Gjöfin til íslenzkrar alþýðu

Gjöfin til íslenzkrar alþýðu

„Menn vita ekki að þróun listgreina í landinu er meira og minna einum manni að þakka. Manni sem eitt sinn átti sér draum og nú er að rætast að fullu. Manni sem heitir Ragnar Jónsson og kenndur er við Smjörlíkisgerðina Smára.“

Svo mælti Kristján Davíðsson um vin sinn og bakhjarl Ragnar Jónsson í viðtali við Ingólf Margeirsson sem birtist í bók Ingólfs um Ragnar árið 1982. Þetta eru orð að sönnu enda markaði Ragnar djúp spor í menningarlífinu á liðinni öld. Hann átti þátt í því að lyfta tónlistarlífinu í Reykjavík upp á annað plan, hann gaf út bækur af miklum móð og svo keypti hann myndir af listamönnum, bæði af sýningum og beint af vinnustofum þeirra. Flest áhugafólk um myndlist þekkir ef til vill til gjafar Ragnars á listaverkum sínum til Alþýðusambands Íslands. Eftir rúmlega þriggja áratuga söfnun gaf Ragnar ASÍ um 120 verk sem skyldu verða grunnur að alþýðusafni sem hefði þann tilgang að mennta íslenska alþýðu í málaralist.

Stóran hluta af stofngjöf Ragnars má skoða á sýningunni Gjöfin til íslenzkrar alþýðu sem er samstarfsverkefni Listasafns Árnesinga og Listasafns ASÍ, en sýningarstjóri er Kristín G. Guðnadóttir. Þrír salir safnsins (af fjórum) fara undir sýninguna auk þess sem þrjú verk eru í miðlægu aðalrými safnsins. Á sýningunni eru alls 52 verk eftir fimmtán listamenn til sýnis, það elsta frá 1906 en yngstu verkin er frá um 1960.

Verkin í hverjum sal fyrir sig fylgja lauslega skilgreindu þema. Þannig eru verkin í fyrsta salnum að mestu leyti landslagsverk, verkin í öðrum salnum mannamyndir og verkin í þriðja salnum eiga það sammerkt að vera tjáningarrík verk „þar sem áherslan er lögð á upplausn formsins og sprengikraft litanna,“ líkt og segir í sýningarskrá. Í aðalrýminu má svo finna tvær blómauppstillingar og stórt olíuverk Kjarvals, Hellisheiði.

Uppsetning sýningarinnar er að mestu í takt við verkin, sígild. Málverkunum er raðað eftir miðlínu á hvíta veggi, sem er viðbúið. Á sýningunni má samt sem áður finna áhugaverðar undantekningar á þessari reglu. Útfærslan á mannamyndunum í sal tvö er gott dæmi um slíka undantekningu. Á rauðum endavegg má finna sjálfsmyndir fimm listamanna og á aðliggjandi vegg vinstra megin má finna tvær portrett myndir af listamönnum sem eiga verk á sýningunni, þeim Þorvaldi Skúlasyni og Nínu Tryggvadóttur. Gegnt Nínu og Þorvaldi er svo mynd af Ragnari sjálfum á hvítum vegg, máluð af Jóhannesi Kjarval. Með þessari uppsetningu og litavali tekst sýningarstjóranum vel að hópa listamennina saman, en miðlínu er sleppt og neðri hluti hvers ramma stendur á sameiginlegri línu. Listamennirnir eru þar með allir á sama stalli. Ragnar stendur þannig fyrir utan hópinn auk þess sem mynd hans hangir er látin hanga ögn hærra á veggnum sem undirstrikar hlutverk hans sem velgjörðarmanns.

Sá listamaður sem átti flest verk í safni Ragnars var Jón Stefánsson.

Sá listamaður sem átti flest verk í safni Ragnars var Jón Stefánsson.

Mannamyndir voru mikilvægur hluti af safni Ragnars.

Mannamyndir voru mikilvægur hluti af safni Ragnars.

Það má þó deila um þá ákvörðun að láta Ragnar hanga hærra uppi heldur en listamennina sjálfa. Við lestur á því sem skrifað hefur verið um persónu Ragnars má skilja það sem svo að hann hafi verið yfirlætislaus maður og seint viljað trana sér fram. Því til stuðnings verður hér aftur vísað til spjalls þeirra Ingólfs Margeirssonar og Kristjáns Davíðssonar, en Kristján kemst svo að orði um Ragnar: „[H]ann vill láta verk sín líta út sem sjálfsagaða hluti þar sem nafn hans kemur hvergi fram. Hann vill vera, en ekki sýnast eða sjást.“ Í þessu samhengi má auk þess minnast sögunnar af því þegar afhending stofngjafarinnar fór fram í Listamannaskálanum samhliða opnun sýningar á stórum hluta gjafarinnar. Mikill fjöldi tiginna gesta var viðstaddur, en í hópnum var Ragnar hvergi að finna, heldur færði Tómas Guðmundsson ASÍ verkin formlega fyrir Ragnars hönd. Það má því færa rök fyrir því að Ragnar hefði sjálfur kosið gegn því að vera settur ofar listamönnunum.

