Isle of Art: an interview with the author Sarah Schug

Isle of Art: an interview with the author Sarah Schug

Sarah Schug is a German journalist based in Brussels who has been traveling in Iceland since 2009, after noticing the lack of books about Icelandic art she decided to take action and fill the gap. Her recently published book Isle of Art constitutes a comprehensive manual for those who want to get an insight of what is going on in the island’s art scene.

Sarah, when did you come in contact with Iceland for the first time? When and why did you decide to write a whole book about its art scene?

The first time I came in contact with Iceland was at the age of 7, when the TV series Nonni & Manni was broadcasted in Germany, and I fell in love with the horses and turf houses and waterfalls. It is since then that I wanted to see Iceland, and I did so for the first time in 2009, if I remember correctly. I totally fell in love with it again, and returned several times. As I’ve been working as an art and culture journalist, and Icelandic artists started popping up in exhibitions in Belgium, where I live, I started to put the two together and wanted to find out more about it. I actually searched for books about the subject, and couldn’t find much, except for monographs. I really felt like there was a gap to be filled. When I told my friend Pauline Miko, a Belgian-Hungarian photographer about the idea and she said she’d do the photos, I decided to just go for it.

Can you tell me something about the process of researching, selecting and interviewing artists and the people of the Icelandic art community?

First there was a lot of reading and desk research, and then I went to live in Reykjavík with my boyfriend for two months, from February to April 2017. I remember, the day we arrived, we directly went to an opening at i8 gallery. During these two months I attended lots of openings and exhibitions, visited art spaces and galleries, and talked with so many people from the Icelandic art world, getting to know the scene from the inside. The lack of existing literature on the subject meant that word of mouth was the principal source of information. In the end you quickly get a grasp for what’s important, which names come up again and again, and so on. Regarding the selection: I spoke to newbies and old timers, Icelanders and foreigners, young and old artists, students and stars. The idea wasn’t to show “the best” artists (whatever that even means), but to paint a full picture of the art scene as a whole by bringing together a rich canon of different voices and perspectives from inside the Icelandic art community.

From left: artists Sara Riel and Ragnar Kjartansson, collector Pétur Arason.

From left: artists Sara Riel and Ragnar Kjartansson, collector Pétur Arason.

What makes the Icelandic art scene interesting in your opinion?

I think it’s a really intriguing and unique case to examine, not only because of its remote geographic location, but also due to its short history. And of course it’s incredible how vibrant and active it is, how many great artists it has brought about, despite having such a small population. It has all the ingredients necessary for a vibrant scene: commercial galleries, museums, art schools and a multitude of independent art spaces. At the same time, it’s still somehow positioned on the sidelines of the international art market, which is interesting as well.

How does the Icelandic art scene differ from the one you experience everyday in Brussels?

I think there is a spirit of creative freedom, playfulness, collaboration and fearless experimentation that you hardly find anywhere else. Of course there is also no doubt that globalization, digitalization, and the explosion of international travel have caused the island’s art scene to become bigger, more professional, and more diverse. But I found it very pleasant how accessible and welcoming it was, which facilitated the creation of this book extremely. In places like London or Paris, which have very closed-off art scenes, the process would have been very different and more difficult. In Iceland, everyone is just a phone call away; everybody knows each other. News travel fast, and when we arrived up north, we were stunned to find out that people had already been tipped off about us. In that sense, it’s not too different from Brussels or Belgium, whose art scene is also quite open and accessible – I think it’s typical for smaller countries.

The biggest difference is probably the existence or development of an art market and a collector base. Belgium has one of the highest collector densities in the world together with Switzerland, and in Iceland there are maybe five serious collectors. Belgium has a massive number of commercial galleries, Iceland has three. There are no art fairs in Iceland like Art Brussels. It’s a completely different situation. But this positioning slightly on the sidelines of the art market also has its advantages: a certain creative freedom and fearlessness and confidence come with it, which a lot of artists actually mentioned in their interviews.

