About science, emotions and the Roman Empire: a conversation with Geirþrúður Finnbogadóttir Hjörvar

About science, emotions and the Roman Empire: a conversation with Geirþrúður Finnbogadóttir Hjörvar

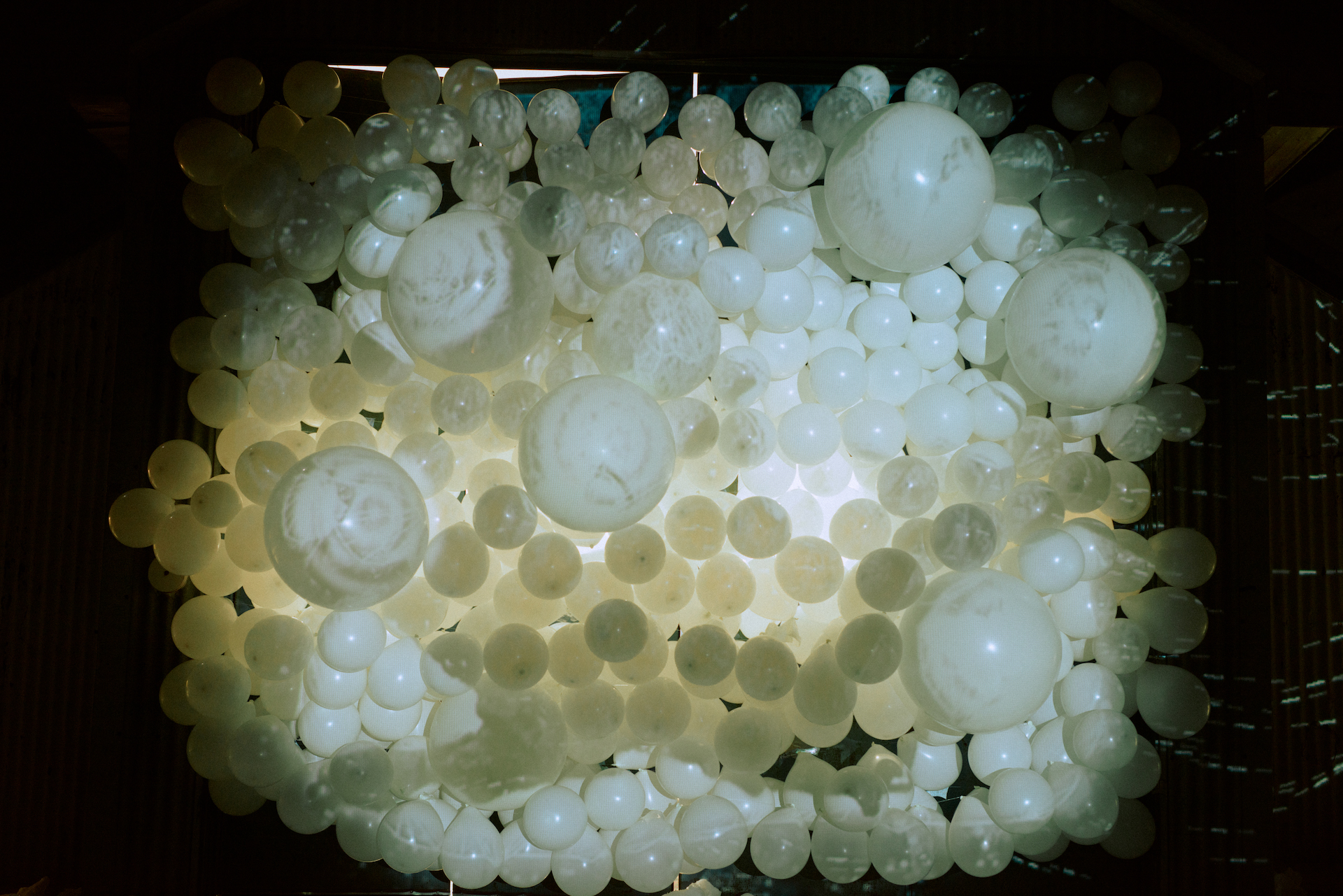

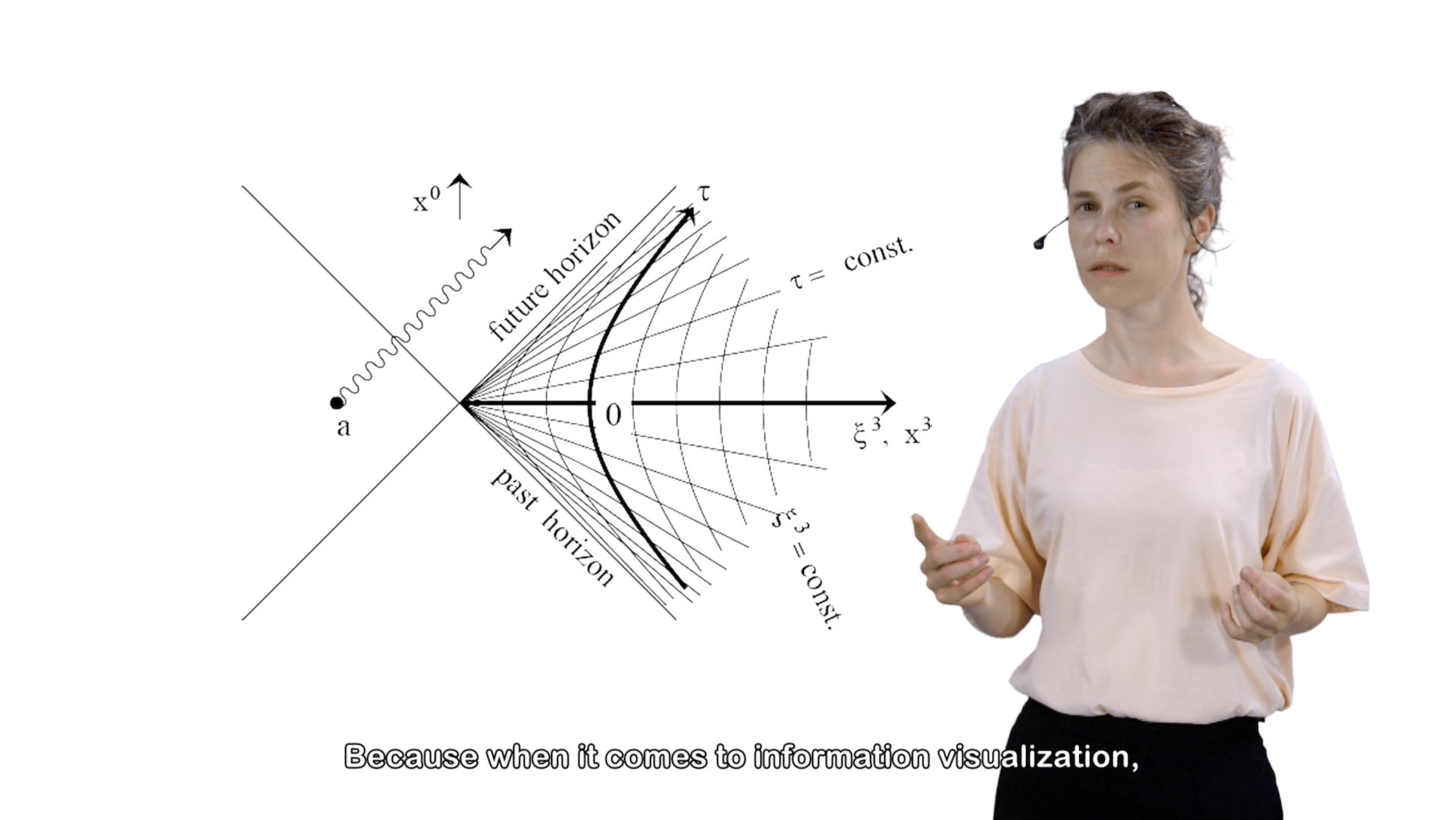

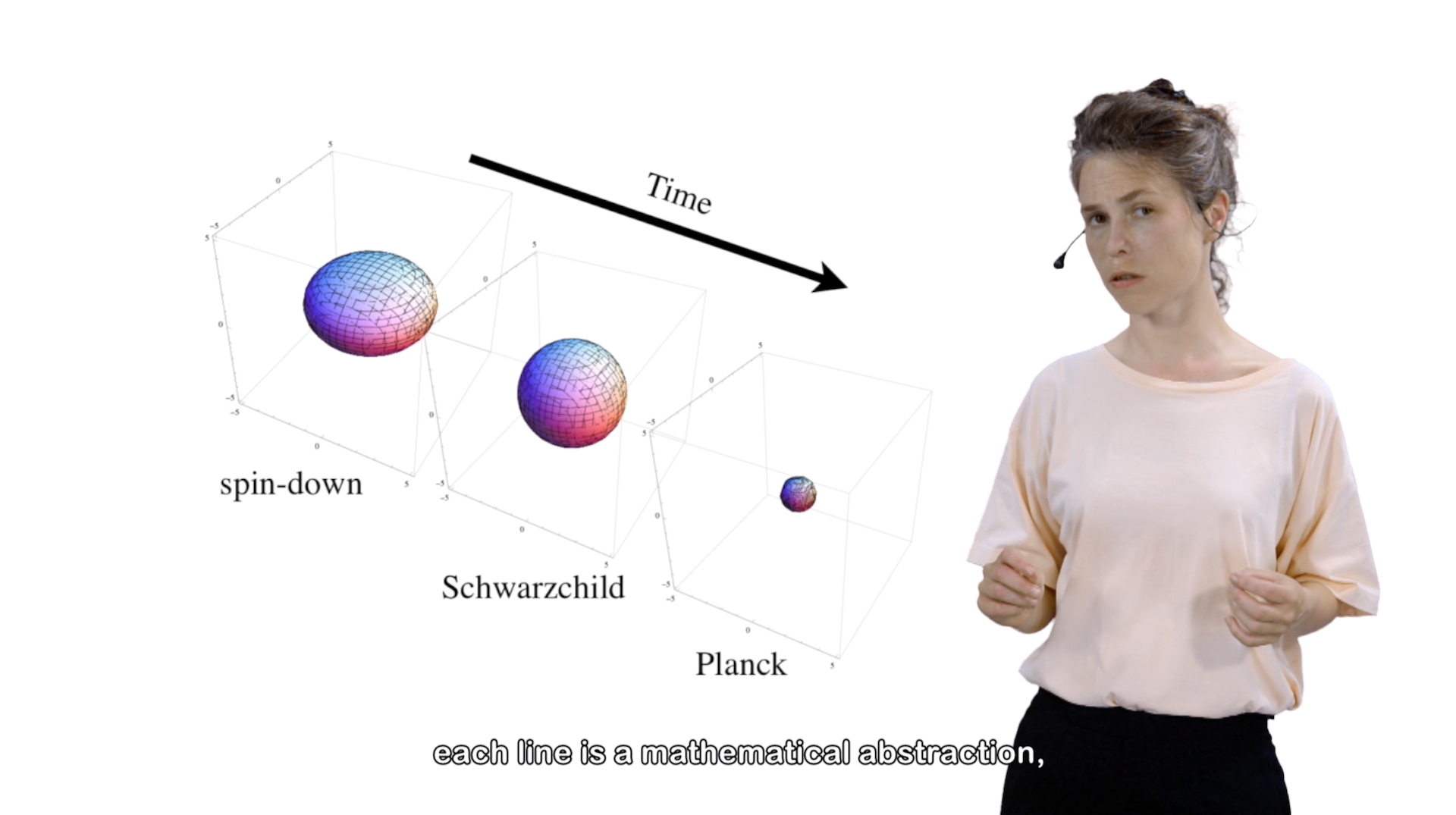

A few weeks ago I had a chat with Geirþrúður Finnbogadóttir Hjörvar about her show Desargues’s Theorem Lecture and Three Other Sculptures at Kling og Bang. Some sculptures would welcome the visitors into the exhibition, playing on the concepts of two-dimensional and three-dimensional, real and unreal, questioning what existence means. The video work Desargues’s Theorem Lecture would then give an insight on the process the artist went through, a sort of key to read the sculptures. Geirþrúður’s mind seems to be an unresting machine which absorbs, processes and reformulates realities in an extremely mathematical and logical way. Through this conversation I tried to grasp her creative process and her understanding of art.

I would like to start this conversation by asking you to explain a little bit further the first sentence of the text in your show’s pamphlet “Desargues’s Theorem Lecture is a video that relies on the assumption that ideas have shapes.”, I find the concept of art dwelling in space between ideas and the physical world really interesting. Where does this idea come from?