Aðra undantekningu á miðlínu og hvítum veggjum má finna í sal þrjú. Á dökkgráum vegg sem blasir við gestum þegar þeir ganga inn í salinn hanga tólf abstrakt verk sex listamanna í salon upphengi. Veggurinn brýtur rýmið upp á hrífandi hátt og útfærslan virkar vel. Sýningargestir taka kannski fyrst eftir því í sal þrjú að verk einstakra listamanna eru ekki sérstaklega látin hanga hlið við hlið og strangri tímaröð er ekki heldur fylgt. En það sem mestu máli skiptir er það að uppsetning sýningarinnar er fyrst og fremst rökrétt – þau verk sem valin eru til þess að hanga hlið við hlið virka saman.

Á sýningunni er auðvelt að nálgast upplýsingar um nafn listaverks, höfund og ártal og við hlið margra þeirra má auk þess finna stutta texta. Kjarni þessara texta eru tilvitnanir í listamenn, Ragnar sjálfan eða í bækur Björns Th. Björnssonar um íslenska listasögu og eru textarnir skemmtileg viðbót við sýninguna. Prentun textanna og merkinganna hefði þó mátt vera betri, svo virðist sem prentað hafi verið á hálfglæra miða sem límdir eru beint á vegginn. Fyrir vikið varð textinn ekki jafn læsilegur og sambærilegir textar sem prentaðir eru á hvít spjöld. Þá vantaði töluvert upp á yfirlestur textanna sjálfra og í þeim mátti finna nokkrar villur.

