Photography and Geologic Time – an inquiry into the perception of time

Normally, we think of rocks as dead material, but on a microscopic level they are in constant growth, animated by invisible chemical processes. The formation of lava rocks is namely an active process from the outset that continues to develop throughout their life cycle. The project revolves around how one can expand the perception of time by looking at the internal structures and processes of lava rocks. (Veronika Geiger)

Detail of Hraun (2016)

Detail of Hraun (2016)

Geology and photography are seemingly two fields of thought and action running in parallel streams that rarely intersect with the other except when photographs are taken to rely scientific information about geologic structures. However, both have the ability to relay contemplative inquiry into the perception of time through simple data. Both photography and geology hold a return to origins, a seeking out of the bedrock from which we can know what we know. They both relay a simple equation of cause and effect, whether in the darkroom or through larger processes like the shifting of tectonic plates. Veronika Geiger’s approach to these two fields is inspired by Land Art practices and in this way photography becomes an extension of Land Art. With a background in Fine Art photography from Glasgow School of Art and a recent MFA from Iceland Academy of the Arts, Veronika delves into her experiments with the compulsion of a hypothesis being tested. Methodologically she follows her curiosity with the balance of imagination and chemical fact, reality and speculation.

Hraun (2016) No. 6281 and 6285, Gelatin silver print, 100 x 150 cm, Rock type: Gabbro xenoliths from silicic tuff, Place: Kambsfjall, Króksfjördur, Vestfirdir, Iceland, Age: 10 million years old, Petrographic slides borrowed from the Icelandic Institute of Natural History

Hraun (2016) No. 6281 and 6285, Gelatin silver print, 100 x 150 cm, Rock type: Gabbro xenoliths from silicic tuff, Place: Kambsfjall, Króksfjördur, Vestfirdir, Iceland, Age: 10 million years old, Petrographic slides borrowed from the Icelandic Institute of Natural History

For five days at the beginning of August 2016, Veronika and I followed a group of geologists with a variety of research focuses in the Askja area and especially in the new lavafield, Holuhraun. Holuhraun lies just north of Vatnajökull in the Highlands. On August 29, 2014, a volcanic eruption began that produced lava spreading over 85 square km by the time the eruption ended on February 27, 2015. The original surface of Holuhraun was an older lava flow from 1797 (Icelandic Meteorological Office.)

