast og breytast og á einum tímapunkti geta verið fimm einstaklingar að þrýsta á og halda uppi málstaðnum en svo getur allt sprungið. Okkur fannst að listræna upplifunin yrði að vera eins almenn og stór og hægt væri. Við vorum að ramma gjörninginn inn innandyra í safninu í þessu myndræna formi með því að líkja eftir stóru tónleikahúsi en svo var ekki síður mikilvægt að yfirgefa safnið og halda áfram á götum úti í almannarýminu”.

Aktívismi eða list?

Ólafur: „Skilgreiningin á því hvað sé list og hvað ekki er ekki til sem eitthvað endanlegt og formfast og sama á við um aktívisma. List er alltaf í endurmótun og tilvist hennar byggir á samhengi við menningu, hugmyndafræði, valdastrúktúr og valdaforræði hvers tíma í sögulegu samhengi. Hún er bara eitthvað sem við finnum upp á, viðhöldum, breytum, brjótum upp, berjumst fyrir, storkum eða enduruppgötvum jafnóðum“.

Libia: „Þetta er raunar bæði list og aktívismi sem getur vel gengið samtímis. Það er nauðsynlegt að láta ekki draga úr sér móðinn vegna einhverra strangra skilgreininga sem tíðarandinn setur manni hverju sinni heldur halda áfram að spyrja og storka listinni í gegnum reynsluna og verkin sjálf. Listin er niðurstaða þess samkomulags sem tíðarandinn setur okkur en hún er líka verkfæri til að endurspegla hann og jafnvel gagnrýna hann og ásamt öðrum greinum og fræðisviðum spyrja spurninga og reyna að hafa áhrif til breytinga”.

Þöggun eða ritskoðun?

Ólafur: „það má velta vöngum yfir ýmsum þáttum þegar kemur að fjölmiðlum og þeirri athygli eða kannski stundum fálæti sem sumir fjölmiðlar sýndu á ýmsum stigum í vinnuferli okkar með stjórnarskrárnar. Það má einnig velta því fyrir sér hvort sjónvarpsmiðlarnir þurfi ekki að taka meiri þátt í að starfa með myndlistarfólki og móta sér þar skýrari stefnu. Kannski þurfa allar menningastofnanir að átta sig betur á hlutverki sínu við að miðla og styrkja list því innihald verka sem á einhvern hátt eru samfélagsádeila eða hafa pólitíska skírskotun eiga ekki að vera sniðgengin eða þögguð niður af ótta við að stofnanirnar sjálfar séu að taka málefnalega afstöðu.

Listafólk verður að hafa frelsi í sinni listsköpun svo lengi sem ekki er farið yfir ákveðin siðferðisviðmið. Við göngum ekki svo langt að segja að verk okkar hafi verið ritskoðuð af fjölmiðlum en mörgum þótti stundum grunsamleg þögn í kringum ákveðna hluta þessara verka. Sýningin í Hafnarborg hefur þó óumdeilanlega orðið fyrir ritskoðun því sunnudaginn 2. Maí var textílverk sem við hengdum á gafl Hafnarborgar samkvæmt leyfisveitingu verið fjarlægt. Verkið var uppstækkuð eftirmynd eins af þjóðfundarmiðunum, nú víðfrægu, frá þjóðfundinum 2010 sem innihélt eftirfarandi skilaboð til þingheims „EKKI KJAFTA YKKUR FRÁ NIÐURSTÖÐUM STJÓRNLAGAÞINGS”. Okkur var tilkynnt símleiðis um morguninn frá starfandi forstöðumanni Hafnarborgar að bæjarstjóri Hafnarfjarðar Rósa Guðbjartsdóttir hefði fyrirskipað að verkið yrði samstundis tekið niður.

Þegar við svo mættum á staðinn skömmu síðar var þegar búið að fjarlægja verkið án nokkurs samráðs. Við sáum okkur ekki annað fært en að kalla til lögreglu og tilkynntum um hvarf verksins þar sem engin ummerki voru lengur um það eða hvar það væri niðurkomið. Verkinu var síðar skilað til okkar af bæjarstarfsmanni en skilaboðin skýr. Verkið skyldi ekki hanga uppi.

Þessi aðgerð og aðför að listinni er auðvitað stóralvarleg en við höfum sýnt um allan heim, jafnvel á Kúbu og í Tyrklandi og höfum aldrei orðið fyrir álíka uppákomu af hendi stjórnvalda. Málið fór fyrir bæjarráðs- og bæjarstjórnarfundi í Hafnarfirði og eftir yfiirlýsingar frá Íslandsdeild ICOM, BÍL og fleiri aðila fékkst verkið hengt upp á ný en tveimur vikum síðar”.

Eftir að sýningunni í Hafnarborg lauk hóf textílverkið víðfræga „EKKI KJAFTA YKKUR FRÁ NIÐURSTÖÐUM STJÓRNLAGAÞINGS” í hringferð um landið, m.a. til Ísafjarðar og Akureyrar.

María Pétursdóttir

Ljósmyndir: María Pétursdóttir, Myndband / Video Libia Castro & Töfrateymið / The Magic Team.