The Permanent Recycling of Eternal Recurrence

The Permanent Recycling of Eternal Recurrence

Alicja Kwade’s exhibition, ‘A Trillionth of a Second,’ is on display at i8 Gallery from June 22nd to August 12th, 2017.

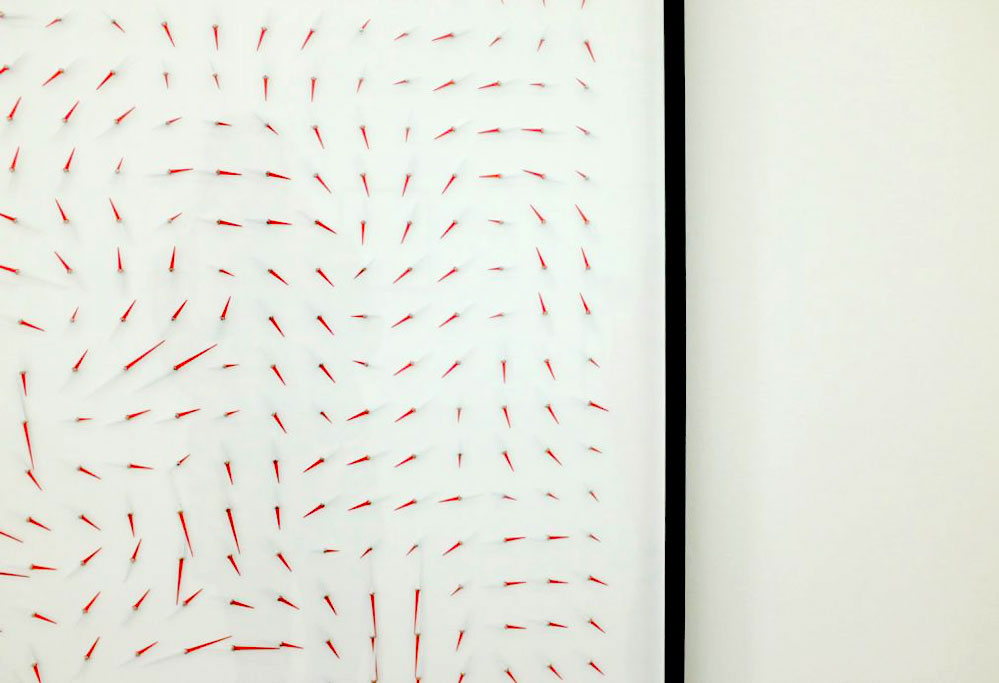

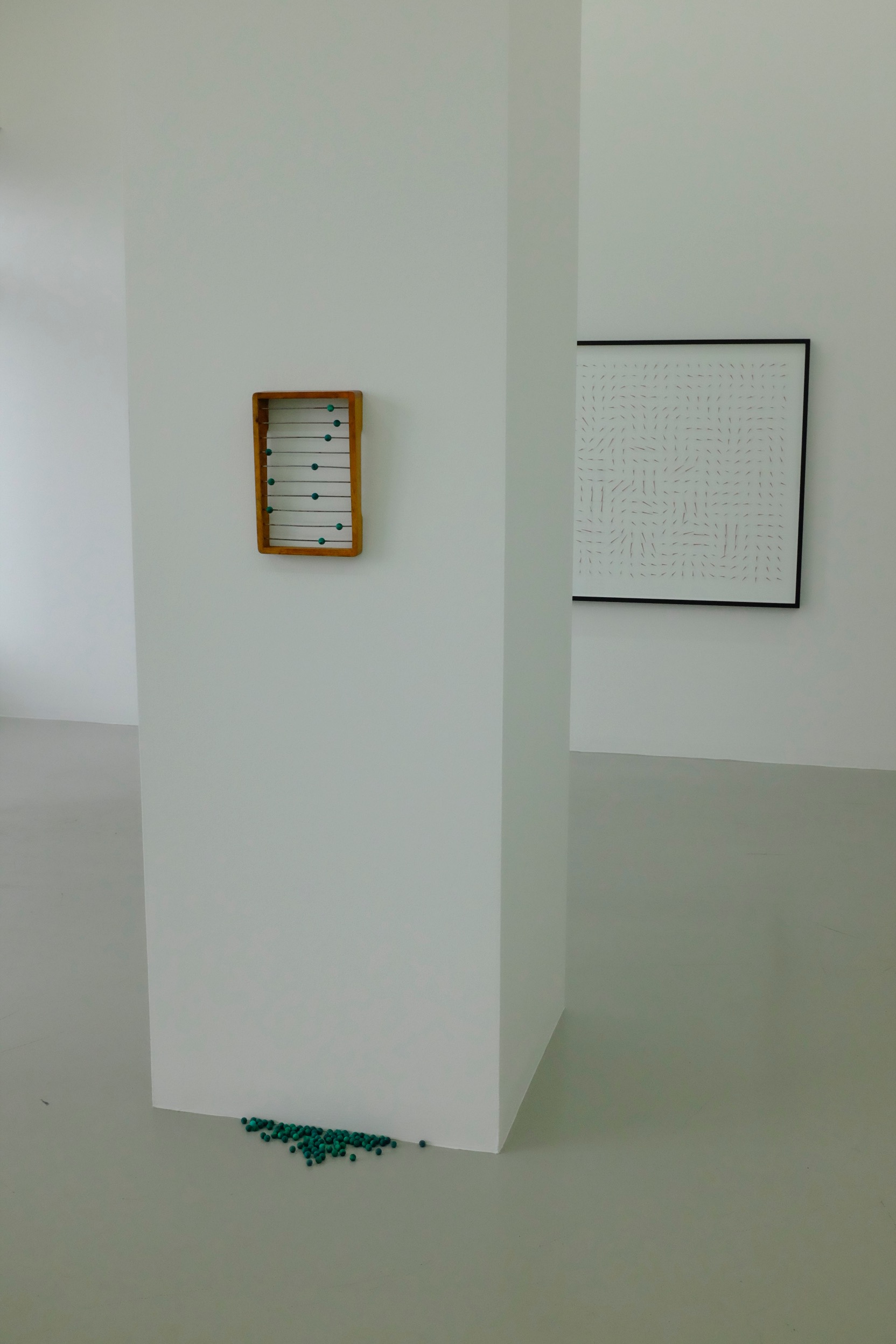

In glass cases sit what appears to be vase-like structures of an undeterminable age, while the titles of the works suggest wholly different objects altogether. The vase titled Lampe, for example, is composed of ground lamp, epoxy resin, glass, and brass, likewise with Kaminuhr (Table Clock), Computer (PowerMac), and iPhone. Compass needles in A trillionth of a second (I) and clock arms in Ein Monat (November 2017) form wave compositions in flat wall pieces, while a third wall piece in the form of a found abacus, Linienland III, reminds the viewer of the basics. The wall pieces seemingly ground the material processes that have occurred within the objects in glass cases with their structured systems of measurement.

Alicja Kwade asks big questions about how language shapes perception and what the consequences are for visual proof of the existence of gravitational waves. I spoke with the artist in a winding conversation to try to get a better understanding of her inspiration and process.

Erin: When I first looked at your exhibition, I was reminded of the show in Vienna from a few years ago, ‘Rare Earth’ at Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21). The curators were exploring this idea that our technology is continuing geological processes happening inside the earth’s layers on the outside surface.

Alicja: Yeah, I missed the show but it would be very interesting for me. It’s actually what I play with because you have this geological layer that is used to place things in time. It’s not just time but it’s how we figure out about time, what it is, and where these measurements come from. In this case, it’s coming from all these elements and measurements of elements, which are in this planet, somewhat like a… bowl of elements.

So that is a good starting point to think about my work. But for me, is not just about time. I think people sometimes simplify my work a little and just think of this poetic use of time because it is understandable for everybody. For me, time is just one template, one thing we invented to create reality. I try more to question all facts of reality- what that could be, what it is, where it comes from, what language is also doing to that, what we name things. We feel things or experience things because we have names for them. I try to see all these facets about matter, and with matter, what reality is, and what we are to that, and what we are to matter as well.