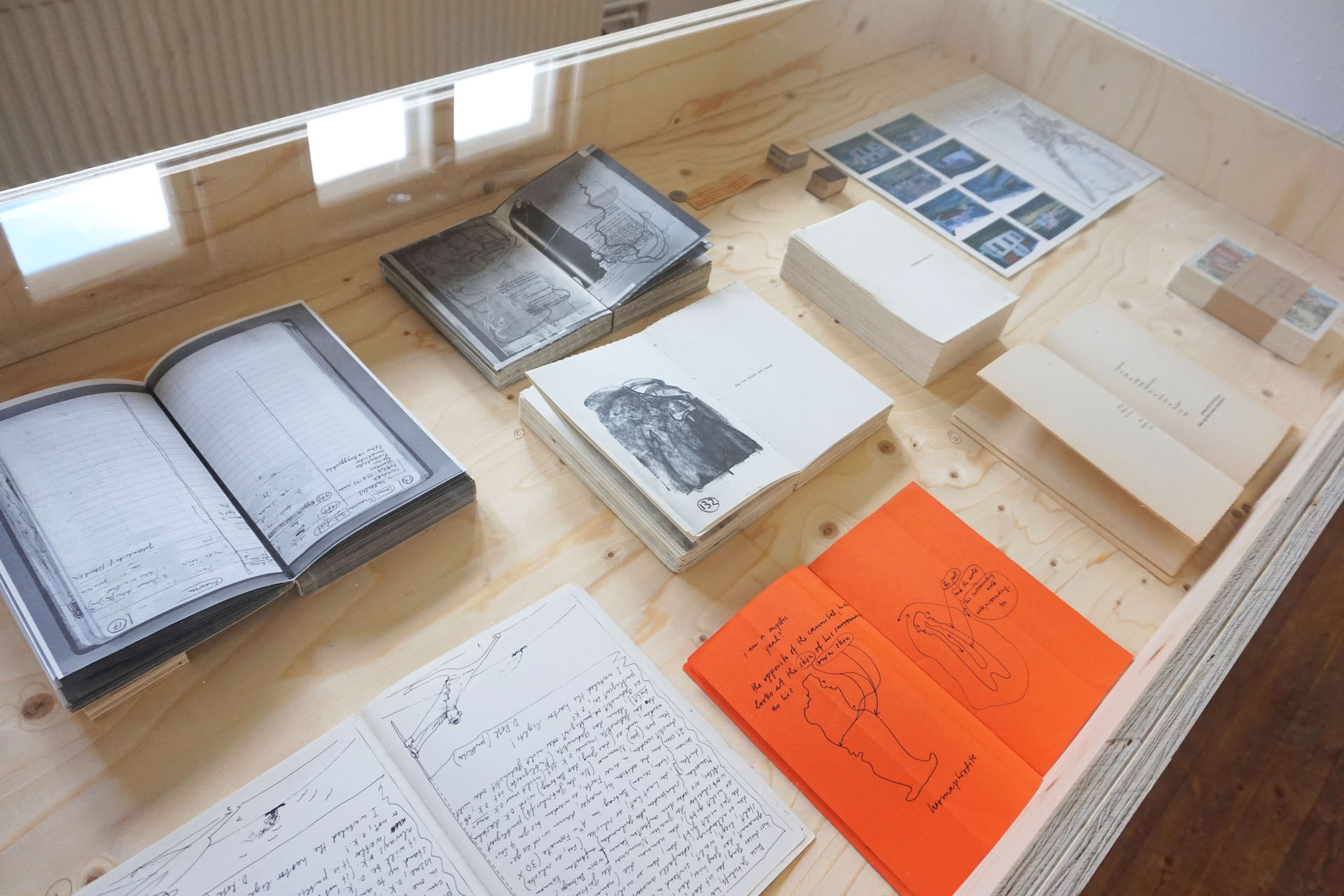

Samhliða sýningunni kom út vegleg bók um stofngjöf Ragnars. Í henni má finna myndir af öllum verkunum sem Ragnar færði ASÍ, bæði stofngjöfina frá árinu 1961, sem telur um 120 verk, og svo síðari viðbætur. Í heildina færði Ragnar ASÍ 147 verk. Auk myndanna má finna í bókinni fínan texta sem Kristín G. Guðnadóttir sýningarstjóri tók saman.

Það er vafalaust krefjandi verkefni að setja upp sýningu á verkum úr safneign eins manns. Sýningin getur, eðli málsins samkvæmt, ekki gefið sannfærandi mynd af þróun íslenskrar listasögu né verið greinargóð úttekt á tilteknu skeiði þess. Þegar öllu er á botninn hvolft er það smekkur eins manns sem liggur til grundvallar. Sýningarstjóranum vill það til happs að sá maður var Ragnar Jónsson í Smára og sýningunni tekst þar af leiðandi að gera þróun íslenskrar myndlistar skil að einhverju leyti.

Sýningin er athyglisverðari en aðrar áþekkar sýningar einmitt fyrir þær sakir að þetta eru einvörðungu verk úr stofngjöf Ragnars. Mörg verka sýningarinnar eru áhugafólki um myndlist að góðu kunn, en þó líklega flest úr bókum. Sum verkin hafa meira að segja öðlast allt að því rokkstjörnufrægð, besta dæmið um það er Fjallamjólk Kjarvals. Enn önnur verk verðskulda að vera þekktari en raun ber vitni. Ragnar lagði þung lóð á vogarskálarnar í listkynningu með því að færa alþýðufólki sum þessara verka, sem og önnur þekkt íslensk málverk, í formi endurprentana. Það er þó tvennt ólíkt að standa frammi fyrir endurprentun af málverki og málverkinu sjálfu. Það er því fagnaðarefni að sýning sem þessi hafi verið sett upp, sýning sem gefur áhugasömum innlit í merkilega gjöf Ragnars Jónssonar í Smára til íslenskrar alþýðu.

Grétar Þór Sigurðsson

Sýningin stendur til 15. september, en Listasafn Árnesinga er opið alla daga frá 12 til 18. Þess ber að geta að ekkert kostar inn á safnið.

Dieter K. Müller giving a speech on the second day of the Arctic Art Summit. Photo credit: Kaisa-Reetta Seppänen.

Dieter K. Müller giving a speech on the second day of the Arctic Art Summit. Photo credit: Kaisa-Reetta Seppänen. Panel discussion Sustainability through Art and Culture in the Arctic. From left to right: Tuuli Ojala, Jan Borm, Gunvor Guttorm, Daniel Chartier. Photo credit: Janne Jakola.

Panel discussion Sustainability through Art and Culture in the Arctic. From left to right: Tuuli Ojala, Jan Borm, Gunvor Guttorm, Daniel Chartier. Photo credit: Janne Jakola. Panel discussion Decolonizing Research Practices. Speakers: Krista Ulujuk Zawadski, Charissa von Harringa, Pia Lindman . Moderator: Heather Igloliorte. Photo credit: Kaisa-Reetta Seppänen.

Panel discussion Decolonizing Research Practices. Speakers: Krista Ulujuk Zawadski, Charissa von Harringa, Pia Lindman . Moderator: Heather Igloliorte. Photo credit: Kaisa-Reetta Seppänen. Panel discussion Duodji in Contemporary Context. From left to right: Irene Snarby, Duojár Katarina Spiik Skum, Svein Aamold, Gunvor Guttorm, Anniina Turunen. Photo credit: Janne Jakola.

Panel discussion Duodji in Contemporary Context. From left to right: Irene Snarby, Duojár Katarina Spiik Skum, Svein Aamold, Gunvor Guttorm, Anniina Turunen. Photo credit: Janne Jakola.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery. Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery. Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.

Installation view Fingered Eyed at i8 Gallery.