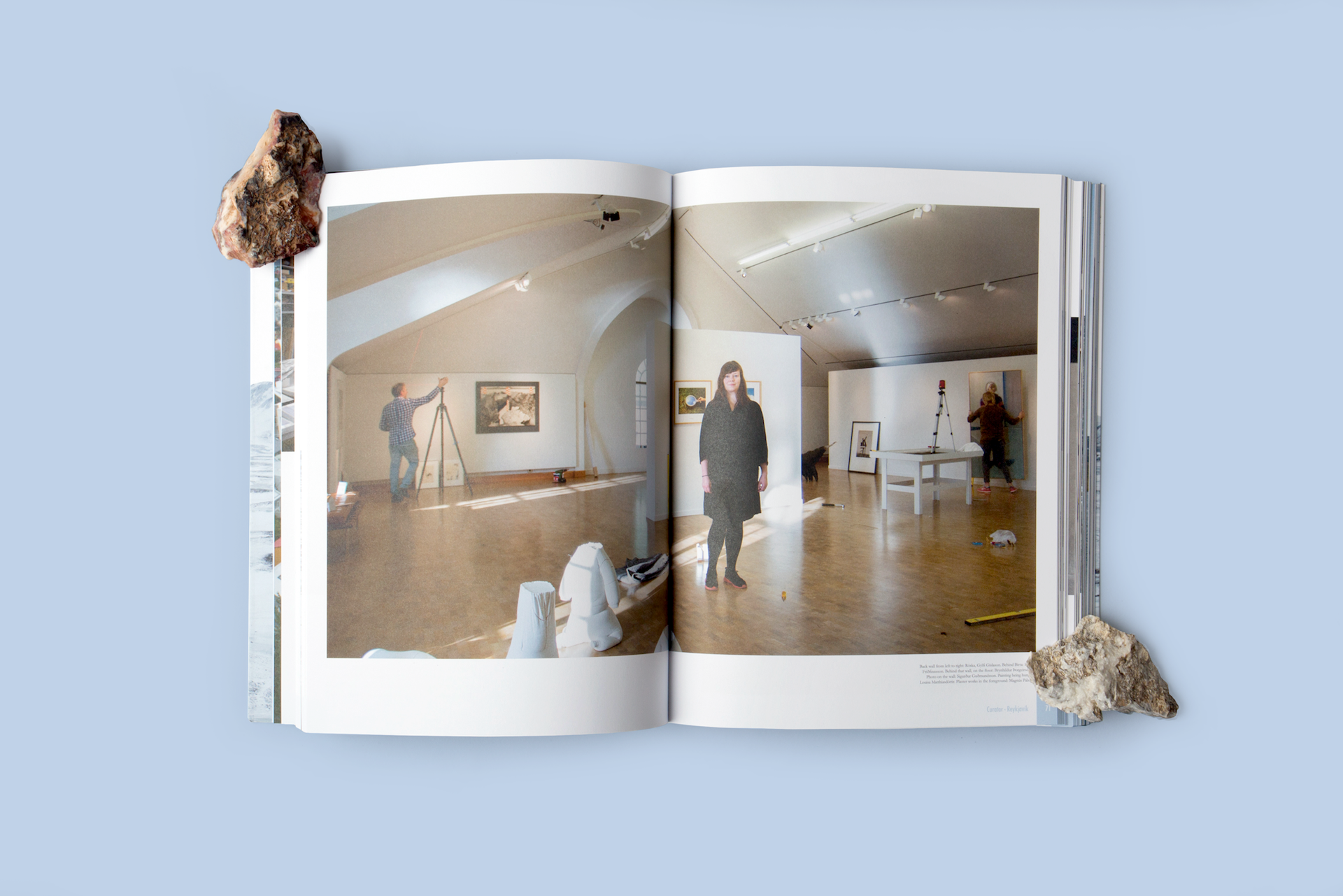

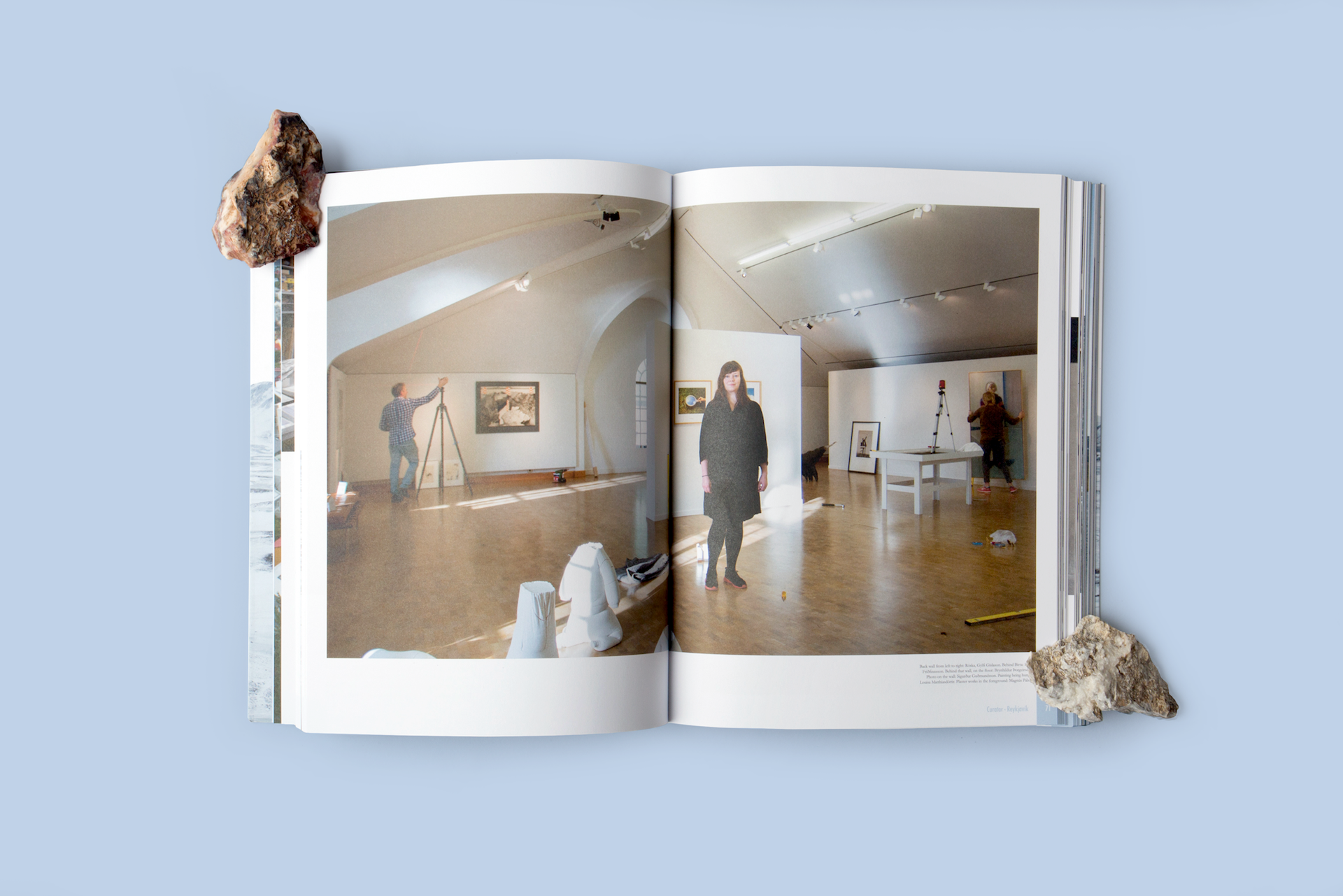

Installation view: Slæmur Félagsskapur / Bad Company, at Kling og Bang, March – April, 2017.

Installation view: Slæmur Félagsskapur / Bad Company, at Kling og Bang, March – April, 2017.

How do you see the future of the Icelandic art scene?