Erin: And how our perception is really what shapes that…

Alicja: Yes, our perception is really very much ‘man is the center of the universe,’ but it is that way because we can’t do differently since we are the only recipients of our world. So even if we, with all the technology and knowledge, think we know more and more, it’s still from our point of view and therefore still very little.

Erin: Because all we know about the world comes from our senses or the extensions we make of them through instruments…

Alicja: Yes, and they are kind of primitive. Of course, we are able to over-jump our senses in a certain way because that’s the tragedy and the great thing about human beings, I think. But on the other hand, it’s still very limited. So it is still our imagination and our perception of our reality that is just based on us which is quite a simple thing and everybody knows that. However, to just question it with simple facts in daily life is quite interesting because we forget about that. We probably even question the biggest things but we forget that the table is probably not a table but a piece of wood- so it’s a tree, and the tree is a bunch of atoms and those atoms are coming from the universe, and so you know… All these layers.

Erin: It is so beautiful just to think in this way. It has a bit of this vanitas theme to it, like a still life, in a way.

Alicja: Yeah, that helps, but also they’re just objects. Vanitas is just a term, but of course, I crush these things to dust and I recreate other things and they are forms of time made of other forms. It’s time as a fact of just destroying the fact and then recreating a fact. I mean vanitas is not always just vanitas, because vanitas also means a new thing. It’s kind of just destructive and productive processes.

For me, the term time is so difficult because it’s something we have a very fixed imagination about what it could be. We don’t know… that’s the big problem, but we have something we feel. I mean we are getting older so we have a very personal relationship to time but I think there is a bigger thing. I think it’s something much bigger than this little slice that we can feel and try to experience and think about but for me, all the world’s reality is just like a ‘happening’ in time. It is just like an extended meeting of matter and not just an object but subjects also.

Erin: … just a coordinate on the space-time continuum.

Alicja: I love the idea also that matter is never getting lost- even each dramatic way in which every atom of your body will still be there even if you are not there anymore. It is like my objects, in a way- a permanent recycling of eternal recurrence. It’s the very beginning of whatever it was giving itself back to us.

Erin: You recreate the big bang on a small scale.

Alicja: Not really at the moment, but I try to think how it could have been, or what that is, and what the big bang created and what this matter is and how it is shaped and who is naming it, and who is doing something to it and why it is what it is.

Erin: These tools in the exhibition such as compass points and clock hands- they speak to me of direction.

Alicja: It’s both direction as well as a tool of measurement. It’s basically measuring things and what we do to this reality is try to measure things to cut it into slices to create this system out of it to build onto the system. We need the system, but those two works are very much connected. However, the clock arms are just a pattern that already exists. I just took the clock arms out from the position it usually is not shown in because it’s just the position of the clock- the letters we use to count and describe time. I just moved them, not only in positions seen from a zero point as in our clock but I also moved them so I created a measurement system with time. This pattern then appeared which I discovered by chance and loved very much because it both behaves like light waves in this waveform which is kind of the essence of the universe, right? And that is kind of appearing in what we invented, but probably didn’t, so… we don’t know really.

For me, it’s a measurement system, something you try to orient yourself to that points to our position that is placed on the very first image. It’s not an image but a first illustration we are having of our universe. In 2015, they proved that gravitational waves exist by making the first observation of them. That is the first thing we know about this universe and a thousand of these measurements are creating this movement so you can see through this illustration and it is through this calculation and this illustration that it was moving. It was expanding and I recreated exactly this movement of what they illustrate as the first image of the universe with these compass needles.

Erin: Isn’t it weird that it was only now that they discovered a visual for this?

Alicja: But it’s just so abstract, right? I also think it’s a strange thing that even in science we always have this deep wish to illustrate things. We have to illustrate the image to create an image of what it could be so we always try to create pictures and that is for me, a very emotional picture because we don’t know exactly. But definitely it is existing and we can measure it and it’s very close together with the object pieces because that is the first idea of matter. Something started, like gravity started and then measuring appeared in space; that is kind of the breeze of creation.