At that time, and still maybe now, I was thinking about the relationship between science and alchemy, since alchemy has as forefather a scientific thought, even though this connection is really suppressed. They have a common impulse to do analytical things and to get into a state of mind which contemplates the possibility of figuring things out. I wanted to see what I could do with that, there is a kind of mysticism inherit in all sort of sciences and it is interesting to see how and if they can be brought together in a way that is useful. Everyone who goes into art or who appreciates art is aware that there is some kind of underlying relationship between forms and a more abstract sense, feelings and thoughts. It‘s a bit hard to trace where this idea came from, but at the basis of this work there is a very sincere impulse.

What do you mean by “useful”?

Well, useful as it is not about making fun of science or to try to disqualify it. Science and mysticism are intertwined and you can‘t really go further in either direction without accepting both. On one hand science is a very enclosed system, it would support itself, but on the other hand if you want to get all mystic you will probably end up joining your cult and then whatever you say becomes so enclosed that even talking to other people doesn‘t make any sense anymore. But between these two systems there is something really interesting.

I am also thinking about quantum physics which explores how something thought impossible could actually exist in other quantum realities.

Yes exactly, the further science goes the further it goes back to incredibly metaphysical understandings and statements about how nothing is real after all. And I think if you are serious and eager to discover, then you are following the same track someone in the 15th century would be following when they were making gold, which is also an allegory for knowledge. But it feels like, especially in a social sense, science is used to scare you away from wanting to know something, they say you have to know the scientific method and you probably need ten years of studies to be qualified for it. So this playfulness is not really allowed.

Your work is also quite ironic, right?

It is actually weirdly not ironic. It seems ironic because it is really sincere. The impulse is to create some kind of a narrative, a sort of suspended belief, and to see science as a narrative. If it seems ironic it is because I wanted to do that, since I‘m very ironic.

In the text you talk about the work in terms of a coded love letter, how did you weave together science and emotion?

In a way that is what I am saying in terms of that it is completely sincere, I did go through all this process that I described in the video. At a certain point I was a bit addicted at looking at all these images of certain things so I just did it more and more, and there is a point in which you exhaust certain materials visually on google and then you start to have a real eye for what brings you into a new place. I think there was something going on in that theory that I just found interesting to explore and then I just kept thinking about that and I really started making this model. On one hand it was a little bit of a joke, the theorem is completely abstract and I was making a thing out of something completely immaterial, I was completely aware that it is kind of funny to try to do that, also because I used whatever was in the kitchen. It was really playful, and I think that was also part of it, this will to take something really scientific and doing something so playful with it, so irrelevant about it. But it was part of something a little bit more concrete, I wanted to make a sculpture out of the theorem, and why did I want to do something which doesn‘t make sense? Well, in part because it didn‘t make sense, if it did make sense then it would have been so pointless. I think the reason why anyone has a passion for something remains inexplicable, and I suppose the only way to grasp it is to make this analogy with things that are part of an emotional landscape. The scientific world says that we have to separate science and emotions, but I don‘t agree with that, I think things going on in the mind can be very passionate in a very abstract way and I think passions can be extremely rational.

There is also a kind of instinctive side to discovering how things work.

Well, you know, the mind is the biggest sexual organ, they say. We use all kind of ways to seduce who or whatever we are interested in. In the background of my mind I was also thinking about the implicit masculine nature of scientific discourse, which is very much ego-based and willing to dominate, the scientist is this alpha male who seduces with his great brain. To me it was interesting to see what it feels like to take on that position.

And how did you feel in this alpha man/scientist role?

It was fun, I’m still trying to have a dialogue with that scientific part of myself, I think it is something that everyone should do. It is conditioning for a woman to think about science as a complicated thing. Wanting to shy away from technology is really common, as it is scary, but it is important to be able to take something scientific and make it yours, play with it, you don’t have to be afraid of not being qualified. And this is also part of this desire of creating this scientific discourse and being convincing, because it is just a theory.

Talking about being convincing, you state in the show’s pamphlet that the piece is very much inspired by the 20th century communication, I think the format you have decided to use for this video is really interesting. In which terms are you interested in the 20th century communication?