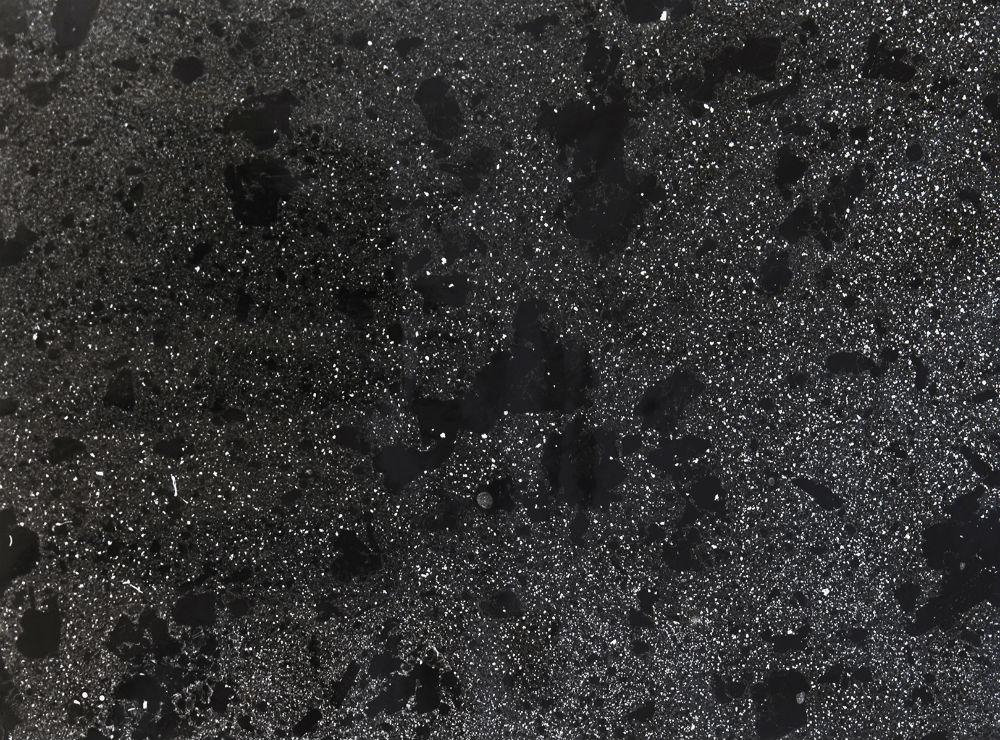

Holuhraun lava field

Holuhraun lava field

With the expertise of Morten Riishus, a danish senior researcher in volcanology and geology at the Institute of Earth Science, University of Iceland, we got the priviledge to get insights into geological research methods in the field. Three overlapping research projects took place; the first was looking at the geomorphological and geochemical processes of change in relation to how volcanic glass, dust, and sand from Vatnajökull is transported towards the Northeast across the dunes in the desert landscape north of the glacier; another project looked at the microbiology and colonization of barren land at Holuhraun, i.e. the first signs of life on new lava; the third project aimed to create an analog of the Mars Curiousity Rover’s gigapanning scheme, a camera that creates a matrix of images with the ability to be zoomed in up to 800 times. We were grateful to be allowed this chance to follow the geologists’ work in the field, asking them questions and documenting their process.

Geologist Morten Riishuus and microbiologist Anu Hynninen at work

Geologist Morten Riishuus and microbiologist Anu Hynninen at work

One day we rode with the geologists through a valley that is flooded daily with glacial runoff. These glacial rivulets arrive in tiny trickles from a great distance. With light sensitive paper placed gingerly in the path of the rivulets, Veronika captured an aspect of their movement and aesthetic that a normal photograph couldn’t capture. Her ‘photograph’ of the glacial flood rivulets were from the actual body of the rivulets, their weight and flow appearing on the paper in different shades. The paper has received its color and patterning directly from the water, with immediate impressions of the light and weather-conditions present on the day they were made.

Geologic tool

Geologic tool

Another day we trekked with sheets of handmade paper to Viti, a crater filled with warm cloudy blue water situated next to the larger crater lake, Öskjuvatn. The plain of black sand that we crossed before arriving at the crater gave us a good sense of the surrounding landscape and its vastness. Taking the papers one at a time, some more porous and thick than others, they were let into the silty, mud bottom of Viti’s edges where they gathered directly onto the paper an impression of how sediments are transported. In an expansion of the photographic moment, an impression was taken that included movement, weight, and porosity.

Víti Crater

Víti Crater

Later that day we followed the geologists to an area where natural springs created a flowing creek among new lava and old lava. Here, algae that had grown in the spring was placed onto the light sensitive paper and set directly in the sun. Again, the weight and body of the algae created an impression on the paper. In places where the algae blocked the sunlight, the paper remained a distinct shade from the parts marked by sunlight. Any chemical variations resulting from reactions between the water, the algae, and the paper will be seen later in the laboratory.

Hiking on a trail marked through the edge of Holohraun, the two year old lava was distinctly loud under our boots, the brittle whisps of once fluid mass strung across larger bodies of lavarock. In some areas, deposits of sulphur, white and yellow, formed along the mouths of cavernous openings. Attempts were made to take impressions on these deposits, as well as on the sun-heated surfaces. Taking samples of these, as well as of the fine lunar-like sand, Veronika hopes to find a chemical means of fixing them to the image.

Later in Reykjavík, we recorded an open conversation between Morten, Veronika, and I, each representing the approaches of geology, photography, and art history/theory. The intention was to learn more about each of our research interests, the craft of each of our fields, and how they overlapped. It offered me the opportunity to reflect on the idea of the geologic time period of the Anthropocene as an aesthetic event. The Anthropocene opens up an epochal way of thinking about time as well as narrative. The narrative involved in threading the events of an epoch shows how we create meaning in the space between the encounter of different temporalities. This is the encounter that is crucial in Geiger’s project. An example of an encounter in geologic time-scales is presented by Morten Riishuus in the following excerpt from the interview:

As you’re driving from Akureyri east, you’re driving through a volcanic succession that is tilted, layered and packaged toward the Southeast…. If you think about it, you’re driving east and the landscape you’re driving through, this tilted strata towards the East, means you’re driving forward in time as all the layers disappear into the earth. (Morten Riishuus)

Lava from Holuhraun eruption

Lava from Holuhraun eruption

The media theorist, Jussi Parikka writes about the term deep time which was first used by Siefried Zielinski in the discussion of aspects of media. Parikka’s new materialism of media emphasies a different notion of temporality and spatiality by pointing out how media technology is tightly linked with natural materials. Expanding the temporal use of the term deep time, Parikka uses it to combine the geological materials enabling media processes, and the temporality of the earth, which consists of billions of years of build-up and break-down.

In this way, Veronika’s experiments with photography continue the narrative of material processes of the earth out-of-ground, cultivating the temporality of the earth in a new medium that includes the human senses. In her project at Holuhraun she continued her focus on how one can expand the perception of time by looking at the internal structures and processes of lava rocks. By observing the physical layers and traces of time in the rock, the tension between the geological time-scale and biological time-scale becomes concrete.

Erin Honeycutt

Here is a link to a transcription of the interview in its entirety: interview-transcription