I think it’s in the process of growing up. Just take the opening of the Marshall House, which happened while I was living in Reykjavík actually. I was lucky to witness this pivotal moment first-hand. Many artists I talked to described it as a game-changing, and I think it has the potential to be a new destination on the international art map. At the same time, many voiced concerns about the grassroots scene. With Nýlo and Kling & Bang in the fancy Marshall House – who will fill that gap? And how will the grassroots scene be strong when there’s a housing crisis going on and space has become unaffordable? But normally art always finds its way – I think we will see more initiatives outside of the city center, and places such as RÝMD or Midpunkt are signs for that. And I think there will be more and more art spaces in the countryside and outside of Reykjavík, a movement which has already begun as well. I was amazed by the high-quality exhibitions I found in small villages such as Hjalteyri or Djúpivogur.

The book is already sold out in Iceland, this constitutes a really good feedback. What do you feel the book has accomplished? And is there something you regret you didn’t manage to include in Isle of Art?

I feel, and that’s the feedback I have been getting by a lot of people from the Icelandic art scene, that the book is a kind of time capsule, showing the Icelandic art scene in its full splendor at this certain point in time, while also looking back on its past and trying to have a look at its future as well. I think the book is valuable to everyone who wants to learn more about what’s going on in Iceland when it comes to art, but it can be also an interesting basis for discussions within the Icelandic art scene itself.

I don’t have any regrets, but of course there are many artists whom I love and respect that are not in the book, because you just can’t include everyone. The more pages you print, the more expensive it gets, and as it is self-financed, we couldn’t afford more pages, 256 is already quite a lot, I think! I would love to do a second book at one point with all the artists I haven’t been able to give pages in this one – so, if someone wants to sponsor or fund it, I’m all ears.

Sigurður Guðmundsson, Eggin í Gleðivík, Djúpivogur, 2009.

Sigurður Guðmundsson, Eggin í Gleðivík, Djúpivogur, 2009.

The book will launch at the Living Art Museum on the 28th of May, right? Would you like to tell us something about the event?

Yes, exactly. When the first books arrived in Iceland a lot of people were asking about a launch event and so I decided to organize one. I wanted it to be at a space that is part of the book, and The Living Art Museum has had such significance for Iceland’s art scene that I am very happy to be able to do it there. I’m also super happy about all the support I’m getting: Icelandair offered to ship more books from Belgium, and Reykjavik Roasters are providing coffee. The idea is to create a kind of informal „round table“, an art café if you will, and everyone is invited to stay and chat about the state of the Icelandic art scene (which is something I realised Icelandic artist love to do). One wall will be covered with posters displaying decisive quotes by artists, gallerists, curators, etc. taken from the book, as an entry point and food for thought. The whole idea is not only a nod to Guðmundur Jónsson’s Listamenn, whose frame shop serves as a bit of the living room or of the art scene where everyone hangs out and chats and drinks coffee, but also to the research process of the book, which largely consisted of conversations over coffee.

Is there something else you would like to say before we end the interview?

Just a big thank you to everyone – I’m amazed how warmly I’ve been welcomed by everyone, and how helpful people are, especially the artists themselves. Takk fyrir!

Ana Victoria Bruno

Sarah Schug (1980) is a Brussels-based German journalist who writes about art, culture, design and photography. Her work has been published in The Word Magazine, The Bulletin, H.O.M.E. Magazine, Previiew Journal, Crust Magazine, Tique Art Paper, and others. In 2014 she launched independent online magazine See you there, putting forward Belgium’s cultural scene, and curated the exhibition “No place like home” at Brussels Art Department.

Isle of Art website: https://www.isleofartbook.com

Photo Credit: Pauline Mikó. Ragnar Kjartansson’s portrait: Lilja Birgisdóttir.

The book will launch on Tuesday the 28th at 18:00 at Nýlistasafnið / The Living Art Museum.

Still Images from the installation: Dieter Roth, Seyðisfjörður Slides – Every View of a Town 1988-1995, 1995

Still Images from the installation: Dieter Roth, Seyðisfjörður Slides – Every View of a Town 1988-1995, 1995 Installation view of the exhibition Collectors at Skaftfell – Center for Visual Art.

Installation view of the exhibition Collectors at Skaftfell – Center for Visual Art.