I think it is about being contemporary, the modern communication defines the era on every level. Concretely, it represents also an interest in science in terms of knowledge and how it is communicated. I never stop being amazed by how easy it is to have information nowadays compared to how it was before, I managed to master four different programs thanks to Youtube tutorials. I think the piece is a kind of celebration of that, I find interesting the relationship between the word and the images that we have become able to recognize, and this is completely new. It is part of mass culture: now everyone knows how to get a picture from google and put it in a powerpoint, and that produces this logic which is part of our consciousness now. On the other side, I’m interested in the narratives in these kind of media which are really competitive so within a certain amount of time you have to gain the viewer’s attention. But also, considering the social-political climate, these media are quite dangerous, the flat earth theory is the perfect example of how we just apparently got back to the middle age all thanks to precisely this kind of presentations of information. Sometimes I can just watch these videos and sincerely be a little bit scared, because I can feel critical about them, since I’m visually trained to be able to understand all these subtleties, but I wonder if all of the millions viewers who have seen the video are also trained or maybe they just believe it for what it appears. I think there is something about artistic education which is quite valuable in terms of decoding presentations of information, and it actually would be useful for people to navigate those media.

Talking about the importance of art history, I was browsing your website I noticed that there are recurring symbols of the Roman Empire, architectural elements like the Ara Pacis and the columns in Desargues’ Theorem Lecture.

I’m really fascinated by the Roman Empire because you could decode or you could foresee a lot of things about history’s unfolding by learning Roman history. You can actually understand today so much better by understanding Rome than by understanding any contemporary theory. I have also being concretely influenced by the financial crash in Iceland, I was in Europe at the time and it was a very strange sensation because at that point no one in the rest of Europe could perceive a social movement as being anything other than populist and I had really mixed feelings whilst I felt there was such a huge possibility to create something, but then again there are so many things that can go wrong if there is not an understanding of historical perspectives underlying mass movements. On one hand there is a lack of class-conscious reading of history in the general education, on the other hand those training to be part of the upper classes universally receive a classicist education which provides them with a playbook to maintain power, they just don’t have to come up with a new strategy if they know the history, it is all there, like a toolbox for countering the next move.

Your book Mindgames, published in 2012, brings together John Lennon, Henri Lefebvre, Halldor Laxness and Caligula, it looks like you are taking fragments from different areas of knowledge and mixing them together. What was your aim? And why did you choose these four subjects?

The idea was that they represent different spheres in society, it was a sort of mathematical formula which brings together the politician, the musician, the theorist and the writer, I was fascinated by this relationship they had with recognition and with their audience. It is a lot about time, repetitions and patterns. I was thinking in a cybernetic kind of way when there is a feedback and when there isn’t and how the author transmits information to the reader and that this would produce something new, a feedback which then will influence the author. These are all kind of subsystems, and I suppose I was trying to figure out my position and wondering what the contemporary artist could hope to achieve by creating new work, if artists can really influence anyone at any level, if that’s actually the aim, and how quality is created.

And did you find an answer to these questions?

Yeah, in my own kind of mathematical way, in terms of theory, I found the mathematical kind of calculations to figure out the probability, the correct proportion between the different elements you need to communicate something. I probably figured out for myself what I wanted and how I wanted to make art.

My last question does not really relate to your own work, but since you have been living abroad for about ten years, in Holland, Germany and Colombia and you had the chance to experience different art scenes, I would like to ask you what you think about the Icelandic contemporary art scene.

I think it is pretty good, you can actually see some pretty good works and shows. There are a lot of big cities where a lot of things are happening and you really have to try hard to find good exhibitions, while in Iceland the art scene is at a surprisingly good level considering its size. I think there are a lot of artists doing super interesting things. If I wanted to make a critique it would be that in the past there has been a quite strong impulse to try to suppress any kind of intellectual sensibility. But this is changing though, there is more space now, because it’s just a matter of having a wider spectrum, and I think it’s also quite valuable that there is a lot of room for people who are not into this super intellectual/critical/reading kind of discourse, while in a lot of places, for instance in Europe, you have to make sure you’ve read certain books and check out certain things to be allowed to this sphere, and that art under those conditions can be boring because that doesn’t come from an inner desire of the artists. So I think it is nice that here there is that side of the spectrum, but I think it’s also good that you can include in something more intellectual or conceptual and to try not to dismiss that, and I think that’s becoming more accepted than it was before.

Ana Victoria Bruno

Photo credits:

Stills from the video: courtesy of the artist.

Photos of the sculptures: Vigfús Birgisson.

Website of the artist: http://www.geirthrudur.com