Erin: Do you think about using the other senses to perceive time? The way that we measure the world, like the ways that you have shown, are all so visual. Do you ever think about other senses?

Alicja: I use quite a lot of sound elements also. Of course, I still think that we are very much visual. It’s probably our most important sense. It’s a very visual thing, science, so for me, it’s the most direct thing to use. But it’s of course not the only thing and, of course, I’m interested in other things. You know the first sound of the universe they discovered in 1974, all this background noise. I did a lot of pieces where I tried to catch the sound of energy; the sound of light, which is not light. You don’t catch the sound of light, but you can catch the vibration of the waves. I also try to use that. Also, very simply I sometimes try to include just counting sound in my exhibitions, which is not necessarily a clock like we think of a clock ticking. It’s something further that goes counting and that is creating a very emotional kind of feeling because it is like reacting.

Erin: Someone earlier was telling me about your exhibition at Whitechapel and how you have a mobile of mobile phones. I feel like you’re really good at just pulling from everyday life and then pulling at these huge questions and making them very palatable.

Alicja: It’s true, but it’s just things I’m using. I was always using lamps and clocks in my previous work and at some point, I started to destroy them and then with the phones it’s kind of the same habit. Then, I started using this app called SkyGuide where you use GPS systems to map the stars. When I think about that for a moment it’s kind of crazy- I mean Swedish satellites point you out and they create a picture and you are having that in your hand, in your palm, but that‘s a picture made by so many pictures from so many satellites. But then these things are not existing anymore and we just create a picture again and we try to figure out our position towards this picture and so it’s just things that are confusing, yet normal. When you think about these satellites that take care to correct your measurements towards because time is expanding so when you think about all this… everything gets really crazy.

Erin: Have you ever read about ‘Deep Time’? It is mostly used in geological terms, as in the deep time of the earth- putting things that are happening on the earth on the largest scale possible and just considering things from that point of view.

Alicja: That is a little bit of what I try to do with these objects. They’re coming from a much older stretch of what we have, which is elements.

Erin: Do you find it important that our sense of linear time is distorted?

Alicja: I don’t believe in linear time at all. I think it’s still a very human thing to try to get a system out of that- to divide it with poise and distance and make it livable. We are animals, so we need a system, something to be able to connect with each other and to make things happen. Of course, I think it’s interesting because it’s such a deep, philosophical question. I mean that is a question like ‘Is reality existing at all?’ or ‘Do systems really exist?’ These are questions that really drive me because I don’t know and we don’t know, but I’m very interested because that is the biggest question of our existence: how and why.

Erin: Any last words on the exhibition?

Alicja: To kind of sum it up, for me, it’s something else about language, which is not visible so much in the first moment. You see this object and it’s obviously a vase but it is called lamp. It’s kind of a Magritte thing, a trick, let’s say. It’s very much about that because language is so deep in our sense of reality also, so it creates strange shifts. But it is still a lamp, but can it also be a vase? It’s a simple thing- very relatable. The exhibition has so much to do for me with language and the expression of things.

There’s this whole theory that is deeply true that is that we don’t even develop feelings that we don’t have the term for. I had a funny experience when I was a kid when we went from Poland to Germany. I went with the German kids to a camp and they were super sad and saying they were homesick in German. We don’t have this term in Polish; it’s just simply not existing. I was not understanding what was wrong with them. It was a totally foreign feeling to me. So when you don’t have the term for it, you kind of just don’t have it at all because we create our world around these expressions.

Erin: It’s like, you know what you know, but you don’t know what you don’t know.

Alicja: And you can’t feel what you can’t express- what you can’t tell somebody about.

Erin Honeycutt

Photographs: artzine

Fra LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC, REYKJAVIK FESTIVAL. Ljósmynd: Lilja Baldursdóttir.

Fra LOS ANGELES PHILHARMONIC, REYKJAVIK FESTIVAL. Ljósmynd: Lilja Baldursdóttir.

Photos: & Other Stories.

Photos: & Other Stories.